The Politics of Electronic Money: Take 2 →

By the way, here is a link to my previous storify post “The Politics of Electronic Money: Take 1.”

A Partisan Nonpartisan Blog: Cutting Through Confusion Since 2012

By the way, here is a link to my previous storify post “The Politics of Electronic Money: Take 1.”

In my introductory macroeconomics class, I recommend that my students read Daniel Coyle’s book The Talent Code: Greatness Isn’t Born. It’s Grown. Here’s How.(Daniel Coyle also has a website called “The Talent Code”)There are two key messages of that book, important both for gaining skill in economics and for thinking about the economics of education and economic growth:

Talent is Overrated. Geoff Colvin’s book Talent is Overrated has the same two messages. Shane Parrish, in his Farnam Street blog post “What is Delieberate Practice?” ably pulls from Talent is Overrated a description of deliberate practice.

Shane begins with these two quotations from Talent is Overrated indicating the difference between deliberate practice and what most people think of when they think of practice:

Shane clarifies:

Most of what we consider practice is really just playing around — we’re in our comfort zone.

When you venture off to the golf range to hit a bucket of balls what you’re really doing is having fun. You’re not getting better. Understanding the difference between fun and deliberate practice unlocks the key to improving performance.

Shane then structures the rest of his post by this that Geoff Colvin says of deliberate practice:

1. Deliberate practice is designed to improve performance. Teachers can help in that design. As Geoff Colvin writes:

Shane comments:

Teachers, or coaches, see what you miss and make you aware of where you’re falling short.

With or without a teacher, great performers deconstruct elements of what they do into chunks they can practice. They get better at that aspect and move on to the next.

Noel Tichy, professor at the University of Michigan business school and the former chief of General Electric’s famous management development center at Crotonville, puts the concept of practice into three zones: the comfort zone, the learning zone, and the panic zone.

Most of the time we’re practicing we’re really doing activities in our comfort zone. This doesn’t help us improve because we can already do these activities easily. On the other hand, operating in the panic zone leaves us paralyzed as the activities are too difficult and we don’t know where to start. The only way to make progress is to operate in the learning zone, which are those activities that are just out of reach.

2. Deliberate practice can be repeated a lot, with appropriate feedback.

Shane gives these two quotations from Talent is Overrated:

Shane points out that if results must be subjectively interpreted, it is valuable not to have to rely entirely on one’s own opinion to judge the results. A coach can provide such a second opinion. But sometimes all it takes is a friend with good judgment.

3. Deliberate practice is highly demanding mentally and isn’t much fun.

Shane writes

Doing things we know how to do is fun and does not require a lot of effort. Deliberate practice, however, is not fun. Breaking down a task you wish to master into its constituent parts and then working on those areas systematically requires a lot of effort.

Indeed, Geoff Colvin claims that it is hard to do deliberate practice for more than four or five hours a day, or for more than ninety minutes at a stretch.

Deliberate practice can also be embarrassing. Shane quotes from Susan Cain’s book, Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking this claim:

Presumably, a tutorial by a good coach is even better than doing deliberate practice alone. But some people do manage deliberate practice alone. A wonderful example is Ben Franklin.

A detailed example of deliberate practice: Ben Franklin. I remember vividly from my own reading of Talent is Overrated this passage Shane quotes about Ben’s program for improving his writing:

Other Readings. Shane recommends this New Yorker article by Dr. Atul Gawande.Many others have written online about deliberate practice, as googling the words “deliberate practice” indicates. One I stumbled across in my googling was Justin Musk’s excellent post “the secret to becoming a successful published writer: putting the deliberate in deliberate practice.”

A Plea: I would love to see more in the economics blogosphere about what deliberate practice looks like for gaining skill in economics.

Some amazing futuristic architecture I didn’t know existed.

Reblogged from thekhooll.

Here is the full text of my 25th Quartz column, that I coauthored with Yichuan Wang, “Autopsy: Economists looked even closer at Reinhart and Rogoff’s data–and the results might surprise you.” It is now brought home to supplysideliberal.com (and soon to Yichuan’s Synthenomics). It was first published on May 14, 2013. Links to all my other columns can be found here.

If you want to mirror the content of this post on another site, that is possible for a limited time if you read the legal notice at this link and include both a link to the original Quartz column and the following copyright notice:

© June 12, 2013: Miles Kimball and Yichuan Wang, as first published on Quartz. Used by permission according to a temporary nonexclusive license expiring June 30, 2014. All rights reserved.

(Yichuan has agreed to extend permission on the same terms that I do.)

In order to predict the future, the ancient Romans would often sacrifice an animal, open up its guts and look closely at its entrails. Since the discovery of an Excel spreadsheet error in Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff’s analysis of debt and growth by University of Massachusetts at Amherst graduate student Thomas Herndon and his professors Michael Ash and Robert Pollin, many economists have taken a cue from the Romans with the Reinhart and Rogoff data to see if there is any hint of an effect of high levels of national debt on economic growth. The two of us gave our first take in analyzing the Reinhart and Rogoff data in our May 29, 2013 column. We wrote that “…we could not find even a shred of evidence in the Reinhart and Rogoff data for a negative effect of government debt on growth.”

Our further analysis since then (here, and here), and University of Massachusetts at Amherst Professor Arindrajit Dube’s analysis since then and full release of his previous work (here, here, and here) in response to our column have only confirmed that view. (Links to other reactions to our earlier column can be found here.) Indeed, although we have found no shred of evidence for a negative effect of government debt on growth in the Reinhart and Rogoff data, the two of us have found at least a mirage of a positive effect of debt on growth, as shown in the graph above.

The point of the graph at the top is to find out if the ratio of debt has any relationship to GDP growth, after isolating the part of GDP growth that can’t be predicted by past GDP growth alone. Let us give two examples of why it might be important to adjust for past growth rates when looking at the effect of debt on growth. First, if a country is run badly in other ways, is likely to grow slowly whatever its level of debt. In order to see if debt makes things worse, it is crucial to adjust for the fact that it was growing slowly to begin with. Second, if a country is run well, it is likely to grow fast while it is in the “catch-up” phase of copying proven techniques from other countries. Then as it gets closer to the technological frontier, its growth will naturally slow down. If getting richer in this way also tends to lead through typical political dynamics to a larger welfare state with higher levels of debt, one would see high levels of debt during that later mature phase of slower growth. This is not debt causing slow growth, but economic development having two separate effects: the slowdown in growth as a country nears the technological frontier, and the development of a welfare state. Adjusting for past growth helps us adjust for how far along a country is in its growth trajectory.

In the graph, if “GDP Growth Relative to Par” is positive, it means GDP growth is higher in the next 10 years than would be predicted by past GDP growth alone. If “GDP Growth Relative to Par” is negative, it means GDP growth is lower in the next 10 years than would be predicted by past GDP growth. (Here, in accounting for the effect of past GDP growth, we use data on the most recent five past years individually, and the average growth rate over the period from 10 years in the past to five years in the past.) The thick red line shows that, overall, high debt is associated with GDP growth just a little higher than what one would guess from looking at the past record of GDP growth alone. The thick blue curve gives more detail by showing in a flexible way what levels of debt are associated with above par growth and what levels of debt are associated with below par growth. We generated it with standard scatterplot smoothing techniques. The thick blue curve shows that, in particular, GDP growth seems surprisingly high in the range from debt about 60% of GDP to debt about 120% of GDP. Higher and lower debt levels are associated with future growth that is somewhat lower than would be predicted by looking at past growth alone. Interestingly, debt at 90% of GDP, instead of being a cliff beyond which the growth performance looks much worse, looks like the top of a gently rounded hill. If one took the tiny bit of evidence here much, much more seriously than we do, it would suggest that debt below 90% of GDP is just as bad as debt above 90% of GDP, but that neither is very bad.

