Love's Review

David Love, whom I only now learn goes by “Dukes,” was a star student in my very advanced “Business Cycles” class at the University of Michigan. He went on to get a Ph.D. in Economics at Yale and become a tenured macroeconomics professor at Williams College. We have stayed in touch over the years, but had not corresponded recently. I share his email a few days ago with his permission:

Dear Miles,

After a week of continuously visiting and reading your blog, I thought I’d let you know that you’re providing a wonderful public service. There’s a gem in nearly every entry, and I’ve found myself eagerly returning to see whether you’ve posted anything new. If you want to know how influential a good blog can be, consider that I’ve read Chetty’s article on measuring risk aversion; your recent NBER paper on the fundamental aspects of well being; and I just ordered an exam copy of Weil’s textbook on Economic Growth – and all in the week since I started visiting Confessions of a Supply Side Liberal. I was especially touched by your sermon inspired by David Foster Wallace, and I sent it along to friends and family far removed from economics.

There are many economics blogs out there, but yours contains a rare mixture of fine writing, humanity, and Feynman’s pleasure of finding things out. Thanks for putting it out there!

Sincerely,

Dukes

Pedro da Costa on Krugman's Answer to My Question "Should the Fed Promise to Do the Wrong Thing in the Future to Have the Right Effect Now?"

In Krugman’s Legacy: Fed gets over fear of commitment, Pedra da Costa gives a nice summary of Paul Krugman’s view that the Fed needs to commit to overstimulate the economy in the future in order to stimulate the economy now. In a post back in June, I asked the question “Should the Fed Promise to Do the Wrong Thing in the Future to Have the Right Effect Now?” directing my question to Scott Sumner in particular. This was really a question about whether "Quantitative Easing" (see my post “Balance Sheet Monetary Policy: A Primer”) has an effect independent of how it changes people’s expectations about future safe short-term interest rates such as the federal funds rate. If buying long-term and risky assets has an independent effect, then with large enough purchases, the Fed can stimulate the economy now without committing to push the economy above the natural level of output in the future, as I discussed in “Trillions and Trillions: Getting Used to Balance Sheet Monetary Policy,” where the picture of a giant fan at the top of the post symbolizes the idea that a small departure from the way things work in a frictionless model, multiplied by huge purchases of long-term and risky assets, can have a substantial effect. In my view, Krugman made an error by trusting a frictionless model too much. In other contexts, economists are suspicious of frictionless models that make extremely strong claims if applied uncritically to the real world, as I discuss in “Wallace Neutrality and Ricardian Neutrality.”

On the question of how the world works, “Wallace Neutrality and Ricardian Neutrality” links to Scott Sumner’s answer, while “Trillions and Trillions: Getting Used to Balance Sheet Monetary Policy,” links to Noah Smith’s answer. Scott, Noah and I are on record against the frictionless model behind Paul Krugman’s views. I have tried hard to convince Brad DeLong on this issues, as you can see in “Miles Kimball and Brad DeLong Discuss Wallace Neutrality and Principles of Macroeconomics Textbooks.” My sense is that Brad has come around to some degree, though that may be just wishful thinking on my part.

There is a technical name for what I am talking about in this post–a name you can see above: “Wallace neutrality.” For some links on Wallace neutrality, see my post “‘Wallace Neutrality’ on wikipedia.”

Let me be clear that this scientific issue will become most important when the economy has recovered. At that some, I forecast that some voices will call on the Fed to “keep its commitment” to leave interest rates low even after the economy has recovered “in order to maintain credibility for stimulative promises in the more distant future.” The Fed needs to be able to point back to a clear record of statements showing that it never made such a commitment. Those most concerned about inflation (“inflation hawks”) in the FOMC (the Federal Open Market Committee, which is the monetary policy decision-making body in the Federal Reserve System) should be particularly worried about this, and should make clear in every speech that the Fed has not made any precommitment to overstimulate the economy in the future.

If large scale asset purchases have an independent effect on the economy (not working through expectations), building up a track record of following through on promises to overstimulate the economy is unnecessary. In other words, if the real-world economy does not obey Wallace neutrality, situations in which the federal funds rate and the Treasury bill rate are close to zero can be dealt with by purchasing other assets, instead of by promises of future overstimulation.

My recommendation is that the Fed continue to insist that it is only predicting its future policy, not precommitting. Even better would be to make clear that the Fed will continue very vigorous stimulative policy until output is again fully on track to reach its natural level, but is making no commitment to push the economy above its natural level of output (unless doing so is necessary for price stability). If I understand correctly, recommendations by Market Monetarists that the Fed should announce that it is targeting nominal GDP are in this spirit.

A List of Macro Blogs from Gavyn Davies →

This blog, Confessions of a Supply-Side Liberal, made it onto Gavyn Davies’s list of macro blogs to follow.

Stephen Donnelly on How the Difference Between GDP and GNP is Crucial to Understanding Ireland's Situation →

Ireland is in trouble. But outside Ireland, many economists think it is doing fine. Why? Stephen Donnelly argues that part of the answer turns on the difference between Gross Domestic Product and Gross National Product. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the value of goods and services produced within a country each year or quarter. Gross National Product (GNP) is the value of goods and services produced by the labor, capital and other resources owned by citizens of a country each year or quarter. For most countries, GDP and GNP are close to each other, but Ireland has attracted so much foreign investment that a large share of its capital stock in owned by foreigners. Thus, Ireland’s GNP is much lower than its GDP.

The presence of the foreign-owned capital raises wages in Ireland, so it is a good thing. But the income from the foreign-owned capital itself does not belong to Irish citizens, and so is not much help when it comes to handling the debt of the Irish government–especially since the Irish government needs to keep the promise to tax foreign-owned capital lightly that it made in order to attract foreign investment.

Energy Imports and Domestic Natural Resources as a Percentage of GDP

Much is written and said about the impact of energy imports and natural resources on output. But a basic fact makes it hard for energy imports and natural resources to matter as much as people seem to think they do: natural resources account for a small share of GDP–on the order of 1% = .01, and energy imports measured as a fraction of GDP are also on the order of 1% = .01. Even a 20% increase in the price of imported oil, for example, should make overall prices go up something like a .01 * 20% = .2%. It should take a huge increase in the price of oil to make overall prices go up by even 1%. Am I missing something?

It is a little dated, but here is what I found online about oil imports as a percentage of GDP. (I’ll gladly link to a more recent graph instead if there is one.) 2% of U.S. GDP is near the high end for the value of our oil imports in the past. And here are World Bank numbers for factor payments to natural resources as a percentage of GDP.

Cross-National Comparisons of Tax and Benefit Systems and Economic Behavior

Question from tommlu

Hi. I’m an undergraduate in my senior year, and I was wondering if you could any topics for an economic thesis, particularly in the area of taxation. Let me say that I am unconvinced that taxes has an effect on economic growth in the short run or the long run. There’s no doubt that taxes create a disincentive to work, but is that effect really so large as to decrease overall economic activity (productivity, demand, income,). If you could offer any suggestions for me, I would love to hear them. Thanks.

Answer

To me, the more interesting question is the long-run question. Here, I think there is something very useful you could do in an undergraduate thesis. Tax and benefit systems of different countries are complex enough that it is not easy to research all the details to compare how different tax and benefit systems lead to different effects. (I have seen this done more comprehensively for tax and benefit policies that would affect retirement decisions than for tax and benefit policies for younger workers). Doing thorough case studies of the tax and benefit systems of various countries and looking for the predicted effects would be a great service. For example, do many of the French take August off because of the details of their tax and benefit system? Is there something about Germany’s tax code and benefit code that helps explain why so few German women work? Don’t forget advanced Asian economies, such as Japan.

You would have the most impact if you concentrate first and foremost on providing clear summaries of how the tax and benefit codes of different countries work and what the details are. I know I would learn a lot from that. I think most economists would.

What I am suggesting might have been impossible before Google Translate, but nowadays, your computer will give you a translation that is probably good enough to figure out most of what is going on.

