Building Up With Grace

High rises don't have to be soulless. In "Density is Destiny" I wrote about the importance of density for economic growth. The way to have density and still have space for people in their homes is to build up. I also tried my hand in "Density is Destiny" at sketching a possible design for pleasant high-rises that I think can ultimately be built at non-luxury prices. Anna Baddeley's article linked above talks about some innovative architectural designs for high rises that I suspect might be at the higher end, but might become more affordable with technological progress.

Urban density contributes to creativity and therefore to economic growth. Moreover, greater density through relaxing height restrictions is important for helping those with lower incomes and therefore for social justice. Experience has shown that it is very difficult to move good jobs to people. But it is easy for people to move to where good jobs are if affordable housing is available. The phrase "affordable housing" has often been used for a token amount of subsidized housing. But the principles of supply and demand mean that the only way to have affordable housing for the masses is to allow construction of many more units.

High density does not mean that height restrictions need to be removed everywhere within an urban area. That can be some low-density subdivisions for the rich folks. But in my view social justice requires that every metropolitan area has some large section with essentially no height restrictions for residential buildings (other than those genuinely required by earthquake concerns) and very frequent and convenient bus service from the high section of the city to jobs in the rest of the city.

It is far from certain that we will realize the social justice requirement of a high section to every city. But I want to encourage social-justice-minded architects to prepare for that hoped-for day by thinking about graceful and pleasant designs that can give good homes to people at a wide range of different income levels. Showing in principle how good high rises can be even for those of modest means could do a lot to make it politically feasible to shift policies toward letting more people into our most vibrant cities.

John Locke: Theft as the Little Murder

In section 11 of his 2d Treatise on Government: On Civil Government," John Locke sets down a very different moral basis and very different location of the right of enforcement for civil as opposed to criminal law:

From these two distinct rights, the one of punishing the crime for restraint, and preventing the like offence, which right of punishing is in every body; the other of taking reparation, which belongs only to the injured party, comes it to pass that the magistrate, who by being magistrate hath the common right of punishing put into his hands, can often, where the public good demands not the execution of the law, remit the punishment of criminal offences by his own authority, but yet cannot remit the satisfaction due to any private man for the damage he has received. That, he who has suffered the damage has a right to demand in his own name, and he alone can remit: the damnified person has this power of appropriating to himself the goods or service of the offender, by right of self-preservation, as every man has a power to punish the crime, to prevent its being committed again, by the right he has of preserving all mankind, and doing all reasonable things he can in order to that end: and thus it is, that every man, in the state of nature, has a power to kill a murderer, both to deter others from doing the like injury, which no reparation can compensate, by the example of the punishment that attends it from every body, and also to secure men from the attempts of a criminal, who having renounced reason, the common rule and measure God hath given to mankind, hath, by the unjust violence and slaughter he hath committed upon one, declared war against all mankind, and therefore may be destroyed as a lion or a tyger, one of those wild savage beasts, with whom men can have no society nor security: and upon this is grounded that great law of nature, “Whoso sheddeth man’s blood, by man shall his blood be shed.” And Cain was so fully convinced, that every one had a right to destroy such a criminal, that after the murder of his brother, he cries out, Every one that findeth me, shall slay me; so plain was it writ in the hearts of all mankind.

That is, in the state of nature, everyone has the right to enforce natural criminal law, but the right to enforce natural civil law (or have an agent enforce it) belongs to the one wronged.

In his discussion of natural criminal law, I am struck by John Locke's repeated recourse to murder as a metaphor for other crimes as well. In section 6, he makes the connection explicit:

[One] may not, unless it be to do justice on an offender, take away, or impair the life, or what tends to the preservation of the life, the liberty, health, limb, or goods of another.

A possible reaction to this might be that in 1689, when John Locke published the Two Treatises of Government, even many people in upper percentiles of the population in income were living close enough to the margin that the typical effect of having goods stolen on mortality was much greater than it would be for the rich today. But that is much too partial an analysis. If theft is not deterred in a nation, the whole nation will remain poor and many, many will die. Blocking theft, deception and threats of violence are the most basic tasks of government in order to give a nation a fighting chance to become rich. (See my column "The Government and the Mob" for a related discussion.) Most of the poorest nations on earth are poor either because of some failure to block theft, deception and threats of violence on the part of private individuals or because the government itself has resorted too readily to theft, deception and threats of violence.

Nevertheless, when carefully regulated so as not to interfere with economic growth, "theft" by the government of resources from the very wealthy probably cannot be appropriately called a "little murder." But other things equal, actions that do inhibit economic growth will have a cost in lives, and are hard to justify unless they contribute to the preservation of life enough in other ways to counterbalance the lost life from slower economic growth.

The Evolution of the Dominant Sector of the Economy of Each US State, 1990-2013

Images and data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, gif from Reddit user mobuco, via Reid Wilson's September 3, 2014 Washington Post article "Watch the U.S. transition from a manufacturing economy to a service economy, in one gif."

The Supply and Demand for Paper Currency When Interest Rates Are Negative

Note: The acronym "ROERC" is pronounced in the same way as Howard Roark's last name. It stands for "Rate of Effective Return on/for/of Cash.

