"Marvin Goodfriend on Electronic Money" in Japanese: Marvin Goodfriendの電子マネーに関して →

The link above is to the post in Japanese, translated by Makoto Shimizu. The English version can be found here.

A Partisan Nonpartisan Blog: Cutting Through Confusion Since 2012

The link above is to the post in Japanese, translated by Makoto Shimizu. The English version can be found here.

I owe a debt of gratitude to Makoto Shimizu, who continues to translate key posts into Japanese. The link above is to the post in Japanese. “On the Need for Large Movements in Interest Rates to Stabilize the Economy with Monetary Policy” in English can be found here.

“Behold my son, with how little wisdom the world is governed.”

– Axel Oxenstierna, Swedish statemen who lived 1583 – 1654, via Matt Miller’s book The Tyranny of Dead Ideas, p. 228, who offers this interpretation: “In one sense, the Swede was simply saying, ‘Look at what idiots are running things!’ In another sense, though, he was offering a deeper observation about how small a quantity of wise governance is actually required to keep the human enterprise on track.

Here is a link to my 55th column on Quartz: “Righting Rogoff on Japan’s monetary policy.”

This column is meant to back up my tweet:

Ken Rogoff is wrong when he says the BOJ’s Kuroda has done “whatever it takes” monetary policy for Japan: http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/japan-slow-economic-growth-by-kenneth-rogoff-2014-12…

One other note: Ken sent a nice reply to the email I sent him about my work on eliminating the zero lower bound, soon after I sent it.

Update December 19, 2014: Although the main point of my column is to emphasize the importance of putting negative paper currency interest rates in the monetary policy toolkit now rather than a decade or two from now (with particular urgency for the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan), I know that for many readers, the reprise of the Spring 2013 media furor about Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff’s work is equally salient. Personally, I believe eliminating the zero lower bound is much more important as whether debt lowers economic growth even when it doesn’t cause a debt crisis, but the issue of debt and growth does need to be addressed as well.

I had a chance to read Ken Rogoff’s and October 2013 FAQ http://scholar.harvard.edu/rogoff/publications/faq-herndon-ash-and-pollins-critique. Substantively, I think this is a good response to the Thomas Herndon, Michael Ash and Robert Pollin paper (linked there) that started the media furor in Spring 2013. But my own substantive concerns are not those. They are the concerns that Yichuan Wang and I detail in our two Quartz columns and two other posts on Reinhart and Rogoff’s work:

In my view, these posts by Yichuan Wang and me are a good example of how, in Clay Christensen’s terms, the disruptive innovation of the economics blogosphere is beginning to move upscale and challenge traditional economics outlets such as working papers and journal articles.

I hope that, taken as a whole, what I write on my blog puts things in the context of the literature, and–through links–gives the kinds of references that are rightly considered important for academic work. In any case, for me the major source of the not inconsiderable number of references I have had in my academically published work come from other people telling me about work related to my own. The same thing happens online. I deeply appreciate the many links people send me in tweets and in more private communications.

Although it is natural for an individual blog post to be be much less complete than a working paper or journal article, I hope to achieve a reasonable balance between breadth and depth in this blog as a whole. And of course, the relative difficulty of putting mathematical equations in Tumblr means I will choose the working paper format once the number of equations needed to make a point exceeds a certain threshold.

To repeat, although Thomas Herndon, Michael Ash and Robert Pollin’s paper definitely piqued my interest and Yichuan’s interest and so led to our analysis of Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff’s postwar data, I am critical of the substance of Carmen and Ken’s work based on my work with Yichuan, not based on the work of Thomas Herndon, Michael Ash and Robert Pollin.

In relation to our own critique of Carmen and Ken’s work, let me make three substantive points:

Did Carmen and Ken overstate their case?

While I feel confident that Yichuan’s and my substantive critique has not been adequately addressed, I am much less confident about claims I made in

“Righting Rogoff on Japan’s monetary policy”

about how policy-makers interpreted Carmen and Ken’s work (and how they could have been expected to have interpreted it, given what was written).

Ken’s FAQ document points to the 2010 Voxeu article “Debt and Growth Revisited” as something that could have provided more balance to policy makers in interpreting Carmen (and Vincent) and Ken’s work. Because policymakers might be more likely to read a Voxeu article than an academic paper, this Voxeu piece is an important touchstone for whether Carmen and Ken overstated the strength of the empirical evidence in favor of the idea that high public debt slows down growth in the range that was relevant to policy in the last few years.

The issue I have with the Voxeu article “Debt and Growth Revisited” is that it never mentions the fact that the normal standard of establishing causality in economics is to find a good instrument, or some other source of exogeneity or quasi-exogeneity. In other words, the inherent difficulty of establishing causality in this kind of data is never mentioned. Here is how strongly Carmen and Ken suggest in their Voxeu article “Debt and Growth Revisited” that there is causal evidence despite the highly endogenous nature of the data:

Debt-to-growth: A unilateral causal pattern from growth to debt, however, does not accord with the evidence. Public debt surges are associated with a higher incidence of debt crises.9 This temporal pattern is analysed in Reinhart and Rogoff (2010b) and in the accompanying country-by-country analyses cited therein. In the current context, even a cursory reading of the recent turmoil in Greece and other European countries can be importantly traced to the adverse impacts of high levels of government debt (or potentially guaranteed debt) on county risk and economic outcomes. At a very basic level, a high public debt burden implies higher future taxes (inflation is also a tax) or lower future government spending, if the government is expected to repay its debts.

There is scant evidence to suggest that high debt has little impact on growth. Kumar and Woo (2010) highlight in their cross-country findings that debt levels have negative consequences for subsequent growth, even after controlling for other standard determinants in growth equations. For emerging markets, an older literature on the debt overhang of the 1980s frequently addresses this theme. …

… We have presented evidence – in a multi-country sample spanning about two centuries – suggesting that high levels of debt dampen growth.

I appreciate the note of uncertainty in the sentence

Perhaps soaring US debt levels will not prove to be a drag on growth in the decades to come.

But I feel that for the typical policy maker reading the Voxeu article, this note of uncertainty is largely cancelled out by the next sentence:

However, if history is any guide, that is a risky proposition and over-reliance on US exceptionalism may only prove to be one more example of the “This Time is Different” syndrome.

The phrase “if history is any guide” phrase in particular suggests that the historical evidence gives some clear guidance, and the sentence as a whole points to an interpretation of “Perhaps soaring US debt levels will not prove a drag on growth in the decades to come” as simply making a bow toward random variation around a regression line rather than expressing any uncertainty about what the causal regression line for the effect of debt on growth says before other random factors are added in.

