Corbett Schmitz: Should Social Security Switch to a Defined Contribution Plan?

This is a guest post by my “Monetary and Financial Theory” student Corbett Schmitz. Corbett’s answer is “Yes.” Corbett argues his case well.

One issue Corbett does not address is the effect of a shift to a defined contribution plan on the amount of redistribution in social security. There, it is important to recognize that social security has much less redistribution in it than most people assume. Except at the very bottom, what redistribution seems to be there in the size of the benefit check is offset to a surprisingly large percentage by the fact that richer people tend to live longer, and therefore tend to draw on Social Security for a longer time.

Just recently, I had the opportunity to have dinner with my dad. Given our mutual interests, our conversation naturally drifted towards finance. My dad playfully joked how excited he is to start receiving pension checks in just a few years. Even though these checks will be small, I responded jealously; when I start working this fall, there will be no pension program waiting.

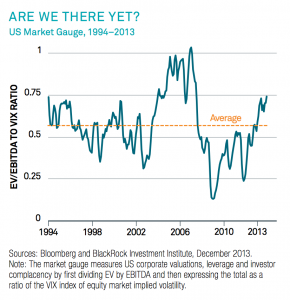

This shift away from pension programs is not unique to my father and me. Over the last 40 years, many employers have switched away from pension retirement plans (more generally called defined benefit (DB) plans), for defined contribution (DC) plans (like 401K’s). Under DB plans, employers pay a predetermined amount of cash to former employees after those employees reach retirement age. Under DC plans, employers set aside a certain amount of money each year to assist employees in developing a retirement savings account. As the graph below shows, the shift away from DB plans to DC plans has been staggering. Since 1979, for employees lucky enough to have corporate-sponsored retirement plans, enrollment in DB plans has dropped 57% while enrollment in DC plans has grown 55%.

This transition to DC plans is largely due to an increase in life expectancy rendering DB plans unsustainable (ie: as people live longer they collect benefits longer, increasing the onus placed on firms and requiring progressively more cash to fund DB plans). This year, the Society of Actuaries released new life expectancies for the first time since 2000. In the last 14 years, men’s life expectancy has grown from 82.6 years to 86.6 and women’s has grown from 85.2 years to 88.8. Driven by increases in technology and better health care, this upward trend is only expected to increase. Prior to this revision of life expectancy, outstanding private sector liabilities related to DB plans hovered around $2 trillion. After this revision, these liabilities are expected to grow at least another 7%, bringing outstanding liabilities to $2.14 trillion, which represents over 13% of US GDP!

As anyone familiar with a balance sheet knows, liabilities must be paid, and doing so is no easy task. Considering that life expectancy is expected to grow further, it’s not surprising that firms are switching to DC plans from DB, as doing so helps reduce total liabilities. Specifically, the switch to DC from DB helps reduce liabilities by shifting investment risk away from firms and to retirees. Under a DB plan, firms are responsible for paying a set amount of retirement income in the future. To generate this future outflow, firms invest cash now, hoping it will grow enough to fund the promised pension payments. Unfortunately, very few firms invest enough to meet the entire defined benefit payment, as most firms assume unrealistically high returns when making investments. Doing so causes many firms to drastically underfund their DB plans, generating enormous liabilities (with potentially crippling consequences) in the process. In contrast, a DC plan is much more sustainable because it does not promise any future cash payments, and therefore does not create any liabilities. Rather, a DC plan only requires firms to presently invest cash on behalf of its employees, with the future retiree bearing the investment risk.

Does this mean that the switch from DB to DC is a bad thing for retirees? After research, I believe it’s a wash. That said, I did find some strong evidence suggesting that, under the right circumstances, DC plans can offer higher returns than DB. A study by Dartmouth College found that the typical DC 401K-retirement plan, “provides an expected annuitized retirement income that is higher across nearly every point in the probability distribution than the typical defined benefit plan.”

If you check my sources, however, you’ll see that this study was performed before the Great Recession, when the market collapse took a huge toll on many nest eggs. But even with such a dramatic downturn, DB and DC plans still perform similarly; over the last ten years, DB benefits have only outperformed DC plans by 0.86%. Furthermore, most of this underperformance is due to a failure of individuals to make maximum contributions to their plan.

Based on this data, I should be indifferent between DB and DC plans because I know my retirement income will be similar under both optionsHowever, I am largely in favor of DC plans because they eliminate the liabilities associated with DB payments. So how is this conclusion relevant to social security? Personally, I believe a gradual shift from government-sponsored DB payments (ie: social security payments) to government-mandated DC contributions could help solve social security’s sustainability issue.

According to the Heritage Foundation, the expected insolvency date of social security is approaching faster and faster; in the last five years, this date has declined 8 years and is currently set at 2033. However, given current conditions, the Heritage Foundation predicts that insolvency could come as early as 2024 (when originally started, social security was designed to remain solvent until 2058). Given that social security represents 22% of the US federal budget, insolvency is no trivial issue, and reform is needed sooner rather than later.