Why the Rate of Effective Return on Cash Curve Slopes Down

Ruchir Agarwal and I argue in our IMF working paper "Breaking Through the Zero Lower Bound" that when deep negative interest rates are needed for prompt macroeconomic stabilization, central banks should take paper currency off par. (On this point, also see "How and Why to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound: A Reader's Guide.") But what if a central bank is legally or politically unable—or unwilling—to take paper currency off par? In our nascent paper "Implementing Deep Negative Rates"—and the Powerpoint presentation of the same name—Ruchir and I argue that a variety of measures can be taken to make an arbitrage using massive paper currency storage more difficult. We call this "the dirty approach" to dealing with the paper currency problem. Moreover, we argue that political economy forces are favorable for many of the measures in the dirty approach, whether taken by a central bank or by other arms of its government. First, versions of many of these measures are already being taken. Second, how many governments would really stand by and do nothing while private agents piled up in storage a substantial fraction of GDP in paper currency? That is, for the US, is it plausible that the government would stand by and do nothing as private agents pile up trillions and trillions of dollars worth of paper currency?

Six measures in the dirty approach to the paper currency problem (which you can see discussed on video in "Enabling Deeper Negative Rates by Managing the Side Effects of a Zero Paper Currency Interest Rate: The Video") are

- Ban Electrification of Paper Currency. That is, prohibit any money market mutual funds or similar securities that have on their asset side more than a small percentage of paper currency. Though only a partial implementation of this measure, it is an open secret I heard from multiple sources in various places around Europe and elsewhere in the world that the Swiss National Bank has been using moral suasion to discourage financial firms from offering easily traded assets backed by paper currency.

- Use the Interest on Reserves Formula to Subsidize Zero Rates for Small Household Accounts. This would reduce the motivation for households to withdraw money from the bank and store it as paper currency, helping to avoid a "death of a thousand cuts" of small-scale paper currency storage by many households that could add up to a large total quantity of storage. See "How to Handle Worries about the Effect of Negative Interest Rates on Bank Profits with Two-Tiered Interest on Reserves Policies," "Ben Bernanke: Negative Interest Rates are Better than a Higher Inflation Target," and "The Bank of Japan Renews Its Commitment to Do Whatever it Takes." No central bank has done this yet, but the reception I have had for this proposal is quite favorable. And several central banks already have quite complex tiered interest-on-reserves formulas.

- Charge Banks for Excess Paper Currency Withdrawals from the Cash Window, Allowing Them to Impose Restrictions in Turn. The Swiss National Bank and the Bank of Japan already have provisions in their tiered interest-on-reserves formulas that penalize banks for cumulative withdrawals of paper currency. This is a way of directly having negative interest rates on paper currency in the relationship between the central bank and private banks. However pass-through of paper currency to households may not currently be counted as part of those cumulative withdrawals. If it were, that would inhibit banks from giving out paper currency so freely.

- Retire Large Denomination Notes of Paper Currency. This is under serious discussion in many countries. In action, the ECB has decided to eliminate the 500-euro note.

- Ban Storage of Paper Currency as a Business. Note that, given the substantial economies of scale and what would be sunk costs in setting up a paper currency storage business, even the threat of future action banning this business can do a lot to stunt its growth.

- Put Tight Restrictions on Flows of Paper Currency Out of the Country. This is a small step from restrictions and hindrances to flows of paper currencies in and out of a country that are in place for other reasons.

I argue that these kinds of measures (and perhaps inherent obstacles in place even without these kinds of measures) make the marginal rate of effective return on paper currency decreasing in the currency-region-wide amount of paper currency being stored, as shown in the graph of the rate of effective return on cash (ROERC) curve at the top of this post. Such difficulties tend to push the rate of effective return on cash below its superficial return of zero. If any dirty hindrances to redemption of paper currency into reserves (electronic money) are added, that would add to the downward slope of the ROERC curve on the right.

On the left of the curve, the rate of effective return on cash is far above its superficial return of zero for the amount of paper currency needed to carry on high-demand illegal activities—including, notably, tax evasion. (The secrets people want most desperately to keep are typically secrets from the government, but there is some demand for cash in order to keep secrets from others.)

The Opportunity Cost of Cash Curve

The ROERC curve is the demand curve for paper currency. The supply curve for paper currency is the Opportunity Cost of Cash (OCC) curve.

To the private sector, the maximum possible potential supply quantity of paper currency is the entire monetary base. Without reducing the amount of loans, the potential supply of paper currency is the monetary base minus required reserves. But even beyond required reserves, there may be some amount of excess reserves that has value as a buffer stock and so has an implicit return beyond the interest on reserves (shown as a negative rate above, as in several countries now). If the monetary base is large, as it is now, the marginal opportunity cost for quite a bit of paper currency would be very close to the interest on reserves (IOR). But beyond some level, additional paper currency would require reducing excess reserves that have some significant value as a buffer stock, so above that level of paper currency, the opportunity cost of cash would rise above IOR.

In drawing the opportunity cost of cash curve, I am heavily influenced by having seen Ricardo Reis's Jackson Hole Presentation "Funding Quantitative Easing to Target Inflation." Ricardo argues that in the US, the value of reserves—and therefore the opportunity cost of cash—only drops to IOR after excess reserves reach about $1 trillion.

Putting the ROERC and OCC Curves Together

The Classic Zero Lower Bound Argument

The classic zero lower bound argument corresponds to a ROERC curve flat at zero once certain high-priority demands for paper currency have been satisfied:

With a ROERC curve flat at zero beyond a certain point, the interest rate won't drop below zero even if the monetary base is large and IOR is negative. Moreover, starting from that situation, increasing the monetary base will do nothing to the interest rate, which will stay at zero.

Similarly, starting from that situation, reducing IOR even further will do nothing to the interest rate:

An Effective Lower Bound Below IOR

Now, what if there is a constant storage cost of paper currency. This make the ROERC curve flat at a level below zero after a certain point. This flat ROERC curve creates an effective lower bound below zero. If the IOR is still above that effective lower bound, a cut in IOR will lower the interest rate:

As long as the effect rate of return on cash is below IOR, it is IOR, not the effective return on cash that is crucial for determining the interest rate. Indeed, assuming the monetary base is large enough that the function of marginal reserve is simply to earn IOR on them, increasing the monetary base further has no effect on the interest rate, it just increases excess reserves.