Where does the evidence of above par growth in the range from 60% to 120% of GDP come from? Part of the answer is Ireland. In particular, all but one of the cases when GDP growth was more than 2.5% per year above what would be expected from looking at past growth occurred in a 10-year period after Ireland had a debt to GDP ratio in the range from 60% to 120% of GDP. It is well-known that Ireland has recently gotten into trouble because of its debt, but what does the overall picture of its growth performance over the last few decades look like? Here is a graph of Ireland’s per capita GDP from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis data base:

The consequences of debt have reversed some of Ireland’s previous growth, but it is still a growth success story, despite the high levels of debt it had in the 1980s and ’90s.

In addition to Ireland, a bit of the evidence for good growth performance following high levels of debt comes from Greece. As the graph below shows, Greece has had more impressive growth in the last two decades than many people realize, despite the hit it has taken recently because of its debt troubles.

We did a simple exercise to see if the bump up in the thick blue curve in the graph at the top is entirely due to Ireland’s and Greece’s growth that has been reversed recently because of their debt troubles. To be sure that the bad consequences of Ireland’s and Greece’s debt for GDP in the last few years were accounted for when looking at the effect of debt on growth, we pretended that the recent declines in GDP had been spread out as a drag on growth over the period from 1990 to 2007 instead of happening in the last few years. Then we redid our analysis. Making this adjustment to the growth data is a simple, if ad hoc, way of trying to make sure that the consequences of Irish and Greek debt are not missed by the analysis.

Imagining slower growth earlier on to account for Ireland’s and Greece’s recent GDP declines makes the performance of Ireland and Greece in that period from 1990 to 2007 look less stellar. The key effect is on the thick blue curve estimating the effect of debt on growth. Looking closely at the graph below after adjusting Ireland’s and Greece’s growth rates, you can see that the bump up in the thick blue curve in the range where debt is between 60% and 120% of GDP has been cut down to size, but it is still there. So the bump cannot be attributed entirely to Ireland and Greece “stealing growth from the future” with their high levels of debt.

We want to stress that there is no real justification for making the adjustment for Ireland and Greece that we made except as a way of showing that the argument that Ireland and Greece had high growth in the 1990s and early 2000s, but now have had to pay the piper is not enough to turn the story about the effects of debt on growth around.

There are three broader points to make from this discussion of Ireland and Greece.

Understanding all of this matters because, as Mark Gongloff of Huffington Postwrites:

Reinhart and Rogoff’s 2010 paper, “Growth in a Time of Debt,” … has been used to justify austerity programs around the world. In that paper, and in many other papers, op-ed pieces and congressional testimony over the years, Reinhart and Rogoff have warned that high debt slows down growth, making it a huge problem to be dealt with immediately. The human costs of this error have been enormous.

Even though there are many effective ways to stimulate economies without adding much to their national debt, the primary remedies for sluggish economies that are actually on the table politically are those that do increase national debt, so it matters whether people think debt is damning or think debt is just debt. It is painful enough that debt has to be paid back (with some combination of interest and principal), and high levels of debt may help cause debt crises like those we have seen for Ireland and Greece. But the bottom line from our examination of the entrails is that the omens and portents in the Reinhart and Rogoff data do not back up the argument that debt has a negative effect on economic growth.

‘The Descent of the Modernists’, cartoon by E. J. Pace, first published in Seven Questions in Dispute by William Jennings Bryan (1924). (cmnotes gives some nice autobiographical details.)

The 1924 cartoon above is reblogged from isomorphismes. By this standard I am a descended Modernist.

What I find intriguing about the cartoon is the contrast between how each of these beliefs sounded to me when I believed in Mormonism and how they sound to me now. Here is where I stand today on the issues highlighted in the cartoon:

Now behold, a marvelous work is about to come forth among the children of men [and women]. Therefore, O ye that embark in the service of God, see that ye serve [God] with all your heart, might, mind and strength, that ye may stand blameless before God at the last day. (D&C 4:1,2)

Working for the greatest of all things that can come true with all our heart, might, mind and strength is a worthy calling for Modernists. Our responsibility is great. It is only by our diligent efforts that the world can be saved in our day, and that humankind and its descendants can move further down the path toward bring God fully into being in a day yet to come.

Here is a link to the HuffPost Live segment “Basic Economics are Killing America.” I appeared in the segment along with Mark Gongloff, Umair Haque, Andrea Castillo and the host, Mike Sacks. I thought we had a great discussion.

I was pleased to have Umair strongly agree with me in urging that all journalists and economic policymakers who deal with economics read Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig’s book

as a way to get past the confusion created by bank lobbyists.

Paul Romer is one of the economists I respect most. I wrote about Paul Romer in my post “Paul Romer on Charter Cities,” and I have given the link to his Wikipedia bio under his photo above. I am one of several people who encouraged him to start blogging, arguing that blogging is the way to reach young economists, who are a force to be reckoned with for the world’s future. Paul can be found on Twitter here.

Soon after I published my first column on electronic money, How Subordinating Paper Money to Electronic Money Can End Recessions and End Inflation, I received an invitation to a meeting put together by Paul’s Urbanization Project on the cashless society. Here is Paul’s account of that meeting, which first appeared here on Paul’s Urbanization Project blog. Thanks to Paul for his permission to reprint that account here, as a guest post.

In November of 2012, the Urbanization Project hosted a workshop on “The Cashless Society” that focused both on the implications of cashlessness for monetary policy and crime and on related developments in biometric technologies, with particular emphasis on the status of India’s UID project. This post provides a summary of the general consensus that emerged from these discussions.

Experience has show that any discussion about changes in payment systems will activate strong passions about the balance between tyranny and independence, particularly in the United States. Rational discourse about payment systems will be hindered by these passions and by the technical difficulty of monetary theory.

Creating a strong but accountable state is, of course, the essence of good governance. We need states that are strong enough to enforce laws, which are required to achieve efficient outcomes. We must also be sure that the individuals who are part of the state must themselves follow the law. Moreover, in holding the people who administer the state accountable, we must guard against a political process that creates an opening for powerful private actors to use the state for narrow private purposes, e.g. when incumbents prevent entry by new competitors.

These perennial concerns are closely related to questions about how best to protect privacy and individual freedom and to prevent firms from using strategies that use obscurity and complexity to undermine the power of competition. Given how powerful private actors have become in the online world, it is unclear whether the greater risk now springs from a state that is too strong to be held accountable or too weak to maintain the essentials necessary for consumers to benefit from safety and competitive markets.

It is unclear whether the type of privacy that an anonymous payment system based on hand-to-hand payments of currency is in fact an effective mechanism for holding a government accountable. Maintaining a payments system based on fiat currency seems, on its face, to be an implausible way to hold a state that stops obeying the law in check — the monetary authority could simply use inflation to destroy this payments system.

Based on extensive experience in India and in smaller experiments in other developing countries, there are feasible, low cost biometric identification systems that could support electronic payment systems, systems that could replace the use of hand-to-hand currency. In many developing countries, where it is the weakness of the state that poses more of a threat to daily life, these systems may be welcomed as more effective mechanisms for citizens to get benefits from the market system and from the state.

Within any jurisdiction, a prohibition on the use of paper currency could displace certain types of criminal activity, e.g. money laundering that brings cash from drug gangs into the banking system. It could raise the cost and/or reduce the incidence of some local criminal activities, but only if some substitute form of payment did not develop that provides an equal level of anonymity. Hand-to-hand exchange of a commodity like gold is one possibility. Electronic systems like bitcoin, coupled with pervasive internet connected mobile devices, might be another. But all such systems leave extensive electronic records of transactions, so they might expose criminal enterprises to more risk of detection and prosecution than systems based on hand-to-hand currency.

