Twitter Round Table on Federal Lines of Credit and Monetary Policy →

Be warned: this Twitter discussion is highly technical.

A Partisan Nonpartisan Blog: Cutting Through Confusion Since 2012

Be warned: this Twitter discussion is highly technical.

The Guardian had a feature “Dear George Osborne, it’s time for Plan B say top economists: Seven leading economists on what Chancellor George Osborne should do to revive the ailing UK economy.” That inspired this post with my advice to the United Kingdom on the Independent’s blog, which I reprint here. Thanks to Ben Chu, Jonathan Portes and David Blanchflower for encouragement. (The links below open in the same window, so use the back button to get back.)

Dear Chancellor of the Exchequer,

Since I am an American citizen, it might be argued that I have no business giving advice to the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. But the economic troubles we face are worldwide and I believe are amenable to a common solution if any major nation will show the way with a new tool of macroeconomic stabilization that has fallen into our hands.

The basic problem is that fear is causing many households and firms in the private sector who could spend to cut back on their spending, while others who would be glad to spend more cannot get access to credit. Much of the advice from economists has been for governments to spend more. But even governments that have had good credit ratings and have made some attempt to increase spending have felt limited by the addition to national debt that would result from the amount of extra spending that might be needed to restore economic health. For example, in his excellent Atlantic article, “Obama Explained,” James Fallows wrote:

If keeping the economy growing was so central for Obama, why was the initial stimulus “only” $800 billion? “The case is quite compelling that if more fiscal and monetary expansion had been done at the beginning, things would have been better,” Lawrence Summers told me late last year. “That is my reading of the economic evidence. My understanding of the judgment of political experts is that it wasn’t feasible to do.” Rahm Emanuel told me that within a month of Obama’s election, but still another month before he took office, “the respectable range for how much stimulus you would need jumped from $400 billion to $800 billion.” In retrospect it should have been larger—but, Emanuel says, “in the Congress and the opinion pages, the line between ‘prudent’ and ‘crazy spendthrift’ was $800 billion. A dollar less, and you were a statesman. A dollar more, you were irresponsible.”

What is needed—mainly for genuine economic reasons, but also for political reasons—is a way to provide a large amount of stimulus without adding too much to the national debt. In my new academic paper “Getting the Biggest Bang for the Buck in Fiscal Policy,” and on my blog, I propose and discuss a tool for macroeconomic stabilization that can do exactly that. The proposal, which I call “National Lines of Credit,” (or “Federal Lines of Credit” in the US case) is to send government-issued credit cards to all taxpayers that have a substantial line of credit attached—say £2,000 per adult, or £4,000 pounds per couple. The interest rate would be relatively favorable, say 6%, with a 10-year repayment period so that most of the repayment would happen after the economy is back on its feet again. But the government would insist on eventual repayment, except for the very-long-term unemployed or disabled. Insisting on repayment would make the ultimate addition to the national debt small compared to the stimulus provided by these National Lines of Credit.

The paper provides many more details of how National Lines of Credit might work than I should try to include here, but I should mention that a key detail is requiring each household not only to pay down its debt, but also to build up a reserve of savings after the economy has fully recovered. That reserve of savings would be there to help deal with any more distant future crisis. Also, let me say that, depending on the exactly how they are implemented, National Lines of Credit are either distributionally neutral or tend to favor the poor; by contrast, the Bank of England has estimated that its program of buying gilts (which might also be necessary) has had immediate benefits tilted toward the wealthy.

Perhaps just as important as the stimulus provided by a program of National Lines of Credit would be the value of demonstrating that this kind of approach works, if it does, or gaining a greater understanding of the workings of the economy if it doesn’t. The best existing evidence- historical evidence based on the decision to allow World War 1 veterans in the U.S. to borrow against their veterans’ bonuses – suggests that the stimulus effect can be substantial. But the politics of many nations will require more evidence before National Lines of Credit can be implemented there. (Many nations in the Eurozone need a program of National Lines of Credit even more than the United Kingdom does.) Some nation must blaze the trail. If the United Kingdom is willing to take the risk of going first in trying out this new stimulus measure, and it works, it will not only have helped to solve its own economic troubles, it will have earned the gratitude of the world, in a small but still significant echo of the way in which it earned the gratitude of the world by standing against Hitler.

Miles Kimball is an economics professor at the University of Michigan who studies business cycles and the effects of risk on household consumption. He blogs about economics and politics at supplysideliberal.com.

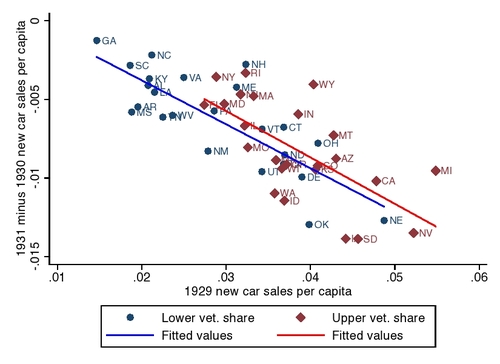

Guest blogger Joshua Hausman’s graph of the change in car sales in each state between 1930 and 1931, as a function of car sales in 1929, broken into those states with below-median fraction of veterans in the population (blue) and above-median fraction of veterans in the population (red). The fitted lines do not impose equal slopes.

The graph excludes the District of Columbia (DC), since it is a large outlier. Including DC strengthens the case for an effect of being allowed to borrow against the veteran’s bonus on auto sales: DC had a high share of veterans and was the only state to see auto sales actually increase from 1930 to 1931.

This is a guest post by Joshua Hausman. Joshua is a graduate student at Berkeley on the job market this Fall.

Perhaps the best historical analogies to Miles’s Federal Lines of Credit Proposal are 1931 and 1936 policy changes that gave World War I veterans early access to a promised 1945 bonus payment. In 1924, Congress passed a bill promising veterans large payments in 1945. When the depression came, veterans’ groups lobbied congress for immediate payment. Congress partially acquiesced in 1931, giving veterans the ability to borrow up to 50 percent of the value of their promised bonus beginning on February 27. (Prior to this, veterans could take loans of roughly 22.5 percent of their bonus.) For the typical veteran, this meant being able to borrow about $500. For comparison, in 1931 per capita personal income was $517. The loans carried an interest rate of 4.5 percent, but interest did not have to be paid annually. Rather, the amount of the loan plus interest would be deducted from what was due the veteran in 1945. In fact, the interest rate was lowered to 3.5 percent in 1932, and then forgiven entirely in 1936. But there is no reason to think that this was expected at the time.

Despite their ability to take loans, veterans continued to demand immediate cash payment of the entire, non-discounted, value of their bonus. Tens of thousands of veterans camped in Washington, DC from May to July 1932 to lobby for immediate payment. Finally, in 1936, congress granted their wish, giving veterans the choice of taking their bonus in cash or leaving it with the government where it would earn 3 percent interest until 1945. Whereas the 1931 policy change was a pure loan program, the 1936 policy had elements of both a loan and a transfer, since it gave veterans access to the same amount of cash in 1936 that they otherwise would have gotten in 1945, and since part of the 1936 bill forgave interest on earlier loans. A rough calculation suggests that of the typical bonus amount of $550 received in 1936, roughly half was an increase in veterans’ permanent income, while the other half was essentially a loan.

My ongoing work focuses on evaluating the 1936 bonus, both because it was quantitatively much larger than the 1931 loan payments, and because there is a household consumption survey and a survey of veterans themselves that makes it possible to evaluate the policy’s effects in detail. But the 1931 program is a better analogy for Miles’ Federal Line of Credit proposal. Thus in the rest of this blog post I consider what evidence there is on the 1931 program.