Again, because the effect return on cash is below IOR, paper currency isn't affecting things very much.

An Effective Lower Bound Above IOR

By contrast, if the effective rate of return on cash is above IOR, constant beyond a certain amount of paper currency that has already been exceeded, then both reductions in IOR and open market operations do nothing to the interest rate:

The Clean Approach: Cutting the Effective Rate of Return on Paper Currency Using a Depreciation Mechanism

Sticking for simplicity with a flat ROERC curve beyond a certain point, one can illustrate the effect of having the exchange rate for paper currency in terms of reserves gradually decline over time with a downward shift in the ROERC curve. Here the idea is to cut the paper currency interest rate (PCIR) in tandem with cutting IOR:

The PCIR or effective rate of return on cash is cut by making the exchange rate at which paper currency can be exchanged for reserves at the cash window drift downward more strongly. Obviously, doing this requires being willing to contemplate an exchange rate between paper currency and reserves that can become different from par. Being willing to take paper currency off par opens the possibility of making the effective return on paper currency a policy variable. The bulk of the links in "How and Why to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound: A Reader's Guide" point to discussions of this approach. (On the cash window itself, see "An Underappreciated Power of a Central Bank: Determining the Relative Prices between the Various Forms of Money Under Its Jurisdiction.")

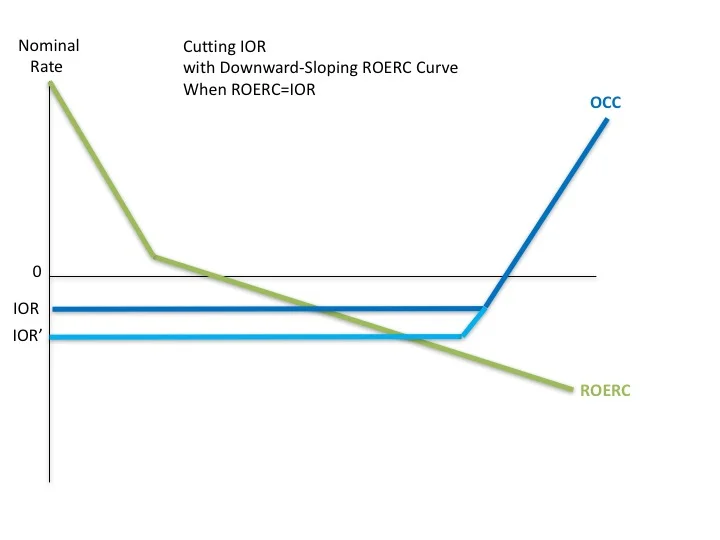

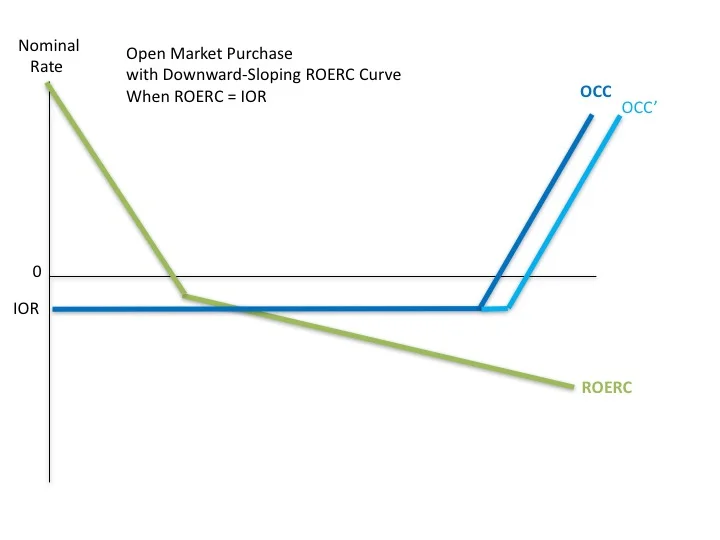

A Downward Sloping ROERC

If the ROERC curve is downward sloping, for whatever reason—and the monetary base is large enough to make the opportunity cost of cash equal to IOR—reductions in IOR lower the interest rate even if the exchange rate at the central bank's cash window between paper currency and reserves is left at par:

With the monetary base already large enough to make the opportunity cost of cash equal to IOR, open market purchases without any reduction in IOR do not affect the interest rate:

On the other hand, if the monetary base isn't large enough to make the opportunity cost of cash equal to IOR, reductions in IOR don't lower the interest rate, but open market purchases do:

The Lump-of-Labor Model

"In France, as in other parts of Western Europe, the reigning explanation for unemployment was what economists call the “lump of labor” theory. The theory holds that a society has only a fixed amount of work that needs to be done, and therefore the only way to reduce unemployment is to share the available work. This was reflected in Mitterrand’s initial program. The government lowered the retirement age to sixty to push older people out of the workforce; this was expected to create openings for youngsters, on the assumption that each employer needed only a certain amount of labor and would replace departing workers one for one. Workers who reached age fifty-five could collect pensions equal to 80 percent of their wages if their employers agreed to replace each retiree with a worker under twenty-five. The regular workweek was cut from forty hours to thirty-nine, and the maximum workweek was reduced as well, in the expectation that employers might cover those hours by adding workers. The possibility that less work for the same pay might deter hiring, or that young workers might lack the skills of the experienced workers they were replacing and therefore have lower productivity, was not widely discussed in the France of 1981."