Prohibiting the possession of currency would remove the “zero nominal bound” as a constraint on countercyclical monetary policy. Nevertheless, one surprising conclusion from the discussion was that this should not be counted as an advantage of a prohibition on the possession of currency. One of the participants in the conference, Miles Kimball, pointed out that monetary authorities already have feasible mechanisms that they could use to avoid this constraint even when hand-to-hand currency continues to circulate. In the US, we have already adopted one of the key required measures: non-zero interest payments on banks’ reserves at the Fed, at a rate that can be set by the monetary authority.

This rate could easily be set to a negative value. The next step under the Kimball proposal is to establish an exchange rate between currency and the reserves held at the Fed and to identify bank reserves as the unit of account. This exchange rate could deviate from 1 unit of reserves per unit of currency. If, for example, one dollar of paper currency purchased only 0.98 dollars in reserves, someone who makes a purchase with paper currency could face a 2% surcharge. (Many travelers who purchase foreign exchange overseas have already encountered a value for a paper bill that is slightly less than a claim on a bank in the form of a travelers check.) In practice, it is likely that many merchants would not impose this charge on small purchases. It would matter only for organizations like banks that make big exchanges of reserves for currency and vice versa. In effect, this would amount to having the monetary authority issue two types of currency and manage the exchange rate between them.

Under the Kimball proposal, central banks would probably have enough room to stimulate the economy if this exchange rate deviated from strict 1 to 1 equality only temporarily and only by a relatively small amount. For example, by letting the value of currency fall relative to reserves by a few percent per year for a year or so while nominal interest rates are negative, then recovering back to par soon thereafter.

The other possibility that emerged from the discussion was that a central bank that wanted to “tax” the use of currency without prohibiting it outright could let the value of the paper currency depreciate forever relative to reserves, e.g. by 10% per year. When the exchange rate between currency and reserves was large enough, merchants would presumably charge more for payment in paper currency, just as merchants near the US-Canada border charged more for payment in Canadian dollars than for payment in US dollars when the exchange rate between the two types of dollars fell to 0.8 Canadian dollars per US dollar.

The surprising conclusion was that by managing the exchange rate between currency and bank reserves, the central bank could remove the zero lower bound and could tax the use of currency, which would tax criminal enterprises that rely on currency. So a full prohibition on the use of currency could be viewed as a limiting version of less extreme policies that tax currency by letting its value depreciate relative to bank reserves. Because prices and inflation would be denominated in units of bank reserves, this type of policy can tax currency without causing inflation and without inducing any of the distortions associated with inflation.

In fact, as Kimball has noted, this policy is the only policy that has been proposed that has any credible claim to offering a monetary environment with zero inflation.*

* Note added 6-13: Conventional monetary policy can of course yield zero inflation (or negative inflation for that matter, as we had during the Great Depression.) Policies that do this without solving the problem of the zero nominal bound will not be credible in the sense that they will eventually be abandoned once people have experience with the high cost that comes from giving up the ability to implement a counter-cyclical monetary policy.

TAGS: Biometric Identification, Cashless Society, Crime, Governance, Monetary Policy, Technologies

Here is my own account of that meeting, taken from the current draft of my paper “Breaking Through the Zero Lower Bound" (download):

At a small working group of NYU’s Urbanization Project including Paul Romer, Miles Kimball and others that met on November 30, 2012, two variants of the crawling peg were discussed. The one above in which, assuming positive steady-state real rates, there is an eventual return to par between electronic money and paper money in normal times, and another variant for use in environments that have large underground economies that are difficult to tax. In such an environment, paper currency–which is advantageous for participants in the underground economy—would continually depreciate at a rate meant to generate substantial revenue but stop short of leading those in the underground economy to primarily use a foreign currency or some type of commodity money instead of the depreciating domestic paper currency. (There might be border controls on the importation of foreign paper currency, without any restrictions on well-documented electronic accounts in foreign money.) Since there is widespread use of domestic paper currencies even in countries with substantial inflation, it should be possible to generate quite a bit of seignorage revenue. The interesting thing about this kind of seignorage revenue is that it is at least theoretically consistent with zero inflation in the unit of account: electronic money. Although the temptation using monetary policy to push the economy above the natural level of output would continue to provide a temptation to raise inflation, in a system with a crawling-peg exchange rate, the desire for seignorage need not by itself create a temptation toward higher inflation.

I love Jeremy Warner’s essay “The UK internet boom that blows apart economic gloom” in the Telegraph. Jeremy makes several important points. One is that accounting for intangible investment, as the latest US GDP revisions do, can affect GDP figures. Here is a deeper issue Jeremy raises:

But even if these changes were to be incorporated, it still wouldn’t do justice to the growth in the digital economy. This is because much internet activity is free, and therefore immeasurable.

Take the traditional music industry, which used to involve, finding, recording and marketing new acts, and then cleaning up through copyrighted CD sales.

For decades, the model worked well — at least for the record producers and a small, elite of popular artists — and made a not insignificant contribution to GDP.

Then along came digital downloads, legal or otherwise. These have destroyed the old music company stranglehold on distribution, and in so doing made previously quite pricey music either far less expensive or completely free.

The pound value of music consumption has declined, and with it the music industry’s contribution to GDP, but the volume of music consumption has risen exponentially.

Much the same thing can be said about newspapers. The traditional business model has been badly undermined by the internet, but news demand and consumption has never been higher. If only we could persuade the blighters to pay, our industry would again be booming….

Prof Brynjolfsson believes that the correct way to measure all this… is via the time people spend immersed in it.

I know Erik Brynjolfsson from his Twitter feed as an excellent commentator on the digital economy.

The growing importance of free goods is one of the many reasons we need to go beyond GDP in accounting for well-being. Looking at the amount of time people spend online to infer value makes a lot of sense. But there are also more radical ways to go beyond GDP, as discussed in “Ori Heffetz: Quantifying Happiness” and “Judging the Nations: Wealth and Happiness are Not Enough.”

For the richest countries, at the technological frontier, human progress has shifted more and more into the realm of intangibles. Services are less tangible than goods; online activities are less tangible than face-to-face services; happiness, job satisfaction and meaning are less tangible than time spent hanging out in cyberspace. If we don’t develop good ways to account for the increasingly intangible dimensions of human progress, we will miss the main story going forward.

It is easy to get upset at the wrong-headedness of one’s political opponents. But sometimes there is a grain of truth to what they have to say. John Stuart Mill had this to say about why progressives and conservatives need each other (from On Liberty, Chapter II “Of the Liberty of Thought and Discussion,” paragraph 36):

In politics, again, it is almost a commonplace, that a party of order or stability, and a party of progress or reform, are both necessary elements of a healthy state of political life; until the one or the other shall have so enlarged its mental grasp as to be a party equally of order and of progress, knowing and distinguishing what is fit to be preserved from what ought to be swept away. Each of these modes of thinking derives its utility from the deficiencies of the other; but it is in a great measure the opposition of the other that keeps each within the limits of reason and sanity. Unless opinions favourable to democracy and to aristocracy, to property and to equality, to co-operation and to competition, to luxury and to abstinence, to sociality and individuality, to liberty and discipline, and all the other standing antagonisms of practical life, are expressed with equal freedom, and enforced and defended with equal talent and energy, there is no chance of both elements obtaining their due; one scale is sure to go up, and the other down. Truth, in the great practical concerns of life, is so much a question of the reconciling and combining of opposites, that very few have minds sufficiently capacious and impartial to make the adjustment with an approach to correctness, and it has to be made by the rough process of a struggle between combatants fighting under hostile banners. On any of the great open questions just enumerated, if either of the two opinions has a better claim than the other, not merely to be tolerated, but to be encouraged and countenanced, it is the one which happens at the particular time and place to be in a minority. That is the opinion which, for the time being, represents the neglected interests, the side of human well-being which is in danger of obtaining less than its share. I am aware that there is not, in this country, any intolerance of differences of opinion on most of these topics. They are adduced to show, by admitted and multiplied examples, the universality of the fact, that only through diversity of opinion is there, in the existing state of human intellect, a chance of fair play to all sides of the truth. When there are persons to be found, who form an exception to the apparent unanimity of the world on any subject, even if the world is in the right, it is always probable that dissentients have something worth hearing to say for themselves, and that truth would lose something by their silence.

I pitched this column to my editors as an Independence Day column. I am proud of our American experiment: attempting government of the people, by the people, and for the people. This column is about the principles behind that American experiment, from an economic perspective.

Thanks to the Wall Street Journal, I saw this passage from Calvin Coolidge’s “Address at the Celebration of the 150th Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence” in Philadelphia, July 5, 1926:

It was not because it was proposed to establish a new nation, but because it was proposed to establish a nation on new principles, that July 4, 1776, has come to be regarded as one of the greatest days in history. Great ideas do not burst upon the world unannounced. They are reached by a gradual development over a length of time usually proportionate to their importance. This is especially true of the principles laid down in the Declaration of Independence. Three very definite propositions were set out in its preamble regarding the nature of mankind and therefore of government. These were the doctrine that all men are created equal, that they are endowed with certain inalienable rights, and that therefore the source of the just powers of government must be derived from the consent of the governed.

If no one is to be accounted as born into a superior station, if there is to be no ruling class, and if all possess rights which can neither be bartered away nor taken from them by any earthly power, it follows as a matter of course that the practical authority of the Government has to rest on the consent of the governed. While these principles were not altogether new in political action, and were very far from new in political speculation, they had never been assembled before and declared in such a combination. But remarkable as this may be, it is not the chief distinction of the Declaration of Independence… .

It was the fact that our Declaration of Independence containing these immortal truths was the political action of a duly authorized and constituted representative public body in its sovereign capacity, supported by the force of general opinion and by the armies of Washington already in the field, which makes it the most important civil document in the world.

I am grateful to JP Koning for agreeing to have this post from his blog Moneyness appear also as a guest post here on supplysideliberal.com. I tweeted “I love your post” and (lightly edited)

Your post “Does the zero lower bound exist thanks to the government’s paper currency monopoly” is very close to my answer in seminars of why private banks can’t undo what I propose central banks do.

For the record, I am not a fan of free banking. I am sympathetic with George Selgin’s claim (in a paper tweeted by David Beckworth) that the early days of central banking and 19th century US financial regulation may have been a step down in monetary stability and financial stability from free banking. But I believe that central banking with an electronic money system and monetary policy along the lines of what I discuss in my column “Optimal Monetary Policy: Could the Next Big Idea Come from the Blogosphere” is superior to free banking. I also give my view of the value of central banking in my post “Let’s Have an End to ‘End the Fed’” (Despite Ron Paul’s success in getting many people to chant “End the Fed” I think abolition of central banks and resumption of free banking is politically less likely–both in the US and in other nations–than the kind of electronic money system I recommend, so there is no strong argument for free banking as a politically easier solution to the zero lower bound problem.)

Many moons ago Matt Yglesias wrote that the “zero lower bound is a pure artifact of the existence of physical cash." In this post I’ll argue that the zero-lower bound, or ZLB, is an artifact of our modern central bank-managed monetary system, and not the existence of cash. In a free banking system in which private banks issue banknotes, competitive forces would force bankers to rapidly find ways to pierce below the ZLB, rendering the bound little more than a fleeting technicality.

What is the zero lower bound? When the economy’s expected rate of return drops significantly below 0%, interest rates charged by banks should follow into negative territory. But if banks set sub-zero interest rates on deposits, everyone will quickly convert them into central bank-issued paper currency. After all, why hold -2% yielding deposits when you can own 0% yielding cash? The inability to set negative interest rates is thezero-lower bound problem.

As I’ll illustrate, the threat of getting stuck at the zero-lower bound would impose such huge losses on private note-issuing banks that bank managers would quickly find creative ways to circumvent the problem. Central bankers, who aren’t beholden to the same financial motivations as private bankers, needn’t pursue these same zero-lower bound innovations with such zeal. This distinction has significant implications for the economy. Insofar as policies designed to remove the ZLB can prevent large macroeconomic distortions, central bankers are more likely to avoid such policies and destabilize the macroeconomy than private banker who, driven by bottom line concerns, will be quick to adopt ZLB-avoiding innovations.

Let’s set up our free banking system. Say that the Fed ceases issuing paper currency and only creates deposits. Into this void, private banks begin issuing their own paper dollar banknotes which can be exchanged for bank deposits at a rate of 1:1. This isn’t such a strange idea—for much of its history, Canada has enjoyed a privately-supplied paper currency. A few years later the economy nosedives and pessimism reigns. Private banks are desperate to decrease deposit rates into negative territory, say -4% or so. After all, banks earn income from the spread between the rate at which they borrow and the rate at which they invest. If, during bad times, a banker is investing at a -2% loss, he or she needs to be borrowing at -4% in order to earn spread income.

Unfortunately for our private banker, the intervening ZLB impedes rates from dropping into negative territory. Any attempt to cut to -4% and bank depositors will flock to convert negative yielding deposits into the bank’s 0% yielding banknotes. Very quickly the bank’s entire liability structure will be comprised of banknotes, a disastrous outcome since a bank that funds itself at 0% while investing at -2% will go broke very quick.

In a negative return world, profit-maximizing private banks would solve their ZLB problem using several strategies:

1. Remove Cash

If banks remove all of their already-issued cash from the economy in return for deposits, the deposits-to-cash escape route will be effectively erased, thereby clearing the way for banks to reduce deposit rates to -4%. One way to do this, courtesy of Bill Woolsey, would be for banks to issue cash with a call feature. Much like a convertible bond allows the bond issuer to force conversion upon investors, bank notes would carry a conversion clause permitting the issuing bank to call in all cash when it desires to reduce deposit rates below zero. [1]

2. Cease conversion into cash

Note-issuing banks might simply close the cash conversion window while allowing existing cash to remain in circulation. This would cut off any rush to convert deposits into cash upon a reduction of deposit rates to -4%. The price of existing cash would jump to a high enough level such that it would be expected to decline at a rate of 4% a year. Conversion stoppages are not without precedent. In 18th century Scotland, banks often issued notes with an option clause that allowed them to cease redemption should a bank run begin.

3. Penalize cash

By penalizing cash, a bank imposes a large enough cost on cash holders so that negative yielding deposits are no longer inferior to cash. There are plenty of ways for a bank to do this. One way is to impose a negative interest rate on cash by requiring cash holders to pay to "update” their bank notes lest they expire. This update fee, which would amount to around 4% a year, would forestall depositors from making a dash for cash when the bank sets deposit rates at -4%. In times past, locally-issued “scrip” like Worgl have had negative interest rates attached to them.

Another creative way for a banker to penalize cash is to impose a capital loss on cash holders. Rather than offering permanent 1:1 cash-to-deposit exchanges, banks might commit themselves to buying back cash (ie. redeeming it) in the future at an ever worsening rate to deposits. As long as the loss imposed on cash amounts to around 4% a year, depositors will not convert their deposits to cash en masse when deposit rates are cut to 4%.