Matthew O'Brien: How Much is a Good Central Banker Worth? →

This is a very interesting article. In relation to what Matthew writes, let me say that Ben Bernanke is a superstar central banker in my book. It is a mistake to judge central bankers by a standard of perfection. Central banking is too hard for that. Ben has done a great job in difficult circumstances, as can be seen in David Wessel’s book In Fed We Trust. My guess is that Ben’s biggest mistakes as a central banker have come from deferring too much to other views that were less on-target than his own. Although making monetary policy decision-making less centered on the Chairman of the Fed is the right thing for the long-run future, I think we would have had better monetary policy in the last few years had Ben trusted his own judgment more and asserted himself more strongly. Ben’s mistakes of intellectual humility are the kinds of mistakes a serious seeker of the truth makes.

Books on Economics

Two questions: One, I am interested in your recommendations about a book/articles to read list for those lay-persons interested in the study of economics. I am attorney by training but love to read about differing theories on economics. I am a bit on the progressive side in my politics and so found your definition of “supply-side liberal” interesting. Second, your view on FDR and Depression-era economic policies and what it took for the U.S. economy to recover during that time. Thanks.

Answers: On what non-economists should read about economics, my first reaction is that the economics blogosphere is the place to go. For example, if you want a discussion accessible to non-economists of current economic disputes, Noahpinion.com does a good job. I have been telling Noah for some time that as part of his academic career he should become a historian of modern macroeconomic thought. You can see his talent for that in his blog.

My second reaction is that some economics textbooks are truly excellent and good for anyone to read even if they are not taking a class. I am currently reading some of the macroeconomics chapters from Tyler Cowen and Alex Tabarrok’s Modern Principles of Economics. It is a great read. I agree with this review on Amazon:

This is one of the most readable textbooks I have ever encountered. The writing is amazingly interesting given that it is a general, core subject. The book includes many very up-to-date samples and reads almost like a magazine in places.

I need to read a lot more to decide whether to use it for my class, but I am definitely tempted.

At the next level up, I love David Weil’s textbook Economic Growth. This is the truly important stuff in economics. You can see what I learned from (the first edition of) this book in my post “Leveling Up: Making the Transition from Poor Country to Rich Country.”

My third reaction is to look at what I have actually read. (In conversation, economists often use the words “revealed preference” to express the idea “Watch what I do, not what I say.”) I have kept a list of books I have read since 1995. I have been planning to write posts based on that list at some point. Let me use your question as an occasion to do a basic post on the economics slice of my book list.

Only a small fraction of the books I read are economics books. Here are the economics, economic policy and business books on the list, with the month I finished reading each. For the most part, I have linked to the most recent edition I found. I should say that I disagree with two of the books below in important respects: The Paradox of Choice by Barry Schwartz and Happiness by Richard Layard, although these are very interesting books. Let me also say that Thorstein Veblen is a terrible prose stylist, so I doubt you would enjoy reading The Theory of the Leisure Class.

- The Unbound Prometheusby David S. Landes (4/97)

- The Lever of Riches by Joel Mokyr (5/97)

- The Wealth and Poverty of Nations by David Landes (5/98)

- Luxury Fever by Robert H. Frank (3/99)

- The Evolution of Retirement by Dora L. Costa (8/99)

- The Return of Depression Economics by Paul Krugman (9/01)

- The Wealth of Man by Peter Jay (10/01)

- Digital Dealing by Robert E. Hall (11/02)

- The New Culture of Desire by Melinda Davis (8/03)

- The Rise of the Creative Class by Richard Florida (8/03)

- The Overspent American by Juliet Schor (12/03)

- The Matching Law by Richard J. Herrnstein (3/04)

- The Sense of Well-Being in America by Angus Campbell (4/04)

- Macroeconomics (5th ed.) by N. Gregory Mankiw (4/04)

- The Progress Paradox by Gregg Easterbrook (5/04)

- False Prophets: The Gurus Who Created Modern Management…by James Hoopes (5/04)

- The Paradox of Choice by Barry Schwartz (7/04)

- The Elusive Quest for Growth by William Easterly (2/05)

- Growth Theory by David Weil (3/05)

- Happiness by Richard Layard (3/05)

- The Joyless Economy by Tibor Scitovsky (5/05)

- The Winner-Take-All Society by Robert Frank and Philip Cook (8/06)

- The Theory of the Leisure Class by Thorstein Veblen (9/06)

- The 2% Solution by Matthew Miller (1/07)

- The World is Flat by Thomas Friedman (1/07)

- The Harried Leisure Class by Staffan Linder (2/07)

- The Age of Abundance by Brink Lindsey (12/07)

- Utilitarianism by John Stuart Mill (12/07)

- Super Crunchers by Ian Ayres (4/08)

- Principles of Macroeconomics by N. Gregory Mankiw (4/09)

- Macroeconomics by Paul Krugman and Robin Wells (11/09)

- In Fed We Trust by David Wessel (1/10)

- The White Man’s Burden by William Easterly (2/10)

- Sonic Boom: Globalization at Mach Speed by Gregg Easterbrook (6/10)

- The Quants by Scott Patterson (6/10)

- A Beautiful Mind by Sylvia Nasar (2/10)

- The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves by Matt Ridley (7/10)

- The Nature of Technology by W. Brian Arthur (8/10)

- The Philosophical Breakfast Club by Laura J. Snyder (4/11)

- Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman (1/12)

- Grand Pursuit: The Story of Economic Genius by Sylvia Nasar (2/12)

- The Road to Serfdom by Friedrich Hayek (4/12)

- Free to Choose by Milton Friedman (5/12)

- A Theory of Justice by John Rawls (7/12)

Outside of what I read for classes (such as

and the 1977 or so edition of Paul Samuelson’s textbook) I can only remember a few economics books I read before I started my book list. Three good ones are

- Social Limits to Growth by Fred Hirsch

- Exit, Voice and Loyalty by Albert O. Hirschman

- Hard Heads, Soft Hearts by Alan Blinder

On your second question, about the Great Depression, I agree with Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz’s view (in a book I’m afraid I haven’t read: A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960) that the depth and length of the Great Depression resulted from bad monetary policy. In my view, the only reason things have been any better in the last few years is because of better monetary policy–in important measure because of Ben Bernanke, but more broadly because the economics profession has learned from its past mistakes. (Paul Krugman’s New York Times column yesterday, “Hating on Ben Bernanke,” is right to criticize the “liquidationist” view. Though one can debate whether it should have gone even further, this past week the Fed moved a long way in the right direction and deserves to be applauded. The views that Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan are expressing about monetary policy are potentially disastrous if they really mean them, and extremely unhealthy even if those expressed views are simply a matter of being willing to say anything to win an election.)

As for FDR, based on economics seminars I have attended, my view is that as a technical economic policy matter (and leaving aside war-related decisions as a separate category) the details of what FDR did in economic policy were a mess, and mostly made things worse during the 1930’s. (The long-run virtues and vices of FDR’s policies that have lasted to the present are still at the center of our political debate.) However,despite how unimpressive FDR’s policies were from a technical point of view,FDR’s success in maintaining a modicum of confidence and so staving off political pressure for a bigger turn toward socialism was a huge contribution. And FDR’s principle of “bold, persistent, experimentation” is wonderful. (I was glad to hear Barack Obama echo those words in his acceptance speech.) I have used this principle of “bold, persistent, experimentation” as a major part of my argument in several posts:

Ezra Klein on the Fed's September 13, 2012 Action →

Ezra gives a great summary of what the Fed did and why it matters.

The Deep Magic of Money and the Deeper Magic of the Supply Side

Introduction

I will assume that you have either read The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, seen the movie, or don’t intend to do either. So I won’t worry about spoiling the story for you. C.S. Lewis’s fantasy is set in the world of Narnia. WikiNarnia explains the laws of nature in Narnia that drive the plot of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe:

The Deep Magic was a set of laws placed into Narnia by the Emperor-beyond-the-Sea at the time of its creation. It was written on the Stone Table, the firestones on the Secret Hill and the sceptre of the Emperor-beyond-the-Sea.

