Logarithms and Cost-Benefit Analysis Applied to the Coronavirus Pandemic

Two key tools for economics are coming up in the context of the coronavirus pandemic: logarithms and cost-benefit analysis. As for logarithms, the Financial Times has been producing graphs such as the one above. The vertical axis is logarithmic: that is, every time the number of new cases in a week goes up by a factor of ten, the increase in height shown is the same. The horizontal axis is in days since the first time a country had 200 cases in one week. Given the logarithmic vertical scale and the horizontal scale in days, the slope of each country’s curve shows the growth rate of the number of new cases.

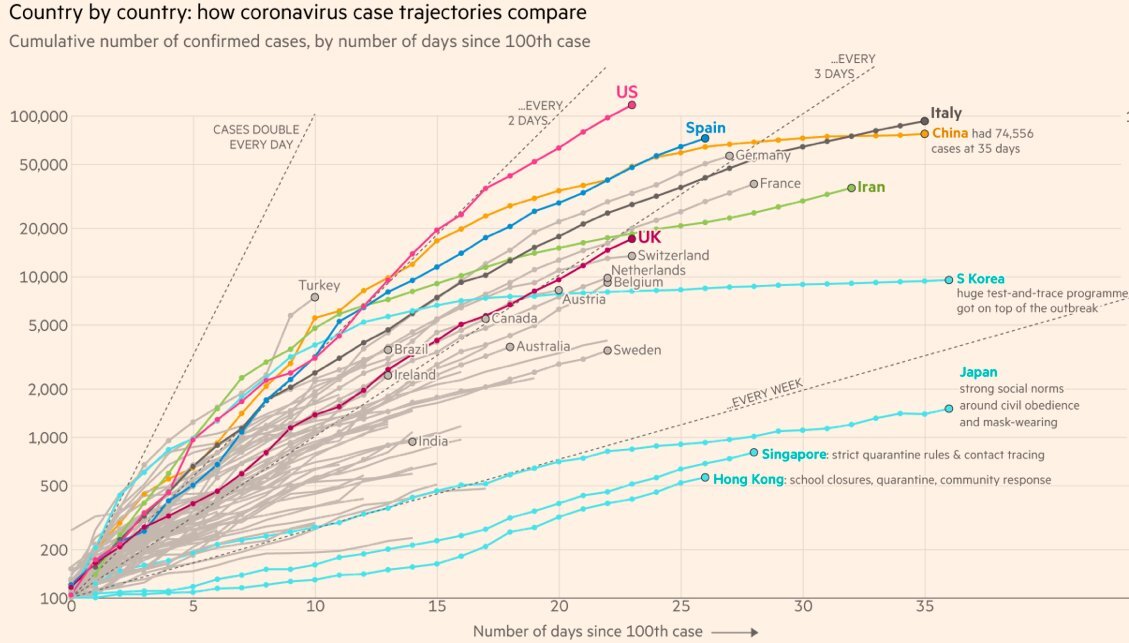

In addition to the graph above of the number of new cases in a week, the Financial Times also creates graphs showing on a logarithmic scale the cumulative total number of cases for each country. The graph below helpfully shows the slope corresponding to the cumulative number of cases cases doubling every day, every two days, every three days and every week:

For more on logarithms, see my 2012 post “The Logarithmic Harmony of Percent Changes and Growth Rates.”

As for cost-benefit analysis, a key idea is to put a dollar value on a human life. We don’t know who, but we know some additional people will die if we don’t shut down big sectors of our economy that involve a dangerously high level of physical human proximity, such as schools and restaurants for dine-in. Someone dying or someone living is called a “statistical life.” Suppose for example that almost everyone ultimately gets the coronavirus and that allowing the number of cases to grow too fast would lead to a shortage of hospital beds that would make .6% of everyone in the US die instead of .3% of everyone in the US dying if we can slow things down enough to give high-quality treatment to everyone who has a serious case of COVID-19. Given the 327.2 million population of the US, that means shutting down big sectors of economy for a while would save almost a million lives. It is a million statistical lives, since we don’t know exactly who it will be, but that would be a lot of real people.

I used $9 million as the value of a statistical life in “Cost Benefit Analysis Applied to Neti Pot Use,” But Cass Sunstein, in the article shown below, says the current value is $10 million per statistical life.

