Negative rates make all the old issues in monetary policy new. Monetary economists didn’t have a consensus on the transmission mechanism for interest rate cuts when rates were in the positive region, but almost no one doubted that rate cuts were, indeed, stimulative in the positive region because there was so much experience showing that they are. Predicting what will happen in the negative region makes monetary theory important. This post lays out the relevant theory. If you disagree, please identify the particular part of the logic of the theory below that you disagree with; I’d love to have you put your critique in a comment.

The first thing to say theoretically is that the effects of interest rate cuts are likely to be continuous. Hence, a very small interest rate cut, such as the 10 basis points that the Bank of Japan went negative, would be unlikely to have a big effect.

Beyond that point, I need to set the stage. I am interested in the effects of rate cuts that are combined with other policies so that they (a) don’t hurt bank balance sheets and (b) don’t cause any massive increase in paper currency storage.

On (a), in the real world, most central banks that use negative rates use tiering of the interest-on-reserves formula or below-market-rate lending to private banks to protect the balance sheets of private banks from negative effects from negative rates. This is certainly what I recommend. (See “Responding to Negative Coverage of Negative Rates in the Financial Times” and Ruchir Agarwal’s and my paper: “Enabling Deep Negative Rates to Fight Recessions: A Guide.”)

As they acknowledge, Markus Brunnermeier and Yann Koby's "Reversal Interest Rate" comes from a model that assumes, contrary to what happens in the real world, that the central bank will do nothing to bolster bank balance sheets when rates are cut in the negative region. Central banks are smarter than that.

On (b), a large share of what I have written or coauthored about negative rate policy has been about modifying paper currency policy in a way that avoids massive paper currency storage. On that, let me refer you to my bibliographic post “How and Why to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound: A Reader’s Guide,” and especially the papers I highlight at the top there.

To put a point on things, I totally concede that the monetary transmission mechanism might be different in the negative region if a central bank does not protect bank balance sheets or does not modify paper currency policy. This is not relevant to my proposals the more detailed proposals that Ruchir Agarwal and I have made in our papers on negative interest rate policy. But I know that what might happen if a central bank does not protect bank balance sheets or does not modify paper currency policy affects many people’s intuitions about negative interest rate policy, even where those situations are not relevant. Please try to take seriously the assumption that the bank profits problem and the paper currency problem have been neutralized as I go on to discuss the transmission mechanism for rate cuts when those issues have been taken care of.

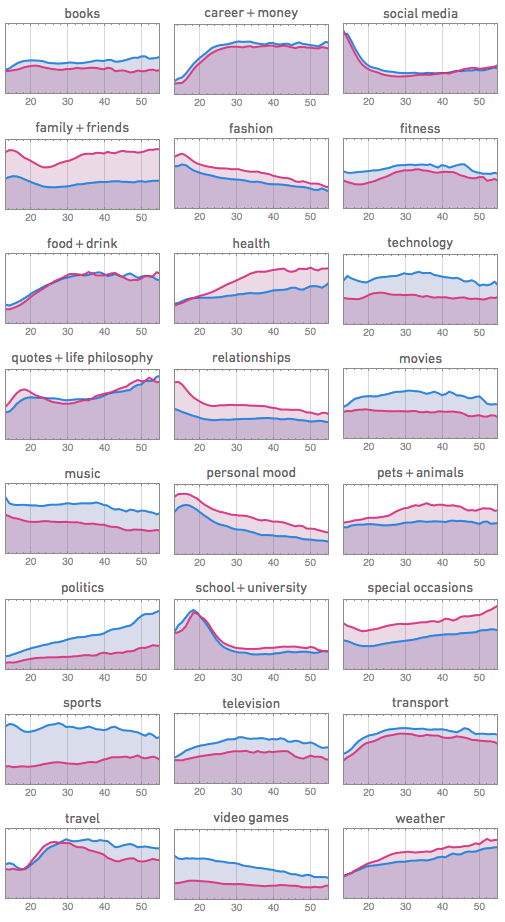

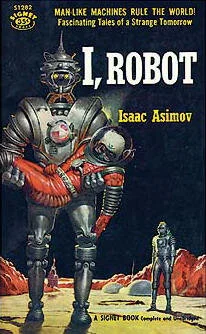

The diagram at the top of this post gives my perspective on the transmission mechanism for rate cuts. All of the logic in that diagram holds up 100% even when rates are negative.

