Dynamic Graph of Gay Marriage Rights in the United States

Today the Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage across the US.

Reblogged from vox.

A Partisan Nonpartisan Blog: Cutting Through Confusion Since 2012

Dynamic Graph of Gay Marriage Rights in the United States

Today the Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage across the US.

Reblogged from vox.

Here is a link to my 64th column on Quartz, “Radical Banking: The World Needs New Tools to Fight the Next Recession.” Among other things, this column gives a report about two amazing conferences in London about eliminating the zero lower bound.

The link above is to the post in Japanese, translated by Makoto Shimizu. You can find the English version here.

The link above is to the post in Japanese, translated by Makoto Shimizu. You can find the English version here.

The link above is to the post in Japanese, translated by Makoto Shimizu. You can find the English version here.

The link above is to the post in Japanese, translated by Makoto Shimizu. The English version can be found here.

The link above is to the post in Japanese, translated by Makoto Shimizu. The English version can be found here.

This is a fascinating discussion by Bruce Greenwald of

the difficulties of shifting people from working in sectors like agriculture and manufacturing where employment is declining because productivity is going up faster than demand,

the efforts of some countries to export this problem to other countries, and

the effect of these forces on interest rates, and therefore, implicitly, their interaction with the zero lower bound.

It is very interesting to think about how these issues could play out if there had been no zero lower bound and their had been aggressive negative interest rate policy. Regardless of the low interest rates, it still doesn’t work to have more manufacturing output that people want to buy any more than it makes sense to have more food grown than people can possibly eat. So at the end of the day, manufacturing capacity would get high enough to put a brake on further investment in manufacturing despite very low interest rates. Either people will start consuming a lot more because of the low interest rates, or more likely there would end up being extra investment in something else. A good possibility is education. Education is a form of investment that can easily absorb a huge amount of resources simply in student time, even if in the future it doesn’t need much in the way of buildings or professors because it has gone electronic. Standard human capital theory suggests that a low enough long-run real interest rate can have a big effect on the amount of education chosen.

I want to try to smoke out what is problematic about the minimum wage. A minimum wage is saying a firm that wants to make a job offer and a worker who wants to accept that offer are not allowed to make a deal.

1. To clarify things, an interesting variant of a minimum wage policy that would avoid this would be to say that the minimum wage applies only to existing jobs, not to new hires. This limits the minimum wage increase to the already existing employment relationships that I think are the foundation of people’s intuition that the minimum wage is a good thing.

2. Going a little further, to avoid distortion, it might be necessary to allow a firm and a worker to agree to a contract that opts out of any possible higher minimum wage in the future.

To make this policy more realistic, almost all distortion can probably be avoided even if there is a time limit of a year or two from the moment of hiring on how long a contract can opt out of the minimum wage.

3. Going the other direction, it is interesting to consider a minimum wage that applied only to new hires and not to existing employment relationships. I think few people would be in favor of such a minimum wage. It is interesting to consider why.

Summing Up: Maybe there is a better way to lay things out: the objective is to separate out analytically the effect of the minimum wage on new hires from the effect of the minimum wage on existing workers.

Note: One can argue that telling someone shehe may not take a job a firm wants to give herhim will benefit other workers who do get jobs, but if that is the argument for a minimum wage, I would like to see it stated that baldly: “You must sacrifice and not take that job so that other workers can be paid more.”

This is a nice video of Clay talking about the benefits of religion. An atheist group complained about it. But they don’t understand:

“… an unintended effect is a real effect, which may be welcomed without prejudice to intended effects. … facing such an unintended effect and sensing the presence of an intrusive subjectivity, modernist historical criticism, like virtually all modernist criticism, catches itself in time, and muffles its inclination to join in the discussion as one might muffle one’s inclination to join in a laugh at a funeral. The critic may find the joke funny, but to laugh at it would interrupt the ceremony—or, in this instance, retard the collective enterprise. Postmodern criticism—going nowhere, we might say—feels no such inhibition. More important, it has time to linger over distractions and chance arrangements that, like a sunset, are intended by nobody, but may lift the spirits of anybody willing to be led outdoors for a look.”