In sum, a number of innovative routes are available for note-issuing banks to let their borrowing costs drop into negative territory. By necessity, private note-issuing banks will adopt these strategies in order to protect their shareholders from the painful effects of mass conversion of cheap deposit funding into relatively costly 0% cash.

That’s all fine and dandy, but our note-issuing mechanism is run by a centralized monopoly, not competing private banks. Because the ZLB is no less binding for central banks than it is for free banks, over the last few years economists and pundits have come up with all sorts of draconian techniques for central banks to escape the ZLB. There have been calls to ban cash, penalize it, and destroy it. At first I was somewhat appalled by these ideas as they seemed to be gross infringements on people’s ability to use cash. Over time I’ve realized that these authoritarian solutions are, somewhat paradoxically, the very same innovations that competing bankers would devise in a free banking world in order to free themselves of the ZLB problem. In other words, we can back out what a monopolist currency issuer *should* be doing to combat the ZLB by imagining what a network of competing banks *would* do. [2]

For instance, in a negative rate world a central bank ban on paper currency would be the equivalent of competing note-issuing banks simultaneously calling in their entire issue of paper currency in order to protect their solvency. If free banks were to penalize cash by redeeming it at ever deteriorating rates, this would be exactly the same strategy that Miles Kimball advocates central banks adopt in order to escape the ZLB.

That central banks have been so slow to evolve strategies for escaping from the ZLB could be due to any number of factors. Central banks aren’t privately owned nor are they disciplined by competition, and central bankers don’t have a mandate to turn a profit. Free banks, burdened by all of these checks, would be forced to rapidly adopt ZLB-escaping strategies or perish.

Further hampering efforts to get central banks like the Fed to innovate solutions to the ZLB is that these efforts might conflict with other goals. Withdrawing cash, penalizing it, or limiting conversion will put an end to, or at least diminish, the circulation of US paper dollars overseas. It might even result in the circulation of some other nation’s 0% yielding currency in the US. But the universal circulation of greenbacks is one of the most potent symbols of US hegemony, real or perceived. In the interests of protecting this symbol, innovations for escaping the ZLB may get short shrift. In a free banking system, these sorts of non-pecuniary motives are unlikely to outweigh the profit and loss calculation that dictates the necessity of adopting such innovations.

So the zero lower bound problem isn’t a problem with cash per se, it’s just a function of monopolistic intransigence. If you really want to short circuit the ZLB, better to devolve the provision of notes to profit-seeking private banks. Until then, hopefully evangelists like Miles Kimball succeed in getting central banks to adopt free banking-style contingency plans in preparation for the next time we experience a crisis that necessitates sub-zero interest rates.

[1] I confess that much of this post was inspired by ideas in two Bill Woolsey posts that I thought deserved wider circulation.

[2] The idea that harsh central bank policies like banning cash or penalizing currency might mimic free banking responses is a recurring theme on this blog. Here, I hypothesized that in a world characterized by free banking, legal tender laws might evolve naturally as the result of market choice. It’s a strange world.

Here is the full text of my 24th Quartz column, that I coauthored with Yichuan Wang, “After crunching Reinhart and Rogoff’s data, we’ve concluded that high debt does not slow growth.” It is now brought home to supplysideliberal.com (and soon to Yichuan's Synthenomics). It was first published on May 29, 2013. Links to all my other columns can be found here. In particular, don’t miss the follow-up column “Examining the Entrails: Is There Any Evidence for an Effect of Debt on Growth in the Reinhart and Rogoff Data?”

If you want to mirror the content of this post on another site, that is possible for a limited time if you read the legal notice at this link and include both a link to the original Quartz column and the following copyright notice:

© May 29, 2013: Miles Kimball and Yichuan Wang, as first published on Quartz. Used by permission according to a temporary nonexclusive license expiring June 30, 2014. All rights reserved.

(Yichuan has agreed to extend permission on the same terms that I do.)

This column had a strong response. I have included the text of my companion column, with links to many of the responses after the text of the column itself. (For the comments attached to that companion post, you will still have to go to the original posting.) Other followup posts can be found in my “Short-Run Fiscal Policy” sub-blog.

Leaving aside monetary policy, the textbook Keynesian remedy for recession is to increase government spending or cut taxes. The obvious problem with that is that higher government spending and lower taxes tend to put the government deeper in debt. So the announcement on April 15, 2013 by University of Massachusetts at Amherst economists Thomas Herndon, Michael Ash and Robert Pollin that Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff had made a mistake in their analysis claiming that debt leads to lower economic growth has been big news. Remarkably for a story so wonkish, the tale of Reinhart and Rogoff’s errors even made it onto the Colbert Report. Six weeks later, discussions of Herndon, Ash and Pollin’s challenge to Reinhart and Rogoff continue in earnest in the economics blogosphere, in the Wall Street Journal, and in the New York Times.

In defending the main conclusions of their work, while conceding some errors, Reinhart and Rogoff point out that even after the errors are corrected, there is a substantial negative correlation between debt levels and economic growth. That is a fair description of what Herndon, Ash and Pollin find, as discussed in an earlier Quartz column, “An Economist’s Mea Culpa: I relied on Reinhardt and Rogoff.” But, as mentioned there, and as Reinhart and Rogoff point out in their response to Herndon, Ash and Pollin, there is a key remaining issue of what causes what. It is well known among economists that low growth leads to extra debt because tax revenues go down and spending goes up in a recession. But does debt also cause low growth in a vicious cycle? That is the question.

We wanted to see for ourselves what Reinhart and Rogoff’s data could say about whether high national debt seems to cause low growth. In particular, we wanted to separate the effect of low growth in causing higher debt from any effect of higher debt in causing low growth. There is no way to do this perfectly. But we wanted to make the attempt. We had one key difference in our approach from many of the other analyses of Reinhart and Rogoff’s data: we decided to focus only on long-run effects. This is a way to avoid getting confused by the effects of business cycles such as the Great Recession that we are still recovering from. But one limitation of focusing on long-run effects is that it might leave out one of the more obvious problems with debt: the bond markets might at any time refuse to continue lending except at punitively high interest rates, causing debt crises like that have been faced by Greece, Ireland, and Cyprus, and to a lesser degree Spain and Italy. So far, debt crises like this have been rare for countries that have borrowed in their own currency, but are a serious danger for countries that borrow in a foreign currency or share a currency with many other countries in the euro zone.

Here is what we did to focus on long-run effects: to avoid being confused by business-cycle effects, we looked at the relationship between national debt and growth in the period of time from five to 10 years later. In their paper “Debt Overhangs, Past and Present,” Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff, along with Vincent Reinhart, emphasize that most episodes of high national debt last a long time. That means that if high debt really causes low growth in a slow, corrosive way, we should be able to see high debt now associated with low growth far into the future for the simple reason that high debt now tends to be associated with high debt for quite some time into the future.

Here is the bottom line. Based on economic theory, it would be surprising indeed if high levels of national debt didn’t have at least some slow, corrosive negative effect on economic growth. And we still worry about the effects of debt. But the two of us could not find even a shred of evidence in the Reinhart and Rogoff data for a negative effect of government debt on growth.