This law stated that the White Witch Jadis was entitled to kill every traitor. If someone denied her this right then all of Narnia would be overturned and perish in fire and water.

Unknown to Jadis, a deeper magic from before the start of Time existed which said that if a willing victim who had comitted no treachery was killed in a traitor’s stead, the Stone Table would crack and Death would start working backwards.

Like the Deep Magic and the Deeper Magic in Narnia, in macroeconomics, money is the Deep Magic and the supply side is the Deeper Magic. In the short run, money rules the roost. In the long run, pretty much, only the supply side matters. In this post, I want to trace out what happens when a strong monetary stimulus is used to increase output and reduce unemployment. In the short run, output will go up, but in the long run, output will return to what it was.

The Deep Magic of Money

Let me start by explaining why money is the Deep Magic of macroeconomics. There are many people in the world today who think it is hard making output go up, and that we need to resort to massive deficit spending by the government spending to stimulate the economy or from tax cuts meant to stimulate the economy. But as I explained in an earlier post, Balance Sheet Monetary Policy: A Primer, there are few limits to the power of money to make output go up in the short run.

Money as a Hot Potato when the Short-Term Safe Interest Rate is Above Zero. When short-term safe interest rates such as the Treasury bill rate or the federal funds rate at which banks lend to each other overnight are positive, almost all economists agree that money is very powerful. Suppose the Federal Reserve (“the Fed”) or some other central bank prints money to buy assets. In this context, when I say “money” I mean currency (in the U.S., green pieces of paper with pictures of dead presidents on them) or the electronic equivalent of currency–what economists sometimes call “high-powered money.” (When the Fed creates the electronic equivalent of currency, it isn’t physically “printing” money but it might as well be.) The Fed requires banks to hold a certain amount of high-powered money in reserve for every dollar of deposits they hold. Any high-powered money that a bank holds beyond that is not needed to meet the reserve requirement and is usually not a good deal because it earns an interest rate of zero (unless the Fed decides to pay more than that for the electronic equivalent of currency held in an account with the Fed). So inside the banking system, reserves beyond those that are required–called “excess reserves”–are usually a hot potato. Also, outside the banking system, at an interest rate of zero, high-powered money is normally a “hot potato” that households and firms other than banks try to spend relatively quickly, since every minute they hold high-powered money they are losing out on higher interest rates they could earn on other assets, such as Treasury bills. I say “relatively” quickly because there is some convenience to currency. So if the Fed prints high-powered money to buy assets, that hot potato money stimulates spending until until people and firms wind up with enough deposits in bank accounts that most of the high-powered money is used up meeting banks’ requirements to hold reserves against deposits, while the rest is in people’s pockets or the equivalent for convenience.

What Happens at the Zero Lower Bound on the Nominal Interest Rate. Many things change when short-term, safe interest rates such as the federal funds rate or the Treasury bill rate get very low, near zero. Then high-powered money is no longer a hot potato, either inside or outside the banking system. Banks and firms and households become willing to keep large piles of high-powered money–piles doing nothing (something even many non-economists have remarked upon lately). In the U.S. extremely low interest rates are a relatively new thing, but Japan has had extremely low interest rates for a long time; in Japan, it is not unusual for people to have thick wads of 10,000-yen notes (worth about $100 each) in their wallets. There are economists who believe that when short-term safe interest rates are essentially zero so that high-powered money is no longer a hot potato that money has lost its magic. Not so. Printing money to buy assets has two effects: one from the printing of the money, the other from the buying of the assets. That effect can be important, depending on what asset the Fed is buying.

Normally, the Fed likes to buy Treasury bills when it prints money. But buying Treasury bills really does lose its magic after a while. Interest rates on Treasury bills falling to zero is equivalent to people being willing to pay a full $10,000 for the promise of receiving $10,000 three months later. (You can see that the interest rate is then zero, since you don’t get any more dollars back than what you put in. If you paid less than $10,000 at first, then you would be getting more dollars back at the end than what you put in, so you would be earning some interest.) No one is willing to pay much more than $10,000 for the promise of $10,000 in three months, since other than the cost of storage, one can always get $10,000 in three months just by finding a very good hiding place for $10,000 in currency. So when the interest rate on Treasury bills has fallen to zero, it is not only impossible to push that interest rate significantly below zero, in what turns out to be the same thing, it is impossible to push the price of a Treasury bill that pays $10,000 in three months significantly above $10,000.

Fortunately, there are many other assets in the world to buy other than Treasury bills. Unfortunately, the Fed only has the legal authority to buy a few types of assets. It can buy long-term U.S. Treasury bonds. It can buy mortgage-backed assets from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac–which are companies that were created by the government to make it easier for people to buy houses. (They used to be somewhat separate from the government, despite being created by the government, but the government had to fully take them over in the recent financial crisis.) The Fed can buy bonds issued by cities and states. It can also buy bonds issued by other countries (as long as the bonds are reasonably safe), but usually doesn’t, since other countries would have strong opinions about that. A key thing the Fed does not feel it is allowed to do is to buy packages of corporate stocks and bonds. Still, with the menu of assets the Fed clearly is allowed to buy, it can have a big effect on the economy, even when short-term, safe interest rates are basically zero.

If the Fed buys packages of mortgages, it pushes up the price of those mortgage-backed assets. When the price of mortgage-backed assets is high, financial firms become more eager to lend money for mortgages, even though they remain somewhat cautious because they (or others who serve as cautionary tales) were burned by mortgages that went sour as part of the financial crisis. If financial firms become eager to lend against houses, more people will be able to refinance and spend the money they get or that they save from lower monthly house payments, and some may even build a new house.

If the Fed buys long-term Treasury bonds, that pushes up their price, making them more expensive. Some firms and households who had intended by buy Treasury bonds will now find them too pricey as a way to get a fixed payoff in the future. With Treasury bonds too pricey, they will look for ways to get payoffs in the future that are not so pricey now. They may hold onto their hats and buy corporate bonds or even corporate stock, despite the risk. That makes it easier for companies to raise money by selling additional stocks and bonds. Up to a point it also pushes up the price of stocks and bonds, so that people looking at their brokerage accounts or their retirement accounts feel richer and may spend more. If you don’t believe me, just watch how joyous the stock market seems every time the Fed surprises people by announcing that it will buy more long-term Treasury bonds than people expected–or how disappointed the stock market seems every time the Fed surprises people by announcing that it won’t buy as many long-term Treasury bonds as people had expected.

The Cost of the Limited Range of Assets the Fed is Allowed to Buy. It is true that at some point the legal limits on what the Fed is allowed to buy will put a brake on how much the Fed can stimulate the economy. But that does not deny the power of money to raise the price of assets and stimulate the economy, it only means that when we don’t allow newly created money to be used to buy a wide range of assets, then money is hobbled. Aside from the effect limits on what the Fed can buy have on the ability of money to stimulate the economy, those limits also affect the cost of what the Fed does. If the Fed is only allowed to buy a narrow range of assets, it will have to push the price of each of those assets up a lot to get the desired effect, and then when it sells them again to avoid the economy overheating, it may lose money from the roundtrip of buying high (when it pushed the price up by buying) and selling low (when it later pulls the price down by selling). This is a bigger problem the lower the interest rate on a given type of asset is to begin with. It is also a bigger problem the longer-term an asset is. So risky assets that have higher interest rates to begin with–and perhaps, especially, risky short-term assets–are better in that regard.

Summarizing the Deep Magic of Money. The bottom line is that in the short run, money has deep magic that can stimulate the economy as much as desired. Right now, the power of money is as about as circumscribed as it ever is, and yet it still has its magic. And yet, I claim, as almost all other economists claim, that in the long run, the supply side will win out. Not only will the supply side win out in the long run, but in the long run, money has virtually no power to affect anything important–unless continual, rampant printing of money drives the economy into the disaster of hyperinflation, or a serious shortage of money causes prices to fall in a long-lasting bout of deflation. (The fact that, short of hyperinflation or deflation, money has virtually no power to affect anything important in the long run is called monetary superneutrality.) How can money have so much power in the short run and so little in the long run?

The Deeper Magic of the Supply Side

The answer to how money can have so much power in the short run and so little in the long run is that the supply side will bend in many ways in the short run, but will always bounce back.

Price Above Marginal Cost Makes Output Demand-Determined in the Short Run. To begin with, the most basic way in which the supply side is accomodating in the short run is that if a firm has–for some period of time–fixed a price above the cost to produce an extra unit of its good or service (the marginal cost), then it is eager to sell its good or service to any extra customer who walks in the door. And firms will, in general, set their prices at least a little above what it normally costs to produce an extra unit as long as they can do so without losing all of their existing customers. Here is why. Thinking in long-run terms, if the firm sets its price equal to marginal cost, then it doesn’t earn anything from the last few customers. So losing that customer by raising the price a little is no harm. And raising the price a little means that all of the customers who don’t bolt will now be paying more–more that will go into the firm’s pocket. Raising the price too high puts that extra pocket money in jeopardy, so the firm won’t raise prices too high, but it will raise the price at least some above marginal cost as long as it doesn’t lose all of its customers by doing so. To summarize, if firms do fix prices for some length of time as opposed to changing them all the time, they are likely to set those prices above what it normally costs to produce an extra unit of the good or service they sell. And if price is above marginal cost, then given a temporarily fixed price, the amount by which price is above marginal cost is what the firm gets on net when an extra customer walks in the door. For example, produce a widget for a marginal cost of $6, sell it for $10, and take home $4 as extra profits.

So firms who won’t lose every last customer by raising their price will set price above marginal cost, and then will typically be eager to sell to an extra customer during the period when their price is fixed. I say “typically” because if enough new customers walked in the door, then marginal cost might increase enough above normal to exceed the fixed price. Then the firm would lose money by selling further units, and it will make up an excuse to tell customers about why it won’t sell more. The usual excuse is “we have run out”–which is a polite way of saying that they could do more, for a high enough price, but won’t for the price they have actually set. But since the firm will set price some distance above marginal cost to begin with, there is some buffer in which marginal cost can increase without going above the price. And anywhere in that buffer zone, the firm will still be eager to serve additional customers.

How Extra Output is Produced in the Short Run. How does the firm actually produce extra units in the short run? Here it is more interesting to broaden the scope to the whole economy. (Much of what follows is drawn from a paper I teamed up with Susanto Basu and John Fernald to write: “Are Technology Improvements Contractionary?”–a paper that has to consider what happens as a result of changes in demand before it can begin to address what happens with a supply-side change in technology.) When the amount customers are spending increases, so that firms need to produce more to serve that extra quantity demanded, the firms may, at the end of the day hire additional employees. But that is usually a last resort. There are many other ways to increase output short of hiring a new employee. Here are three avenues to increase production even before hiring new workers:

- ask existing employees to stay longer and work more hours in a week and take fewer vacations;

- ask existing employees to work harder while they are at work–to be more focused while at their stations or their desks, and to spend less time away from their work at the water cooler;

- delay maintenance of the factory, training, and other activities that can help the firm’s productivity in the long run, but don’t help produce the output the customer needs today.

The Workweek of Capital. One thing that doesn’t have time to contribute much to output when demand goes up is new machines and factories. It is simply hard to add new machines and factories fast enough to contribute that big a percentage of the increase in output. But people working longer hours with the same number of machines and factories don’t necessarily have to crowd around the limited number of machines and workspaces, since those machines and workspaces were often unused after hours anyway. So when the workers work longer, so do their machines and workspaces. Even when new workers are added, they can often be added in a new shift at a time when the machines and workspaces had been unused. So the fact that it is hard to quickly add extra factories and machines is not as big a limitation to output in the short run as one might think. Of course using machines and workspaces around the clock has costs. Extra wear and tear is one cost, but probably a bigger cost is having to pay people extra to be willing to work at the inconvenient hours of a second or third shift. (Note that paying an inexperienced worker working at night the same as a more experienced worker during the day is also paying extra beyond what the inexperienced worker would be worth for production if he or she were working during the day.)

Reallocation of Labor. At the economy-wide level another contribution to higher GDP in a boom is that in a boom the amount of work done tends to increase most in those sectors of the economy where a 1% increase in inputs leads to considerably more than a 1% increase in output–that is, in sectors such as the automobile sector where there are strong economies of scale (also called increasing returns to scale). These tend to also be sectors in which the price of output, and therefore the marginal value of output, is the furthest above the marginal cost of output. So when more work is done in those sectors, it adds a lot of valuable output that adds a lot to GDP–a lot more than if extra work by that same person were done in another sector where the price (and therefore the marginal value) of output is not as far above marginal cost.

Okun’s Law. When firms are finally driven to hiring additional workers, this still doesn’t reduce the number of “unemployed” workers by an equal amount, for the simple reason that, when firms are hiring, more people decide it is a good time to look for a job, and go from being “out of the labor force” (not looking for work) to “in the labor force and unemployed” (looking for work but haven’t found it yet). So in addition to all the ways that firms can increase output without hiring extra workers, the fact that hiring extra workers causes more worker to look for work also makes it hard to make the unemployment rate go down. So hard, in fact, that the current estimates for what is called “Okun’s Law” (after the economist Arthur Okun) say that it typically takes 2% higher output to make the unemployment rate 1 percentage point lower. (Note that a typical constant-returns to scale production function would say that 2% higher output would require 3% higher labor input. Thus, if 2% higher output came simply from hiring extra workers for a constant returns to scale production function, then the unemployment rate would go down almost 3%. So the details of how firms manage to produce more output matter a lot.)

The Supply Side in the Short Run and in the Long Run. That is the story of the short run. Extra money increases the amount that firms and households want to spend. Firms accommodate that extra desire to spend because price is above marginal cost. They actually produce the extra output by a combination of hiring extra workers and asking existing workers to work longer and harder, in a way that often takes advantage of economies of scale. Firms also may focus their productive efforts more on immediately salable output. They deal with a relatively fixed number of workspaces and machines by keeping the factory or office in operation more hours of the week.

The thing to notice is that both the ways in which the firms accommodate extra demand and their motivation for doing so rely on things that won’t last forever. Workers may work longer and harder without complaint for a while, but sooner or later they will start to grumble about the long hours and the pace of work, and maybe begin looking for another job. Of course, they may not even have to look for another job, since with a booming economy, a job may come looking for them. So even a boss who is too dense to realize all along the strain he or she is putting workers through, will eventually realize the cost of those extra hours and effort as wages get driven up labor market competition. What is more, the boss will eventually get around to raising the firm’s prices in line with this increased marginal cost as the “shadow wage” of the extra strain on workers goes up (something smart bosses will pay attention to) and ultimately the actual wage goes up (which will catch the attention of even dense bosses).

As prices rise throughout the economy, another force kicks in: workers will realize they are working hard for a paycheck that doesn’t stretch as far anymore, and start to wonder “Is it worth spending so many long, hard, late hours at work?” Even when the workers’ answer is still “On balance, yes,” because the answer is no longer “YES!” they will not jump to the boss’s orders with the same speed anymore, which will make the boss see the workers as less productive, and therefore see a higher marginal cost of output. All of this speeds the increase in prices even more, and speeds the return of hours worked and intensity of work to a normal pace. The temporary bending of the supply side toward greater production will be undone. There are things that permanently affect the supply side, but short of a monetary disaster, money is not one of those things. Short of a monetary disaster, and leaving aside tiny effects, money only matters in the short run. Economists call this monetary superneutrality and say that money only matters in the short run by saying the words the long-run aggregate supply curve is vertical.

Three Codas: Inflation Magic, Sticky vs. Flexible Prices, and Federal Lines of Credit

Is There Any Direct Magic by which Money Causes Inflation? A crucial aspect of the story above is that money only causes a general increase in prices–inflation–by increasing output and leading to all the measures discussed above to produce more output. Some economists think that printing money can cause inflation even if it doesn’t lead to an increase in output. Money has magic, but not that kind of magic.

Let me discuss the two closest things I can think of to money having some direct magic that could raise inflation even without an increase in output.

- First, to some extent, inflation can be a self-fulfilling prophecy. If firms believe that prices will be higher in the future, those who have gotten around to changing prices will set higher prices now. So if firms believed that printing money could cause inflation without increasing output, then to some extent it would. But I see no evidence that many firms believe this. They know how hard it is for them to raise prices in their own industry when demand is low.

- Printing money to buy assets drives up the prices of assets in general, as financial investors look for assets that are still reasonably priced to buy, bringing up their prices as well. Many commodities, such as oil, copper, and even cattle, have an asset-like quality because they can be used either now or later. (And copper–and depending on the use, cattle–can be used both now and later.) When the Fed pushes up the prices of assets, it pushes up what people are willing to pay now for a payout down the road. That pushes up the price of oil, copper, and cattle now. This looks like inflation, but it is not a general increase in prices, but an increase in commodity prices relative to other prices in the economy. When the economy cools down (often, unlike the story above, because the Fed sells assets to mop up money and cool down an overheated economy), all of these increases in commodity prices go in reverse, and the roundtrip effect on the overall price level from the rise and fall of commodity prices along the way is modest.

Sticky Prices vs. Flexible Prices. Some prices are relatively flexible and quick to change, while others are fixed for a relatively long period of time. (I don’t emphasize wages being fixed for often as much as a year at a time, since a smart boss should realize that in a long-term relationship, a high level of strain on workers, which can come on quickly, leads to extra costs even if the actual wage changes only slowly.) Prices are especially flexible and quick to change for the long-lasting commodities I discussed above, and for relatively unprocessed food such as bananas and orange juice. (In relatively unprocessed food, most of the cost is from the ingredients and bringing the food to the customer rather than the processing. And it is hard to differentiate one’s product from the competition’s product, so the price can’t be pushed very far above marginal cost.) Another interesting area where prices are very flexible is in air travel, where ticket prices can change dramatically from one week to the next. By contrast, prices are fixed for relatively long periods of time for most services. (My wife Gail is a massage therapist. I know that massage therapists think long and hard before they raise prices on their clients, and warn their clients long in advance about any price increase. In an even more extreme example, it is not uncommon for psychotherapists to keep their price fixed for a given client during the whole period of treatment, even if it lasts for years.) The prices of manufactured goods are in-between in their degree of flexibility.

When demand is high so that the economy booms, flexible prices move up quickly, while sticky prices move up only slowly. But when the economy cools down, the flexible prices can easily reverse course, while the sticky prices have momentum. (Greg Mankiw and Ricardo Reis explain one mechanism behind this momentum in their paper “Sticky Information Versus Sticky Prices: A Proposal to Replace the New Keynesian Phillips Curve”: firms’ sense of the rate of inflation–often based on old news–feeds into their price-setting. In this account, inflation feeds on past inflation that affects that sense of what the rate of inflation is.) So, perhaps counterintuitively, it is inflation in sticky prices that is the most worrisome. The Fed is right to focus its worries about inflation on what is happening to the sticky prices. In the news, this is described as focusing on “core inflation”–the overall rate of price increases for goods other than oil and food.

The existence of a mix of flexible and sticky prices in the economy is important for macroeconomic models, since it means that higher aggregate demand will have some immediate effect on prices (because of the flexible prices), but the effect on the overall price level will still be limited (because of the sticky prices). Economists often describe this as the “short-run aggregate supply curve” sloping upward–as opposed to being vertical, as it would be if all prices were flexible, or horizontal, as it would be if all prices were sticky. The existence of a mix of flexible and sticky prices is also important because it means that this “short-run aggregate supply curve” can shift when flexible prices change for reasons other than the level of aggregate demand. (Unfortunately, the most obvious reason the “short-run aggregate supply curve” might shift is because of a war in the Middle East that raises the price of oil in a way that is not do to the level of aggregate demand.)

Federal Lines of Credit. I have focused on monetary policy in this post, arguing that traditional fiscal stimulus–government spending or tax cuts meant to stimulate the economy in the short run–is inferior because it adds so much to the national debt. But there is one type of fiscal policy that adds relatively little to the national debt, as I discuss in my post “Getting the Biggest Bang for the Buck in Fiscal Policy.” The “Federal Lines of Credit” I propose in that post are a type of fiscal policy that is similar in some ways to monetary policy, since Federal Lines of Credit involve the government making loans to households. Federal Lines of Credit, like money, have deep magic, but in the long run their effects on output will also be countered by the deeper magic of the supply side.

Miles's Teaching Tumblog →

There are some posts I am using for my Principles of Macroeconomics class I think most readers of this blog will not be interested in, but that I want to make available to anyone who is interested. I am going to put them on a secondary Tumbler blog. Here is the link again. And here is the link spelled out:

http://profmileskimball.tumblr.com

I will also put a link on my sidebar, so you can always access it.

The first post on my Teaching Tumblog is up. I typically won’t announce each post on my Teaching Tumblog. You will have to go look to see what is there.

Why I am a Macroeconomist: Increasing Returns and Unemployment

During my first year in Harvard’s Economic Ph.D. program (1983-1984), I thought to myself I could never be a macroeconomist, because I couldn’t figure out where the equations came from in the macro papers we were studying. In my second year, I focused on microeconomic theory, with Andreu Mas-Colell as my main role model. Then, during the first few months of calendar 1985, I stumbled across Martin Weitzman’s paper “Increasing Returns and the Foundations of Unemployment Theory” in the Economics Department library. Marty’s paper made me decide to be a macroeconomist. (I took the macroeconomics field courses and began working on writing some macroeconomics papers the following year, my third year–the year Greg Mankiw joined the Harvard faculty–and went on the job market in my fourth year.) I want to give you some of the highlights from “Increasing Returns and the Foundations of Unemployment Theory”, not only so you can see what affected me so strongly, but also because it includes ideas that every serious economist should have in his or her mental arsenal. Marty’s paper is a “big-think” paper. It has a lot to say, even after all of the equations were stripped out of it.

There is one important piece of background before turning to Marty’s paper: Say’s Law. In Say’s own words, organized by the wikipedia article on Say’s Law:

In Say’s language, “products are paid for with products” (1803: p. 153) or “a glut can take place only when there are too many means of production applied to one kind of product and not enough to another” (1803: p. 178-9). Explaining his point at length, he wrote that:

It is worthwhile to remark that a product is no sooner created than it, from that instant, affords a market for other products to the full extent of its own value. When the producer has put the finishing hand to his product, he is most anxious to sell it immediately, lest its value should diminish in his hands. Nor is he less anxious to dispose of the money he may get for it; for the value of money is also perishable. But the only way of getting rid of money is in the purchase of some product or other. Thus the mere circumstance of creation of one product immediately opens a vent for other products. (J. B. Say, 1803: pp.138–9)

Say’s Law is sometimes expressed as “Supply creates its own demand.” Say’s law seems to deny the possibility of Keynesian unemployment–unemployed workers who are identical in their productivity to workers who have jobs, and are willing to work for the same wages, but cannot find a job in a reasonable amount of time. The argument of Say’s law needs to be countered in some way in order to argue for the existence of Keynesian unemployment. Marty paints of picture of Keynesian unemployment in this way:

In a modern economy, many different goods are produced and consumed. Each firm is a specialist in production, while its workers are generalists in consumption. Workers receive a wage from the firm they work for, but they spend it almost entirely on the products of other firms. To obtain a wage, the unemployed worker must first succeed in being hired. However, when demand is depressed because of unemployment, each firm sees no indication it can profitably market the increased output of an extra worker. The inability of the unemployed to communicate effective demand results in a vicious circle of self-sustaining involuntary unemployment. There is an atmosphere of frustration because the problem is beyond the power of any single firm to correct, yet would go away if only all firms would simultaneously expand output. It is difficult to describe this kind of ‘prisoner’s dilemma’ unemployment rigorously, much less explain it, in an artificially aggregated economy that produces essentially one good.