--Marc Levinson, An Extraordinary Time: The End of the Postwar Boom and the Return of the Ordinary Economy

Paula Kimball Gardner, Mary Kimball Dollahite and Sarah Camilla Kimball Whisenant on Edward Lawrence Kimball

Edward Lawrence Kimball

Paula:

My father was the most kind and gentle man I know. He filled many roles during his life but most importantly he is my dad.

I remember spending a day with him in his office at work. I remember meeting him at the bus stop as he came home from work. I remember helping him by turning the pages for the hundreds of law exams he read. He helped me make a wooden frame for a stitchery I did once. He gave me many fathers blessings over the years.

In a family role he helped wash dishes after meals. As a family we went on trips in the summer. In Wisconsin our yard was shaded with lots of trees so he was our cheerleader as we raked the leaves in the Fall. He was sure we knew about our ancestors through books, stories and reunions. Daddy would walk on his hands and loved to recite the Jabberwocky adding his own actions.

He loved music. He played for enjoyment and as we sang. Each of us practiced piano and in a loud voice from a different room he would say 'wrong note'. He accompanied me as I played my bassoon solos. He taught us family songs that we still sing and enjoy today. He taught us Dutch St. Nickolas songs he learned on his mission. I learned to love music too. Because we only got one session of General Conference in Wisconsin I tried to find my Aunt Bobby who sang with the Mormon Tabernacle Choir and was proud when did.

He loved the Lord. He served a mission and served in many church callings. He was bishop twice and served in a BYU Stake Presidency. In Wisconsin he helped build the chapel we met in for many years.

My dad was a wonderful man. Some descriptions my kids gave of him are loving, genuine, noble, honorable, kind, wise, strong, temperate, authentic, witty and grateful. You may have you own description of him but he is my dad and I love him.

Mary:

Dad loved music. He was my first piano teacher. He taught me to sing parts during Church. Dad kept a harmonica, a jaw harp, a kazoo, and other small instruments in his desk drawer. He often played one while thinking, or to entertain me.

Dad loved sports. Because of polio, he did not play basketball or football or tennis, but when I sat next to him at my four brothers’ wrestling matches, I watched him get as much of a work out as they did. Dad was a University of Utah fan and a BYU cougar fan.

Dad instilled frugality and taught me how to prepare leftovers. This is his recipe (when Mother was out): 1. Find all the leftovers in the refrigerator and empty them into a saucepan, 2. Add one can cream of mushroom soup, and 3. Heat until warm.

Dad was a top-notch editor. I remember him (at my request) taking just five minutes to mark my rambling three-page high school English essay and turning it into two coherent paragraphs.

Dad honored the priesthood. When I was 21, I asked for a priesthood blessing quite late at night. He said, after a question or two, “I’ll be there in three minutes.” He dressed – complete in a white shirt – and gave me a blessing.

Dad taught me in his learning. He taught me about being fair to the penny and generous to the dollar. He taught me the strength of quiet faith by living quietly faithfully. When I realized that one of the people I most admired was Dad – how I he thought and how considerate he was of other people’s thoughts – I became one of his students at the law school.

Dad built others. I cannot count the times he commented – simply because I was there and just because he could -- what has become a phrase of his I will most miss: “You’re a gem.” He kept a few of his father’s pre-stamped penny postcards in his desk to remind himself how easy it was to send a note of appreciation.

Recently, during a visit, Dad expressed a last wish, saying, “I just want to be remembered as a loving father.”

As with my writing, Dad, you’ve put a concise name to my memory: I remember you as a loving father.

I am grateful to our Heavenly Father for all loving earthly mothers and fathers. In the name of Jesus Christ, amen.

Sarah:

"…Gently they go, the beautiful, the tender, the kind;

Quietly they go, the intelligent, the witty, the brave…"

--from "Dirge Without Music," by Edna St. Vincent Millay

To borrow my Dad’s phrase, “Ed Kimball is gone,” and I will miss the physical presence of his wit, wisdom and warmth. I’ll miss his strong, harmonious singing voice; his humor and wry smile; his tender hand. It has brought me some measure of comfort to think of the aspects of him that I can continue to have with me in all that he has given us through the years.

I once told him that I thought he knew how to do everything, when I was young. He could play, not only the piano, but the harmonica, the accordion, the trumpet, the triangle and more. He could walk on his hands, juggle and could recite from memory several, long poems. He listened to me laud his abilities and then he chuckled. He certainly tinkered with all lot of interests, but said he that didn’t know everything. From him I learned to love trying new things.

My Dad assigned himself the task of weeding. He enjoyed it. One day after I knew he had spent several hours outside working I saw that he had placed in the middle of the kitchen counter, for my mother, a tiny vase with a single, tiny, purple flower. He strove to see the beauty and goodness in all things and all people.

I enjoyed his adventurous and curious spirit. About 3 years ago he and I were driving up Provo Canyon. He suggested we take a detour and explore a small side road. What a joy it was to be along for the ride.

He loved people. He considered himself shy, but yet he knew people. He was fascinated so much that he asked how different individuals were doing and when loved ones came to visit he knew just how to converse with them. I watched in awe and appreciation. About a month before he was gone I brought him a bowl of ice cream. He took a few bites, looked up and said, “Tell someone they’re my friend and give them ice cream.” He often thought of others before himself.

He was generous with his appreciation and expressed his appreciation for my husband and me living there with him. One night he thanked me for being so generous. I explained that they, he and Mother, had always been generous with me. They had taught me all I know and I was just doing the same as they had shown as loving examples and that I owed him. He sleepily responded, “I don’t think so, but let’s pretend,” and smiled wryly. He was so gracious and so kind.

In these past years as I tucked him into bed, I wanted to give him permission to have his hearts desire to be with my mom, his beautiful best friend. I would give him a hug and kiss him on the forehead and say, “Dad, if you are here in the morning I will be delighted, and if you slip away peacefully in the night, know that I love you … and let mom know. "

Oh, how I love you, Dad, for all your wit, wisdom, creativity, your quest for knowledge and truth, your love and thoughtfulness. I still have all that with me and always will.

Abby Ohlheiser on the Peril and Potential of FamilyTreeNow →

My brother Joseph pointed me to this article. The free site FamilyTreeNow can help you find long-lost friends or distant relatives or let a stalker find you. If you don't want to be found, you can apparently opt out.

Border Adjustment vs. Dollar Depreciation

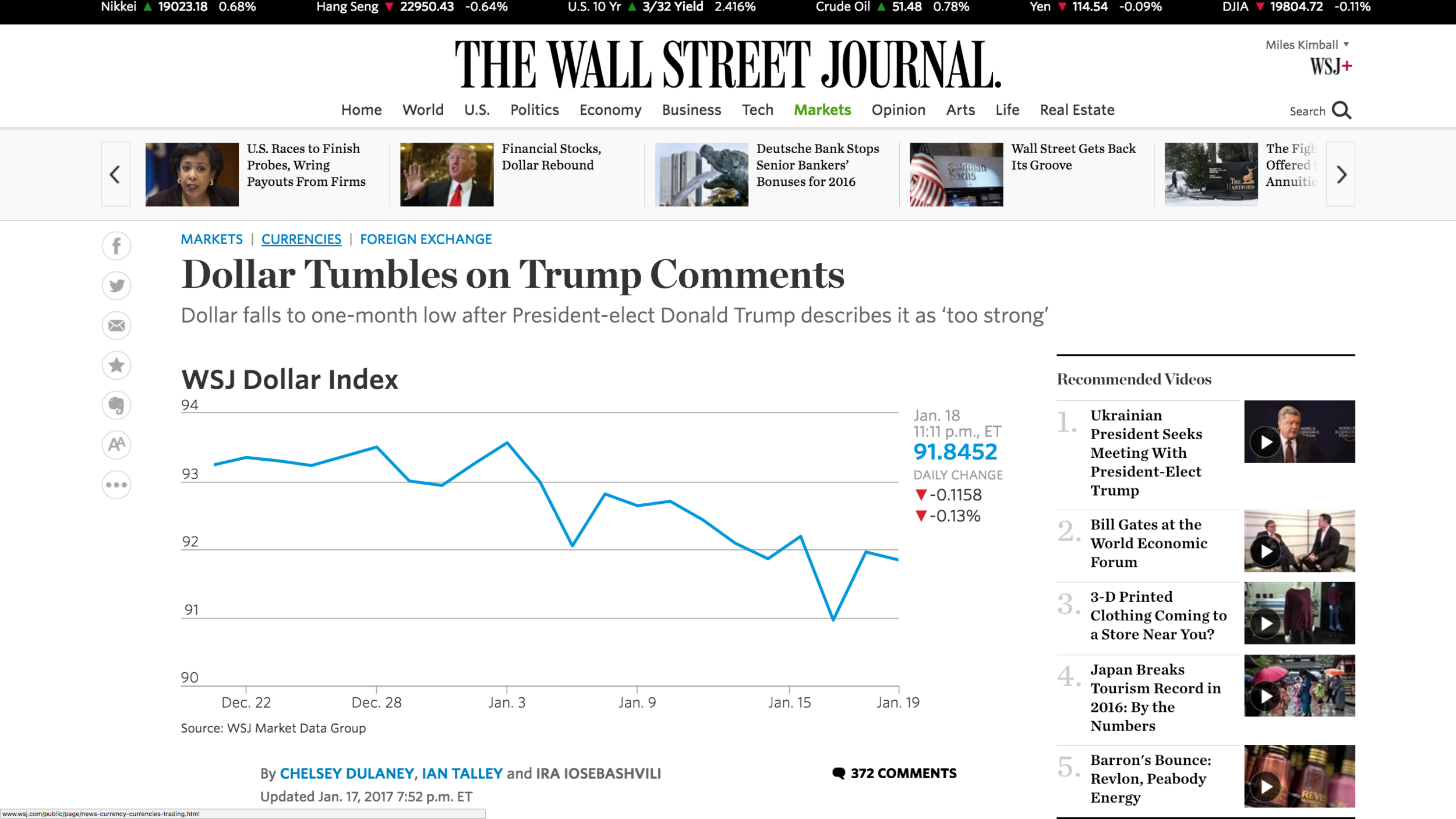

According to the recent reports, the Republicans in Congress want to cut the corporate tax rate to 20% and have it be "border adjustable, while soon-to-be President Donald Trump wants to cut the corporate tax rate to 15% and have the dollar depreciate. Let me leave aside the effects of cutting the corporate tax rate to focus on the effects of "border-adjustability" and dollar depreciation.

First, border adjustability. In the eurozone, where there is a fixed exchange rate of 1 between the member countries, relying more heavily on a value-added tax—for which international rules allow taxing imports while exempting exports from the tax—and less on other taxes, is understood as a way to get the same effect as devaluing to an exchange rate that makes foreign goods more expensive to people in a country and domestic goods cheaper to foreigners.