No single source of evidence is definitive, but several pieces of evidence suggest that loans to veterans boosted consumption in 1931. First, it is significant that veterans eagerly took advantage of the loan program. In the four months following the policy change (March to June 1931), veterans took 2.06 million loans worth an aggregate $796 million, or one percent of GDP. Since there were 3.7 million World War I veterans, these figures suggest that a majority quickly took advantage of the loan program (that is, unless many veterans took multiple loans). Given the 4.5 percent interest rate, and the lack of many attractive investment opportunities in the 1931 economy, it only made sense for veterans to take these loans to consume or to pay down high interest rate debt.

Other evidence points to veterans using some of the money on consumption rather than using it entirely to pay down debt. First, there is an uptick in department store sales amidst what is otherwise a steady downward trend. Seasonally adjusted sales rose 2.9 percent in April, the month when veterans took out the most loans. Since the proportion of veterans in the population varied significantly across states, it is also possible to relate changes in new car sales in a state to the number of veterans in the state, and thus measure the effect of the loan program. Uncovering whether or not there was such a relationship is tricky since the loan program was small compared to the other shocks hitting the economy. In particular, states with more veterans tended to be states in the west, and these states had higher car sales in 1929. In turn, states that had higher car sales in 1929 tended to see larger declines in sales during the Depression. A way to see both the relationship to 1929 sales, and the effect of veteran share is to graph the 1930-31 change in car sales per capita against the level of 1929 car sales. This is done in the figure at the top. The blue dots are states in the lower half of the veteran share distribution (i.e. states with fewer than 2.9 veterans per 100 people) and the red dots are states in the top half of the veteran share distribution. The lines are the fitted values for each set of points. The graphical evidence is hardly definitive, but it is at least consistent with the fact that conditional on pre-depression conditions, being in the top half of the veteran share distribution led to higher auto sales in 1931.

Finally, narrative sources provide some indication of what people at the time thought veterans were doing with the money. News stories are also consistent with veterans spending the money on cars. For example, the Los Angeles Times wrote on March 22, 1931: “The opinion has been ventured that the bonus readjustment would have a beneficial effect upon the motor trade and that a liberal amount of this money would find its way into the pockets of the automobile dealer. The prediction is becoming a fact to a greater extent than was at first anticipated."

Newspapers also reported veterans spending on other consumer items. The New York Times wrote on April 5, 1931: "That the payment of the soldiers’ bonus has definitely increase purchases of merchandise, particularly men’s wear, was the opinion yesterday of Julian Goldman, head of the Julian Goldman Stores, Inc., which sell goods on the instalment [sic] plan. Mr. Goldman recently returned from an extended trip through the country and reported that managers of his own stores and other merchants attributed a substantial increase in sales to the veterans spending their loan money.” The article goes on to also say that veterans were using their loans to pay back installment debt on previous clothing purchases.

2012 is not 1931 and a trial of Federal Lines of Credit today would provide much better evidence of its effects. But the 1931 experience is at least encouraging. The balance of evidence suggests that the loan program was popular and that it increased consumption relative to what it otherwise would have been. Of course, the economy still saw large absolute declines in consumption and output in 1931, since the loan program was tiny compared to the negative shocks hitting the economy.

Information on the the bonus legislation and the number and dollar amount of loans is taken from the 1931 Annual Report of the Administrator of Veterans’ Affairs, in particular, p. 42; data on seasonally adjusted department store sales are from

http://www.nber.org/databases/macrohistory/rectdata/06/m06002a.dat.

Data on veterans per capita in each state are from the 5% IPUMS sample from the 1930 Census; data on new car sales by state are from the industry trade publication Automotive Industries, data for 1929 sales is from the February 22, 1930 issue, p. 267, for 1930 from the February 28, 1931 issue p. 309, and for 1931 from the February 27, 1932 issue p. 294.

This is long–2 hours and 22 minutes–so you should only try to listen to this if you are a bear for punishment. But I thought some of you might be interested.

Mark Thoma has a new post “Starving the Beast in Recessions” that links to his article in the Fiscal Times: “How GOP Lawmakers have the Fed Over a Barrel.” Mark’s post backs up the concern I expressed in “Preventing Recession-Fighting from Becoming a Political Football” that traditional stimulative fiscal policy–tax cuts or increases in goverment spending–entangles recession fighting in political disputes about the size and scope of government. In that post, I wrote:

By avoiding big changes in taxes or spending, I hope my Federal Lines of Credit proposal can help to depoliticize stabilization policy.

“Preventing Recession-Fighting from Becoming a Political Football” is a difficult post. For more accessible posts on Federal Lines of Credit, go to my second post “Getting a Bigger Bang for the Buck in Fiscal Policy” or to “My First Radio Interview on Federal Lines of Credit.” I plan to do a set of index posts for my sidebar giving links to all of my posts by topic area soon. At that point, the index post on “Short-Run Fiscal Policy” will link to all of my posts on Federal Lines of Credit.

Mike Konczal has a recent post “Four Issues with Miles Kimball’s ‘Federal Lines of Credit’ Proposal," announced by this tweet:

Mike’s tweet is the only way I can get a working link to his post. This link may work at some point in the future. Here is Mike’s description of my proposal:

What’s the idea? Under normal fiscal stimulus policy in a recession, we often send people checks so that they’ll spend money and boost aggregate demand. Let’s say we are going to, as a result of this current recession, send everyone $200. Kimball writes, "What if instead of giving each taxpayer a $200 tax rebate, each taxpayer is mailed a government-issued credit card with a $2,000 line of credit?” What’s the advantage here, especially over, say, giving people $2,000? “[B]ecause taxpayers have to pay back whatever they borrow in their monthly withholding taxes, the cost to the government in the end—and therefore the ultimate addition to the national debt—should be smaller. Since the main thing holding back the size of fiscal stimulus in our current situation has been concerns about adding to the national debt, getting more stimulus per dollar added to the national debt is getting more bang for the buck.”

Mike has some praise and four Roman numerals worth of objections. I promised a detailed answer. Other than the comment threads after each post, this is only the second time I have had a serious online criticism of one of my posts, and I will try to accomplish the same sort of thing I tried to accomplish in my answer to the first serious criticism I received from Stephen Williamson: to answer the criticism point by point while at the same time making some important points worth making even aside from this dustup with Mike. The main point I want to make uses the phrases “fiscal policy” and "stabilization policy,“ which can be given the following rough-and-ready definition:

Fiscal policy: government policy on taxing and spending

Stabilization policy: loosely, recession-fighting (in times of recession) and inflation-fighting (in times of boom).

More precise definitions of stabilization policy inevitably involve the details of exactly what should be done and when, which are sometimes under dispute; this definition will serve for now. Here is the main point I want to make in this post:

Long-run fiscal policy is unavoidably political, since it involves the tradeoff between the benefits of redistribution and the benefits of low tax rates, but stabilization policy can and should be kept relatively apolitical. The politicization of stabilization policy in the last few years is an unfortunate, and fundamentally unnecessary, turn of events.

By avoiding big changes in taxes or spending, I hope my Federal Lines of Credit proposal can help to depoliticize stabilization policy.

The reason a discussion of the politicization of stabilization policy belongs in a reply to Mike Konczal is that my simple summary of his objections to my Federal Lines of Credit proposal of government-issued credit cards to stimulate the economy is that my proposal does not do enough to redistribute toward the poor. Now my views on redistribution are no secret. As I said in my first post, "What is a Supply-Side Liberal,” redistribution is good. In my post “Rich, Poor and Middle-Class,” I made a stronger statement, focusing on helping the poor, which is the important part of redistribution:

I am deeply concerned about the poor, because they are truly suffering, even with what safety net exists. Helping them is one of our highest ethical obligations.