In any case, saying “Perhaps soaring US debt levels will not prove to be a drag on growth in the decades to come” is not the same as if Carmen and Ken had said

Of course further research could overturn the suggestion we find in the evidence that high debt lowers growth, and there are always many difficulties with interpreting historical evidence of this kind.

Of course, there is always the possibility that Carmen and Ken said almost exactly that, in a forum that most policy makers would have noticed, but one that Idid not notice. (My own reading is ridiculously far from comprehensive.) If so, I would love to get a link to it. Ideally, I would like to see the main text of Ken's FAQ document collect in its main text all the details (including of course venue or outlet and date) about all the strongest caveats and cautions against overreading that Carmen, Vincent and Ken wrote about their work.

One extremely important note that the FAQ document does have is this quotation from Reinhart, Reinhart, and Rogoff (2012), “Public Debt Overhangs: Advanced-Economy Episodes since 1800.” (Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26(3)):

This paper should not be interpreted as a manifesto for rapid public debt deleveraging exclusively via fiscal austerity in an environment of high unemployment. Our review of historical experience also highlights that, apart from outcomes of full or selective default on public debt, there are other strategies to address public debt overhang, including debt restructuring and a plethora of debt conversions (voluntary and otherwise). The pathway to containing and reducing public debt will require a change that is sustained over the middle and the long term. However, the evidence, as we read it, casts doubt on the view that soaring government debt does not matter when markets (and official players, notably central banks) seem willing to absorb it at low interest rates – as is the case for now.”

This suggests to me that Paul Krugman went overboard in his criticism of Carmen and Ken–at least before he backed off somewhat. I am not up on all the details, but it is my understanding that some of Paul Krugman’s stronger criticisms against Carmen and Ken in terms of providing intellectual backing for austerity might have been better leveled against other influential economists, such as Alberto Alesina. But I would need a lot of help to know whether such criticisms were even appropriate for other influential economists such as Alberto. For the record, the current Wikipedia article on Alberto Alesina says:

In October 2009 Alesina and Silvia Ardagna published Large Changes in Fiscal Policy: Taxes Versus Spending,[3] a much-cited academic paper aimed at showing that fiscal austerity measures did not hurt economies, and actually helped their recovery. In 2010 the paper Growth in a Time of Debt by Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff) was published and widely accepted, setting the stage for the wave of fiscal austerity that swept Europe during the Great Recession. In April 2013 some analysts at the IMF and the Roosevelt Institute found the Reinhart-Rogoff paper flawed. On June 6, 2013 U.S. economist and 2008 Nobel laureatePaul Krugman published How the Case for Austerity Has Crumbled[4] in The New York Review of Books, noting how influential these articles have been with policymakers, describing the paper by the ‘Bocconi Boys’ Alesina and Ardagna (from the name of their Italian alma mater) as “a full frontal assault on the Keynesian proposition that cutting spending in a weak economy produces further weakness”, arguing the reverse.

Thus, Wikipedia conflates Carmen and Ken’s views with those of Alberto Alesina and Silvia Ardagna.

But just as Carmen and Ken’s views should not be conflated with Alberto and Silvia’s views, neither should my views be conflated with Paul Krugman’s. Soon after Thomas Herndon, Michael Ash and Robert Pollin’s paper came out, I wrote in Quartz:

Unlike what many politicians would do in similar circumstances, Reinhart and Rogoff have been forthright in admitting their errors. (See Chris Cook’s Financial Times post, “Reinhart and Rogoff Recrunch the Numbers.”) They also used their response to put forward their best argument that correcting the errors does not change their bottom line. Given the number of bloggers arguing the opposite case—that Reinhart and Rogoff’s bottom line has been destroyed—it is actually helpful for them to make their case in what has become an adversarial situation, despite their self-justifying motivation for doing so. And though I see a self-justifying motivation, I find it credible that Reinhart and Rogoff’s original error did not arise from political motivations, since as they note in their response, of their two major claims—(1) debt hurts growth and (2) economic slumps typically last a long time after a financial crisis—the claim that debt hurts growth is congenial to Republicans, while the claim that it is normal for slumps to last a long time after a financial crisis is congenial to Democrats.

The results from the fairly straightforward data analysis that Yichuan and I did made me somewhat less sympathetic to Carmen and Ken. Nevertheless, I think they spoke and wrote in good faith. Errors of omission are a different issue, and there we all stand condemned, in a hundred different directions for each of us.

It is from the perspective that we all stand condemned for errors of omission of one type or another, that I hope my words in “Righting Rogoff on Japan’s monetary policy” are taken. I also urge you to distinguish carefully between simply reportingone side of the Spring 2013 debate about Reinhart and Rogoff’s work, and things I say on my own behalf: principally that Ken does not challenge policy-maker conventional wisdom as much as I would like to see.

Carmen and Ken literally did not have time enough to defend themselves adequately back in Spring 2013. Now that the dust has cleared, I would be glad to see them do more to tell their side of the story.

This update is my effort to make up for some of my own errors of omission when I wrote “Righting Rogoff on Japan’s monetary policy.” In particular, I thought wrestling with Ken’s FAQ document was the least I could do to give a little more voice to Carmen and Ken’s side of the story. (To the extent that you were persuaded by Thomas Herndon, Michael Ash and Robert Pollin’s paper, or were persuaded by unjustified accusations of bad faith on Carmen and Ken’s part, you should take a close look at that FAQ document.) As always for my columns, this update in the companion post will become part of the permanent record for this column 30 days or so after initial publication on Quartz, when I am contractually allowed to bring the column home to supplysideliberal.com.

I like this illustration I am reblogging from the smithsonian Tumblog. It is accompanied by this note:

Astronomers at Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics find new “mega-Earth”.

“This is the Godzilla of Earths!” - CfA researcher Dimitar Sasselov, director of the Harvard Origins of Life initiative"

Read more at Smithsonian Science.

Like reblogged posts from econlolcats, this post is also intended as a harbinger of a Quartz column I expect to appear today: my response to Ken Rogoff's Project Syndicate opinion piece “Can Japan Reboot? The working title is "Righting Rogoff on Japan’s Monetary Policy."

John Erdevig is a good friend of mine, a lawyer, a Unitarian Universalist, and an environmental activist. This guest post gives his thoughts about religion, science and environmental activism. There is a depth to his thinking that I admire. See what you think.