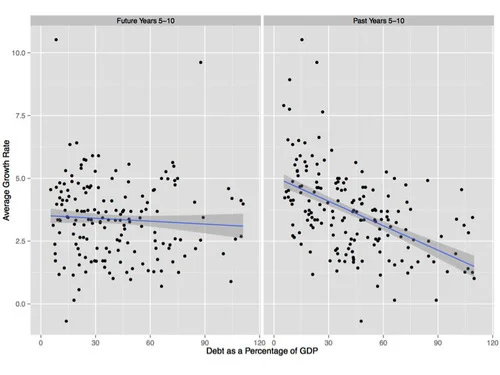

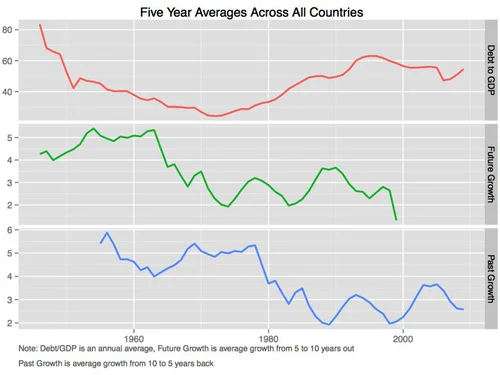

The graphs at the top show show our first take at analyzing the Reinhardt and Rogoff data. This first take seemed to indicate a large effect of low economic growth in the past in raising debt combined with a smaller, but still very important effect of high debt in lowering later economic growth. On the right panel of the graph above, you can see the strong downward slope that indicates a strong correlation between low growth rates in the period from ten years ago to five years ago with more debt, suggesting that low growth in the past causes high debt. On the left panel of the graph above, you can see the mild downward slope that indicates a weaker correlation between debt and lower growth in the period from five years later to ten years later, suggesting that debt might have some negative effect on growth in the long run. In order to avoid overstating the amount of data available, these graphs have only one dot for each five-year period in the data set. If our further analysis had confirmed these results, we were prepared to argue that the evidence suggested a serious worry about the effects of debt on growth. But the story the graphs above seem to tell dissolves on closer examination.

Given the strong effect past low growth seemed to have on debt, we felt that we needed to take into account the effect of past economic growth rates on debt more carefully when trying to tease out the effects in the other direction, of debt on later growth. Economists often use a technique called multiple regression analysis (or “ordinary least squares”) to take into account the effect of one thing when looking at the effect of something else. Here we are doing something that is quite close both in spirit and the numbers it generates for our analysis, but allows us to use graphs to show what is going on a little better.

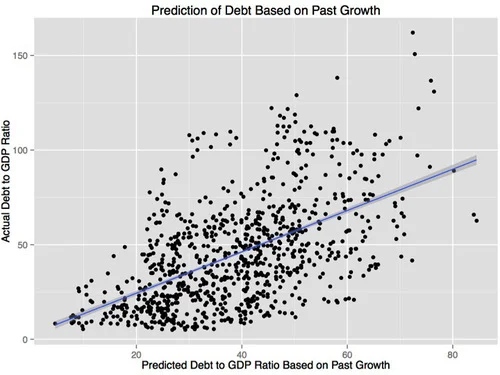

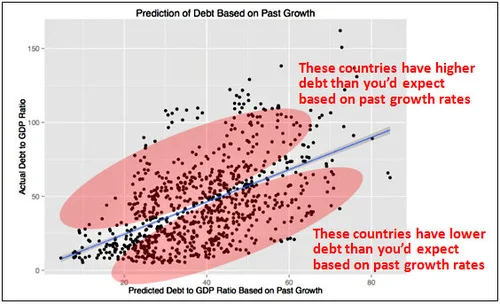

The effects of low economic growth in the past may not all come from business cycle effects. It is possible that there are political effects as well, in which a slowly growing pie to be divided makes it harder for different political factions to agree, resulting in deficits. Low growth in the past may also be a sign that a government is incompetent or dysfunctional in some other way that also causes high debt. So the way we took into account the effects of economic growth in the past on debt—and the effects on debt of the level of government competence that past growth may signify—was to look at what level of debt could be predicted by knowing the rates of economic growth from the past year, and in the three-year periods from 10 to 7 years ago, 7 to 4 years ago and 4 to 1 years ago. The graph below, labeled “Prediction of Debt Based on Past Growth” shows that knowing these various economic growth rates over the past 10 years helps a lot in predicting how high the ratio of national debt to GDP will be on a year by year basis. (Doing things on a year by year basis gives the best prediction, but means the graph has five times as many dots as the other scatter plots.) The “Prediction of Debt Based on Past Growth” graph shows that some countries, at some times, have debt above what one would expect based on past growth and some countries have debt below what one would expect based on past growth. If higher debt causes lower growth, then national debt beyond what could be predicted by past economic growth should be bad for future growth.

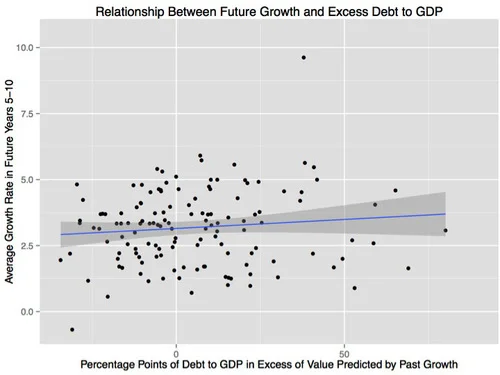

Our next graph below, labeled “Relationship Between Future Growth and Excess Debt to GDP” shows the relationship between a debt to GDP ratio beyond what would be predicted by past growth and economic growth 5 to 10 years later. Here there is no downward slope at all. In fact there is a small upward slope. This was surprising enough that we asked others we knew to see what they found when trying our basic approach. They bear no responsibility for our interpretation of the analysis here, but Owen Zidar, an economics graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, and Daniel Weagley, graduate student in finance at the University of Michigan were generous enough to analyze the data from our angle to help alert us if they found we were dramatically off course and to suggest various ways to handle details. (In addition, Yu She, a student in the master’s of applied economics program at the University of Michigan proofread our computer code.) We have no doubt that someone could use a slightly different data set or tweak the analysis enough to make the small upward slope into a small downward slope. But the fact that we got a small upward slope so easily (on our first try with this approach of controlling for past growth more carefully) means that there is no robust evidence in the Reinhart and Rogoff data set for a negative long-run effect of debt on future growth once the effects of past growth on debt are taken into account. (We still get an upward slope when we do things on a year-by-year basis instead of looking at non-overlapping five-year growth periods.)

Daniel Weagley raised a very interesting issue that the very slight upward slope shown for the “Relationship Between Future Growth and Excess Debt to GDP” is composed of two different kinds of evidence. Times when countries in the data set, on average, have higher debt than would be predicted tend to be associated with higher growth in the period from five to 10 years later. But at any time, countries that have debt that is unexpectedly high not only compared to their own past growth, but also compared to the unexpected debt of other countries at that time, do indeed tend to have lower growth five to 10 years later. It is only speculating, but this is what one might expect if the main mechanism for long-run effects of debt on growth is more of the short-run effect we mentioned above: the danger that the “bond market vigilantes” will start demanding high interest rates. It is hard for the bond market vigilantes to take their money out of all government bonds everywhere in the world, so having debt that looks high compared to other countries at any given time might be what matters most.

Our view is that evidence from trends in the average level of debt around the world over time are just as instructive as evidence from the cross-national evidence from debt in one country being higher than in other countries at a given time. Our last graph (just above) shows what the evidence from trends in average levels over time looks like. High debt levels in the late 1940s and the 1950s were followed five to 10 years later with relatively high growth. Low debt levels in the 1960s and 1970s were followed five to 10 years later by relatively low growth. High debt levels in the 1980s and 1990s were followed five to 10 years later by relatively high growth. If anyone can come up with a good argument for why this evidence from trends in the average levels over time should be dismissed, then only the cross-national evidence about debt in one country compared to another would remain, which by itself makes debt look bad for growth. But we argue that there is not enough justification to say that special occurrences each year make the evidence from trends in the average levels over time worthless. (Technically, we don’t think it is appropriate to use “year fixed effects” to soak up and throw away evidence from those trends over time in the average level of debt around the world.)

We don’t want anyone to take away the message that high levels of national debt are a matter of no concern. As discussed in “Why Austerity Budgets Won’t Save Your Economy,” the big problem with debt is that the only ways to avoid paying it back or paying interest on it forever are national bankruptcy or hyper-inflation. And unless the borrowed money is spent in ways that foster economic growth in a big way, paying it back or paying interest on it forever will mean future pain in the form of higher taxes or lower spending.

There is very little evidence that spending borrowed money on conventional Keynesian stimulus—spent in the ways dictated by what has become normal politics in the US, Europe and Japan—(or the kinds of tax cuts typically proposed) can stimulate the economy enough to avoid having to raise taxes or cut spending in the future to pay the debt back. There are three main ways to use debt to increase growth enough to avoid having to raise taxes or cut spending later:

1. Spending on national investments that have a very high return, such as in scientific research, fixing roads or bridges that have been sorely neglected.

2. Using government support to catalyze private borrowing by firms and households, such as government support for student loans, and temporary investment tax credits or Federal Lines of Credit to households used as a stimulus measure.

3. Issuing debt to create a sovereign wealth fund—that is, putting the money into the corporate stock and bond markets instead of spending it, as discussed in “Why the US needs its own sovereign wealth fund.” For anyone who thinks government debt is important as a form of collateral for private firms (see “How a US Sovereign Wealth Fund Can Alleviate a Scarcity of Safe Assets”), this is the way to get those benefits of debt, while earning more interest and dividends for tax payers than the extra debt costs. And a sovereign wealth fund (like breaking through the zero lower bound with electronic money) makes the tilt of governments toward short-term financing caused by current quantitative easing policies unnecessary.

But even if debt is used in ways that do require higher taxes or lower spending in the future, it may sometimes be worth it. If a country has its own currency, and borrows using appropriate long-term debt (so it only has to refinance a small fraction of the debt each year) the danger from bond market vigilantes can be kept to a minimum. And other than the danger from bond market vigilantes, we find no persuasive evidence from Reinhart and Rogoff’s data set to worry about anything but the higher future taxes or lower future spending needed to pay for that long-term debt. We look forward to further evidence and further thinking on the effects of debt. But our bottom line from this analysis, and the thinking we have been able to articulate above, is this: Done carefully, debt is not damning. Debt is just debt.

The title chosen by our editor is too strong, but not so much so that I objected to it; the title of this post is more accurate.

Yichuan only recently finished his first year at the University of Michigan. Yichuan’s blog is Synthenomics. You can see Yichuan on Twitter here. Let me say already that from reading Yichuan’s blog and working with him on this column, I know enough to strongly recommend Yichuan for admission to any Ph.D. program in economics in the world. He should finish has bachelor’s degree first, though.

I genuinely went into our analysis expecting to find evidence that high debt does cause low growth, though of course, to a much smaller extent than low growth causes high debt. I was fully prepared to argue (first to Yichuan and then to the world) that even a statistically insignificant negative effect of debt on growth that was plausibly causal had to be taken seriously from a Bayesian perspective. Our analysis set out the minimal hurdles I felt had to be jumped over to convince me that there was some solid evidence that high debt causes low growth. A key jump was not completed. That shifted my views.

I hope others will try to replicate our findings. That should let me rest easier.

From a theoretical point of view, I am especially intrigued by the possibility that any effect on growth from refinancing difficulties might depend on a country’s debt to GDP ratio compared to that of other countries. What I find remarkable is that despite the likely negative effect of debt on growth from refinancing difficulties, we found no overall negative effect of debt on growth. It is as if there is some other, positive effect of debt on growth to the extent a country’s relative debt position stays the same. Besides the obvious, but uncommonly realized, possibility of very wisely deployed deficit spending, I can think of two intriguing mechanisms that could generate such an effect. First, from a supply-side point of view, lower tax rates now could make growth look higher now, perhaps at the expense of growth at some future date when taxes have to be raised to pay off the debt, with interest. Second, government debt increases the supply of liquid (and often relatively safe) assets in the economy that can serve as good collateral. Any such effect could be achieved without creating a need for higher future taxes or lower future spending by investing the money raised in corporate stocks and bonds through a sovereign wealth fund.

I have thought a little about why borrowing in a currency one can print unilaterally makes such a difference to the reactions of the bond market to debt. One might think that the danger of repudiating the implied real debt repayment promises by inflation would mean the risks to bondholders for debt in one’s own currency would be almost the same as for debt in a foreign currency or a shared currency like the euro. But it is one thing to fear actual disappointing real repayment spread over some time and another thing to have to fear that the fear of other bondholders will cause a sudden inability of a government to make the next payment at all.

Note: Brad Delong writes:

Miles Kimball and Yichuan Wang confirm Arin Dube: Guest Post: Reinhart/Rogoff and Growth in a Time Before Debt | Next New Deal:

As I tweeted,

.@delong undersells our results. I would have read Arin Dube’s results alone as saying high debt *does* slow growth.

*Of course* low growth causes debt in a big way. But we need to know if high debt causes low growth, too. No ev it does!

In tweeting this, I mean,if I were convinced Arin Dube’s left graph were causal, the left graph seems to suggest that higher debt causes low growth in a very important way, though of course not in as big a way as slow growth causes higher debt. If it were causal, the left graph suggests it is the first 30% on the debt to GDP ratio that has the biggest effect on growth, not any 90% threshold. Yichuan and I are saying that the seeming effect of the first 30% on the debt to GDP ratio could be due in important measure to the effect of growth on debt, plus some serial correlation in growth rates. The nonlinearity could come from the fact that it takes quite high growth rates to keep a country from have some significant amounts of debt—as indicated by Arin Dube’s right graph, which is more likely to be primarily causal.

By the way, I should say that Yichuan and I had seen the Rortybomb piece on Arin Dube’s analysis, but we were not satisfied with it. But I want to give credit for this as a starting place for Yichuan and me in our thinking.

Brad Delong’s Reply: Thanks to Brad DeLong for posting the note above as part of his post “DeLong Smackdown Watch: Miles Kimball Says That Kimball and Wang is Much Stronger than Dube.”

Brad replies:

From my perspective, I tend to say that of course high debt causes low growth—if high debt makes people fearful, and leads to low equity valuations and high interest rates. The question is: what happens in the case of high debt when it comes accompanied by low interest rates and high equity values, whether on its own or via financial repression?

Thus I find Kimball and Wang’s results a little too strong on the high-debt-doesn’t-matter side for me to be entirely comfortable…

My Thoughts about What Brad Says in the Quote Just Above: As I noted above, my reaction is to what we Yichuan and I found is similar to Brad’s. There must be a negative effective of debt on growth through the bond vigilante channel, as Yichuan and I emphasize in our interpretation. For example, in our final paragraph, Yichuan and I write:

…other than the danger from bond market vigilantes, we find no persuasive evidence from Reinhart and Rogoff’s data set to worry about anything but the higher future taxes or lower future spending needed to pay for that long-term debt.

The surprise is the pattern that when countries around the world shifted toward higher debt than would be predicted by past growth, that later growth turned out to be somewhat higher than after countries around the world shifted to lower debt. It may be possible to explain why that evidence from trends in the average level of debt around the world over time should be dismissed, but if not, we should try to understand those time series patterns. It is hard to get definitive answers from the relatively small amount of evidence in macroeconomic time series, or even macroeconomic panels across countries, but given the importance of the issues, I think it is worth pondering the meaning of what limited evidence there is from trends in the average level of debt around the world over time. That is particularly true since in the current crisis, many people have, recommended precisely the kind of worldwide increase deficit spending—and therefore debt levels—that this limited evidence speaks to.