But in a floating exchange rate setup as the US has, most of the effects of border adjustment can be canceled out by an explicit appreciation in the dollar that cancels out the implicit devaluation from the tax shift. And indeed, such an appreciation of the dollar is exactly what one should expect. The reason is that the supply of US dollars available for the rest of the world to pay for net exports from the US is determined by the eagerness of those in the US to own more foreign assets minus the eagerness of those abroad to own more US assets. I explain this kind of reasoning in International Finance: A Primer. There is no reason to think that border adjustment dramatically changes the balance of those portfolio decisions. So the supply and demand for US dollars makes the price of the US dollar adjust to where the same amount of net exports will take place.

For a moment, suppose that border adjustment (or the other details of the tax change) instead of having little effect on the desire to hold US assets versus foreign assets made companies want to do more physical investment in the US and thereby hold more US assets as some hope. This would reduce the supply of dollars available to the rest of the world to pay for net exports to the US, and so would push the US dollar up to an even higher price than what would leave net exports fixed.

By contrast to border adjustment, which would tend to push the dollar up enough to cancel its effects, Donald Trump's wish for a lower price of the US dollar, if it happened, would stimulate net exports. Remarkably, just his talking about wanting a lower dollar seems to do a lot to make the dollar go down as he wants. Currency traders think that some kind of future policy supporting that decline in the dollar will come about. They may be wrong, in which case the dollar will return to a higher value in the future. This makes them want to get out of US assets, which pushes the dollar down now as a result of those traders thinking something will push the value of the dollar down in the future.

But if the future policy to justify a lower dollar price is not forthcoming, flows of portfolio investment will shift and the dollar will rise again. What could those future policies be? One possible way to push down the dollar for a few years time is loose monetary policy that lowers rates of return in the US, making foreign assets more attractive. When people in the US flee the low interest rates to buy foreign assets, they are providing extra US dollars to the rest of the world, which pushes down the price of the US dollar and raises net exports. However, too much loose monetary policy would eventually cause unwanted inflation.

A way to push down the value of the dollar and stimulate net exports for a much longer time is to increase saving rates in the US. This is easier than you might think. As I explained in my May 14, 2015 column "How Increasing Retirement Saving Could Give America More Balanced Trade":

I talked to Madrian and David Laibson, the incoming chair of Harvard’s Economics Department (who has worked with her on studying the effects of automatic enrollment) on the sidelines of a Consumer Financial Protection Bureau research conference last week. Using back-of-the-envelope calculations based on the effects estimated in this research, they agreed that requiring all firms to automatically enroll all employees in a 401(k) with a default contribution rate of 8% could increase the national saving rate on the order of 2 or 3 percent of GDP.

Under such a policy, people would not have to save more. But it would be the easy, lazy thing to do to save more. As greater saving pushed down US rates of return, some of that extra saving would wind up in foreign assets, putting extra US dollars in the hands of folks abroad, so they would have US dollars to buy US goods. This effect can be enhanced if the regulations for automatic enrollment are favorable to a substantial portion (say 30%) of the default investment option being in foreign assets.

Note that an increase in US saving would tend to push down the natural interest rate, and so needs to be accompanied by the elimination of the zero lower bound in order to avoid making it hard for monetary policy to respond to recessions. Fortunately, tools are readily available to eliminate the zero lower bound. See "How and Why to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound: A Reader's Guide."

It is worth noting one other difference between a policy of encouraging saving in this way and "border adjustment" for corporate taxation (besides the fact that encouraging saving will do the trick while border adjustment is unlikely to work). Border adjustment, by likely causing the dollar to look more expensive and other currencies to look cheaper, would tend to lower the dollar net worth of those who have substantial assets in other countries. By contrast, increasing US saving, by likely causing the dollar to look less expensive and other currencies to look more expensive, would tend to increase the dollar net worth of those who have substantial assets in other countries. So the policy that will actually work is also more in Donald Trump's pecuniary self-interest.

Addendum: Of course the US government could have a program of regularly buying large quantities of foreign assets assets directly. But such a blatant move would raise a much bigger storm of international protest than encouraging Americans to save more in an internationally diversified way. The governments of much smaller economies, such as Switzerland, Sweden, Denmark and Israel frequently do this--often through their central banks as a part of monetary policy. But China has come under a lot of criticism for this as "currency manipulation" even when it was trying to keep the yuan from rising rather than trying to make the yuan fall. Now that economic forces would make the yuan fall without government intervention, the Chinese government is afraid enough of international criticism and retaliation if the yuan falls that it is selling foreign assets rather than buying. It is possible that Donald Trump would be willing, perhaps even relish, the international criticism as a currency manipulator and so be willing to do it. But why take such a fraught route when it is so easy to change international capital flows and help Americans prepare for retirement at the same time? This, too, would occasion some international criticism as currency manipulation, but it helps a lot that it has another purpose as well. I predict that criticism would die down to a modest level relatively quickly--except from those who take the lower bound on interest rates as given and so view a further decline in the natural interest rate as a threat to the power of monetary policy.

One other minor problem with a regular US government program of buying foreign assets is that it requires either a budget surplus (as the Chinese government has had) or further borrowing. Further borrowing to raise funds to buy foreign assets is certainly possible, but allows the program to be challenged when the debt limit is reached (unless the debt is calculated on a net basis rather than simply in terms of outstanding liabilities).

Note: David Zervos points out that border adjustment raises revenue to offset revenue lost by the reduction in the corporate tax rate and by shifting away from taxing foreign corporate income directly. This is true as long as imports exceed exports so that the extra taxes due to imports exceed the cost of the tax break for exports. And precisely because border adjustment is likely to be ineffective at reducing the trade deficit, the excess of imports over exports would be likely to continue, and so would the net revenue produced by border adjustment.

Coda and Chorus: In October 2012, I wrote this in "International Finance: A Primer":

An Easy Policy to Restore America’s Industrial Heartland (Including Key Swing States). It is not likely that many people will actually be persuaded by my portfolio advice, so let’s think of a policy that really would increase the amount of foreign assets that Americans buy and so increase our exports and reduce our imports. David Laibson and his coauthors have found that in retirement accounts, people often stay with the default contribution level and allocation to different assets, even if they are allowed to change the contribution level and allocations of contributions to different assets by going through a little paperwork. There are at least two reasons for this. One is that people are sometimes a little lazy–or to be more charitable, perhaps scared of financial decisions. That makes them want to do nothing. The other reason people often stick with the default settings for their retirement accounts is that they think (unfortunately wrongly for the most part right now), that their company, or maybe the government has carefully thought through how much they should be putting aside and what they should be financially investing it in.

So imagine that the government establishes a regulation that employers all need to have a retirement saving account and have a relatively high default contribution level. The employers are not required to match it. And employees can get out of making any contributions just by doing a little paperwork. But many, many employees won’t change the default contribution. So this simple regulation could dramatically raise the household saving rate in America. Assuming the government keeps its budget deficits on the same path as it otherwise would, that would also raise the national saving rate. A higher national saving rate would make loanable funds more plentiful at any real interest rate, making a surplus of loanable funds at a high real interest rate and so drive down the real interest rate. With real interest rates low in the United States, Americans would start thinking of buying more foreign assets that earn higher interest rates, and foreigners would be less likely to buy low-interest-rate American assets. (How much people want foreign assets is only somewhat independent of rates of return, not totally independent. A big enough interest rate differential will lead people in both countries to shift.) With Americans buying more foreign assets and foreigners buying fewer American assets, the flow of dollars has shifted outwards. Something has to happen to recycle those dollars. That something is a change in the exchange rate that increases net exports. And it has to increase net exports by the same amount as the change in the flow of dollars for asset purchases.

Indeed, following the tradition of calling the flow of dollars for intentional asset purchases net capital outflow, we can say that net exports would have to equal net capital outflow. More precisely, the net flow of dollars for anything other than buying goods and services has to be exactly balanced by a countervailing net flow of dollars that is about buying goods and services. And except for short periods of time, the net flow of dollars for purposes other than buying goods and services has to be intentional; it won’t take long before unintentional movements get undone by recycling.

Now suppose that the government wants to increase net exports even more than was accomplished by mandating that all employers provide retirement savings accounts and setting a high default contribution level for retirement savings accounts. The government could simply add the regulation that the default asset allocation would be, say, 40% in foreign assets. That would dramatically increase the buying of foreign assets relative to what would be likely to happen otherwise (at least in the United States with current attitudes toward foreign assets). That would further increase net financial capital outflow from the United States, and lead to exchange rate adjustments that would further raise net exports to recycle those dollars back to the United States.

Paper Currency Deposit Fees as Unrealized Interest Equivalents

Note: for background to this post, see "How and Why to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound: A Reader’s Guide."

The Fed is allowed to charge fees for transactions at the cash window, but these fees must be reasonably closely related to actual expenses the Fed incurs. In negative interest periods, the Fed would incur an expense when banks with access to the Fed's cash window withdraw paper currency and then redeposit it after an intervening period of negative interest rates for marginal reserves and negative interest rates for the Treasury bills the Fed holds in its portfolio.

Negative interest rates simply mean that the lender pays the borrower rather than the borrower paying the lender. When banks withdraw paper currency, in an immediate sense they are reducing their balances in reserves, and therefore depriving the Fed of the payments it would otherwise receive as the borrower given negative interest on reserves--or in the Fed's reverse repo program acting as a substitute for reserves. (See "How the Fed Could Use Capped Reserves and a Negative Reverse Repo Rate Instead of Negative Interest on Reserves.")

On a rainy November afternoon after our two presentations at the Swiss National Bank, Ruchir Agarwal (my coauthor for "Breaking Through the Zero Lower Bound") and I wandered the streets of Zurich, and finally sought refuge in a coffee shop. There we pursued Ruchir's intuition that ultimately led to the insight that the paper currency deposit fee can be considered a way of making up for the negative interest that (aside from that) doesn't happen for paper currency, in an accounting sense.

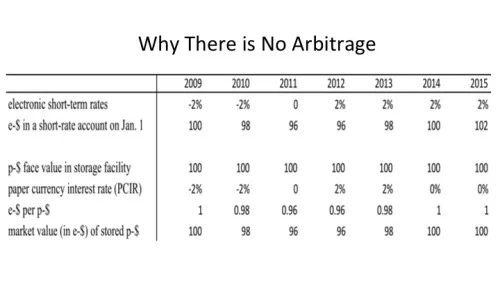

For cash taken out right at the beginning of a negative-interest-rate period, the equivalence between the paper currency deposit fee and unrealized interest is easiest to see. Consider the table above, from the Powerpoint file "21 Misconceptions about Eliminating the Zero Lower Bound (or Any Effective Lower Bound on Interest Rates)." If electronic, safe, short rates (such as the rates on reserves or Treasury Bills) are running at -2%, the same rate of return for paper currency can be engineered by having the electronic equivalent value of $100 face value of paper currency decline by 2% per year, until the level of electronic, safe, short rates changes. But from the legal perspective taken here, instead of thinking of the value of paper currency departing from par, each banknote (that is, each piece of paper currency) is thought of as having attached to it by an invisible umbilical cord a liability called an unrealized interest equivalent (UEI). The unrealized interest liability is owed to the central bank by the bearer of that banknote.