The other type of redistribution, which is more controversial (because the redistributive benefit is smaller and the economic efficiency cost is higher) is taxing the rich in order to help the middle class. Given the fact that redistribution needs to be financed by taxes or by deficit spending, Republicans and Democrats differ substantially on how much redistribution they think should be done of either type. As a result, the political fights over long-run taxing and spending policy are often bitter. My fervent hope is to find ways to avoid having the the blood that is spilled over long-run taxing and spending policy from infecting short-run stabilization policy, which by rights should be less controversial especially in a recession, since recessions are bad for almost everyone. It is a little harder to say that inflation is bad for almost everyone, since inflation benefits debtors at the expense of creditors, but few people on either side of the political divide advocate high inflation as a way to wipe out debts, and most of the other effects of inflation higher than a few percent per year are bad for everyone.

What has made stabilization policy a political football in the last few years is the fact that the Federal Reserve is maxed out on its favorite recession-fighting tool of lowering short-term interest rates. Because currency effectively earns an interest rate of zero, no one is willing to lend money at an interest rate much below zero, so zero is about as low as the Fed can go. In my answer to the first serious criticism I received from Stephen Williamson, I argue that the Fed can still do a lot more to stimulate the economy even when the nominal interest rate is already down to zero, but the Fed has been reluctant to use unfamiliar tools to the full extent possible. And the size of the necessary changes to the Fed’s balance sheet are enough to scare many people (in a way that I argue is unwarranted in my third, and to this date, most-viewed post “Balance Sheet Monetary Policy.”) Indeed, the Fed has become a political target not only because of its sadly necessary role in saving the economy by bailing out big banks, but also because even the Fed’s half-measures have involved big enough changes in the Fed’s balance sheet to scare many people.

Besides monetary policy, the traditional remedies in stabilization policy have to do with taxing and spending. In particular, the traditional remedies for a recession other than monetary stimulus are tax cuts and spending increases. It is easy to see the problem. Since taxes and spending are also the center of the political debate about long-run policy, any use of taxes or spending to fight recessions arouses justifiable suspicion that the other side will use recession-fighting as an excuse to advance its long-run agenda: for Republicans, lowering taxes in the long run, for Democrats, increasing the amount of redistribution in the long run.

By contrast, since monetary policy does not touch on what in recent history are the core political debates about taxing and spending, for at least the 30 years from mid 1988 to mid 2008 (when the financial crisis and the Great Recession threw things for a loop) political controversies over monetary policy have been relatively esoteric–not the sorts of things that move the average voter in either party.

In crafting my Federal Lines of Credit proposal, one of my key objectives was to find a new way of fighting recessions that, like monetary policy in normal times, would be fully acceptable to both political parties. The U.S. economy and the world economy are in trouble, and it is important that politics not get in the way of what needs to be done. So I am pleased to have Mike Konczal say of my proposal “This has gotten interest across the political spectrum.” The proposal itself is described in my second post “Getting the Biggest Bang for the Buck in Fiscal Policy,” and my recent post “Bill Greider on Federal Lines of Credit: 'A New Way to Recharge the Economy’” is a good way to catch up on the discussion about Federal Lines of Credit since then.

Now let me turn to Mike’s four issues:

I. Isn’t deleveraging the issue? Is this a solution looking for a problem? From the policy description, you’d think that a big is credit access holding the economy in check.

But taking a look at the latest Federal Reserve credit market growth by sector, you can see that credit demand has collapsed in this recession.

I actually think that credit access has gone down. For example it is a lot harder getting home-equity lines of credit these days than it used to be, even for those whose houses are worth a lot more than their mortgages. But Mike is right that many people are scared enough about the economy that they are trying to pay down their credit card debt. The key point here is that what makes sense from an individual point of view in time of recession–reducing household spending–makes things worse for all of us by reducing the amount of business that firms get and therefore how many workers feel they can hire. So to help out the macroeconomic situation, we want people to lean toward spending more than they otherwise would. Giving every taxpayer access to a federal line of credit at a reasonable interest rate and reasonable terms (say 6%, paid off over 10 years) would cause at least some people to spend more, which is what we want in order to stimulate the economy.

II. This policy is like giving a Rorschach test to a vigilante. No, not that vigilante. I mean the bond vigilantes.

Mike’s point here is that, although in the long-run, people will have to pay back the money they borrowed from the government on their Federal Lines of Credit, the government is out the money in the meantime, and this might add to the official deficit and national debt numbers. So if the folks in the bond market are not smart enough to look past the surface of the deficit and national debt numbers, they might cause long-term interest rates to go up. Here, my answer is simple: the folks in the bond markets are very, very smart. They know the difference between the government being out money forever (as it would be if it used a tax rebate) and the government making loans that will be repaid, say, 90% of the time. As evidence that the “bond vigilantes” look at more than the official debt to GDP ratios, take a look at this list of debt to GDP ratios. (I am using the International Monetary Fund’s numbers from this table, rounded off to the nearest percent. If there are more recent numbers, I am confident they will show the same thing.) Here are the examples that make my point:

Spain: 69%

Germany: 82%

United States: 103%

Japan: 230%

It is right to worry about the future, but currently, Spain is in trouble with the bond vigilantes, while the world is eager to lend money to Germany, the United States and Japan. (See my post “What to Do When the World Desperately Wants to Lend Us Money” about what this eagerness of the world to lend to the U.S. means for U.S. policy from a wonkish point of view that ignores political difficulties.) The reason Spain is in trouble with the bond vigilantes is that the Spanish government is seen to be on the hook for the much of the debts of Spanish banks; this bank debt that may become Spanish government debt sometime in the future does not show up in the official debt to GDP figures, but the bond vigilantes know all about it. On the other end, one reason that the bond vigilantes are still willing to lend money to Japan at low interest rates is that they know Japanese households do a lot of saving and don’t like to put their money abroad, so a lot of that saving makes its ways into Japanese government bonds, either directly or indirectly.

III. This policy will involve trying to get blood from a turnip. I very much distrust it when economists waive away bankruptcy protection. Especially for experimental, controversial debts that have never been tried in known human history.

As the paper admits, this is a machine for generating adverse selection, as the people most likely to use it are people whose credit access is cut due to the recession. High-risk users will likely transfer their balances from higher rate credit cards to their FOLC (either explicitly or implicitly over time if barred) - transferring a nice chunk of credit risk from the financial industry to taxpayers.

It’s also not clear what happens a few years later when consumers start to pay off the FOLC. Could that trigger another recession, especially if the creditor (the United States) doesn’t increase spending to compensate?

The issue isn’t whether or not the government will be able to collect these debts at some point. It has a long time-horizon, the ability to jail debtors and use bail to pay debts, the ability to seize income, old-age pensions and a wide variety of income, and the more general ability to deploy its monopoly on violence. The question is whether this will be smoother, easier, and more predictable than just collecting the money in taxes. We have a really smooth system for collecting taxes, one at least as good as whatever debt collection agencies are out there. If that is the case, there’s no reason to believe that this will satisfy the bond vigilantes or bring down our debt-to-GDP ratio in a more satisfactory way.

Mike actually raises several issues here. Let me be clear that I am not proposing jailing debtors! I am imagining something like the current system we have for student loans directly from the Federal government. These loans cannot be wiped away by bankruptcy, but no one is jailing former students who can’t pay what they owe on their student loans. When I supposed above that (including interest–I am thinking in present values) only 90% of the money would be repaid, the other 10% is money that the government ultimately gives up on trying to collect because some people can’t pay. To avoid any possible abuses, I think it would be a good idea to specify in the law authorizing Federal Lines of Credit that people’s debts under the program could never be sold to an outside collection agency: only official government employees would be allowed to make collection efforts. Worry about a political firestorm would prevent the government from doing the kinds of things the private collection agencies sometimes do. Almost all repayment would be through payroll deduction from people who are drawing a paycheck, with perhaps some repayment through small deductions from government transfers people receive when those government transfers are above a minimum level.

