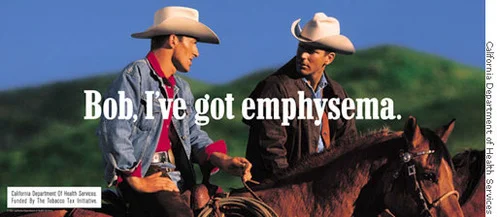

An alternative is to try to highlight the alternative, desired behavior.

5. Practical Value: News you can use.

This dimension is fairly straightforward. But Jonah gives this interesting example of a video about how to shuck corn for corn on the cob that went viral in an older demographic where not many things go viral. He also points to the impulse to share information of presumed practical value as part of the reason it is so hard to eradicate the scientifically discredited idea that vaccines cause autism.

6. Stories: Information travels under the guise of idle chatter.

Here, Jonah uses the example of the Trojan horse, which works well on many levels: the horse brought Greek warriors into Troy, and the story of the Trojan horse brings the idea “never trust your enemies, even if they seem friendly” deep into the soul. He points out just how much information is carried along by good stories.

But Jonah cautions that to make a story valuable, what you are trying to promote has to be integral to the story. Crashing the Olympics and doing a belly flop makes a good story, but the advertising on the break-in diver’s outfit was not central to the story and was soon forgotten. By contrast, for Panda brand Cheese, the Panda backing up the threat “Never say no to Panda” is a memorable part of the stories of Panda mayhem in the cheese commercials, and Dove products at least have an integral supporting role to play in Dove’s memorable Evolution commercial illustrating the extent to which much makeup and photoshopping are behind salient images of beauty in our environment.

Applied Memetics for the Economics Blogger

Here are a few thought about how to use Jonah’s insights in trying to make a mark in the blogosphere and tweetosphere.

1. Social Currency

Inner Remarkability: I find the effort to encapsulate the inner remarkability of each post or idea in a tweet an interesting intellectual challenge. One good way to practice this is a tip I learned from Bonnie Kavoussi: try to find the most interesting quotation from someone else’s post and put that quotation in your tweet. That will win you friends from the authors of the posts, earn you more Twitter followers (remember that the author of the post will have a strong urge to retweet if you are advertising herhis post well), and hone your skills for when you want to advertise your own posts on Twitter.

Leverage Game Mechanics: In the blogosphere and on Twitter, we are associating with peers. Much of what they want is similar to what w want–to be noticed, to get our points across, to get new ideas. So helping them to win their game is basically a matter of being a good friend or colleague. For example, championing people’s best work and being generous in giving credit will win points.

Make People Feel Like Insiders: When writing for on online magazine (Quartz in my case), it feels I need to write as if the readers are reading me for the first time. By contrast, a blog is tailor-made to make readers feel like insiders. So it is valuable to have an independent blog alongside any writing I do for an online magazine.

2. Triggers

A common piece of advice to young tenure-track assistant professors is to do enough of one thing to become known for that thing. This is consistent with Jonah’s advice about triggers. Having people think of you every time a particular topic comes up is a good way to make sure people think of you. That doesn’t mean you need to be a Johnny-one-note, but it does mean the danger of being seen as a Johnny-one-note is overrated. Remember that readers can easily get variety by diversifying their reading between you and other bloggers. So they will be fine even if your blog specializes to one particular niche, or a small set of niches.

On Twitter, one way to associate yourself with a particular trigger is to use a hashtag. In addition to the hashtag #ImmigrationTweetDay that Adam Ozimek, Noah Smith and I created for Immigration Tweet Day, I have made frequent use of the hashtag #emoney, and I created the hashtag #nakedausterity.

3. Emotion

Economists often want to come across as cool and rational. But many of the most successful bloggers have quite a bit of emotion in their posts and tweets. I think Noah Smith’s blog Noahpinion is a good example of this. Noahpinion delivers humor, indignation, awe, and even the sense of anxiety that comes from watching him attack and wondering how the object of his attack will respond.

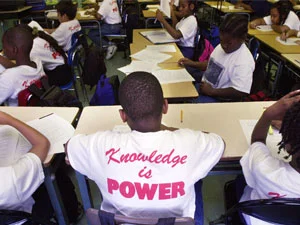

One simple aid to getting an emotional kick that both Noah and I use is to put illustrations at the top of most of our blog posts. I think more blogs would benefit from putting well-chosen illustrations at the top of posts.

4. Public

The secret to making a blog more public is simple: Twitter. Everything on Twitter is public, and every interaction with someone who has followers you don’t is a chance for someone new to realize you exist. Of course, you need to be saying something that will make people want to follow you once they notice that you exist.

Facebook helps too. I post links to my blog posts on my Facebook wall and have friended many economists.

Finally, the dueling blog posts in an online debate tend to attract attention.

5. Practical Value

In “Top 25 All-Time Posts and All 22 Quartz Columns in Order of Popularity, as of May 5, 2013,” I point out the two posts that are slowly and steadily gaining on posts that were faster out of the block:

I think the reason is practical value. Economists love to understand the economy, but they also have to teach school. They are glad for help and advice for that task.

6. Stories

Let me make the following argument:

- a large portion of our brains is devoted to trying to understand the people in our social network;

- so the author of a blog is much more memorable than a blog, and

- a memorable story about a blog is almost always coded in people’s brains as a memorable story about the author of the blog.

Thus, to make a good story for your blog, it is important to “let people in.” That is, it pays off to let people get to know you. The challenge is then to let people get to know you without making them think you are so “full of yourself” that they flee in disgust. Economists as a rule have a surprisingly high tolerance for arrogance in others. But if you want non-economists to stick with you, you might want to inject some notes of humility into what you write.

One simple way to let people get to know you without seeming arrogant is to highlight a range of other people you think highly of. The set of people you think highly of is very revealing of who you are. (Of course, the set of people you criticize and attack is also very revealing of who you are, but not in the same way.)

Summary

Jonah Berger’s book Contagious is one of the few books in my life where I got to the end and then immediately and eagerly went back to the beginning to read it all over again for the second time. (I can’t remember another one.) Of course, it is a relatively short book. But still, it took a combination of great stories, interesting research results, and practical value for me as a blogger to motivate me to read it twice in quick succession. I recommend it. And I would be interested in your thoughts about how to get a better chance of having blog posts and tweets go viral.

Further Reading

Jonah recommends two other books that with insights into what makes an idea successful:

- Malcolm Gladwell’s The Tipping Point: is a fantastic read. But while it is filled with entertaining stories, the science has come a long way since it was released over a decade ago.”