Under both Republican and Democratic administrations, regulatory agencies have relied on a monetary figure to capture “the value of a statistical life.” It is now around $10 million. Monetizing human life seems cold-hearted; our intuition rebels against it. But it’s essential.

Why can’t we say a human life is more valuable than that? Here is one simple calculation that illustrates why not. At $10 million per statistical life, the lives of everyone in the 327 million US population are worth $3.272 quadrillion = 3,272,000,000,000,000. It would take more than 152 years of 2019’s US GDP to add up to that much. (2019 US GDP was $21.427 trillion.) So we don’t really have even $10 million to spend saving each person’s life. To pay $10 million to save a statistical life, we have to pool money from quite a few people to pay for each life saved.

Here is how Cass Sunstein makes the case:

You can ask a lot of questions about that research. But it’s clear that in choosing whether to proceed with lifesaving regulations, or how aggressively to proceed, agencies will be required, if only implicitly, to assign some monetary figure to risks of death. In deciding how to handle risks in the workplace, or risks from air pollution, regulators cannot avoid the existence of trade-offs. They aren’t going to spend billions of dollars to prevent one or two deaths, or even 10 or 20.

…

If you take too many precautions against risks — for example, by banning automobiles — you are going to create different risks. Expensive precautions, by virtue of their expense, can endanger human beings — among other things, by increasing poverty and unemployment, which would mean more death. If we care about human welfare, we will insist on exploring the costs and benefits of various approaches, because the resulting numbers give us indispensable information.

But now turn back to the case of the coronavirus pandemic with a simple back-of-the-envelope calculation. A million statistical lives saved (from reducing the death probability per person by .3%) at $10 million each, multiplies out to $10 trillion. That is a bit less than half a year’s worth of GDP. And no one is talking about totally shutting down the economy. If the economy were shut down about halfway, which is a lot more restrictive than what we are doing now, it takes a whole year of being halfway shut down to equal $10 trillion. So if we can do the trick with less cost than that, it is worth it.

There are some subtleties I should address. First, what if low-income folks are paying most of the economic cost of the induced economic coma? Then, if they are not compensated, the dollars they are losing aren’t just any dollars, they are the precious dollars of those who are struggling financially. (See “Inequality Aversion Utility Functions: Would $1000 Mean More to a Poorer Family than $4000 to One Twice as Rich?”) But we can compensate those who are losing their jobs and as a consequence being thrown into a financial crisis. And we have so far gone some fraction of the way in that direction.

Second, what if most of the lives saved would be older folks who didn’t have many years left anyway? Under one calculation, that cut the benefit in half; Cass Sunstein writes:

… Michael Greenstone and Vishan Nigam of the University of Chicago analyzed the likely benefits of “a moderate form of social distancing,” including a seven-day isolation for anyone showing coronavirus symptoms, a 14-day voluntary quarantine for their entire household and dramatically reduced social contact for all those over 70 years of age. They found that over a period of seven months, the result would be to prevent 1.7 million deaths. Under standard assumptions, that’s $17 trillion in benefits. Because a significant percentage of the avoided mortalities involve older people, Greenstone and Nigam adjusted the number down — but still, it’s over $8 trillion, which is the equivalent of $60,000 per U.S. household.

Some people object to the idea that the life of someone older might be worth less, but when it is family, I think almost all of us would be more comfortable with a grandfather or grandmother volunteering to give his life to save the life of a grandchild than a grandchild volunteering to give their life to save the life of a grandfather or grandmother. But let me continue to keep my arithmetic simple by treating any statistical life as worth $10 million.

The bottom line is that it is worth a lot to save a million lives. So it is worth doing a lot to save a million lives. Almost any anti-COVID-19 measure being contemplated is worth it according to standard cost-benefit calculations if it can save a million lives.

It is possible that after learning more about the coronavirus, we would determine that strict social distancing would only save 200,000 lives (or perhaps the equivalent of 200,000 young lives after adjusting for the actual mix of ages of the lives saved). Then the cost benefit calculation would still say it was worth shutting down half the economy for 9 weeks or so, but perhaps not for more than that. But we haven’t overdone social-distancing and educational and business closures yet, even if the trouble we are taking in that regard can only save 200,000 lives.

Update, April 1, 2020: Don’t miss Aatish Bhatia’s graphs with log cumulative cases on one axis and log new cases on the other and time shown dynamically.

Don’t miss these related posts: