Link to Wikipedia article on Mario Draghi

Mario Draghi gave a remarkable interview on October 31, 2015, labeled on an official webpage of the European Central Bank as “Interview with Il Sole 24 OreInterview with Mario Draghi, President of the ECB, conducted by Alessandro Merli and Roberto Napoletano.” I am grateful to Mike Bird and JP Koning for alerting me on Twitter to the importance of this interview.

To emphasize the points Mario Draghi is making about the role of various policy tools going forward, I have organized under my own headings what I consider the passages from the interview that I consider most important in their application to the future and to other central banks as well as the ECB. Mario Draghi has been head of the European Central Bank during a crucial period of time; I omit the parts of the interview focused primarily on reviewing that history, and focusing on the eurozone-specific issues.

To preview what is below, I include the Q&A about quantitative easing primarily as context. In the discussion of negative interest rates, Mario Draghi’s statement that

- The lower bound of the interest rate on deposits is a technical constraint and, as such, may be changed in line with circumstances.

is especially important. Compare this to the exact words of the statement I have urged central bank officials to make:

From a technical point of view, we know how to eliminate the zero lower bound.

On the truth of that statement, see my IMF Working Paper with Ruchir Agarwal, “Breaking Through the Zero Lower Bound,” which came out on October 23, 2015. (Also see my bibliographic post “How and Why to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound: A Reader’s Guide.”)

Mario Draghi makes many other important points in the interview with which I am in strong agreement:

- international monetary policy coordination is not essential; it is OK if each central bank takes care of its own jurisdiction

- government investments are the safest type of fiscal policy, but good government investments can be hard to find

- supply-side reform is important; appropriate stimulative monetary policy is helpful to supply-side reform or in some cases neutral for supply-side reform

Here are the parts of the interview focusing on these issues:

Quantitative Easing

Q: You have always said that this outcome depends on the full implementation of your monetary policy and you have added on a number of occasions that there is flexibility in your asset purchase programme in terms of its size, composition and duration. You have also said that the next meeting on 3 December 2015 is when you will “re-examine” these aspects. The financial markets read this date as being decision time for the ECB. Is this interpretation correct? Have you started to consider the relative merits of these three types of action, which could have different effects? Do you envisage using them simultaneously?

Mario Draghi: If we are convinced that our medium-term inflation target is at risk, we will take the necessary actions. In the meantime we are assessing whether the change in the underlying scenario is temporary or less so. Moreover, after the meeting in Malta, we asked all the relevant committees and ECB staff to prepare analyses of the relative effectiveness of the different options for the December meeting. We will decide on this basis. We will see whether a further stimulus is necessary. This is an open question. The programmes that we have put together are all characterised by their capacity to be used with the necessary flexibility.

Negative Interest Rates

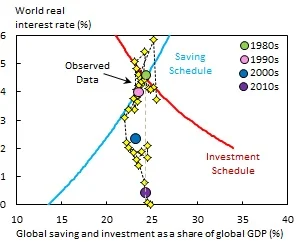

Q: However, for the first time you mentioned a cut in the ECB’s bank deposit rate and you said that “things have changed” since you had stated that -0.20% was the minimum lower bound. Can you explain what has changed?

Mario Draghi: The circumstances informing the decision to reduce the bank deposit rate to its current level actually consisted of a macroeconomic framework that has since changed. The price of oil and the exchange rate have changed. I would say that the global economic situation has changed. The interest rate on deposits could be one of the instruments that we use again. Now we have one more year of experience in this area: we have seen that the money markets adapted in a completely calm and smooth way to the new interest rate that we set a year ago; other countries have lowered their rate to much more negative levels than ours. The lower bound of the interest rate on deposits is a technical constraint and, as such, may be changed in line with circumstances. The main test of a central bank’s credibility is – as I have said before – the ability to achieve its objectives; it has nothing to do with the instruments.

Q: So, you see cutting the bank deposit rate as an instrument that can be used at the same time as the amendments to QE?

Mario Draghi: I would say that it is too early to make that judgement.

Q: In Malta, you also said you had discussed “some other monetary policy instruments”. What did you have in mind?

Mario Draghi: It would be too early at this stage to restrict the menu of instruments that will be assessed by the relevant committees and ECB staff. The existing menu is nevertheless extensive – you only have to look at what has been done in the past three years. However, it is too early to say in any case that “this is the menu” and that “there is nothing to add”.

International Monetary Policy Coordination

Q: You spoke earlier about the global macroeconomic environment which is changing. The Vice Chairman of the Federal Reserve System, Stanley Fisher, said that the Fed today takes much greater account of international factors than it did up until a few years ago. Is this true of the ECB as well? And does the Fed’s delay in starting to raise rates influence in some way your decisions, considering that the exchange rate is not a policy target?

Mario Draghi: As I said, external circumstances, the assumptions underlying our forecasts, are important because they influence inflation expectations, and therefore the profile of the return towards price stability and of the growth rate. They form part of the set of information that we, like the other policy-makers, use to take our decisions. As far as the Fed is concerned, there’s no direct link between what we are doing and what they are doing. Both central banks have their mandate defined by the jurisdiction in which they operate, for them it’s the United States, for us it’s the euro area.

Fiscal Policy

Q: In Lima you said that high-debt countries had to prepare for the day when they suffer from the impact of higher yields. At the same time, these countries suffer but also from the fact that inflation is very low, making debt reduction complicated. Isn’t this an even more serious risk? In Europe an increase in yields is not imminent, while too low inflation is making itself felt.

Mario Draghi: Low inflation has two effects. The first one is negative because it makes debt reduction more difficult. The second one is positive because it lowers interest rates on the debt itself. The path on which fiscal policy has to move is narrow, but it’s the only one available: on the one hand ensuring debt sustainability and on the other maintaining growth. If interest rate savings are used for current spending the risk increases that the debt becomes unsustainable when interest rates go up. Ideally, the savings are instead spent on public investments whose rates of return permit repayment of the interest when it rises. Growth is maintained today and future public finances are not destabilised when rates go up.

Obviously it’s not simple because, as we know, there aren’t many public investments with a high rate of return.

Supply-Side Reform

Q: Precisely on the subject of fiscal policy, there’s a lot of discussion in Europe at the political level. You are one of the first to use the expression “fiscal compact” in the European debate. Do you think now, looking back, that the degree of budget restrictions in the euro area was too strong after the crisis, in other words that there has been excessive austerity which has held back the recovery in the euro area?

Mario Draghi: First of all, there are countries which don’t have the scope for fiscal expansion according to the rules which we have given ourselves. Secondly, where this is possible, fiscal expansion must be able to take place without harming the sustainability of the debt. The high-debt countries have less scope to do this. But the fiscal space is not a fact of nature, it can be expanded, even a high-debt country can do it. How? By making the structural reforms which push up potential output, the participation rate, productivity, all factors which substantially boost the potential for future tax revenues. Increasing revenues on a permanent basis expands the possibilities for repaying debt tomorrow and at the same time creates the conditions for fiscal expansion today. The structural reforms are not popular because they involve paying a price today for benefits tomorrow, but if the government’s commitment is real and the reforms are credible, the benefits are gained more quickly and they include fiscal space.

Stimulative Monetary Policy and Supply-Side Reform are Complements or Separable, Not Substitutes

Q: The ECB’s Governing Council stands ready to increase monetary stimulus, should this be necessary. Your critics claim that this reduces the incentive to implement reforms.

Mario Draghi: I think that this is wrong for a number of reasons. First, if we look at the time frame of the main structural reforms implemented in the euro area over the past five years, it shows that this has no correlation with the level of interest rates on government debt in the countries concerned. Labour market reforms, for example, were implemented in both Spain and Italy when interest rates were already very low, and the same is also true in other cases. Second, the structural reforms cover a very wide range of areas. I do not believe, for example, that reform of the legal system has anything to do with interest rate developments. Third, recent experience shows that also when interest rates are high because a country’s fiscal credibility is threatened, this does not increase governments’ propensity to carry out reforms.

Q: How do structural reforms correspond to low interest rates?

Mario Draghi: Structural reforms and low interest rates complement each other: carrying out structural reforms means paying a price now in order to obtain a benefit tomorrow; low interest rates substantially reduce the price that has to be paid today. There is, if anything, a relationship of complementarity. There are also other more specific reasons: low interest rates ensure that investment, the benefits from investment and from employment, materialise more quickly. Structural reforms reduce uncertainty regarding macroeconomic and microeconomic prospects. Therefore, it is the opposite, rather than seeing an increase in moral hazard, I see a relationship of complementarity, of incentive. But it should never get to the point of having to consolidate the government budget when market conditions have become hopeless. Experience over recent years has shown that, in these circumstances, governments often make mistakes in designing economic policies, dramatically hike taxes and reduce public investment, without significantly reducing current spending, and postpone the structural reforms that require social consensus. In this way, they exacerbate the recessionary effects of the high interest rates and slow the fall of the debt-to-GDP ratio.

To conclude, in the euro area the markets do not typically influence the propensity of governments to carry out structural reforms; when this happens, because the governments have delayed the reforms for too long, and owing to the deterioration in the general conditions, the resulting economic policy action does not foster growth.