– Jack Miles, in Christ: A Crisis in the Life of God, pp. 331-332.

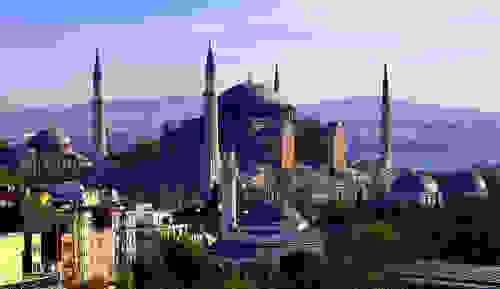

The day before the Turkish election on June 7, I posted a link to the Economist’s editorial “Why Turks Should Vote Kurd: It Is the Best Way of Stopping Their Country’s Drift Towards Autocracy,” with the note

True democracy can be lost. Turks need to protect theirs.

So it was good news indeed when Turks voted resoundingly to stop Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s hopes to create a powerful presidency for himself.

I find myself again in full agreement with the Economist in its June 13th editorial “Sultan at Bay,” in which the editorial staff wrote:

The European Union, too, should do more. It was partly because Turkey’s membership talks, begun in 2005, seemed to go nowhere that Mr Erdogan drifted towards autocracy. Now that Turks have so thrillingly demonstrated their democratic credentials, the EU should revive the negotiations. There is also new hope that the age-old Cyprus problem might be solved (see article). Turkey matters hugely for the future of Europe. Resurrecting its aspirations for EU membership would be a fine reward for its admirable voters.

As I preached in my sermon the day of the Turkish election, “The Message of Jesus for Non-Supernaturalists,” including others in things that are working relatively well is one of the most powerful ways of making the world a better place. The European Union is far from perfect, but in a global context it counts as something that is working relatively well.

Extending the blessings of the European Union into the Middle East seems especially valuable in trying to foster stability in this volatile area of the world. It is a bit optimistic, but it is not too much to hope that from now on, electoral competition in Turkey will make the Turkish government more pro-Kurd, which could be especially valuable in shifting the balance in the Middle East in a favorable direction.

Stephanie Shimko interviewed me for the May 2015 issue of the Survey Research Center’s monthly newsletter at the University of Michigan. I thought I would share it. It used the same picture I use now as my avatar.

When we asked Miles Kimball how he became interest-ed in macroeconomics, he told us that it began in his second year of Harvard’s Economic PhD program. Miles referred us to his blog post “Why I am a Macroeconomist.” Miles’ dissertation contained three topics, which is usual for economic dissertations. His first topic was two-sided altruism (the economic consequences of children caring about parents, as well as parents caring about children) that was suggested by his professor Andy Abel. His classmate, Alan Krueger (who was later Assistant Secretary of the Treasury and head of the Council of Economic Advisers) suggested Miles’ second topic, efficiency wages. The third topic, precautionary saving, developed when Miles presented his economic history paper “Farmers Cooperatives as Behavior Towards Risk” in a seminar and his colleague, Greg Mankiw, told him it reminded him of a paper he had written on precautionary saving. Miles told us: “In each case, I just tried to write down the economic model that seemed sensible to me in that topic area, and found that each economic model had interesting implications.” We also asked Miles about his ongoing research questions. He gave us five of his critical research questions.

For the future, Miles said: “Going forward, in addition to continuing to pursue the kinds of questions I mention above, I want to pursue research that shows that I can back up key proposals I make on my blog, ‘Confessions of a Supply-Side Liberal’, with more formal academic arguments. And I would like to find time to lay out the methods I teach in my class on ‘Advanced Mathematical Methods for Dynamic, Stochastic Models’.” We asked if there were any exciting upcoming projects, and he responded: “My proposal for making deep negative interest rates possible seems to be getting some traction. I am looking forward to some conferences on this, and visits to the central banks of Sweden, Norway, and New Zealand this summer (as well as the Bank of Finland).” Miles also spoke to us about his work in subjective well-being: “Along with Dan Benjamin, Ori Heffetz, and other coauthors, I have published several papers in the American Economic Review about how subjective well-being data relate to the goal of measuring how well-off people are in the full range of things they care about. Dan and Ori and I attended a High Level Expert Group Workshop on Multidimensional Subjective Well-being in Turin last October; our basic approach was very well-received”. At the end of our session, we noticed how often his blog was central to his answers to our questions. He said: “My blog is both an important part of my professional career and a hobby. You can see there all kinds of other things going on in my life and things I am thinking about. On Sundays I alternate between blogging about religion and blogging about philosophy (so far, blogging my way through John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty). I frequently host guest posts on my blog, so it is not a one-man show.”