Marty mentions one economic fact that has big implications even outside of business cycle theory. A remarkable fact about the political economy of trade is that trade policy often favors the interests of producers over the interests of consumers. Why are producer lobbies more powerful than consumer lobbies? The key underlying fact is that “Each firm is a specialist in production, while its workers are generalists in consumption.” So particular firms and the workers of those firms care a huge amount about trade policy for the good that they make, while the many consumers who would each benefit a little from a lower price with free imports are not focused on the issue of that particular good, since it is only a small share of their overall consumption. The exceptions, where consumer interests take the front seat in policy making, are typically where the good in question is a very large share of the consumption bundle (such as wheat or rice in poor countries) or where trade policy for many different goods has been combined into an overall trade package that could make a noticeable difference for an individual consumer. Other political actions that depart from the free market often follow a similar principle–either favoring a producer or favoring households interests in relation to a good that is a large share of the household’s budget, such as rent, or a very salient good such as gasoline, which seems to consumers as if it is even more important for their budgets than it really is.

After painting the picture of the world that he wants to provide a foundation for, Marty dives into his main argument–that increasing returns is essential if one wants to explain unemployment.

In this paper I want to argue that the ultimate source of unemployment equilibrium is increasing returns. When compared at the same level of aggregation, the fundamental differences between classical and unemployment versions of general equilibrium theory trace back to the issue of returns to scale.

More formally, I hope to show that the very logic of strict constant returns to scale (plus symmetric information) must imply full employment, whereas unemployment can occur quite naturally with increasing returns

He argues that much the same issues would arise from increasing returns to scale from a wide variety of difference causes:

The reasons for increasing returns are anything that makes average productivity increase with scale - such as physical economies of area or volume, the internalisation of positive externalities, economising on information or transactions, use of inanimate power, division of labour, specialisation of roles or functions, standardisation of parts, the law of large numbers, access to financial capital, etc., etc.

Marty lays out a sequence of three models. Here are the first two models or “stages”:

III. STAGE I: SELF SUFFICIENCY

Suppose each labourer can produce α units of any commodity. In such a world the economic problem has a trivial Robinson Crusoe solution. A person of attribute type i simply produces and consumes α units of commodity i.

IV. STAGE II: SMALL SCALE SPECIALISATION

Now suppose a person of type (i,j) prefers to consume i but has a comparative advantage in producing j.

In such an economy there can be no true unemployment because there are no true firms. If anyone is declared 'unemployed’ by a firm, he can just announce his own miniature firm, hire himself, and sell the product directly on a perfectly competitive market.

In the context of the “Stage II” model, Marty points to increasing returns to scale not only as the explanation for unemployment, but also as what makes plants discrete entities (in this paper he does not distinguish between plants and firms):

In a constant returns economy the firm is an artificial entity. It does not matter how the boundary of a firm is drawn or even if it is drawn at all. There is no operational distinction between the size of a firm and the number of firms.

Also, increasing returns to scale is the reason it is typical for a firm, defined in important measure by its capital, to hire workers, rather than the other way around. With constant returns to scale, workers could easily hire capital and there would be less unemployment:

When unemployed factor units are all going about their business spontaneously employing themselves or being employed, the economy will automatically break out of unemployment.

One reason increasing returns to scale is so powerful in its effects is that it is closely linked to imperfect competition–as constant returns to scale is closely linked to perfect competition.

The seemingly institution-free or purely technological question of the extent of increasing returns is a loaded issue precisely because the existence of pure competition is at stake.

To emphasise a basic truth dramatically, let the case be overstated here. Increasing returns, understood in its broadest sense, is the natural enemy of pure competition and the primary cause of imperfect competition. (Leave aside such rarities as the monopoly ownership of a particular factor.)

After laying out a particular macroeconomic model with increasing returns to scale, Marty directly addresses Say’s law, writing this:

Behind a mathematical veneer, the arguments used in the new classical macroeconomics to discredit steady state involuntary unemployment are implicitly based on some version or other of Say’s Law. It is true that under strict constant returns to scale and perfect competition, Say’s Law will operate to ensure that involuntary unemployment is automatically eliminated by the self interested actions of economic agents. Each existing or potential firm knows that irrespective of what the other firms do it cannot glut its own market by unilaterally expanding production, hence a balanced expansion of the entire underemployed econorny in fact takes place. But increasing returns prevents supply from creating its own demand because the unemployed workers are essentially blocked from producing. Either the existing firms will not hire them given the current state of demand, or, even if a group of unemployed workers can be coalesced effectively into a discrete lump of new supply, it will spoil the market price before ever giving Say’s Law a chance to start operating. When each firm is afraid of glutting its own local market by unilaterally increasing output, the economy can get trapped in a low level equilibrium simply because there is insufficient pressure for the balanced simultaneous expansion of all markets. Correcting this 'externality’, if that is how it is viewed, requires nothing less than economy-wide coordination or stimulation. The usual invisible hand stories about the corrective powers of arbitrage do not apply to effective demand failures of the type considered here.

To this day–more than 27 years later–I stand convinced that increasing returns to scale are essential to understanding macroeconomics in the real world. Much of what we see around us stems from the inability of half a factory, staffed with half as many workers, to produce half the output. Despite the difficulty of explaining Marty’s logic for why increasing returns to scale matters and what its detailed consequences are, I believe Intermediate Macroeconomics textbooks–and even Principles of Macroeconomics textbooks–need to try. Anyone who learns much macroeconomics at all should not be denied a chance to hear some of Marty’s logic.

Rodney Stark on a Major Academic Pitfall

Rodney Stark writes of an unfortunate side-effect of academic incentives in his book Discovering God: The Origins of the Great Religions and the Evolution of Belief. Although his specific context is New Testament scholarship, the incentives he points to operate in all areas of academia:

In order to enjoy academic success one must innovate; novelty at almost any cost is the key to a big reputation. This rule holds across the board and has often inflicted remarkably foolish new approaches on many fields. (pp. 294-295.)

In my experience, the only truly effective defenses against the danger Rodney points to are to have research disciplined by either abundant data or by rigorous logic like that used in mathematics.

My Proudest Moment as a Student in Ph.D. Classes

Is it a watermelon or is it an ellipsoid?

Ellipsoids, which are more or less a watermelon shape, are important in econometrics. In my Ph.D. Econometrics class at Harvard, Dale Jorgenson explained the effect of linear constraints by saying that slicing a plane through an ellipsoid would be like slicing a watermelon. Slices of a 3-dimensional ellipse–a watermelon–are in the shape of a 2-dimensional ellipse–a watermelon slice. Dale’s analogy of watermelons and watermelon slices inspired me to exclaim that slicing a 4-dimensional ellipsoid with a hyperplane would get you a whole watermelon!

Another Reminiscence from My Ec 10 Teacher, Mary O'Keeffe

In 1977-78, I taught my first very class as a section-leader for Ec 10 (intro economics) at Harvard. There were 30 sections of Ec 10, but I taught one of the two “math sections” of that class, designed for students taking the minimum co-requisite of multivariable calculus or higher levels classes. (The other math section was taught by Larry Summers. Random chance divided which students each of us got since virtually all sections of the class met at noon M-W-F.)

Two very memorable students stand out in my head from that first class. One is now a very famous journalist, a writer and TV media pundit/personality, who shall remain nameless, because back then he was comping for the Crimson (i.e. Harvard-speak for freshmen competing to prove themselves as reporters for the student newspaper so they would be accepted as a member of their permanent staff)–this meant he spent many late nights in the Crimson offices. As a result, he was primarily memorable for frequently falling asleep in the back of my classroom, despite the noon meeting hour of the class. One day I had requested a Harvard videographer to tape my class (so I could improve my teaching) and I remember greeting this student at the door jokingly asking that–at least today–he attempt to stay awake in the class–so he would not be captured for posterity sleeping through the class. What I did not realize until seconds later was that it was “Parents Day,” a time when parents could visit and attend classes with their Harvard freshmen, and his horror-stricken parents were right behind him. Anyway, aforesaid student later made the Crimson staff, graduated, and went on to distinction in law school and journalism.