Is an expected loan-loss rate of 10% too much? Then it is easy to modify the program to reduce the loan-loss rate without reducing its effectiveness in recession-fighting by allowing those with higher incomes to borrow more and restricting the size of the lines of credit for those with lower incomes. For those worried about issues with Federal Lines of Credit like those Mike is raising, I strongly recommend reading my relatively accessible academic paper on the proposal: “Getting the Biggest Bang for the Buck in Fiscal Policy.” But now I am going to give you fair warning about what “relatively accessible” means by quoting the somewhat recondite way that I make this point in the paper:

One of the main factors in the level of de facto loan losses would be the extent to which the size of the lines of credit goes up with income. Despite the reduction in additional aggregate demand per headline size of the program that might be occasioned by conditioning on income, de facto loan losses would probably decline by a greater proportion, meaning that conditioning on income might improve the ratio of extra consumption to budgetary cost. Certainly, having the line of credit go up with income might reduce the level of implicit redistribution, which is a consideration I will not try to address here.

To translate, if we give rich taxpayers bigger lines of credit than poor taxpayers, we will probably get even more bang-for-the-buck from the program–in the sense that there will be more stimulus for each dollar ultimately added to the national debt after most repayment has happened.

I will confess that the only reason I didn’t make this kind of dependence of the size of the line of credit on income the benchmark version of the proposal is that I wanted to sneak in a little income redistribution into the program. But if next year we have a Republican Congress and a Republican President (now trading at a 30% probability on Intrade), stimulating the economy is important enough that it is still a very good thing to do the Federal Line of Credit program with less redistribution than I had in the benchmark version of the proposal, which gives the same-size line of credit to each taxpayer. On the other hand, if next year we have a Democratic Congress and a Democratic President (now trading at a 7.5% probability on Intrade), stimulating the economy is important enough that it is still a very good thing to do the Federal Line of Credit program with lines of credit of the same size not only for every taxpayer but also for non taxpaying adults and to let the debts be extinguished in bankruptcy. Federal Lines of Credit would still give us more bang-for-the-buck than other types of fiscal stimulus that a Democratic Congress and Democratic President might turn to, and regardless of what happens politically, the United States government does have to worry about the bond vigilantes down the road whenever it adds to the national debt in a long-run way. In what I consider the most likely case of divided government, where out of the presidency, the Senate and the House of Representatives, each party holds at least one (now trading at a 62.5% probability on Intrade if one includes the 4.5% probability of “other,” which presumably covers the case when the control of one house of congress depends on how the few independents vote), something in between–perhaps not too far from my benchmark proposal–seems to me what would be politically feasible.

In the passage I quoted from Mike labeled as his issue III, he also worries about whether the repayment of the loans would cause a recession later on. I have thought that stretching out repayment over 10 years would be enough to avoid this problem, but I view this an issue for the experts. If, as I prefer (see my post “Bill Greider on Federal Lines of Credit: 'A New Way to Recharge the Economy’”), the Federal Reserve determines many of the details of the Federal Lines of Credit Program, I trust the staff of the Federal Reserve Board and the Federal Reserve Banks to come up with a better answer on the appropriate length of time for loan repayment than either Mike or I could.

Finally, we come to Mike’s fourth and last issue, which motivated my discussion above about the value of separating long-run fiscal issues from short-run stabilization policy, so that recession-fighting doesn’t become a political football. What Mike writes to explain his fourth issue is long enough that I will intersperse some comments along the way. From here on, everything in block quotes reproduces Mike’s words.

IV.Since we’ve very quickly gotten to the idea that we’ll need to jettison legal protections under bankruptcy for this plan to work, it is important to emphasize that this policy is the opposite of social insurance.

As I said above, I am not advocating jailing debtors. I don’t see the fact that student loans are not expunged in bankruptcy as a massive social injustice that causes huge problems; if it is, it would meant that it is a travesty that the Obama administration is only proposing having private student loans wiped away by bankruptcy while leaving public student loans from the government untouched by bankruptcy. I am sure some people think that, and would not be surprised if that is Mike’s view, but I don’t think the average voter would take that view, nor do I criticize the Obama administration for not being willing to go far enough and have all student loans expunged in bankruptcy.

I don’t see a macroeconomic difference between the government borrowing 3 percent of GDP and giving it away and collecting it through taxes later versus the government borrowing 3 percent of GDP, loaning it to individuals, and collecting it later through debt collectors except in the efficiency and the distribution.

This passage is well-designed to underemphasize the fact that the way in which, say, “3 percent of GDP” is given away is redistributive. Indeed, to the extent that asking everyone to pay the same amount is regressive, giving everyone the same amount as in my benchmark proposal has to count as anti-regressive. There is no question that giving away 3 percent of GDP and collecting it later through progressive taxes would bemore redistributive. Overall, my program is fairly neutral as far as redistribution goes, though as I confessed, I snuck a little redistribution into my benchmark proposal because those with higher incomes would likely repay a bigger fraction of the borrowed money than those with higher incomes.

The distributional consequences of this proposal aren’t addressed, but they are quite radical. Normally taxes in this country are progressive. Some people call for a flat tax. This proposal would be the equivalent of the most regressive taxation, a head tax. And it also undermines the whole idea of social insurance.

Mike seems to be claiming that the Federal Lines of Credit program overall is regressive. I just don’t see this. Is the government’s student loan program regressive? Just because a program could be made more redistributive than it is, does not mean that on the whole it is regressive.

Let’s assume the poorest would be the people most likely to use this to boost or maintain their spending. I think that’s largely fair - certainly the top 10 percent are less likely to use this (they’ll prefer to use high-end credit cards that give them money back). This means that as the bottom 50 percent of Americans borrow and pay it off themselves, they would bear all the burden for macroeconomic stability through fiscal policy. Given that the top 1 percent captured 93 percent of the income growth in the first year of this recovery, that’s a pretty major transfer of wealth. One nice thing about tax policy, especially progressive tax policy, is that those who benefit the most from the economy provide more of the resources. This would be the opposite of that, especially in the context of a “"relatively-quickly-phased-in austerity program.”

Let me say quickly that my mention of “austerity” was in the European context, where paying what the bond market demands without a full-scale bailout from a reluctant Germany requires austerity. I made no mention of “austerity” for the U.S., nor do I think “austerity” will be necessary for the U.S., if we follow the kinds of proposals I recommend.

Going back up to the top of this block quote from Mike, again, saying that the bottom 50 percent of Americans “would bear all the burden for macroeconomic stability” ignores the fact that they were able to borrow and use the money when they really needed it during hard economic times. The only way in which this could be a burden is if loaning money on relatively favorable terms (again, say at 6% for 10 years) is an unkind temptation to people who have trouble stopping themselves from spending more now than they should. I worried about this, which is why I proposed that, by the time the next recession rolls around, we have National Rainy Day Accounts set up that allow people to spend in recessions or during documentable personal financial emergencies money that they have saved up previously. Now requiring someone to save money for later emergencies they might face, and encouraging them to spend some of that money in a national emergency such as a future recession may indeed be a burden. But it is hard for me to see how both proposals–letting people borrow on favorable terms from Federal Lines of Credit and requiring people to save in National Rainy Day Accounts–can be a burden. The only way that allowing people to borrow on favorable terms can be a burden is if they have trouble saving as much as they should, in which case setting up a structure to help them save will help them out. And Mike agrees that “There’s a lot to like about the proposal [Federal Lines of Credit], particularly how it could be used after a recession is over to provide high-quality government services to the under-banked or those who find financial services yet another way in which it is expensive to be poor …" On a more negative note, Mike continues as follows in the text of his fourth issue:

Efficiency is also relevant - as the economy grows, the debt-to-GDP ratio declines, making the debt easier to bear. The most likely borrowers under FOLC [sic], the bottom 50 percent, have seen stagnant or declining wages overall, especially in recessions. A growing economy would keep their wages from falling in the medium term, but this is still a problematic issue - their income is not more likely to grow to balance out the payment burdens than if we did this at a national level, like normal tax policy.

The policy also ignores social insurance’s role in macroeconomic stability, and that’s insurance against low incomes. Making sure incomes don’t fall below a certain threshold when times are tough makes good macroeconomic sense and also happens to be quite humane. This is not that. As friend-of-the-blog JW Mason said, when discussing this proposal, the FOLC [sic] is like "if your fire insurance simply consisted of a right to borrow money to rebuild your house if it burned down.”

Here again, I take Mike’s point that it would be easy to do more redistribution than the modest amount of redistribution in the Federal Lines of Credit proposal as I lay it out. But I view redistribution as the province of long-run fiscal policy (in the broadest sense). Trying to use recession-fighting as a way to also do more redistribution is a recipe for making recession-fighting a political football. If recession-fighting becomes a political football, as it has to an unfortunate extent in the last few years, the recession (or the long tail of unemployment that follows what are officially called “recessions”) wins. And bad economic times are especially hard on those at the bottom of the income distribution. So they can least afford to have recession-fighting become a political football. My hope is that Federal Lines of Credit will make it possible to stimulate the economy when necessary in a way that avoids major changes in taxing and spending that would set off alarms for one or another of the two warring parties in the political debate.

Karl Smith has a recent post “Why is the US Government Still Collecting Taxes?: Should Lambs Lay Down with Lions Edition” arguing that we should be dramatically reducing tax collection because interest rates on government bonds are so low that, after correcting for inflation, every dollar in the national debt is shrinking over time. Karl’s post follows up on Ezra Klein’s post “The world desperately wants to lend us money,” and my grad school professor Larry Summers’s post “It’s time for governments to borrow more money.” Ezra and Larry want the government to pay ahead on things it is going to buy anyway and make other productive investments.

Larry, coming from his experience as Secretary of the Treasury makes a strong argument that the U.S. government should be borrowing long rather than short, in order to lock in amazingly low interest rates on long-term government bonds. Since the U.S. government’s position in relation to the bonds it has issued depends on what the Fed does as well as what the Treasury does, this argues against the Fed buying long-term government bonds when Larry’s argument says we should be selling long-term government bonds on net. Larry has convinced me by what he writes in “It’s time for governments to borrow more money.” The Fed should not be buying long-term government bonds.

But for the sake of stimulating the economy, the Fed needs to be buying large quantities of some type of asset. This is not just my view, implicit as a possibility in my post “Balance Sheet Monetary Policy: A Primer,” but the the official view of the Fed itself, since even the mostly stay-the-course policy the Fed announced at its last FOMC monetary policy making meeting involves buying large quantities of assets. (“Large” is less than “massive.”) So it is unfortunate that the legal authority of the Fed to buy assets is limited to a relatively narrow range of assets. See Mike Konczal’s interview with my undergraduate classmate Joseph Gagnon on the legal constraints the Fed faces. Short of buying foreign assets or otherwise going outside the Fed’s comfort zone, that probably means that the Fed should be buying mortgage-backed securities such as those issued by Fannie Mae. In general, when it uses balance-sheet monetary policy (what the press calls “quantitative easing”), the Fed should lean towards buying assets that have a high interest rate.

It is important to note that many of the objections to more vigorous use of balance sheet monetary policy in the U.S. are really objections to buying long-term Treasury bonds, not objections to buying other assets. Anytime you see an argument against balance sheet monetary policy, check whether it is an objection to buying any kind of asset or only to buying long-term Treasury bonds. And sometimes there are objections to buying Treasury bonds and other objections to buying mortgage-backed securities that even combined do not apply to other assets. So I wish the Fed had the kind of authority the Bank of Japan has to buy a wide range of assets, including commercial paper (CP), corporate bonds, exchange traded funds (ETF’s), and real estate investment trusts (REIT’s). I got this list of assets from the Bank of Japan’s own website on the range of assets it is buying. See also my post on how the Bank of Japan should use this authority quantitatively: “Future Heroes of Humanity and Heroes of Japan.”

Given the low interest rates the U.S. government is facing, even aside from stimulating the economy it should be spending more–mostly on things it would buy later anyway and other productive investments. On stimulating the economy, my proposal of Federal Lines of Credit is gaining some traction: you can see my posts on what Brad DeLong and Joshua Hausman and Bill Greider have to say recently, as well as what Reihan Salam said early on. In what I write myself on Federal Lines of Credit, including the academic paper “Getting the Biggest Bang for the Buck in Fiscal Policy” that I flag at the sidebar, I emphasize the importance of not ultimately adding too much to the national debt as it will stand, say ten years from now. This is actually consistent with saying that the government shouldbe spending money now on things the government is going to spend money on sooner or later anyway, regardless of which party is in power, such as maintenance of military assets and stores, and the government should be spending money now on things that will add to the productivity of the economy so much that they will generate more than enough tax revenue to pay for themselves.

The existence of government investment that has this property of generating more tax revenue in the future than needed to make the payments on the money the government borrowed to make the investment is the spending counterpart to being on the wrong side of the Laffer curve so that you could cut taxes and get more revenue. I am not sure how many government investments meet this stringent test, but if any do, everyone should be in favor of them, regardless of their political viewpoint. To have that statement be true, I am assuming that the investment is something noncontroversial that everyone would be glad to have for free (not something like a national stem-cell laboratory). The reason everyone should be in favor of such a self-financing investment is that the American taxpayers would be getting a better deal than “free.”

Now, a government investment being self-financing in this sense is quite hard because for this, it is not good enough to have benefits great enough to pay for the direct cost to the government (the naive cost-benefit test). The extra payments to the U.S. Treasury alone (typically a minority of the total benefits) must be enough to pay for the investment. If on net the U.S. Treasury is out money at the end of the day for the sake of other benefits, then the dollars from the U.S. Treasury have to be counted as costing more than dollar for dollar since each dollar of government spending typically has a deadweight loss from tax distortion on top of it. (See for example Diewert, Lawrence and Thompson’s paper on this. There is a good discussion in this paper accessible to anyone even before the first equation.) As long as the U.S. Treasury is out money at the end of the day, the sophisticated cost-benefit test can easily flip from thumbs up to thumbs down depending on how big the tax distortions are–and economists don’t agree on that. I am on the side of believing there are relatively large tax distortions. (See my first post, “What is a Supply-Side Liberal,” which is also now at the sidebar.)

Interest rates won’t stay low forever, and the U.S. government, unlike the government of the United Kingdom of Britain and Northern Ireland, does not sell consols that would lock in a low interest rate forever (though maybe it should in the current environment). Moreover, extra debt probably raises the interest rate on existing debt. So the cost of extra debt is higher than the interest rate itself. (This is the monopoly problem from Economics 101: the U.S. government is a monopolist in the original issuance of its own debt, and so has to consider the effect of issuing more debt on the price and interest rates of existing debt.)

The last words in this post are is in response to Karl Smith’s post, which motivated the lamb and lion illustration. (Karl’s “lamb” is the U.S. government, while the “lion” is the bond traders in the financial markets). If, as I think they will, interest rates will some day go above not only inflation, but above the long-run growth rate of the economy as a whole (which matters among other things because it is the growth rate of the tax base), and the government cannot lock in a lower rate forever using consols, then any money the government borrows will cost us sometime in the future. The low interest rates now prevailing will make government borrowing now cost less in the future, but it won’t make the cost zero. Doesn’t that mean that we should do all our taxing later, when the amounts of money will have shrunk rather than now? It would if the cost of getting an extra dollar of tax revenue were constant over time. But a basic result from public finance is that the cost of getting an extra dollar of tax revenue goes up as you try to get more and more tax revenue as a fraction of GDP. That is why I was so confident in my post “Avoiding Fiscal Armageddon” that there is some limit of government spending as a fraction of GDP that we shouldn’t go beyond, even if that limit is higher than the 50% that I used as an example (and as a reasonable representation of my own judgment given my current knowledge.) Given the pressures on the government budget that I talk about in “Avoiding Fiscal Armageddon,” I will be shocked if tax rates are not higher in the future than they are now. So if the cost of getting an extra dollar of tax revenue goes up with the rates you already have, then there is an argument for moving toward raising tax rates at times such as now when tax rates are low compared to what they will be later. This “tax smoothing” argument counterbalances the implications of current lower interest rates, which favor lower taxes now. On balance, given the low interest rates the U.S. government is paying, tax rates should certainly be lower now than we expect them to be in the future, but there is a question of how much.