Like many monetary economists, I think that the transmission mechanism for monetary policy works almost entirely through the interest rate movements it engenders. There are two subtleties:

There are many interest rates, and which assets a central banks buys (say in QE) can affect different parts of the risk- and term-structure of interest rates differently.

Expectations about the entire future path of interest rates matters. This is the lever through which forward guidance can work.

I won’t deal with these two complications in this post. But in the diagram at the top of the post, I do indicate the perspective I teach my students about how most central banks move: short-term risk-free interest rates: Supply and Demand for the Monetary Base.

Once interest rates go down, there are three categories of effects: open-economy effects, wealth effects that would happen even in a closed economy, and the direct substitution effect from the interest-rate cut. Most economists will find what the diagram says about open-economy effects and the direct substitution effect routine, though it takes some care to work through all of the open-economy effects.

I only learned what is in the diagram about the direct wealth effects from rate cuts from thinking about negative rate policy. I named the key insight The Principle of Countervailing Wealth Effects. I wrote about this principle first in my rejoinder to Mark Carney, “Even Central Bankers Need Lessons on the Transmission Mechanism for Negative Interest Rates.” Two other posts followed that up: “Responding to Joseph Stiglitz on Negative Interest Rates” and “Negative Rates and the Fiscal Theory of the Price Level.”

Importantly, The Principle of Countervailing Wealth Effects—particularly the principle that the change in the present value of what the debtor owes is equal and opposite to the change in the present value of what the lender is owed—operates just as well in a fully dynamic model as in a simplified model. If there is no borrowing and lending in the initial situation, there will be no wealth effects from a small interest rate change. Note that in a dynamic model, one is in danger of misanalyzing the effects of interest rate changes if one does not recognize the change in the present value of the consumption path planned in the initial situation as well as the change in the present value of the income stream.

In a dynamic model, no borrowing and lending doesn’t have to come from everyone being identical: those of one type could be very impatient (high utility discount rate), but have income front-loaded enough that they don’t need to borrow, while those of the other type is very patient (low utility discount rate), but have income back-loaded enough that they don’t need to lend. And if the two types have different elasticities of intertemporal substitution, borrowing and lending will arise as rate changes move things away from the initial situation. (In a simple model, the rate changes might need to come from a change in a storage technology; in more complex models the rate changes can come from central bank actions.)

The key question is unaffected by how dynamic and how complex the model of borrowing and lending is:

Which is bigger, the marginal propensity to spend (domestically on C, I and G) of the borrower compared to the marginal propensity to spend of the lender?

If the marginal propensity to spend of the borrower is greater, than the net wealth effect of a rate cut when aggregating over the borrower and lender in any borrower-lender relationship is stimulative. If the marginal propensity to spend of the lender is greater, then the net wealth effect of a rate cut on the combined spending of that particular borrower-lender pair is contractionary, but other borrower-lender pairs, the substitution effect and open-economy effects could still make the rate cut stimulative overall. Thus:

It is a good exercise to try to identify borrower-lender pairs for whom the marginal propensity to spend is higher for the lender than for the borrower. This will be hard. If you think you have succeeded, definitely tell me what you found in a comment!

However, a particular type of borrower-lender pair that does have the lender’s marginal propensity to spend higher has to be numerous enough and important enough to outweigh the net wealth effects from all the other types of borrower-lender pairs, as well as the substitution effect and open-economy effects if they are on net stimulative (as they will be if the straightforward exchange-rate effect on net exports dominates).

It is a tall order to meet this standard for rate cuts to be contractionary. The most likely case for rate cuts to be contractionary is if a nation has a massive amount of foreign-currency-denominated debt. That is, I think the open-economy effects having to do with foreign debt are the one plausible reason for interest-rate cuts to be contractionary. (Of course, if interest rate cuts are contractionary locally, then interest-rate increases will be stimulative locally, so monetary policy can still stimulate.)

Except in one situation, I think it is very, very hard to maintain that in the real world borrowers overall have lower marginal marginal propensities to spend than lenders, weighting by magnitude of borrowing. As long as borrowers have a higher marginal propensity to spend than lenders, the bottom line is this: the direct wealth and substitution effects of interest rate cuts are unambiguously stimulative, so rate cuts will be unambiguosly stimulative overall if net open-economy effects from rate cuts are stimulative.

What is the one exception I can see? It is actually about rate increases being stimulative, not directly about rate cuts being contractionary. In many hyperinflationary situations, the government feels unable to cut back spending any more, so that its marginal propensity to spend less when its interest rate expenses increase is close to zero—less than the marginal propensity to spend of the bondholders out of their extra interest-rate income. Other than that, it is hard to think of a weighty exception to the the norm that borrowers have a higher marginal propensity to spend than lenders.

This bottom line based on the forces we have analyzed so far leaves two questions:

Q: What will happen to the magnitude of the effects in the diagram when rates start deep in negative territory?

A: It is hard to see why the gap between marginal propensities to spend of borrowers and lenders should narrow dramatically as interest rates go lower. And notice that there is no serious problem for monetary policy firepower if the gap narrows somewhat. As long as the sign of the gap continues to make the marginal propensity to spend higher for borrowers than lenders, there is still the direct substitution effect and the open-economy effects. And their is no plausible real-world reason for the substitution effect to become dramatically smaller as rates go lower. Indeed, negative rates are especially salient, and deep negative rates even more salient, so if one adds in some behavioral-economics effects, one would expect the substitution effect to get somewhat bigger as rates go lower. (Why would deep negative rates be even more salient than shallow negative rates? At some point, rates are negative enough that even after a risk premium is added on top of the risk-free rate, more and more borrowers can borrow at a negative rate at least for short maturities. That is salient!)

Q: What important effects are omitted that need discussion? The main additional effects I can think of are nominal-illusion effects. The key thing here is that nominal-illusion effects will affect borrowers or lenders. So it is important to think about the net effect aggregated over borrowers and lenders of nominal illusions interacting with rate cuts. To me, it seems most plausible that nominal-illusion effects are like the salience effects I discussed above: juicing up the effects of interest-rate cuts on both borrowers and lenders. And borrowers tend to be either equally or less sophisticated than lenders. So the effects of interest rate cuts should be juiced up by nominal illusions more for borrowers overall than for lenders.

Conclusion: Let me conclude by pointing out that it is very easy to make theoretical models in which the marginal propensity to spend is higher for lenders than for borrowers. It is just that those parameter values aren’t very plausible in the real world. A simple example is that in a two-period model one could have for lenders highly curved period-utility in the second period but very slightly curved period-utility in the first period (more or less a “target retirement consumption” utility function) and do the opposite for borrowers: highly curved period-utility in the first period but very slightly curved period-utility in the second period. But why assume such different functional forms for borrowers and lenders? Isn’t it more likely that they have similar functional forms but different utility discount rates (levels of impatience)?

When it comes down to it, do we really believe empirically, in the real world, that there are weighty parts of the economy where lenders have a higher marginal propensity to spend than borrowers? I think not. And if I am right about the rarity of marginal propensities to spend that are higher for lenders in a borrower-lender pair, then only open-economy effects can overturn the idea that rate cuts remain substantially stimulative however low rates go. (“Substantially stimulative” means that there is a strictly positive lower bound on how stimulative a 100-basis-point cut will be, no matter how low rates have gone already.) That yields unlimited monetary-policy firepower if one has addressed the bank profits problem and the paper currency problem so that rates can go as low as necessary.