Let me begin by talking about Michael Dowd, who came to speak to our Unitarian-Universalist congregation. Dowd, for those of you unfamiliar with his bio, was raised Roman Catholic, ordained United Church of Christ (congregational), and later married a Unitarian who is my favorite science-and-religion author, Connie Barlow. I term Dowd a revisionist deist, as can be deduced from this book title, “Thank God for Evolution!” This is key: He weds the speaking style of an informed environmental activist with the extemporizing and inspiration of an old-school preacher walking the stage. He quotes cosmologist Carl Sagan and especially in front of non-UU audiences, updates the most relevant parts of the Hebrew Bible for believers. He is re-telling an ancient story, a sacred story. Why and what would it have to do with us?

His visit kindled a discussion among my friends. One flavor of our response to an impassioned environmentalist like Dowd… even Sagan… is, “Why do we need an emotional message?” Let me paraphrase the critique more explicitly: “We need science teachers. We need sound, tested, science-based technique e.g. when it comes to lowering emissions. Engineers and economists with cool heads and painstaking methods might not get too excited about communing with nature. We need well-thought-out economic policy, and that takes time. If we are going to the public at all, then we need to educate the public in the science, and in the currently-best technology, and in the good public policy options.”

I get it. My own intensity, my exploration of how to heighten the sense of urgency among my fellow citizens, doesn’t necessarily help the development of best technology and practices. Dowd and my favorite poets and essayists don’t necessarily inform the public debate about where the biggest “bang for the taxpayer buck” is. “Urgency” itself is insufficient, and sometimes harmful in the tool-making and decision-making process.

Any talk about moving a democracy and a consumer economy to adopt alternative technology and pass a carbon tax, say, inevitably turns to politics. Much is at stake with the politics of climate stabilization… to lose this political struggle is unthinkable to me. Now, politics runs in large part on emotion and identity, which I sum up in the questions, “How do you feel, and what’s your story?”

All advocates of reform need to keep our heads screwed on straight and encourage others not to flip out. But we need to understand that masses of voters and consumers –and we, admit it or not – are also moved by values and simplified, value-laden messages. Great change, especially under urgent circumstances, involves human head and heart, sometimes weighing in favor of one or the other.

When publishing emissions rules in the Code of Federal Regulations, head prevails. It starts with a statute and gets worked out in the lab. I would argue that when passing the enabling federal legislation, e.g. Clean Air Act, a quite sensible statute, heart prevailed. It was passed during a period of compassionate reform and counter-cultural ferment that took the slow deliberation of mainstream politics by storm. The politics of technical regulation promulgation is different from the politics of reform legislation. Preferably, regulation regularly transcends politics and focuses on data and optimizing sound objective functions

In the sphere of economic policy, Miles has argued in discussions with me that a carbon tax does much of the motivational heavy-lifting, while acknowledging that good old fashioned rhetoric helps passage of such a tax. The tax works mainly through market forces, which takes care of day-to-day motivations. Manufacturers and consumers weigh prices and reduce carbon, without a lot of hoopla and transcendent values. Miles also uses the language of political activism, which is of necessity simpler and more emotional than economics and emissions tech: “Demonize coal.” It is a means to an end. (Though I would argue that, in my value system and penchant for metaphor, coal is a fallen soul, perhaps a fallen angel, a human character, therefore a somewhat sympathetic character, but still deserving of a public ostracizing. It was once a miracle to humanity, a boon of artificial energy for masses once condemned to the more brutish manual labor and low standards of living. Just try not to use electricity from your nearest coal-fired plant for a week, and see if you don’t get cranky. Yet now it is a substance so harmful and out of control that I might call it a demon, if it weren’t for the fact that it takes our internal, worse angels – a veritable gluttony for cheap electricity – to make Demon Coal so demonic. We exorcise our failings in demonizing external things, and it might as well be mountain-removing coal.)

With such a nifty economic tool as a revenue-neutral carbon tax, possibly with some appeal to small-government fans, do we need the kind of mytho-poesis that Michael Dowd engages in? Here is a slippery slope: Do we need to get bogged down in whether any Christian or post-Christian concept of compassion and justice can be philosophically extended into the natural world? Chuck out Dowd and Sagan for a minute. Does the Earth need “saving?” or does it endure in indifference to any one species? What they regard as a sacred “right relationship” between Humanity and Nature… well, it boils down to survival of a few generations of our fallible and inevitably doomed species… so human-centric. There are intellectual problems to work out. So ok, let’s also leave aside the adjective “sacred” for now. So, let’s not capitalize Humanity and Nature as if they were singularities we can simply sum up and relate to one another.

On the other hand, I’m not sure that discussions of conservation, renewables and tax policy can bypass the psychology of great reform movements in this country. There, metaphor, simplified messages and religion have weighed in heavily: abolition, women’s vote, civil rights—and I would add in environmental legislation. Sure, there is something practical about the Clean Water and Clean Air Act. Air and water pollution was so bad in the 1970’s that legislation passed over Richard Nixon’s veto. Many saw it as a no-brainer. In my boyhood in the early 1960’s, the Milwaukee River was like the Cuyahoga, Cleveland’s “Burning River.” The black soot stuck in my nose after a trip to downtown Milwaukee. Even privileged people couldn’t escape the ugliness, stench and coughing. The U.S. has a political tradition of conservation going back to Teddy Roosevelt and that tradition is as much informed by romanticism – think charismatic megafauna like bison, and rugged outdoorsmen in wide open spaces – as by the calculus that if you chop all the trees down, a virgin forest cannot be restored and bad things happen downstream.

So don’t forget Joni Mitchell’s “They Paved Paradise” and don’t forget Earth Day. And it went beyond hippies and flower children, the children of nature. There was a revival of earth-centered Native American and Celtic spirituality. This spirituality was repeatedly reinterpreted by a rising New Age movement—a movement that was adopted even by the upper classes. Before the organized and well-funded reaction of the 1980’s, when Reagan triumphed and turned back much, but not all, of this far-reaching reform with the whole false dichotomy of economy versus ecology, jobs versus the environment, there was urgency, poetry, and inspiration. It takes all kinds to make an environmental movement. People willing to fill out Environmental Impact Statements, and people to march and sing. Happily, it perhaps didn’t take as much marching and singing, and nothing like a Civil War, to accomplish significant reform by getting landmark environmental legislation passed.