Why is this called a “tax smoothing” argument? The reason is that raising tax rates when you think tax rates will be higher in the future–or following similar logic, lowering tax rates when you think tax rates will be lower in the future–tends to equalize tax rates now relative to expected tax rates in the future. I have not personally done any research on tax smoothing, but I learned about it from proofreading all of the math in Greg Mankiw’s paper “The Optimal Collection of Seigniorage: Theory and Evidence,” when I was Greg’s research assistant in graduate school, and I have heard more about it from my colleagues at the University of Michigan.

In my second post, “Getting the Biggest Bang for the Buck with Fiscal Policy,” I wrote about my interview with Bill Greider and promised I would let you know when his article came out. Bill Greider is national affairs correspondent for The Nation, and the author of Secrets of the Temple, a history of the Federal Reserve. And at the link under the picture, you can see a short clip of Bill Greider talking to Bill Moyers that will give you some of the experience I had in meeting Bill Greider. Bill’s article is out now, on The Nation’s blog. Here it is. The simple summary is that Bill is pushing my proposal of Federal Lines of Credit as hard as he can, while connecting it to some of his own longstanding interests.

Let me say what I hope is obvious: this blog and my relatively accessible academic paper “Getting the Biggest Bang for the Buck in Fiscal Policy” are authoritative about what I am proposing in relation to Federal Lines of Credit, not Bill Greider’s post. (See also the Powerpoint file for my presentation at the Federal Reserve Board.) But though Bill’s nuances are very different from mine, the only serious issue I have with his post is that Bill makes it sound as if I want to have a less independent Fed. Far from it! What I actually said in my paper “Getting the Biggest Bang for the Buck in Fiscal Policy” is this:

The lack of legal authority for central banks to issue national lines of credit is not set in stone. Indeed, for the sake of speed in reacting to threatened recessions, it could be quite valuable to have legislation setting out many of the details of national lines of credit but then authorizing the central bank to choose the timing and (up to some limit) the magnitude of issuance. Even when the Fed funds rate or its equivalent is far from its zero lower bound at the beginning of a recession, the effects of monetary policy take place with a significant lag (partly because of the time it takes to adjust investment plans), while there is reason to think that consumption could be stimulated quickly through the issuance of national lines of credit. Reflecting the fact that national lines of credit lie between traditional monetary and traditional fiscal policy, the rest of the government would still have a role both in establishing the magnitude of this authority and perhaps in mandating the issuance of additional lines of credit over the central bank’s objection (with the overruled central bank free to use contractionary monetary policy for a countervailing effect on aggregate demand).

Let me explain that “National Lines of Credit” is just another name for “Federal Lines of Credit” that I use in the paper because that name of the program works better in Europe, where it is most likely to be done by individual nations rather than by the Eurozone as a whole.

What I want is amore powerful, but still fully independent Fed. In particular, I want a Fed that is in charge of aspects of policy that are in between traditional fiscal policy and traditional monetary policy and a Fed permitted by law to purchase a wider range of assets, as the Bank of Japan is. (See my post “Future Heroes of Humanity and Heroes of Japan.”) I believe that the Fed is doing less stimulus than it otherwise would because it is not fully comfortable with balance sheet monetary policy on the scale required. (See my post “Trillions and Trillions: Getting Used to Balance Sheet Monetary Policy.”) In other words, I am claiming that if the Fed had been given the authority by Congress to use Federal Lines of Credit as a tool, it would have done more stimulus, and the economy would be in better shape. (On my respect for the Bernanke Fed, see the lead-in to my first list of “save-the-world” posts.)

Two things I hope that Bill mentions if he returns to this topic in the future, as I hope he does, are

I hope to have many more interactions with Bill Greider in the future, both in cyberspace and in person.

Mike Sax writes about my exchange with Karl Smith, starting with my post “Why Taxes are Bad,” Karl Smith’s reply “Miles Kimball on Taxing the Rich” and finally my post “Rich, Poor and Middle-Class.” He has at least three different lines of questions. In this post I want to answer two that might be summarized as “But what about the demand side, as a source of revenue and a source of jobs?” Here is what Mike says:

One more point: Implicit is the idea that rich are the "job creators.“ It’s not wholly true that the Occupy Wall Street presumed that most wealthy people are rich through personal chicanery. Much of their indignation is directed to what they see as systemic injustice-I for one do believe that capitalism is the most efficient and potentially most just allocator of resources, though I’m skeptical of too much laissez-faire. What I see in Supply Side analysis is no recognition that 70% of GDP is consumer demand. So who is exactly the job creators?

http://useconomy.about.com/od/grossdomesticproduct/f/GDP_Components.htm

If there’s no money in people’s pockets there’s no demand and no job creation. Again, my position is a "Demand Sider” I’d like to find ways to reduce the demand side taxes-the taxes that the poor and middle income have to pay, from high payroll taxes, to the litany of state sales taxes, and fees-traffic fees, meters, indeed, insurance. As I suggested in my first reply to Miles nothing gets my goat more than this Cato canard that’s repeated ad nauseum that “45% of Americans pay no tax.”

Even the wino on a park bench pays tax every time he gets his hands on demon rum.

Does Miles recognize the distortions that come from the demand side of income-the taxes that the nonrich pay? Again, I poise these questions to Miles as I appreciate his contributions to the debate. Hopefully he understands the spirit that I poise these questions. I’ve certainly changed my opinion some on the “progressive consumption tax”-not enough to take the scare quotes away yet, of course!-and am willing to be persuaded on supply side issues.

Mike is absolutely right that the poor and middle class pay substantial amounts of sales taxes and taxes on earnings such as Social Security taxes. When people want to argue that the tax system is unfair to the rich, they often skew things by only talking about the income tax. But a key point to make here is that almost all countries that devote a higher fraction of GDP to government spending than the U.S. tax the middle-class a lot through a national sales tax or a value added tax (VAT) which is a lot like a sales tax except that it is harder to evade because much of the tax is collected from companies long before the good gets to the final consumer. The European model, in particular, is to tax the middle-class heavily in order to give benefits to the middle class. I believe that the resultant tax distortions are why so many Europeans work many fewer hours per year than Americans. They used to work roughly the same amount as Americans when they had lower tax rates. (These are facts that Ed Prescott has made much of.)

Why not just tax the rich to pay for benefits for the middle class? The basic problem is that there aren’t enough rich people. I found this video by Tyler Durden etertaining and revealing on this topic. I can’t verify what he says exactly, though I think the basic point is right. You have to include at least the upper middle class in your tax in a big way, or you can’t get enough extra revenue to do a big expansion of social programs.

So the “demand side” is a big source of potential revenue, if by that you mean some kind of sales tax of VAT tax. But to get a lot of revenue, you have to include people who don’t think of themselves as rich, and whose acquaintances might not even think of them as rich. Maybe we should do it anyway, but it won’t feel like what people imagine a tax on the rich would feel. Here I remember Senator Russell B. Long’s parody:

“Don’t tax you, don’t tax me, tax that man behind the tree.”

There just aren’t enough “men behind the tree” who don’t seem like you or me.