I am perfectly comfortable with the idea that the evidence from trends in the average level of debt around the world over time is limited enough so theoretical reasoning that shifts our priors could overwhelm the signal from the data. But I want to see that theoretical reasoning. And I would like to get reactions to my theoretical speculations above, about (1) supply-side benefits of lower taxes that reverse in sign in the future when the debt is paid for and (2) liquidity effects of government debt (which may also have a price later because of financial cycle dynamics).

Matt Yglesias’s Reaction: On MoneyBox, you can see Matthew Yglesias’s piece “After Running the Numbers Carefully There’s No Evidence that High Debt Levels Cause Slow Growth.” As I tweeted:

Don’t miss this excellent piece by @mattyglesias about my column with @yichuanw on debt and growth. Matt gets it.

In the preamble of my post bringing the full text of “An Economist’s Mea Culpa: I Relied on Reihnart and Rogoff" home to supplysideliberal.com, I write:

In terms of what Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff should have done that they didn’t do, “Be very careful to double-check for mistakes” is obvious. But on consideration, I also felt dismayed that they didn’t do a bit more analysis on their data early on to make a rudimentary attempt to answer the question of causality. I wouldn’t have said it quite as strongly as Matthew Yglesias, but the sentiment is basically the same.

Paul Krugman’s Reaction: On his blog, Paul Krugman characterized our findings this way:

There is pretty good evidence that the relationship is not, in fact, causal, that low growth mainly causes high debt rather than the other way around.

Kevin Drum’s Reaction: On the Mother Jones blog, Kevin Drum gives a good take on our findings in his post “Debt Doesn’t Cause Low Growth. Low Growth Causes Low Growth.” He notices that we are not fans of debt. I like his version of one of our graphs:

Mark Gongloff’s Reaction: On Huffington Post, Mark Gongloff’s“Reinhart and Rogoff’s Pro-Austerity Research Now Even More Thoroughly Debunked by Studies” writes:

…University of Michigan economics professor Miles Kimball and University of Michigan undergraduate student Yichuan Wang write that they have crunched Reinhart and Rogoff’s data and found “not even a shred of evidence" that high debt levels lead to slower economic growth.

And a new paper by University of Massachusetts professor Arindrajit Dube finds evidence that Reinhart and Rogoff had the relationship between growth and debt backwards: Slow growth appears to cause higher debt, if anything….

This contradicts the conclusion of Reinhart and Rogoff’s 2010 paper, “Growth in a Time of Debt,” which has been used to justify austerity programs around the world. In that paper, and in many other papers, op-ed pieces and congressional testimony over the years, Reinhart And Rogoff have warned that high debt slows down growth, making it a huge problem to be dealt with immediately. The human costs of this error have been enormous….

At the same time, they have tried to distance themselves a bit from the chicken-and-egg problem of whether debt causes slow growth, or vice-versa. "The frontier question for research is the issue of causality,“ [Reinhart and Rogoff] said in their lengthy New York Times piece responding to Herndon. It looks like they should have thought a little harder about that frontier question three years ago.

There is an accompanying video by Zach Carter.

Paul Andrews Raises the Issue of Selection Bias: The most important response to our column that I have seen so far is Paul Andrews’s post "None the Wiser After Reinhart, Rogoff, et al.” This is the kind of response we were hoping for when we wrote “We look forward to further evidence and further thinking on the effects of debt.” Paul trenchantly points out the potential importance of selection bias:

What has not been highlighted though is that the Reinhart and Rogoff correlation as it stands now is potentially massively understated. Why? Due to selection bias, and the lack of a proper treatment of the nastiest effects of high debt: debt defaults and currency crises.

The Reinhart and Rogoff correlation is potentially artificially low due to selection bias. The core of their study focuses on 20 or so of the most healthy economies the world has ever seen. A random sampling of all economies would produce a more realistic correlation. Even this would entail a significant selection bias as there is likely to be a high correlation between countries who default on their debt and countries who fail to keep proper statistics.

Furthermore Reinhart and Rogoff’s study does not contain adjustments for debt defaults or currency crises. Any examples of debt defaults just show in the data as reductions in debt. So, if a country ran up massive debt, could’t pay it back, and defaulted, no problem! Debt goes to a lower figure, the ruinous effects of the run-up in debt is ignored. Any low growth ensuing from the default doesn’t look like it was caused by debt, because the debt no longer exists!

I think this issue needs to be taken very seriously. It would be a great public service for someone to put together the needed data set.

Note that Paul Andrews views are in line with our interpretation of our findings. Let me repeat our interpretation, with added emphasis:

…other than the danger from bond market vigilantes, we find no persuasive evidence from Reinhart and Rogoff’s data set to worry about anything but the higher future taxes or lower future spending needed to pay for that long-term debt.

Of course, it is disruptive to have a national bankruptcy. And national bankruptcies are more likely to happen at high levels of debt than low levels of debt (though other things matter as well, such as the efficiency of a nation’s tax system). And the fear by bondholders of a national bankruptcy can raise interest rates on government bonds in a way that can be very costly for a country. The key question for which the existing Reinhart and Rogoff data set is reasonably appropriate is the question of whether an advanced country has anything to fear from debt even if, for that particular country, no one ever seriously doubts that country will continue to pay on its debts.

In my sermons “UU Visions”“ and "So You Want to Save the World,” I say that a vision of how things should be is the starting place for trying to get there. Star Trek, along with entertainment, provides one such vision. The following is an excerpt from Jessica Tozer’s post “The Continuing Scientific Relevance of SciFi” written for the Armed with Science blog.

By the time Star Trek aired its first episode in 1966, Gene Roddenberry, the creator of Star Trek, was already a seasoned military veteran…. He flew planes in World War II, totaling 89 missions until he was honorably discharged at the rank of captain in 1945. During that time he saw people of all types in the military, pulling together for the sake of the mission, patriotism and each other. It was this social foundation upon which he built his future military premise.

“It speaks to some basic human needs that there is a tomorrow, that it’s not all going to be over in a big flash and a bomb, that the human race is improving, that we have things to be proud of as humans. No, ancient astronauts did not build the pyramids. Human beings built them because they’re clever and they work hard. Star Trek is about those things.” – Gene Roddenberry

… Roddenberry believed that the future would have evolved as much in science and technology as it would in social reform (miniskirts and beehives not withstanding).

“If man is to survive, he will have learned to take a delight in the essential differences between men and between cultures. He will learn that differences in ideas and attitudes are a delight, part of life’s exciting variety, not something to fear.” — Gene Roddenberry

Nichelle Nichols, who played Lt. Uhura (in TOS), often recalls the story about the time she was thinking of quitting Star Trek to return to Broadway, and how it was Martin Luther King, Jr. who talked her out of it. A fan of Star Trek, MLK Jr. mentioned to Nichelle that her show was one of the few he and his wife would allow their children to watch, and that she was a symbol for reform and change….

So she stayed. I mean, who could say no to that?

As a result, she would go on to film the episode “Plato’s Stepchildren”, the first example of a scripted inter-racial kiss between a white man and black woman on American television.

How’s that for social change?

It was a vision of successful racial integration. Men, women of all races working together as equals….

Whoopi Goldberg asked to have her role as Guinan on Star Trek TNG. She has been quoted as saying that she too, loved Star Trek as a kid, and that the show was the first indication that “black people make it to the future”. Geordi is blind and he flies a spaceship. Worf is an alien race that was once an enemy, serving proudly on the bridge of the Enterprise. Data is an android. I could go on and on.