Let me illustrate both the need and danger for emotionally motivated allies in a challenging way. Have you ever felt embarrassed when a reporter wades into a demonstration whose goal you basically agree with, such as slowing climate change, and the reporter shoves a microphone in front of a sign-carrying participant, and asks something like, “So why are you here and want do you want?” And the participant is remarkably uninformed and says something like “we want to save the ozone.” Now, some greenhouse gases also harm the ozone layer. But the ozone layer is actually on the mend ever since the banning of chlorofluorocarbons. We’re trying to limit carbon dioxide and methane emissions to stabilize the climate. What to specially educated folks is a simple distinction is not so simple to many voters and allies. In this, I am not condescending. That participant can certainly absorb more science and policy. For whatever reason they haven’t yet, and maybe that’s on us. I can think of a lot of reasons they haven’t, which might not reflect well on their intellect or citizenship, but I don’t know that they are weaker in those categories compared to me. I do know this: We need that person to show up at demonstrations, and we need that person to vote. They would be even more useful allies if we could also get them to a class or a teach-in geared to whatever interest or education level they have. But the matter is urgent enough, that we need Creation-care Christians, and New Age folks who don’t know ozone from shinola, to join with temporary allies and opportunists (the gas drillers for now?), and then join with us. I’m maybe talking about the technocratic-minded and compassionate-enough who see the writing on the wall and personalize it as the writing on the wall for their existence and moral credibility (as at Belshazzar’s feast) and the existence of our children. I’m talking about people “whose heart is in the right place.” Reform politics is about both informing and moving people toward policy. The law once passed and in the implementation phase then doesn’t require quite as much mass education or altruism to sustain itself. But first, you have to get the enabling legislation passed. If you can get some non-legislative progress, e.g. people to pay a bit more, initially, for LEDs, and use less electricity in their home, so much the better. But mainly it is about legislation such as a carbon tax, or regulations inhibiting coal plants that need mass support, and not just demonstration projects (solar. hybrid and LED rebates) for first-adopters like me.

Mass support to effect reform legislation does not even require an electoral majority. It involves a motivated plurality, often just a little over a third. Nearly a third in opposition is tolerable. They can be surprised and rolled over briefly before they find an effective response and rebuild their coalition around some other issue that ascends in the voters’ consciousness more than climate change. To ride the very brief waves of change that lead to landmark legislation, you need to understand that there is another rough third of the populace that is indifferent on the issue, and they will mostly sit it out. You don’t want to annoy them, yet you must find language to motivate your one-third base.

So I would argue that even if you can’t relate to Dowd and Sagan, even if you shrink from divinizing, godifying (or demonizing) anything, religious rhetoric has a vital place in the movement–even if you don’t want to worship that way; even if you regard poetic metaphor as imprecise, too emotional, a revival of the kind of irrationality that got us into supernaturalism or wasteful technical experiments and ineffective policy. Perhaps denigration of poetry and God-talk is an argument meant to contain it by insisting that there should be more data and fewer metaphors in any public presentation. Perhaps that’s an argument that the world needs more scientists, technicians and academics – who insist on time, cool consideration and method – and fewer inspirational preachers and poets. I insist we need both. You have to see the political need for this aspect of rhetoric, at least. Dowd helps to fracture the right-wing coalition that previously counted on some large denominations to oppose environmental reform, to oppose science itself. Sagan brings along many atheists. Sagan and my guru, Connie Barlow, travel with the circle of scientists who are careful, have professional integrity, and use their prodigious frontal lobe, but nevertheless are touched deeply by curiosity—scientists who freely articulate a sense of awe at the phenomena they also coldly measure and interpret. Religious leaders share the stage now with scientists. To use imagery from neuroscience, like extreme altruists and expressive artists, their orbitofrontal cortex or amygdala lights up more on brain scans when they star-gaze or look at data on flood and drought trends.

That latter category would include me, except for the professional science or religious credentials or MFA – I’ll be leading considerably back from the charismatic pack. The project of keeping hand and heart in sync is intuitive, irresistible to me, and not just a political strategy. I get geeked about kilowatts and batteries, and how to put them to use to cut emissions in mowing. EPA data tells me that such landscaping activity contributes 1/5 of metropolitan area non-mobile source air pollution. To me, it is low-hanging fruit. Landscape activity happens to do other things for me. I find bliss in it, because there is an intersection between my personal joy and a human need. To keep my frontal lobe focused, I depend on the endorphin rush of outdoor physical exercise. Unlike law practice, where the product is ambiguous and day-to-day activities are a work-in-progress, I can look at a mown lawn and trail, with children are playing on the lawn and all ages hiking the trail, and get an immediate sense of accomplishment. Meanwhile, addressing the human need gives me a oxytocin dose, I’m sure. Hedonic and eudemonic happiness in one neat package. Most amateur gardeners or natural area preservationists would not long survive in a laboratory or academic setting where the actual and official historical “cure” to climate change will be “found.” We are however on another front line, or we articulate a different aspect of the united front. It has been called immersion or transcendent experience. Feeling, and then articulating a religious and poetic aspect to our experience of the more congenial sides of nature might be about hormones that influence emotion, and about group word-play and story-telling. Can this enthusiasm and imagery exaggerate and distract? Surely. But properly practiced, it puts what is important front and center and serves to properly focus emotional energy. It’s not like one can suppress or ignore enthusiasm. In general, our society’s emotional energies are poorly focused now, in relation to the existential and moral crisis of climate change.

