The Right Amount of Wokeness

Don’t miss the sequel to this post: “Getting the Best from Wokeness by Having the Right Mean, Reducing the Variance and Mitigating the Losses from Extreme Values.”

Lance Morrow, in his August 2, 2020 Wall Street Journal op-ed “Dawn of the Woke,” and Andrew Michta, in his July 31, 2020 Wall Street Journal op-ed “The Captive Mind and America’s Resegregation,” mince no words about the dangers of too much wokeness.

Here is a sample of Lance Morrow (bullets added to distinguish different passages):

… cancel culture … is the 21st century’s equivalent of McCarthy’s marauding. The country’s myriad cancelers emit the odor not of sanctity but of sanctimony, and of something more ominous: the whiff of a society decomposing.

The indignant woke, who imagine themselves to be righteously awake and laying the foundations for a more just and humane world, ought to pause—to draw back for a moment, and consider the possibility that they are, as it were, fast asleep, caught up in strange, agitated dreams: that they have become a mass joined in a cult of self-righteousness, moral vanity and privilege. One of these days, they will have to be deprogrammed and led back to the real world. Woke institutions will need to be fumigated.

McCarthyism and the cancel culture—which is the military wing of wokeness—are most alike in their power to conjure fear. It was fear that kept McCarthy up and running for several years, and it is fear—of losing a job, losing an assistant professorship, losing one’s good name, one’s friends, fear of saying the wrong thing and bringing down ruin on one’s head, fear not to sign a party-line faculty petition—that fortifies and sustains the cancelers.

The woke, like hyenas, hunt in packs, and those in authority are craven.

Wokeness will prove harder to kill than McCarthyism. McCarthy was a B-movie monster. Wokeness is a zombie apocalypse.

And here is a sample of what Andrew Michta writes:

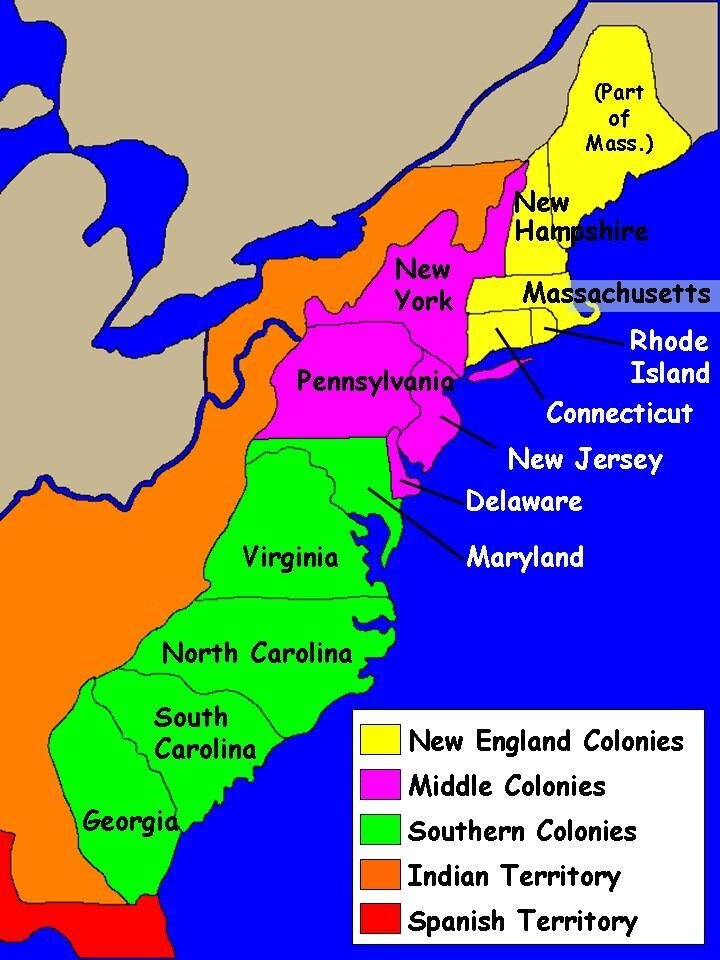

The ill-named progressivism that has inspired shrill demands to dismantle police forces and destroy statues is only a small manifestation of a massive project aimed at the re-education of the American population. The goal of this project is to negate the story of the American republic and replace it with a tale anchored exclusively in race categories and narratives of oppression. The nature of this exercise, with its sledgehammer rhetoric that obliterates complexities in favor of one-dimensional “correct” interpretations, is as close to Marxist agitprop as one can get.