I propose that this reform should include a switch from a DB plan to a DC plan. While social security payments should remain intact for current and soon-to-be beneficiaries, I believe that social security tax should gradually be replaced with a social security “withholding.” For example, if social security tax is currently 10% of income, I propose it should be reduced to 5% of income in, let’s say, ten years. In those ten years, the social security withholding should grow to 5% of income. Eventually, social security tax should fall to 0% of income and be replaced entirely by the withholding (Personally, because I think savings is so important, I think that this withholding should ultimately represent a higher percentage of income than social security tax ever has or will).

Like a 401K contribution, I propose that this withholding should be invested, tax-free, in a retirement account on an individual basis. Essentially, this withholding is equivalent to automatic-enrollment in a government-mandated 401K plan. As individuals continue to work, instead of paying taxes to fund social security, they will pay withholdings to help fund their own retirement.

With respect to investment decisions, the government should have a default option requiring individuals to purchase relatively safe, well-diversified indexes (like a global fund). If individuals would like, they should be allowed to invest up to half of their withholdings on indexes of their choice (I limit investment to indexes because, as Malkiel makes obvious in A Random Walk Down Wall Street, indexes are the safest way to make money. On average, even professional money mangers cannot outperform indexes that track the aggregate market). Once individuals reach retirement age (ie: the age they would have qualified for social security) they can begin making withdrawals from this retirement account.

My proposed plan has some similarities to George W. Bush’s proposal of private savings accounts in early 2000. Under the most successful of Bush’s privatization proposals, taxpayers could divert 4% of taxable wages or a maximum of $1000 from FICA payments to fund personally managed retirement accounts. These contributions would not replace, but rather would offset, social security’s existing DB payments. Workers would then have the option to invest their private accounts in 5 different funds.

The key difference between my proposal and Bush’s proposal is the long-term implications for social security. Bush’s proposal aimed to prolong, not eliminate, the insolvency date of social security by offsetting social security’s DB payments with some DC payments. In contrast, my plan proposes a gradual but complete transition of social security from a DB plan to a DC plan, thereby rendering insolvency irrelevant.

While my plan is not perfect, I believe it effectively addresses the sustainability of social security by gradually eliminating government-paid DB benefits. Furthermore, it forces individuals to save for retirement by replacing a significant portion of their taxable income with government-mandated savings. I believe this system, by eliminating the liabilities related to DB retirement plans, is much more sustainable than social security, and it has the double-benefit of encouraging savings and investment literacy. As always, I welcome any and all suggestions as we collectively try to address the issue of social security sustainability.

Update by Miles: I had a Twitter exchange with Andrew Burton about financing the transition, where I was thinking of the capital budgeting principles you can see in “Capital Budgeting, the Powerpoint File.” In addition, Gary Burtless gives some great comments on the Facebook version of this post.

Gary Burtless: First off, I think Mr. Schmitz is wrong about this: “This transition to DC plans is largely due to an increase in life expectancy rendering DB plans unsustainable.” The shift was due instead to (#1) ERISA’s requirement that employers fund their DB plans and pay for insurance in the event the employer entered bankruptcy with an underfunded plan; and (#2) Employers’ recognition of the risks they were taking on by guaranteeing future annuities with risky assets (60% equities). The rise in longevity has been underway for 100 years, and there have been no surprises since the early 1980s, when the phase-out of DB plans got underway.

Second, I think Mr. Schmitz is probably wrong about the potential welfare gain from converting Social Security from a DB to a DC plan. Rising longevity is essentially irrelevant in thinking about this question. I suspect the great majority of working citizens prefer DB to DC pensions, because they believe their retirement incomes will be more predictable (and they like that predictability). While individual employers, including private, municipal, and county government employers, cannot guarantee future DB pensions, the U.S. government can (at least up to a limit) given its ability to tax residents, few of whom are likely to move out of the country to avoid this tax. In other words, whereas it may be hard for the overwhelming majority of individual employers to guarantee future DB pensions without backing that guarantee with very, very safe (and low return) assets, it is easier and more credible for our national government to do the same thing. In light of the fact that workers seem to prefer DB over DC-style pensions, why shouldn’t rational citizens support national provision of such pensions? I think polling evidence supports the idea that U.S. citizens strongly favor continuation of Social Security as it currently exists, that is, as a DB plan, even if they have to pay higher payroll taxes to maintain the system. My guess is that converting the system to a DC plan, and reducing the assurance of a (semi-) guaranteed flow of future benefits, would reduce rather than increase worker and citizen welfare.

My answer there is this: “The government definitely has a comparative advantage in providing annuities, but it could do so in a market way.” What I have in mind is that on its liability side, in addition to Treasury Bill’s, the US Sovereign Wealth Fund I advocate should provide a variety of different kinds of annuities at prices that give the taxpayers implicitly providing those annuities a fair shake. See

- Why the US Needs Its Own Sovereign Wealth Fund

- How to Stabilize the Financial System and Make Money for US Taxpayers

- How a US Sovereign Wealth Fund Can Alleviate a Scarcity of Safe Assets

- Libertarianism, a US Sovereign Wealth Fund, and I

- Miles’s First TV Interview: A US Sovereign Wealth Fund

- Roger Farmer and Miles Kimball on the Value of Sovereign Wealth Funds for Economic Stabilization