There is a maxim attributed to the Iroquois or Seven Nations people: “In all council deliberations, we consider the effect of our decisions on The Seventh Generation.” Our best energies seem focused on the next quarter’s corporate profits, and how much money we’ve stuffed away for our retirement. The world and the generations, can take care of themselves, seems to be the dominant opinion, if the world and generations are mentioned at all. We were taught to believe in progress, in fact there has been astounding human progress, but it is now a long way to fall when we perceive a period of precipitous human and ecospheric degradation… polar environment gone, populous coasts underwater, oceans acidified and incapable of supporting a vast food chain base of calcium-excreting organisms. The dominant religious ideology of the West, post-Enlightenment, is that we are heir to a God that merely set the universe in motion. Or we are heir to a dead God. But we’d hoped for better. Humanists frequently fall back to the more realistic view that we cannot attain anything like god-like perfection. In the 21st century, we acknowledge the god-like aspect of our unprecedented control of the environment. With it there seems to come at least a heightened responsibility for more enlightened human self-preservation. It is all very depressing to see how we’ve botched the job, and the juggernaut of climate change will affect The Seventh Generation. (Are we “The Least Generation?”) Defining our success or failure aside, I find few total fatalists, and most in my circle look to soldering on. For me, that entails refocusing energies, dissenting from the dominant opinion, and challenging the impoverished, mass-suicidal emotional paradigm of individualism and infinite growth. But I would not start with religion; I would deliberately start with science, specifically natural history, on the way to religion in this reform. Connie Barlow suggests we must see humanity as also being in charge of its sacred narrative. We can witness and understand the universe, from a level our ancestors would’ve regarded as god-like. Barlow says, any religion of our time must be informed chiefly by natural science. To get up in the morning and face ourselves in the mirror without loathing, to face our finiteness without abject terror, and moreover, to do the right thing, we need religion, but not just any kind, obviously – the U.S. is already a uniquely church-attending society among developed nations. The conscious process of creating a narrative for religion (etymologically, “re-linking, re-binding”) is called mytho-poesis. Science must inform our sacred story. The cosmic and evolutionary epic, informed by natural history and that wonderful modeling of interdependence, ecology, is our sacred story. It is a story waiting for elaboration in your mind and in groups small and large.

As I sometimes deliberately think about my own death, in parallel I need to contemplate the full violence of actual world-endings. Because frankly various apocalypses are in the headlines and academic papers, if you connect the dots. And some are coming more into proximate view. I actually can’t say that we won’t live to see some of the worst that climate change has to offer, where enough storm surges in the Bay of Bengal force an unsustainable exodus, for example. As Jerod Diamond illustrates, one collapse, say an environmental one, tends to be followed by other collapses, and the sequence can progress with a speed that always astonishes those who live to tell the tale. I believe I might most likely pass peacefully into the timeless recycling that is the biosphere in the next 20 or 30 years. On the other hand, this is a plausible vision of my demise: the awe of personified fire and ice in the Icelandic saga version of Ragnarok. As Emerson said, our ancestors beheld God and nature face-to-face; we, merely through our ancestors. I’d like to be somewhat ready for the personal introduction. My own personal passage: into peaceful sleep, a tunnel with a light and smiling ancestors, or even the Pearly Gates, who can say? Or will it be an undignified mass annihilation, whether in a “whimper” or “a bang?” If Ragnarok is my fate, then I want to try to participate in its epic dimension. Search for Paul Kingsnorth for someone trying to salvage awe and beauty from a darker vision of our ecological future. Getting toasted or devoured, sword drawn against Fafnir, the sun-swallowing wolf, seems more dignified, at least more human, than passing in my sleep among weeping loved ones, in a way… if it must be so. Given a choice of passing peacefully on the eve of destruction, or witnessing and struggling in it, I think I’d try to hang on. It is not a happy ending (is any death?) but makes a unique and fulfilling story appropriate to the circumstances, as such stories go.

Why stories? Why poetry? Perhaps all these writers are like the blind men and the elephant, each with an accurate observation but limited sense of a whole. I can’t claim to see the elephant all by myself. And others can’t see it all by themselves either. That is why we need to talk about these things.

What’s your great story? When and to whom will you tell it? Isn’t it time?

“A criticism is just a really bad way of making a request…so just make the request.”

Link to Gary Cornell’s Stemforums website

I am delighted to have another guest post by Gary Cornell. This one is a reaction to my post “Jonathan Gruber in the Hot Seat.” (Note: Gary had an excellent guest post very early on in the history of supplysideliberal.com: “Gary Cornell on Andrew Wiles.” He also had a nice guest post recently on the Mathbabe blog: “Bring Back the Slide Rule!”) Here are Gary’s thoughts about Jonathan Gruber:

After Miles posted about “L"affaire Gruber,” I emailed him about my shock that somebody who had done so much consulting for government was so lacking in “Washington smarts.” He mentioned that “economists have a tradition of frankness among themselves.” But it seems to me while this may be strongest among economists, it really is quite common for tenured academics in general. After all, as the joke goes, “tenure means never having to say you’re sorry.”

But I then went on to explaining how the National Science Foundation where I served as a rotating program director, had a very successful method of turning tenured faculty into temporary, reasonably high level government bureaucrats-who could and would get into a lot of trouble if they did or said the wrong thing! What they did was send you off to “rotator camp” for a week or so. At rotator camp you actually spent a lot of time learning how to talk - something tenured professors rarely have to worry about. For example, we were told to remember that we weren’t “giving grants” but “recommending them” or when we spoke to people we could never say we planned (as we all did) to favor young academics over senior people. (Amusingly we were told that could tell people that we would be favoring “recent Ph’D’s” over senior faculty, because saying the former made us guilty of “age discrimination” which was illegal,but the latter statement was fine!)

What I remember most vividly though, even after more than 20 years has passed, was how they ended things:

If there is only one thing you take away from these few days, let it be this: don’t do or say anything that you wouldn’t want spun by your worst enemy on the front pages of the Washington Post.

Gruber, in spite of all his governmental consulting, apparently has never learned this!

“In school, we’re taught that stories rely on ‘conflict’ and that some conflicts are internal while some are external. …Track them to their source, though, and nearly all conflicts are internal—because they all start with someone, somewhere, wanting something.”

– Scott McCloud, Making Comics: Storytelling Secrets of Comics, Manga and Graphic Novels, p. 67. My title for this quotation is Utility Function Dominance.

Philippe James recently tweeted me a link to Scott Fullwiler’s July 11, 2009 post “Why Negative Nominal Interest Rates Miss the Point.” He begins by noting

Willem Buiter, Greg Mankiw, and Scott Sumner have all recently proposed negative nominal interest rates on reserves or currency as a way to stimulate consumer spending and bank lending.

Then he mention’s Silvio Gesell’s plan, which differs from mine but also yields a negative nominal interest rate on paper currency:

The classic example of a negative nominal interest rate—long suggested by a number of economists for avoiding deflation—is a tax on currency …

Scott questions the effectiveness of this plan, saying:

Well, I don’t know about you, but my response would be pretty clear if the Fed made such an announcement: I’d stop holding currency and just use my debit card (most major purchases already aren’t done with currency, anyway). And so would most everyone else. Banks would then sell their currency back to the Fed and the Fed would pay banks reserve balances in exchange (as it usually does). I highly doubt this would lead any bank to cut its lending rates, as Mankiw thinks.