The other student who stands out in my head was the polar opposite of the aforementioned nameless student. He always arrived very bright-eyed and eager to absorb all he could of what little I had to offer at the time. He sat in the front row of the classroom, right under my nose, wearing a brightly colored jacket (my memory says it was royal blue with his name in vivid gold embroidery: Miles Kimball, but Christopher Chabris has taught me enough about the tricks that memory plays that I could be wrong. Maybe it was a red jacket with white embroidery? Anyway, it was distinctive and I can still see it in my mind’s eye today, as well as his sparkling engaged eyes.)

I was Miles’ teacher then, but reading this last post on his blog makes me wish that I myself had had the good fortune to have a professor like him early in my own development–one who blended math so beautifully with economics as well as music. I teach public finance, not macroeconomics, but logarithms are important everywhere in economics, yet the word all too frequently makes the eyes glaze over (especially if one has been up late comping for the Crimson–or partying–or working on assignments for other classes.)

This post [“The Logarithmic Harmony of Percent Changes and Growth Rates”] from Miles’ blog is so awesome that I am tagging it to share with my students in Eco 339 Public Finance as well as my mathy students in Albany Area Math Circle and Math Prize for Girls.

[Note: Mary’s memory is good: my brother Chris had that royal blue running jacket made in Korea, where he served as a Mormon missionary. You may remember Chris from the post “Big Brother Speaks: Christian Kimball on Mitt Romney,”]

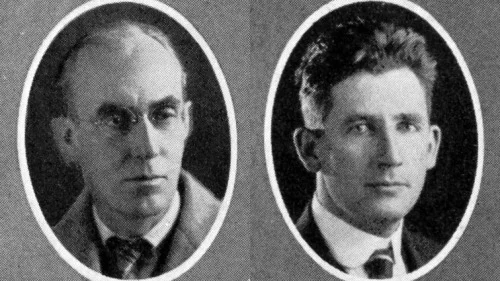

The Shape of Production: Charles Cobb's and Paul Douglas's Boon to Economics

Paul Douglas, Economist and Senator from Illinois Paul Douglas was not only an economist, but one of the most admirable politicians I have ever read about. See what you think: here is the wikipedia article on Paul. I would be interested in whether there are any skeletons in his closet that this article is silent on. If the Devil’s Advocate’s case is weak, he may qualify as a Supply-Side Liberal saint. (He was divorced, so a Devil’s Advocate might have something to work with. See my discussion of saints and heroes in “Adam Smith as Patron Saint of Supply-Side Liberalism?”) Paul was one of Barack’s predecessors as senator of Illinois, serving from 1949-1967, but chose not to run for president when he was given the chance.

In 1927, before he dove fully into politics, Paul teamed up with mathematician and economist Charles Cobb to develop and apply what has come to be called the “Cobb-Douglas” production function. (The wikipedia article on Charles Cobb is just a stub, so I don’t know much about him.) Here is the equation:

A very famous economist, Knut Wicksell, had used this equation before, but it was the work of Charles Cobb and Paul Douglas that gave this equation currency in economics. Because of their work, Paul Samuelson–a towering giant of economics–and his fellow Nobel laureate Robert Solow, picked up on this functional form. (Paul Samuelson did more than any other single person to transform economics from a subject with many words and a little mathematics, to a subject dominated by mathematics.)

In the equation, the letter A represents the level of technology, which will be a constant in this post. (If you want to think more about technology, you might be interested in my post “Two Types of Knowledge: Human Capital and Information.”) The Greek letter alpha, which looks like a fish (α), represents a number between 0 and 1 that shows how important physical capital, K–such as machines, factories or office buildings–is in producing output, Y. The complementary expression (1-α) represents a number between 0 and 1 that shows how important labor, L, is in producing output, Y. For now, think of α as being 1/3 and (1-α) as being 2/3:

- α= 1/3;

- (1-α) = 2/3.

As long at the production function has constant returns to scale so that doubling both capital and labor would double output as here, the formal names for α and 1-α are

- α = the elasticity of output with respect to capital

- 1-α = the elasticity of output with respect to labor.

What Makes Cobb-Douglas Functions So Great. The Cobb-Douglas function has a key property that both makes it convenient in theoretical models and makes it relatively easy to judge when it is the right functional form to model real-world situations: the constant-share property. My goal in this post is to explain what the constant-share property is and why it holds, using the logarithmic percent change tools I laid out in my post “The Logarithmic Harmony of Percent Changes and Growth Rates.” If any of the math below seems hard or unclear, please try reading that post and then coming back to this one.

The Logarithmic Form of the Cobb-Douglas Equation. By taking the natural logarithm of both sides of the defining equation for the Cobb-Douglas production function above, that equation can be rewritten this way:

log(Y) = log(A) + α log(K) + (1-α) log(L)

This is an equation that holds all the time, as long as the production engineers and other organizers of production are doing a good job. If two things are equal all the time, then changes in those two things must also be equal. Thus,

Δ log(Y) = Δ log(A) + Δ {α log(K)} + Δ {(1-α) log(L)}.

Remember that, for now, α= 1/3. The change in 1/3 of log(K) is 1/3 of the change in log(K). Also, the change in 2/3 of log(L) is 2/3 of the change in log(L). And quite generally, constants can be moved in front of the change operator Δ in equations. (Δ is also called a “difference operator” or “first difference operator.”) So

Δ log(Y) = Δ log(A) + α Δ log(K) + (1-α) Δ log(L).

As defined in “The Logarithmic Harmony of Percent Changes and Growth Rates,”the change in the logarithm of X is the Platonic percent change in X. In that statement X can be anything, including Y, A, K or L. So as long as we interpret %Δ in the Platonic way,

%ΔY = %ΔA + α %ΔK + (1-α) %ΔL

is an exact equation, given the assumption of a Cobb-Douglas production function.

Percent Changes of Sums: An Approximation. Now let me turn to an approximate equation, but one that is very close to being exact for small changes. Economists call small changes marginal changes, so what I am about to do is marginal analysis. (By the way, the name of Tyler Cowen and Alex Tabarrok’s popular blog Marginal Revolutionis a pun on the “Marginal Revolution” in economics in the 19th century when many economists realized that focusing on small changes added a great deal of analytic power.)

For small changes,

%Δ (X+Z) ≈ [X/(X+Z)] %ΔX + [Z/(X+Z)] %ΔZ,

where X and Z can be anything. (Those of you who know differential calculus can see where this approximation comes from by showing that d log(X+Z) = [X/(X+Z)] d log(X) + [Z/(X+Z)] d log(Z)], which says that the approximation gets extremely good when the changes are very small. But as long as you are willing to trust me on this approximate equation for percent changes of sums, you won’t need any calculus to understand the rest of this post.)

The ratios X/(X+Z) and Z/(X+Z) are very important. Think of X/(X+Z) as the fraction of X+Z accounted for by X; and think of Z/(X+Z) as the fraction of X+Z accounted for by Z. Economists use this terminology:

- X/(X+Z) is the “share of X in X+Z.”

- Z/(X+Z) is the “share of Z in X+Z."

By the way they are defined, the shares of X and Z in X+Z add up to 1.

The main reason the rule for the percent changes of sums is only an approximation is that the shares of X and Z don’t stay fixed at their starting values. The shares of X and Z change as X and Z change. Indeed, if one changed X and Z gradually (avoiding any point where X+Z=0), the approximate rule for the percent change of sums would have to hold exactly for some pair of values of the shares of X and Z passed through along the way.

The Cost Shares of Capital and Labor. Remember that in the approximate rule for the Platonic percent change of sums, X and Z can be anything. In thinking about the production decision of firms, it is especially useful to think of X as the amount of money that a firm spends on capital and Z as the amount of money the firm spends on labor. If we write R for the price of capital (the "Rental price” of capital) and W for the price of labor (the “Wage” of labor), this yields

- X = RK

- Z = WL.