… radicals destroying monuments and issuing wholesale denunciations of America’s past are wreaking destruction on ordinary Americans and their history, not on the elites and their ideology. Today’s elites as a rule do not believe they have any obligation to serve the public, only to rule it, and so they express little or no disapproval of college students toppling statues on federal land or looters raiding supermarkets. To criticize them would open elites to the charges of “populism” and “racism.”

The current radical trends carry the seeds of violence unseen in the U.S. since the Civil War. The activists ascendant in American cities insist on the dominance of their ideological precepts, brooking no alternative. Such absolutism forces Americans away from the realm of political compromise into one of unrelenting axiology, with one side claiming a monopoly on virtue and decency while the other is expected to accept its status as perpetually evil, and thus assume a permanent penitent stance for all its real and imagined misdeeds across history.

The U.S. is roiled by spasms of violence and intolerance today because government at all levels—public education systems, states that allow universities to promulgate speech codes and “safe spaces,” court decisions that define constitutionally protected speech as, in effect, everything but political speech …

ideologues have nearly succeeded in remaking our politics and culture; they are reinforced by a media in thrall to groupthink, by credentialed bureaucrats, and by politicians shaped in the monochrome factories of intellectual uniformity that are America’s institutions of higher learning.

At a minimum, I have sympathy for concerns that too much wokeness might hurt freedom of speech, which I care deeply about, as you can see from all the posts flagged in “John Stuart Mill's Brief for Freedom of Speech.” So, at least for the sake of argument, let’s concede that too much wokeness can cause bad things to happen. What does that say about how much wokeness we should wish to have on average in society?

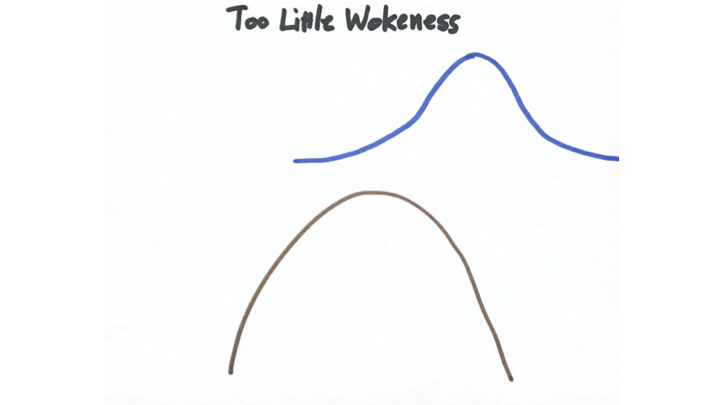

We can do some simple analysis. Take a look at the following figures, which I will explain. To match our usual left-right political conventions, I draw greater wokeness as being further to the left.

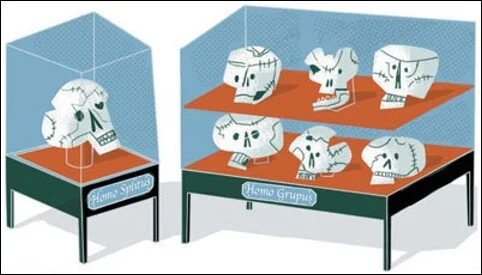

A key assumption I will make is that, whatever the average level of wokeness in society, there will be people with higher and lower levels of wokeness. For simplicity, I’ll model this as a normal distribution, which seems pretty reasonable since it might well be that many approximately additive forces (additive for an OK metric of wokeness) contribute to one’s level of wokeness.

The probability distribution of wokeness interacts with a loss function that shows how losses are generated from a wide variety of situations impacted by differing levels of wokeness. (I will draw the loss function upside-down so higher values are better.) One can and should argue about the shape of the loss function, but to make my point, let me assume it is symmetric. If a normal distribution interacts with a symmetric loss function, then we should wish that the mean (average) level of wokeness be right at minimum of the loss function—the top of the hill as I draw it above.

What would it look like in our world if the mean of the normal distribution of wokeness were at the minimum of the loss function? There is a simple answer: the horrors from too much wokeness would be as great as the horrors from too little wokeness. I don’t think we are there yet. Anyone who has been paying attention lately and tried to get a historical perspective should realize that the horrors from too little wokeness are still truly awful. The horrors from too much wokeness are still not at the same level. So from where we are now, increasing the average level of wokeness (while retaining the same standard deviation of the normal distribution) would be a good thing. It will cause some horrible things to happen from the highest extremes of wokeness, but it will prevent many other horrible things from happening from the lowest extremes of wokeness.