The response and result are in essence unchanged if instead you require individuals to periodically pay to have their currency “stamped” for validation (which Buiter also describes)—I would use a debit card or go to the ATM machine on the day I was going to spend.

Here Scott points to the necessity of something I emphasize every time I talk to central banks about breaking through the zero lower bound: it is important for central banks to move all four key interest rates in tandem:

If the central bank lowers just the target rate and the paper currency interest rate without lowering the interest rate on reserves, it will be just as ineffective at lowering the market interest rate as if the central bank lowers the target rate and the interest rate on reserves without lowering the paper currency interest rate. Market rates can still be pushed down if the lending rate is left higher, but a lending rate lower than the other rates would interfere with trying to push market rates up.

So pointing out that lowering one of these rates won’t do much is not an objection to negative rates. To be effective, there has to be no place to hide from the negative rates, except by either buying foreign assets (which is a capital outflow and stimulates net exports) or by actually buying something, either to invest, store, or consume. Of course the central bank should lower all the rates it controls, not just one.

In the remainder of Scott’s post, his analysis focuses on income effects. For example, even though he points out that for every saver earning less interest, there is a borrower paying less interest (and borrowers probably have higher propensities to consume than savers) he doesn’t think those offsetting effects plus the greater incentive to borrow will have much effect.

When Scott says the interest sensitivity of spending is low, that could well be true for nondurable consumption, but it is not true for durable consumption or investment. The stimulus I expect from negative interest rates is not primarily from the nondurable consumption Euler equation that is what comes to mind for many economists. It is primarily from durable consumption, investment and net exports. Indeed, even if there were no stimulus whatsoever to nondurable consumption, negative interest rates would be very powerful.

Scott also worries about the effects on bank equity of below zero interest rates. As we have all seen, there are many other mechanisms to bail out banks whose equity is too low other than keeping interest rates too high. And looking forward to the future, we should, in any case, make sure that banks go into the next recession with much, much higher levels of equity than they went into this recession. Under those circumstances, negative interest rates might make it take longer for banks to get out of their capital conservation buffer, so it would be longer before they could again pay dividends or buy back stock, but the economy would be fine. ’

Finally, in answer to Scott’s question

why not a simple payroll tax holiday, for example, as my fellow bloggers have proposed?

One answer is that negative interest rates can have a bigger effect on aggregate demand than even cutting payroll taxes all the way to zero. I should also mention that whether or not a payroll tax holiday stimulates the economy at all depends greatly on the monetary policy response. In the context of this argument it probably does have some positive effect in conjunction with the monetary policy response of staying at the zero lower bound. But away from the zero lower bound, the monetary policy response might easily cancel out the other effects of a payroll tax holiday on aggregate demand. (On this principle of short-run monetary dominance, see my column “Show Me the Money!”)

The other answer to Scott’s question is that relative to cutting interest rates to get the same effect on aggregate demand, a payroll tax holiday means higher taxes or lower spending later on–both of which are painful. Monetary stimulus is cheap, fiscal stimulus expensive. On this topic, you might like my post “Monetary vs. Fiscal Policy: Expansionary Monetary Policy Does Not Raise the Budget Deficit” has an enduring popularity. If huge amounts of government revenue fell from the sky due to, say, undersea natural gas–much more than could productively be spent on defense, scientific research and other public goods–it would be great in steady state to subsidize wages to help counteract the effect of various labor market distortions. But for most countries, that kind of government revenue doesn’t fall from the sky. It has to be raised through taxes.

“The most revolutionary ideas always sound crazy until people get used to them.”

Here is the full text of my first column on Slate, “The Paperless Economy: How Governments can and should beat Bitcoin at its own game.”

From a technical point of view, Bitcoin is far ahead of governments in its beautiful implementation of electronic money.

But Bitcoin itself is not the future of money, because it is hard to believe that governments will willingly hand over control of the world’s monetary policy to the Bitcoin algorithm. Nor should they. Keeping the value of money constant over time is difficult and requires strong, capable institutions like central banks. But looking toward the future, it is the electronic dollar (and euro and yen and pound … ) whose value should be kept constant, not yesterday’s paper currency.

Many people are attracted to the gold standard because they think of gold as maintaining its value. But like Bitcoin, the value of gold relative to the goods and services we need to buy fluctuates in the markets every day. An economic yardstick of fixed value doesn’t come that easily. It has to be engineered—and the clearest path to engineering an economic yardstick of fixed value is electronic.

The key advantage of electronic money over paper currency is this: Monetary systems based on paper currency allow for strongly positive interest rates, but not strongly negative rates; by contrast, it is easy to have interest rates on electronic money vary all the way from strongly positive to strongly negative. High interest rates make it expensive to spend now compared with waiting until later, while low interest rates encourage people to spend now. If interest rates can vary freely over a wide range, they are able to signal to households and businesses as loudly as necessary that the economy needs people to cut back on spending and save more when the economy is overheated, or cut back on saving and spend more when the economy is in a recession.

To zero in on the key problem, in our current monetary system we take for granted an interest rate of zero on paper currency. That interest rate of zero can falsely signal to households and firms that it is OK for them to hold back on spending—even at times when businesses desperately need the customers and people desperately need the jobs that extra spending would provide. Think of a one-year loan. With a positive interest rate, of, say, 2 percent, borrowers pay back their initial loan, plus 2 percent interest. With an interest rate of zero, borrowers pay back the loan with no additional costs. With a negative interest rate, of, say, minus 2 percent, borrowers pay back the loan, minus 2 percent. In effect they’re being paid for taking on a loan. Can you imagine anything that might better stimulate economic activity?

Yesterday’s paper currency is not only a barrier to speedy recovery from deep recessions—it is also a barrier to ending inflation. Many people don’t realize inflation in advanced economies such as the United States, the eurozone, and the United Kingdom is the result of conscious decisions of the Fed, the European Central Bank, and the Bank of England (with the Bank of Japan now trying to follow suit) to tolerate 2 percent inflation, in order to give monetary policy more room to maneuver. Here is the reasoning: Both households and businesses focus on interest rates in comparison with inflation when making spending decisions, so that higher inflation makes interest rates effectively lower. As economists say it, for a fixed nominal interest rate, higher inflation lowers the real interest rate. For example, if someone is paying 3 percent interest on a loan but inflation is 2 percent, then 2 percent is just making up for inflation, and only the remaining 1 percent actually gives the lender extra real value in terms of what the principal plus interest is worth.