What about the demand side as a source of jobs? (This is a more typical meaning of “demand-side.”) Here, my answer is that, despite the floundering of policy makers lately, it is fundamentally easy to get enough aggregate demand. On this, just click the sidebar link on the June+ 2012 table of contents and look at all the posts on monetary policy and short-run fiscal policy, together with the recent post on evidence that Federal Lines of Credit should work: “Brad DeLong and Joshua Hausman on Federal Lines of Credit.” (My post “Dissertation Topic 1: Federal Lines of Credit (FLOC’s)” is also useful, but is pretty heavy.) The bottom line is that monetary policy can provide plenty of aggregate demand, and if the Fed won’t do what it takes, we can use Federal Lines of Credit and the change in the timing of Federal payments to the states for Medicare that I talk about in “Leading States in the Fiscal Two-Step” to get enough aggregate demand without adding too much to the national debt. So, you wouldn’t know it from the news or from big chunks of discussion in the blogosphere, but getting enough aggregate demand is the easy problem. Raising aggregate supply while getting the revenue we need is the hard problem.

World War I veterans in 1920, who later had the chance to borrow against their bonus

Brad Delong not only praises Federal Lines of Credit, he managed to identify some empirical evidence that suggests they should indeed be more powerful than tax rebates! Here is what he says:

The interesting thing is that we have done this before. In 1931 and 1936 the Congress (over the objections of President Hoover in the first case and President Roosevelt in the second) gave World War I veterans the option to borrow against the WWI Veterans’ Bonus that they were going to be paid in the future:

Then Brad cites a study of letting veterans back then borrow against their bonus by Berkeley graduate student Joshua Hausman. Here is Brad’s summary of the results:

Because the bonus was paid to veterans and only veterans, Josh has substantial cross-section identification off of the different proportions of veterans in the several states. The (preliminary) figures and regression results are, to my eye, awesome: a cash-flow multiplier that looks to be 0.8 or so.

Federal Lines of Credit are an extraordinarily effective recession-fighting policy when mental accounts or liquidity constraints are important, and it looks as though they were very important in the 1930s.

Here is a download of the Powerpoint file for the presentation I gave at the Federal Reserve Board on May 14, 2012, as recounted in my second post “Getting the Biggest Bang for the Buck in Fiscal Policy.” It had an element of discussing Stefan Nagel’s longer presentation immediately before, a presentation based in part on his paper with Ulrike Malmendier “Depression Babies: Do Macroeconomic Experiences Affect Risk-Taking,” but ranges beyond that to a wider discussion. My most important idea in this presentation is Federal Lines of Credit (FLOC’s) as a way to provide fiscal stimulus without adding much to the national debt–an idea laid out in full detail in my academic paper about Federal Lines of Credit: “Getting the Biggest Bang for the Buck in Fiscal Policy.” As academic papers go, this one is quite accessible to non-economists.

A Depiction of “The Miracle of the Seagulls” from Mormon History

Miles, I greatly enjoy your blog. I am 3rd year econ phd with a burgeoning interest in the impact of fiscal policy and government expenditure during recessions. Much of the literature simply attempts to calculate a jobs or GDP multiplier, but there are many other impacts of fiscal policy. What are important costs and benefits of fiscal policy that you feel are understudied? Who are the winners and losers from stimulus expenditure? I have a particular interest in firm and worker outcomes. Thanks! – markcurti

The answer here is easy for me. There has been no formal modeling of my Federal Lines of Credit proposal in my second post

“Getting the Biggest Bang for the Buck in Fiscal Policy.”

This is a serious proposal–and in my view an extremely important proposal–that deserves formal modeling, but I am not going to do that formal modeling myself. (Why don’t I do this myself? See on my CV at the sidebar the number of other research projects I have in progress–many more than the number of my publications!) So it definitely counts as understudied. Here again is the link to the full article that I have submitted to a professional economics journal laying out the proposal in some detail. I even have an NBER Working Paper by the same name that you can cite, though I recommend reading the one I link to rather than the NBER Working Paper.

When I say “formal modeling,” I am thinking this is one place where a Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) model would be quite appropriate in order to get some sense of likely magnitudes. Since analyzing Federal Lines of Credit requires modeling borrowing constraints and heterogeneity, as well as modeling sticky prices so that aggregate demand matters for output, there would be plenty of chances to develop and show off technical skills. I would be truly delighted to have someone do this analysis.

Since I think the corresponding National Lines of Credit are even more important for Europe than Federal Lines of Credit are for the United States, if you want to do something empirical, to me the key issue is measuring the degree of spillover in fiscal stimulus from one country in the Eurozone to another. Similarly, you could look at the degree of spillover in fiscal stimulus from one U.S. state to another given a state-level fiscal stimulus. However, in general, the amount of empirical precision available for empirical studies of fiscal policy is not great, so this may not be that promising in the end. In either case, DSGE modeling of fiscal spillovers from one Eurozone country to another or from one state to another could be useful.

For other readers, let me translate my statement “the amount of empirical precision available for empirical studies of fiscal policy is not great”:

Despite many claims, aside from military spending, there is not much evidence about the overall effects of short-run fiscal policy on the economy one way or another.

I would be glad to have this claim contested, but I can say that I have seen a lot of economics seminars lately with empirical estimates of the effects of short-run fiscal policy that are all over the map. Valerie Ramey (who has done work on fiscal policy with my colleague Matthew Shapiro) is one of the experts on what evidence exists. Here again is what she had to say about a recent short-run fiscal policy paper by Brad Delong and Larry Summers:

Valerie’s Powerpoint file and Valerie’s writeup of her discussion. There is an active thread on Twitter from my tweeting the link to Valerie’s writeup and calling it devastating.

Now I am not so sure. There are many objections being voiced to Valerie’s discussion. Anyway, the twitter thread backs up the idea that it is hard to get definitive empirical evidence in this area.

By the way, Mark, please leave a comment below giving some indication of your likelihood of pursuing this. If you definitely aren’t pursuing it, letting us know will reassure others that there isn’t too much competition on this research topic.

This post will serve as the Table of Contents for the first month of supplysideliberal.com. But it is more than that. It is a chance to reflect on questions such as

Where have I been coming from in the posts so far?

Why am I here writing a blog?

Where am I going from here?

Only the most important reflections come before the Table of Contents proper. Lesser musings come after the Table of Contents.

The most important thing to say about where I have been coming from is that all the posts are meant to last. I try to make each major post and most minor posts count as parts of overarching arguments that extend over many posts. And I hope that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts, so that anyone who reads the entire thread of posts in a given topic area will learn something they wouldn’t have learned from reading each post in isolation.

I think of blogging as an art form that I am undertaking seriously as a beginning novice. My lodestone for literary structure here is my favorite television series Babylon 5. In Babylon 5, the first season seems episodic, but in fact each episode lays part of the foundation for the narrative arc that picks up in earnest with the second season. Some of the charm of a blog is in its unexpected turns as a blogger interacts with others online. I want to have that and an overall progression.

As to my motivations for beginning a blog, there are many personal motivations that I will talk about in due course. But I know that the one thing that has given me some sense of urgency to start now rather than wait until later is seeing the world economy flounder in the wake of the Great Recession. It is galling to see the world suffering below the world’s natural level of output when, in my contrarian view, getting sufficient aggregate demand is fundamentally an easy problem compared to the long-run challenge of balancing concerns about tax distortions against the value of redistribution and other government spending.

On where I am going from here in this blog, let me say that I have the titles of many potential posts kicking around in my head, each potential post struggling for primacy so it can be the next one written. They can’t all win at any given moment, and I don’t think I can maintain the pace I have kept so far, let alone increase that pace. And responding to other things currently going on in the blogosophere and in the news takes a certain degree of precedence. But there is a lot coming.

The Table of Contents below is organized by topic area. Monetary Policy comes first because responding to other bloggers and to events has led to the most posts in that area. Monetary policy is one way I believe we have plenty of tools to get sufficient aggregate demand. The other way to get sufficient aggregate demand is through Short-Run Fiscal Policy. But in everything I say about short-run fiscal policy, I worry a lot about the effects on the national debt and work to find novel ways to minimize those effects. The third topic area heading is Long-Run Fiscal Policy–the issues that motivate the title of my blog.