Thanks to Laura Overdeck for pointing me to these gifs.

Here is the full text of my 62d Quartz column, “The TPP would be great for America if Americans had been saving for retirement,” now brought home to supplysideliberal.com. It was first published on May 14, 2015. Links to all my other columns can be found here.

In the column, I write:

Using back-of-the-envelope calculations based on the effects estimated in this research, they agreed that requiring all firms to automatically enroll all employees in a 401(k) with a default contribution rate of 8% could increase the national saving rate on the order of 2 or 3 percent of GDP.

Here is a rough idea of the kind of simple calculation that could back that claim up:

If you want to mirror the content of this post on another site, that is possible for a limited time if you read the legal notice at this link and include both a link to the original Quartz column and the following copyright notice:

© May 14, 2015: Miles Kimball, as first published on Quartz. Used by permission according to a temporary nonexclusive license expiring June 30, 2017. All rights reserved.

It is no accident that US president Barack Obama asked for fast track trade promotion authority after he had faced his last election. Free trade is good for economic growth. Economic theory predicts that the value to consumers, workers and owners of firms gained from free trade outweighs the value lost. So why do so many politicians see free trade as toxic politically?

One reason rightfully given for the political toxicity of free trade is that the concentrated losers from free trade are more obvious, more vocal, and better organized than the widely dispersed winners from free trade. During recessions, another factor in the opposition to free trade is that people blame trade for what is primarily a failure of monetary policy or a failure of financial stability policy. When the poor in other countries are out of mind, a concern about the effect of free trade on the poor in one’s own country can be a reason to oppose free trade. And one can cogently worry that free trade might adversely affect sectors of the economy that start out being stunted by product market and labor market distortions more than the sectors of the economy that would be helped by free trade (one of the few things that can overturn the theoretical prediction that the value gained from free trade outweighs the value lost).

Yet despite all these factors, I wonder if many who think of themselves as opposing free trade are really opposed to trade deficits. Let me speak as if the home country at issue is the US, but a similar question can be asked for many countries. How many people would be against free trade if it were balanced trade in which people and firms in other countries buy just as much from Americans as Americans buy from them?

If trade were balanced, it would mean that every dollar of imports would be balanced by a dollar of exports. Intuitively, freer trade means that people in the US can do more of what they are best at and less of what they are worst at—but with this subtlety: in producing goods and services people in the US are better at almost everything than people in other countries. So to have balanced trade, out of all the things people in the US are better at, some at the bottom of the list of US advantage (whether in ability to produce quantity or to produce quality) have to be imported in order to give people in other countries the US dollars they need to buy the things near the top of the list of US absolute advantage.

All of this gets thrown off when trade is not balanced. How can that happen? To simplify, when Americans buy Chinese goods with borrowed Chinese yuan, while the Chinese people and the Chinese government save the US dollars they get instead of spending them on American goods, and Americans follow the same pattern with many other countries, then the US will run a trade deficit. Running a chronic trade deficit results in less employment in a way that goes beyond the business cycle.

What is the remedy for unbalanced trade? It isn’t trade restrictions. Regardless of trade restrictions, as long as Americans are borrowing more from other countries than they are borrowing from us, the simple fact that they are directly or indirectly (when doing the foreign exchange transaction) handing Americans their currency when they lend guarantees that one way or another Americans will end up spending more on foreign goods and services than the other way around. Thus, the equation is that if you borrow from foreigners, you will buy more from foreigners than they will from you. (I explain this principle more on my blog.)

For a country running a trade deficit as the US is, given open financial markets, the only way to get to more balanced trade is for the American people, American firms or the US government to save more, or for Americans to shift their net financial investments toward lending to foreigners.