The key takeaway message for monetary policy is that because people look at how interest rates compare with inflation, an interest rate of zero that is 2 percent below inflation is much more stimulative than an interest rate of zero when inflation is also zero. (That is why the United States got more oomph from its zero interest rates than Japan, which had an inflation rate of zero or less.)

As long as paper currency has an interest rate of zero, it is hard for other interest rates to go below zero, so the only way to get interest rates below inflation is to push inflation above zero. Take paper currency off its pedestal, and inflation is no longer necessary to provide this space for monetary policy, since interest rates can go down, instead of inflation having to go up. Then there is nothing standing in the way of ending inflation forever.

To make it possible to end recessions quickly and to end inflation forever, a government needs to take the following steps:

It has become traditional for U.S. Treasury secretaries to periodically repeat the mantra that “a strong dollar is in our nation’s interest.” I would add one word to the mantra: “A strong electronic dollar is in our nation’s interest.” A strong electronic dollar is one that works smoothly in transactions, empowers monetary policy to bring a speedy end to recessions, and keeps its value over time with no concessions to inflation.

The path to a strong electronic dollar will require bureaucratic and political fortitude. But the economic principles involved are clear. The rewards at the end of that path—the taming of the business cycle and the end of inflation—insure that some nation will blaze that trail. (My bet is on the United Kingdom.) Then the rest of the advanced nations will follow.

But make no mistake: Giving electronic money the role that undeserving paper money now holds will only tame the business cycle and end inflation. Fostering long-run economic growth, dealing with inequality, and establishing peace on a war-torn planet will remain just as challenging as they are now. But every time one set of problems is solved, it allows us to focus our attention more clearly on the remaining problems. It is time to step up to that next level.

In his radical book Fair Play (p. 16), Steven Landsburg puts forward this radical idea:

… we should care about other people’s liberty as well as our own.

In On Liberty, Chapter IV, “Of the Limits to the Authority of Society over the Individual” (paragraph 12), John Stuart Mill puts forward the same idea, and explains just how radical it is:

But the strongest of all the arguments against the interference of the public with purely personal conduct, is that when it does interfere, the odds are that it interferes wrongly, and in the wrong place. On questions of social morality, of duty to others, the opinion of the public, that is, of an overruling majority, though often wrong, is likely to be still oftener right; because on such questions they are only required to judge of their own interests; of the manner in which some mode of conduct, if allowed to be practised, would affect themselves. But the opinion of a similar majority, imposed as a law on the minority, on questions of self-regarding conduct, is quite as likely to be wrong as right; for in these cases public opinion means, at the best, some people’s opinion of what is good or bad for other people; while very often it does not even mean that; the public, with the most perfect indifference, passing over the pleasure or convenience of those whose conduct they censure, and considering only their own preference.

Part of the problem is in the limitations of the golden rule: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” That is all well and good if they have the same preferences, but not if they want something different from what you would want in the same circumstances. Until further advances in technology, we are shut out of knowing directly what the world looks like from inside someone else’s mind, and have to guess based on how we would feel. But that sometimes steers us badly off target. Giving everyone personal liberty is a safeguard against our blind meddling.

Of course, applying the golden rule at a meta-level would say “I want liberty, so I should give others liberty as well.” But there are many times when liberty is a higher law than applying the golden rule at the detailed level.

In light of the title, I should point out that, from an efficiency standpoint (without regard to politics), there may no justification for phasing in a gasoline tax increase slowly. If a national security externality were like an environmental externality, that externality should ideally be reflected in the tax rate right now. But the national security externality is actually a pecuniary externality, so it would take some nontrivial reasoning to figure out whether or not there is any justification for phasing a gasoline tax in. It is an optimal taxation problem in which money in the hands of certain parties counts negatively.

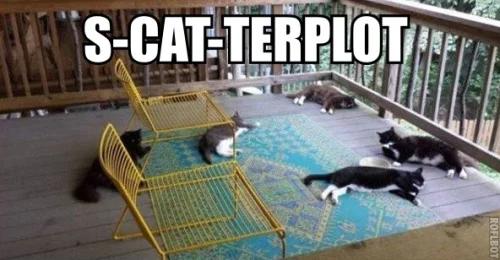

S-CAT-TERPLOT: A Comfortable Spread.

Reblogged from econlolcats. By Michael H.

As usual, econlolcats on my blog are a harbinger of good things to come. This econlolcats post heralded my Quartz column “The national security case for raising the gasoline tax right now.” (Working title: “Our Oil Weapon”).

Link to the interview on Business Insider

Here, below the line of stars, is the full text of Danny Vinik’s interview with me for Business Insider. I linked to it when it first came out on November 21, 2013, and cleared with Danny the idea that I could copy it over in full here after some time had passed, given my role in making it possible. I think Business Insider holds the copyright.

Danny Vinik and I talked for about 75 minutes. One thing I talked a lot about in the interview is that of all the possible ways to handle the demand-side problem, repealing the zero lower bound is the one that leaves us best able to subsequently pursue supply-side growth. Fiscal stimulus leaves us with an overhang of government debt that then has to be worked off by painfully higher taxes or lower spending. Going easy on banks and financial firms to prop up demand (as Larry Summers at least halfway recommends in his recent speech at the International Monetary Fund) risks another financial crisis. Higher inflation to steer away from the zero lower bound (as Paul Krugman favors) messes up the price system, misdirects both household decision-making and government policy, and makes the behavior of the economy less predictable. (On Paul Krugman, also see this column.)

Let me push a little further the case that electronic money can clear the decks on the demand side so that we can focus on the supply side with this example. Suppose you firmly believed that the demand side played no role in the real economy—that the behavior of the economy could be described well by a real business cycle model, regardless of what the Fed and other central banks do, and regardless of the zero lower bound. From that point of view, in which monetary policy only matters for inflation, electronic money would still be valuable as a way of persuading others that it was OK to have zero inflation rather than 2% inflation.

The United States has been marred in slow economic growth and a weak recovery for years now. Unemployment remains high. This is despite extraordinary efforts by the Federal Reserve to stimulate the economy. This drawn out period of low inflation and high unemployment has gotten more and more people talking about a “new normal” of mediocre growth.

Economists have been looking for ways to give central banks more power to combat recessions and prevent these long, drawn out recoveries. Larry Summers laid out this major impending economic challenge in his recent speech at the IMF. Normally, when a recession hits, central banks cut interest rates to incentivize firms to invest and to spur economic growth. But when interest rates hit zero, those banks lose one of their most important tools to combat recessions. This is called the zero lower bound.