For the issues at hand, it doesn’t matter whether the amount R that it costs to rent a machine or an office and the amount W it costs to hire an hour of labor is real (adjusted for inflation) or nominal. It does matter, though, that nothing the firm can do will change R or W. The kind of analysis done here would work if what the firm does affects R and W, but the results, including the constant-share property, would be altered. I am going to analyze the case when the firm cannot affect R and W–that is, I am assuming the firm faces competitive markets for physical capital and labor. Substituting RK in for X and WL in for Z, the approximate equation for percent changes of sums becomes

%Δ (RK+WL) ≈ [RK/(RK+WL)] %Δ(RK) + [WL/(RK+WL)] %Δ(WL)

Economically, this approximate equation is important because RK+WL is the total cost of production. RK+WL is the total cost because the only costs are total rentals for capital RK and total wages WL. In this approximate equation

- s_K = share_K = RK/(RK+WL) is the cost share of capital (the share of the cost of capital rentals in total cost.)

- s_L = share_L = WL/(RK+WL) is the cost share of labor (the share of the cost of the wages of labor in total cost.)

The two shares always add up to 1 (as can be confirmed with a little algebra), so

s_L = 1 - s_K.

Using this notation for the shares, the approximation for the percent change of total costs is

%Δ (RK+WL) ≈ {s_K} %Δ(RK) + {s_L} %Δ(WL).

The Product Rule for Percent Changes. In order to expand the approximation above, I am going to need the rule for percent changes of products. Let me spell out the rule, along with its justification twice, using RK and WL as examples:

%Δ (RK) = Δ log(RK) = Δ {log( R ) + log(K)} = Δ log( R ) + Δ log(K) = %ΔR + %ΔK

%Δ (WL) = Δ log(WL) = Δ {log(W) + log(L)} = Δ log(W) + Δ log(L) = %ΔW + %ΔL

These equations, reflecting the rule for percent changes of products, hold exactly for Platonic percent changes. Aside from the definition of Platonic percent changes as the change in the natural logarithm, what I need to back up these equations is the fact that the change in one thing plus another, say log( R ) + log(K), is equal to the change in one plus the change in the other, so that Δ {log( R ) + log(K)} = Δ log( R ) + Δ log(K). Using the product rule,

%Δ (RK+WL) ≈ {s_K} (%ΔR + %ΔK) + {s_L} (%ΔW+ %ΔL).

Cost-Minimization. Let’s focus now on the firm’s aim of producing a given amount of output Y at least cost. We can think of the firm exploring different values of capital K and labor L that produce the same amount of output Y. An important reason to focus on changes that keep the amount of output the same is that it sidesteps the whole question of how much control the firm has over how much it sells, and what the costs and benefits are of changing the amount it sells. Therefore, focusing on different values of capital and labor that produce the same amount of output yields results that apply to many different possible selling situations (=marketing situations=industrial organization situations=competitive situations) a firm may be in. That is, I am going to rely on the firm facing a simple situation for buying the time of capital and labor, but I am going to try not to make too many assumptions about the details of the firm’s selling, marketing, industrial organization, and competitive situation. (The biggest way I can think of in which a firm’s competitive situation could mess things up for me is if a firm needs to own a large factory to scare off potential rivals, or a small one to reassure its competitors it won’t start a price war. I am going to assume that the firm I am talking about is only renting capital, so that it has no power to credibly signal its intentions with its capital stock.)

The Isoquant. Economists call changes in capital and labor that keep output the same “moving along an isoquant,” since an “isoquant” is the set of points implying the same (“iso”) quantity (“quant”). To keep the amount of output the same, both sides of the percent change version of the Cobb-Douglas equation should be zero:

0 = %ΔY = %ΔA + α %ΔK + (1-α) %ΔL

Since I am treating the level of technology as constant in this post, %ΔA=0. So the equation defining how the Platonic percent changes of capital and labor behave along the isoquant is

0 = α %ΔK + (1-α) %ΔL.

Equivalently,

%ΔL = -[α/(1-α)] %ΔK.

With the realistic value of α=1/3, this would boil down to %ΔL = -.5 %ΔK. So in that case, %ΔK= 1% (a 1 % increase in capital) and %ΔL = -.5 % (a one-half percent decrease in labor) would be a movement along the isoquant–an adjustment in the quantities of capital and labor that would leave output unchanged.

Moving Toward the Least-Cost Way of Producing Output. To find the least-cost or cost-minimizing way of producing output, think of what happens to costs as the firm changes capital and labor in a way that leaves output unchanged. This is a matter of transforming the approximation for the percent change of total costs by

- replacing %ΔR and %ΔW with 0, since nothing the firm does changes the rental price of capital or the wage of labor that it faces;

- replacing %ΔL with -[α/(1-α)] %ΔK in the approximate equation for the percent change of total costs; and

- replacing s_L with 1-s_K.

After Step 1, the result is

%Δ (RK+WL) ≈ {s_K} %ΔK + {s_L} %ΔL.

After doing Step 2 as well,

%Δ (RK+WL) ≈ {s_K} %ΔK - {s_L} {[α/(1-α)] %ΔK}.

Then after Step 3, and collecting terms,

%Δ (RK+WL) ≈ {s_K - (1-s_K) [α/(1-α)]} %ΔK

= { [s_K/(1-s_K)] - [α/(1-α)] } [(1-s_K) %ΔK].

Notice that since the

1-s_K = s_L = the cost share of labor

is positive, the sign of (1-s_K) %ΔK is the same as the sign of %ΔK. To make costs go down (that is, to make %Δ (RK+WL) < 0), the firm should follow this operating rule:

1. Substitute capital for labor (making %ΔK > 0)

if [s_K/(1-s_K)] - [α/(1-α)] < 0.

2. Substitute labor for capital (making %ΔK < 0)

if [s_K/(1-s_K)] - [α/(1-α)] > 0.

Thus, the key question is whether s_K/(1-s_K) is bigger or smaller than α/(1-α). If it is smaller, the firm should substitute capital for labor. If s_K/(1-s_K) is bigger, the firm should do the opposite: substitute labor for capital. Note that the function X/(1-X) is an increasing function, as can be seen from the graph below:

X

Since X/(1-X) gets bigger whenever X gets bigger (at least in the range from 0 to 1 (which is what matters here),

- s_K/(1-s_K) is bigger than α/(1-α) precisely when s_K > α

- s_K/(1-s_K) is smaller than α/(1-α) precisely when s_K < α.

So the firm’s operating rule can be rephrased as follows:

1. Substitute capital for labor (making %ΔK > 0)

if s_K < α.

2. Substitute labor for capital (making %ΔK < 0)

if s_K > α.

This operating rule is quite intuitive. In Case 1, the importance of capital for the production of output (α) is greater than the importance of capital for costs (s_K). So it makes sense to use more capital. In Case 2, the importance of capital for the production of output (α) is less than the importance of capital for costs (s_K), so it makes sense to use less capital.

Proof of the Constant-Share Property of Cobb-Douglas. So what should the firm do in the end? For fixed R and W, the more capital a firm uses, the bigger effect a 1% increase in capital has on costs. So if the firm is using a lot of capital, the cost share of capital will be greater than the importance of capital in production α and the firm should reduce its use of capital, substituting labor in place of capital. If the firm is using only a little capital, the cost share of capital will be smaller than the importance of capital in production α, and it will be a good deal for the firm to increase its use of capital, allowing it to reduce its use of labor. At some intermediate level of capital, the cost share of capital will be exactly equal to the importance of capital in production α, and there will be no reason for the firm to either increase or reduce its use of capital once it reaches that point. So a firm that is minimizing its costs–a first step toward optimizing overall–will produce a given level of output with a mix of capital and labor that makes the cost share of capital equal to the importance of capital in production:

cost-minimization ⇒ s_K = α.

Concordantly, one can say

cost-minimization ⇒ 1-s_K = 1-α.