The image I have of the UEI is like a daemon in the book and movie The Golden Compass—a daimon standing beside, perched upon, or hovering in the air above the person whose daemon it is. There is a Wikipedia page for "Daemon," which describes them this way:

A dæmon /ˈdiːmən/ is a type of fictional being in the Philip Pullman fantasy trilogy His Dark Materials. Dæmons are the external physical manifestation of a person's 'inner-self' that takes the form of an animal. Dæmons have human intelligence, are capable of human speech—regardless of the form they take—and usually behave as though they are independent of their humans.

image source

In the Golden Compass, the daemon cannot be separated very far from the person it belongs to without great trauma to both the person and the daimon itself.

In the case of negative interest rates, the paper currency deposit fee weighing on the banknote (e.g. about 2% at the beginning of 2010 and about 4% at the beginning of 2011 in the example above) is exactly equal to the interest that would have been owed to the central bank as borrower if the banknote had been held since the beginning of the negative interest rate period. (The analogy to a daemon perched on a banknote is inexact: the UEI would not be the "inner-self" of the banknote.)

But what if a bank withdraws paper currency some time into the negative interest rate period, or even after interest rates have turned positive but cumulative interest since the beginning of the negative interest rate period is still in the hole? Then that bank does not owe the negative interest from before it withdrew the cash. A good way to avoid charging a private bank negative interest on paper currency that it doesn't owe—while making it easy to keep track of things—is for the central bank to have the banknote owe that interest but provide a preemptive refund to the private bank of the interest it didn't accrue. This is a nice way of looking at why it is appropriate for the amount a private bank is charged in its reserve account for cash withdrawals to be reduced by the amount of the paper currency deposit fee; the deposit fee at that point represents a UIE the bank doesn't owe since it hasn't had the paper currency out up to that point.

By giving the private bank a preemptive refund, the private bank then does owe the full UIE for the banknote accumulated since the beginning of the negative interest rate period. This full UIE from the beginning of the negative interest episode depends only on the date and not on when the bank withdrew it, avoiding the need for complex record keeping.

By the way, one thing I like about the legal argument here using the concept of unrealized interest equivalents is that it cannot justify an engineered rate of return on paper currency any lower than the interest rate on marginal reserves. Therefore, using this as a legal basis for a time-varying paper currency deposit fee provides protection against confiscatory reduction in the value of paper currency; paper currency can have a negative rate of return, but no more negative than the last dollar of reserves. That is enough to keep paper currency out of the way of a robust negative interest rate policy, but does not disadvantage paper currency in its rate of return relative to money in the bank.

Reparation and Deterrence

In section 10 of his 2d Treatise on Government: On Civil Government," John Locke distinguishes between deterrence and reparation:

Besides the crime which consists in violating the law, and varying from the right rule of reason, whereby a man so far becomes degenerate, and declares himself to quit the principles of human nature, and to be a noxious creature, there is commonly injury done to some person or other, and some other man receives damage by his transgression; in which case he who hath received any damage, has, besides the right of punishment common to him with other men, a particular right to seek reparation from him that has done it: and any other person, who finds it just, may also join with him that is injured, and assist him in recovering from the offender so much as may make satisfaction for the harm he has suffered.

However, if one takes a stochastic perspective, what is needed for proper reparation can do most of the work of deterrence. The key idea is that since the perpetrator of a particular harm—say a theft—is not always detected, the perpetrator who does get caught should make restitution for all of the other chances shehe had to get away with it as well as restitution for the (realized) case of getting caught. In other words, the starting point should be reparations equal to (1/p) * (harm of offense), where p is the probability of getting caught. This makes the expected gain for a criminal and the expected loss for a victim zero.

This starting point raises many issues:

First, it is not fair for bumbling criminals who often get caught to be paying the freight for clever criminals who seldom get caught. Thus, the multiple damages factor (1/p) needs to be based on a probability specific to a type of crime and to a type of criminal. In other words, by this logic, types of criminals known to be more clever and therefore to be caught less often should pay a higher multiple of the damages.

Second, if the probability of detection is too low, many perpetrators will be partially judgment-proof: genuinely unable to pay the full amount of (1/p) * (harm of offense). Also low detection probabilities create unfairness between individual perpetrators within the same type: some get lucky and get away with it, while others get caught. So higher detection probabilities are better. Given the value of a higher detection probability, perpetrators can legitimately be required to pay their share (multiplied by 1/p) of the costs of better detection as well as of other costs of enforcement. Note that charging perpetrators for the costs of detection and enforcement enhances deterrence.

Third, the deadweight loss to society of detection and other aspects of enforcement is greater if people do not take reasonable crime-prevention precautions, such as locking their doors. Thus, there should be some incentive for people to take basic crime-prevention precautions. Insurance is a great way to organize compensation for victims that both reduces risk for victims and provides appropriate incentives for crime prevention. People get compensated immediately for their loss—whether or not the perpetrator is caught—if they have been making basic efforts toward crime-prevention. Then when multiplied recovery is made from a perpetrator, the agency providing insurance gets the part of that money that was not needed to pay for detection and other aspects of enforcement. (The insurance agency's taking over the right of recovery is called "subrogation.") If someone has failed to make basic efforts toward crime prevention, they retain the right of recovery, but get nothing if no perpetrator is caught in that instance.

Finally, as discussed at some length in Robert Nozick's Anarchy, State and Utopia, the problem of people being partially judgment-proof can justify some penalties for taking risky actions that may harm others. That is, in many cases it can be reasonable to take as the starting point not (1/probability of detection) *(harm of offense), but (probability of harm given the risky action/probability of detection) *(magnitude of harm if it occurs). This modification also makes sense from a stochastic perspective.