It might seem that it would be hard to raise the US saving rate given the limited success of past attempts. But the conjunction of psychology and economics has identified a powerful and underappreciated lever for raising saving, waiting to be used. In remarkable research initiated by Brigitte Madrian (now a professor at Harvard’s Kennedy school) and continued with the help of many coauthors, it has been found that when people are automatically enrolled in 401(k)’s, they save a lot more than when they have to actively set up 401(k) contributions themselves. Some people opt out of doing that extra saving, but many don’t.

I talked to Madrian and David Laibson, the incoming chair of Harvard’s Economics Department (who has worked with her on studying the effects of automatic enrollment) on the sidelines of a Consumer Financial Protection Bureau research conference last week. Using back-of-the-envelope calculations based on the effects estimated in this research, they agreed that requiring all firms to automatically enroll all employees in a 401(k) with a default contribution rate of 8% could increase the national saving rate on the order of 2 or 3 percent of GDP.

The regulation I am talking about would not require any change to the rate at which firms match their employee’s contributions. One of the biggest benefits would be helping people arrive at retirement well prepared financially. But it would also have a major effect on the US trade balance. If the US ran smaller trade deficits, employment would go up beyond any particular business cycle. If Americans were saving too much and had too many available jobs tempting them to work too much, that wouldn’t be a good thing for them. But right now, in this economy, more jobs and more savings are appropriate, so it would help them.

Automatic enrollment in retirement savings plans is so powerful that some economists will worry that its spread will help exacerbate a global glut of saving. But if paper currency policy gets out of the way of the appropriate interest rate adjustments, financial markets will find the appropriate equilibrium. They will balance the supply and demand for saving, and companies will realize the extent to which an abundance of saving makes available the funds they need to dream big by creating new markets and technologies that the future of America depends on.

Both in law and in our less formal judgments of others’ actions and our own, we recognize the idea of “diminished capacity”: at the moment of doing the bad thing, not being able to think straight. But there are many things that predictably lead to not being able to think straight: alcohol, too little sleep, titanic anger, strong sexual arousal, etc. Because these predictably affect our judgment, we each bear a responsibility to make sure that at each moment we are either (a) avoiding such states at that moment or (b) set things up–say by prearranging many key things–so as to minimize any harm that might come from distorted judgments in those states. It is appropriate to hold people to account on that responsibility.

John Stuart Mill alludes to that principle in On Liberty “Chapter V: Applications,” paragraph 6:

The right inherent in society, to ward off crimes against itself by antecedent precautions, suggests the obvious limitations to the maxim, that purely self-regarding misconduct cannot properly be meddled with in the way of prevention or punishment. Drunkenness, for example, in ordinary cases, is not a fit subject for legislative interference; but I should deem it perfectly legitimate that a person, who had once been convicted of any act of violence to others under the influence of drink, should be placed under a special legal restriction, personal to himself; that if he were afterwards found drunk, he should be liable to a penalty, and that if when in that state he committed another offence, the punishment to which he would be liable for that other offence should be increased in severity. The making himself drunk, in a person whom drunkenness excites to do harm to others, is a crime against others. So, again, idleness, except in a person receiving support from the public, or except when it constitutes a breach of contract, cannot without tyranny be made a subject of legal punishment; but if, either from idleness or from any other avoidable cause, a man fails to perform his legal duties to others, as for instance to support his children, it is no tyranny to force him to fulfil that obligation, by compulsory labor, if no other means are available.

It would be too great a burden on freedom to punish people for not (a) avoiding states of impaired judgment if they might well be pursuing strategy (b) of arranging things careful so impaired judgment does no harm. But once someone has committed an offense under impaired judgment, the presumption that they are pursuing strategy (b) cannot be held as strongly.

Stepping back, one can consider the human condition in general as one of impaired judgment. Therefore, along the lines of strategy (b), it is our duty to set up social arrangements so that our impaired judgment causes as little trouble as possible. Foremost among such social arrangements is to avoid giving too much power to any one individual. Dictatorship is like drunkenness without any precautions.