The last substantive heading is Long Run Economic Growth. I am not a growth theorist or a growth empiricist, and so am not qualified to say as much as I would like to be able to say about Long Run Economic Growth. But Long Run Economic Growth is arguably the most important subject in all of Economics. I have often thought that if I had started graduate school just a few years later, I would have focused on studying economic growth in my career, as my fellow Greg Mankiw advisee David Weil has to such good effect.

Under the last two headings in the Table of Contents, I organize posts on Blog Mechanics and Columnists, Guest Posts and Miscellaneous Reviews. (I put many reviews under the relevant substantive heading because they help to understand the thread of the argument.) I will talk more about these aspects of the blog and about blog statistics after the Table of Contents.

TABLE OF CONTENTS: FIRST MONTH

Monetary Policy

Balance Sheet Monetary Policy: A Primer

Stephen Williamson: “Quantitative Easing: The Conventional View”

Trillions and Trillions: Getting Used to Balance Sheet Monetary Policy

Karl Smith of Forbes: “Miles Kimball on QE”

Scott Sumner: “‘What Should the Fed Do?’ is the Wrong Question”

Is Monetary Policy Thinking in Thrall to Wallace Neutrality?

Mike Konczal: What Constrains the Federal Reserve? An Interview with Joseph Gagnon

Going Negative: The Virtual Fed Funds Rate Target

The supplysideliberal Review of the FOMC Monetary Policy Statement: June 20th, 2012

Justin Wolfers on the 6/20/2012 FOMC Statement

Should the Fed Promise to Do the Wrong Thing in the Future to Have the Right Effect Now?

Wallace Neutrality and Ricardian Neutrality

Short-Run Fiscal Policy

Getting the Biggest Bang for the Buck in Fiscal Policy

Reihan Salam: “Miles Kimball of Federal Lines of Credit”

Long-Run Fiscal Policy

What is a Supply-Side Liberal?

Clive Crook: Supply-Side Liberals

A Supply-Side Liberal Joins the Pigou Club

“Henry George and the Carbon Tax”: A Quick Response to Noah Smith

Long-Run Economic Growth

Leveling Up: Making the Transition from Poor Country to Rich Country

Blog Mechanics

Columnists, Guest Posts, and Miscellaneous Reviews

An Early-Bird Tweet from Justin Wolfers

Noah Smith: “Miles Kimball, the Supply-Side Liberal”

Diana Kimball on the Beginnings of supplysideliberal.com

Gary Cornell on Intergenerational Mobility

supplysideliberal.com Takes on a Math Columnist: Gary Cornell on the Financial Crisis

Let me say a few words about blog mechanics, columnists, reviews and blog statistics. The most important blog mechanics are indicated by links at the sidebar. But the posts under Blog Mechanics provide a little more detail. On all the blog mechanics, I owe a great debt to my daughter Diana Kimball.

I have already said it in several posts, but let me say again that those who are not following my tweets are missing a lot. I have been having a lot of fun engaging with the news of the day and with other people’s tweets. And I routinely tweet announcements of new posts appearing on the blog itself.

Among the Miscellaneous Reviews, the one I recommend most highly is Noah Smith’s. I owe a lot to Noah’s encouragement and help with this blog. I see this blog as part of the Noahpinion universe.

On blog statistics, I will do a separate post a little later on traffic sources, which is interesting because it helps show the shape of my corner of the blogosphere. My first post was on Memorial Day, May 28, 2012, exactly one month ago. I didn’t get Google Analytics set up until a few days later, so those statistics are from Sunday, June 3 on (and end at midnight last night). Google Analytics reports 20,386 total pageviews, 13,392 visits, and 7,411 unique visitors. I got some help “grep"ing to verify that the Google Analytics statistics do not include the now 593 subscribers receiving the posts on Google Reader unless they also click separately from Google Reader. Together with the 62 Tumblr subscribers, that adds up to 655 subscribers, plus some number of subscribers on Facebook that I can’t separate out from other Friends and however many subscribers I have on other platforms I don’t know about. Finally, I have 353 Twitter followers. The mismatch between that and the number of subscribers to the blog itself is why I have been making a point of recommending following my tweets.

To me, this past month has been a heady time. The excitement of starting a new blog that has been so generously welcomed has caused me some of the most pleasant insomnia that I have ever experienced. One of the reasons I expect to slow my pace somewhat is that once that enthusiastic insomnia wears off, I will have less time to blog.

Update: I added posts from the rest of June, 2012 to the Table of Contents above so that from now on monthly tables of contents can be based squarely on calendar months.

It is always interesting to read reviews. Google Analytics helped me find Mike Sax’s very interesting review as a significant source of referrals. I thought I would share this with you. Let me give a disclaimer: the opinions about other blogs are Mike’s, not mine. Consider my level of endorsement the same as if I had approved it as a comment. Also, the title of Mike’s blog, “Diary of a Republican Hater” does not apply to me. I like Republicans very much and I like Democrats very much. I hope that each side feels I agree with them on those views that they think can most clearly be defended by rational argument. Thanks to Mike for permission to reprint this review:

NGDPLT, ‘Wallace Neutrality" and Related Matters

I can now stand out of a limb and say that the start of Miles Kimbal’s Supply Side Liberal blog is a very positive development for all of us who want a better and deeper understanding of all matters Econ. Since the crisis one positive has been a veritable flowering of Econ blogs along the lines of what the French Salons were back in the 18th century for intellectual discourse on the news of the day.

Many as I do read Sumner’s Money Illusion and other MMers like Nick Rowe, Lars Christensen, et al as well of course as the “Saltwater” guys like Krugman and Delong. Then of course you have the MMTers-today’s Post Keynesians-at places like Economic Perspectives and the Center of the Universe-Walter Mosler’s blog. Another good one is Cullen Roch who is even within MMT heretical breaking up into yet another school-MMR. There are many others I’m not mentioning that are tremendous-Noahpinion, Bill Woolsely…

Through all of it what I’ve personally sought certainly is for true teachable moments-I want to learn and understand the marcro and monetary system better. Of course whether you are reading an MM blog, an MMT or a New Keynesian blog of course the author usually has a strongly advocated point of view. This is not a problem as far as I’m concerned-I too have a point of view. I’m basically I’d say a Post Keynesian though I’m not sure I’m ready to embrace the MMT tag-it seems somewhat cultish too me.

I think it can’t be denied that if any one person comes closet to epitiomizing the flowering of Econ since 2009 it may be Sumner himself. Certainly no one doubts his point of view but I don’t see how you can deny he’s been a “tree shaker.” I use that phrase thinking of what Jesse Jackson used to say-“I’m a tree shaker not a jelly maker!”

This doesn’t mean Sumner’s right. I think it’s still very open to question whether he’s right about NGDP level targeting working exactly the way he assures us it will. But no doubt he has captured the imagination of many Econ bloggers no doubt.

What NGDPT has going for it is for one thing the “vaccuum effect.” No other theory in the Macro world right now is so suggestive, intuitive, and has such reach in terms of explanatory power. It does remind in me in some way of Chomsky’s linguistic revolution in the 60s. Whether he was right or not, Chomksy couldn’t be beaten because no one else could suggest a system that seemed to explain so much. Here I can’t but think of Kuhn's Structure of Scientific Recvolutions.

In this way Sumner is very much like his hero-he is Friedman 2.0 in the sense that his NGDPLT idea is probably the most intuitive and trendy single monetary idea since Friedman’s 3% money supply growth rule.

Still as Noah Smith has suggested, intuitiveness is not in itself proof of truth. Friedman’s Rule was also highly intuitive and yet it was a disaster. That doesn’t mean I can tell you right now what might be the hole in NGDPLT. I’m not certain there is one that it will go as badly askew as Friedman’s Rule just that it could.