Hitting the zero-lower bound means that interest rates cannot reach their natural equilibrium where desired investment equals desired savings. Instead, even at zero, interest rates are too high, leading to too much saving and a lack of demand. Thus we get the slow recovery.

Until recently, we hadn’t hit that bound. But since the Great Recession, we’ve been stuck up against it and the Fed has been forced to use unconventional policy tools instead. What Summers warned of is that this may become the new normal. When the next recession hits, interest rates are likely to be barely above zero. The Fed will cut them and we’ll find ourselves up against the zero lower bound yet again and face yet another slow recovery.

So what’s the answer?

University of Michigan economist Miles Kimball has developed a theoretical solution to this problem in the form of an electronic currency that would allow the Fed to bring nominal rates below zero to combat recessions. He’s been presenting his plan to different economists and central bankers around the world. Kimball has also written repeatedly about it and was recently interviewed by Wonkblog’s Dylan Matthews.

“If you have a bad recession, then firms are afraid to invest,” he told Business Insider. “You have to give people a pretty good deal to make them willing to invest and that good deal means that the borrowers actually have to be paid to tend the money for the savers.”

But paper currency makes this impossible.

“You have this tradition that as it is now is enshrined in law in various ways that the government is going to guarantee to all savers that they will get [at least] a zero interest,” Kimball said.

If the Fed lowered rates below zero in our current financial system, savers would simply withdraw their money from the bank and sit on it instead of letting it incur negative returns. The paper currency itself — because it’s something that can be physically withdrawn from the financial system — prevents rates from going negative.

This is where Kimball’s idea for an electronic currency comes in. However, unlike Bitcoin, which prides itself on its decentralization and anonymity, Kimball’s digital currency would be centralized and widely used. He would effectively set up two different types of currencies: dollars and e-dollars. Right now, your $100 bill is equal to the $100 in the bank. If you’re bank account has a 5% interest rate, you earn $5 of interest in a year and that $100 bill is still worth $100. But what would happen if that interest were -5%? Then you would lose $5 over the course of the year. Knowing this, you would rationally withdraw the $100 ahead of time and keep it out of the bank. This is where the separate currencies come in.

“You have to do something a little bit more to get the negative rate on the paper currency,” Kimball said. “You have to have the $100 bill be worth $95 a year later in order to have a -5% interest rate. The idea is to arrange things so let’s say $100 in the bank equals $100 in paper currency now, but in a year, $95 in the bank is equal to $100 in paper currency. You have an exchange rate between them.”

“After a year, I could take $95 out of the bank and get a $100 bill or if I wanted to put a $100 bill into the bank, they would credit my account with $95.”

Got that? After a year of a -5% interest rate, $100 dollars are equal to $95 e-dollars. This ensures that paper currency also faces a negative interest rate as well and eliminates the incentive for savers to hoard dollar bills if the Fed implements a negative rate. Presto! The zero lower bound is solved.

The benefits of this policy go even further though: We can say goodbye to inflation as well.

“Once you take away the zero lower bound, there isn’t a really strong reason to have 2% inflation at this point,” Kimball said. “The major central banks around the world have 2% inflation and Ben Bernanke explained very clearly why that is. It’s to steer away from the zero lower bound.”

He’s right. Back in March, Ryan Avent asked Bernanke why not have a zero percent inflation target. Bernanke answered, “[I]f you have zero inflation, you’re very close to the deflation zone and nominal interest rates will be so low that it would be very difficult to respond fully to recessions.”

But if nominal interest rates are allowed to go below zero, then the Fed has ample room to respond to recessions even if rates start out low. This is another major benefit from eliminating the zero lower bound.

What Kimball, whose blog is titled Confessions of a Supply Side Liberal, is most excited about is moving beyond the demand shortfall the economy currently faces to the supply side issues that hold back long-term growth.

“If you care at all about the future of this country, one of the things you need to realize is we need to solve the demand side so we can get back to the supply side issues that are really the tricky thing for the long run,” he said. “The way to solve the demand side issues that is the most consistent with not messing up our supply side is monetary policy and making it so we can have negative interest rates.”

At the moment, e-dollars are still only a theoretical concept, but Kimball is hopeful that they could be put into action in the near future. He believes that if a government bought in, it could be using an electronic currency in three years and reap the benefits of it soon after.

“This is going to happen some day,” he concluded. “Let me tell you why. There are a lot of countries in the world and some country is going to do this and it’s going to be a whole lot easier for other countries to do it once some country has stepped out.”

“Why, indeed, do we have public schools at all? There are advantages to having an educated public, and there are at least arguments to the effect that the private sector will undersupply education. But that’s an argument for government subsidies or vouchers; it’s not an argument for the government to actually run the schools. The reason the government wants to run schools is so that it can control what is taught. I hope that makes people uncomfortable.”

– Steven E. Landsburg, Fair Play, p. 31

New Orleans’ Recovery School District is doing a lot of things right.

I want to hear what everyone really thinks. So I hate it when people get punished for being frank about their views. Jonathan Gruber is in that situation now. If you haven’t seen it, it is well worth the 55 seconds to watch this video of Jonathan’s comments. Then to see an example of the trouble this has brought him, take a look at what Peggy Noonan wrote in her November 21, 2014 opinion piece in the Wall Street Journal (to jump over the paywall, google the title “The Nihilist in the White House”):

ObamaCare … has been done in now by the mindless, highhanded bragging of a technocrat who helped build it, and who amused himself the past few years explaining that the law’s passage was secured only by lies, and the lies were effective because the American people are stupid. Jonah Goldberg of National Review had a great point the other day: They build a thing so impenetrable, so deliberately impossible for any normal person to understand, and then they denigrate them behind their backs for not understanding.

One is most likely to be punished for being frank about one’s views if (a) one has not been frank about them all along and (b) if one’s views–or attitudes communicated along with those views–have unappealing aspects to them. So, with due allowance for the constraints one is under, one should (a) seek to be as frank as possible early on and (b) strive for views and attitudes that are as enlightened as possible to begin with.

The other lesson from Jonathan Gruber’s experience is that, more and more, one must be ready for everything one says to be totally public. For that, I think it is good preparation to have had a blog at some point during one’s career (ideally starting early enough that any mistakes or infelicities can be put down to the inexperience of youth), since blogging seriously involves saying many, many things, all of which are intended to be fully public.

Note: On the subject of telling the truth, you might be interested in these two posts: