Universe Price Tiers—xkcd →

Hat tip to Joseph Kimball.

Why Are Young People Having So Little Sex?—Kate Julian →

I was pointed to the interesting long-read linked above by this twitter thread.

How a Toolkit Lacking a Full Strength Negative Interest Rate Option Led to the Current Inflationary Surge

In the third part of our April 7, 2022 “The Future of Inflation” trilogy, “The Electronic Money Standard and the Possibility of a Zero Inflation Target,” Ruchir Agarwal and I write:

Despite the surge in inflation worldwide, central banks have been behind the curve in raising rates. One reason is the reliance on forward guidance instead of negative interest rate policy. At the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, most advanced country central banks lowered their rates to the effective lower bound (but not deeper into negative territory) and thus had to deploy ‘forward guidance’—by committing to maintain the near-zero rates until they were confident that the economy was on track to achieve employment targets. However, such forward guidance tied the hands of several central banks when faced with rising inflation—leading to a sluggish interest response to record-high inflation. Tying their hands with a forward guidance promise was especially unfortunate given the unprecedented nature of the shock.

And for Mitra Kalita’s August 9, 2022 newsletter post “We're Asking the Wrong Question About the Recession,” I crafted two unused quotes (quoting from my email to her):

Because raising rates too late means it is typically necessary to engineer a recession to bring down inflation, the Fed, in effect, caused the coming recession by failing to take decisive action earlier. What might decisive action earlier have looked like? Instead of waiting to raise rates until April 2022 and starting slowly, the Fed should have raised rates by 3/4 of a percentage point in December 2021 and announced that it would keep raising rates by 3/4 of a percentage point at each meeting until it saw clear signs that inflation was headed back all the way to the 2 % target rate. The Fed had enough information by its December 14-15 meeting to make that call.

Thinking falsely that it couldn't fall back on negative rates, the Fed was too slow and timid in raising rates for fear that it didn't have the firepower to quickly reverse a recession if it went too far in raising rates.

Now in his August 26, 2022 Wall Street Journal essay “Can Central Banks Maintain Their Autonomy?” I see that Nick Timiraos, the doyen of monetary policy journalists, takes a similar view of why the Fed and other central banks were behind the curve in raising rates. He writes:

Finally, the pandemic struck just as U.S. and European central bankers were concluding reviews of the policy frameworks they had used to address the problems bedeviling their economies since the 2008 crisis. They wanted to avoid a rut of slow growth and low inflation that would cripple their ability to stimulate the economy in a downturn. They had seen Japan struggle to escape that trap for most of the previous two decades, even after cutting interest rates to zero or below.

At Jackson Hole in 2020, Mr. Powell unveiled an overhauled policy framework. The Fed would aim to return inflation not just to its 2% target but rather to a level a bit above it, so inflation would average 2% over time. For the preceding decade, “We could not get inflation up to 2%,” said Fed governor Christopher Waller. “This sounds crazy. I used to always joke, ‘Go get the guys from Argentina. They know how to do it.’”

Part of the reason Fed officials waited too long to react to the recent surge in inflation is that “they wanted to be sure” that the problem of weak growth and inflation had been vanquished, said Mr. Rajan. “Imagine the hue and cry,” he added, “if they had raised rates immediately: ‘Why are you killing a sound economy?’”

This was in part, a matter of generals fighting the last war rather than the war they are in. But it was more than that. If you thought that fighting the war you are in would destroy all of your hardware for fighting a war like the last war, you could be clear about the war you were in and still hesitate to do what would otherwise be called for.

That is where having a full strength negative interest rate policy in reserve could help. If you know you can cut interest rates as much as necessary to quickly end any recession caused by inadequate aggregate demand, then you can raise rates with the confidence you can get back on track if you make a mistake and overdo it. If you are too afraid to overdo interest rate hikes, you are likely to underdo them. That is what happened.

The Fed has had the opposite problem in the past. In his August 25, 2012 Slate piece “We Need Inflation-Tolerance, Not Inflation,” Matt Yglesias writes:

Imagine you’re watching an Olympic-quality archer who’s having a very bad day. You notice that not only is his overall score much worse than he normally does, but all of his arrows are falling lower than the bullseye. You ask him about it and he tells you that his daughter’s been kidnapped, and the kidnapper says he’ll kill the girl if he shoots a single arrow above the bullseye. Now it all makes sense. The archer hasn’t lost his skill. He’s deliberately aiming too low because he has enormous aversion to shooting above the bullseye. If he lost that aversion, his score would improve.

The moral of the story isn’t that shooting too high is a good way to win an archery tournament. To win, you need to hit the bullseye—neither too high nor too low. But if you become strongly averse to shooting too high, that’s going to undermine your ability to hit the bullseye.

That’s the situation I think American monetary policy is in. It’s not that three or four percent inflation is such a wonderful goal. It’s that extreme aversion to three or four percent inflation is causing the Federal Reserve to persistently “shoot too low” in terms of aggregate demand. Ben Bernanke’s acting as if someone’s holding his daughter hostage. Specifically, the reigning dogma is that if inflation were to go from 2 percent to 3 or 4 percent that long-term expectations might become “unanchored” and drift higher and higher, undermining the “hard won gains” of the Volcker years. But there’s no empirical evidence that this is true, and no particularly strong theoretical reason to believe than the worst-case scenario if inflation tolerance goes wrong is worse that the current strategy of grinding the recession out by letting America’s long-term productive capacity collapse.

In the current context, it is easier to think about trying to hit the moving target of the “right” interest rate. But Matt Yglesias is correct that being too afraid of aiming high will make you aim too low. And being too afraid of aiming low will make you aim too high. The Fed and other central banks need to have tools they are confident can do the job in either direction. Then they can immediately take rates to the level that is their best guess of what is right for the battle they are in, knowing they can swiftly pivot if another threat emerges.

Coda: In the first part of our “The Future of Inflation” trilogy, “Will Inflation Remain High?” Ruchir and I write:

While advanced economy central banks may continue to dislike inflation, their current apparent plans—according to their current dot plots (or the equivalent)—may be behind the curve on what would be required to bring inflation back down. Standard Taylor Rule calculations suggest that it could easily take interest rates as high as 7 percent in several countries to bring inflation down.

This is above the level currently expected by markets. Matt Grossman’s August 26, 2022 news article “Bond Yields Inch Higher After Powell Says Fed Will Hold the Line on Inflation,” reports:

Earlier in the summer, market-based forecasts showed that many investors were second-guessing whether the Fed would wind up raising interest rates as much as central bankers have projected.

In late July, the pricing of derivatives called overnight index swaps estimated the Fed’s benchmark rate would peak at around 3.3% in early 2023 before moving lower again.

At the time, that was a much different outlook than the one espoused by Fed officials themselves, who have generally said they expect rates will have to hold steady or climb next year to corral inflation.

In recent sessions, traders’ forecasts have moved closer to the Fed’s. On Friday, derivatives traders were now projecting that rates will rise to nearly 3.8% by the end of the Fed’s May 2023 policy meeting.

3.8% is still a lot lower than the 7% or so I think will be necessary to bring inflation back to the 2% per year target. Since I believe the Fed is committed to getting inflation under control, I predict further market surprises as market participants and the Fed itself realize how high rates need to go.

See also:

Noah Smith: 4 Reasons Why GDP is a Useful Number →

This post by Noah looks great for teaching.

An Example of Needing to Worry about Reverse Causality: Satisfaction with Aging and Objective Aging Outcomes

Though there are some places where the wording is cautious, there is a strong desire in this journal article, and the associated news articles, to make the interpretation that having a better attitude toward aging will result in better objective aging outcomes. That might be true, and seems likely to at least be true at a low effect size. But the “association” or correlation between aging satisfaction (the measuring of attitude toward aging) and objective aging outcomes could easily be an instance of people having a sense of their own health status that goes beyond easily tallied objective outcomes and having a worse attitude toward aging because they already know their health is poor.

I don’t see how the effect of attitude toward aging on objective aging outcomes can be identified without a randomized controlled trial of an intervention trying to improve attitudes toward aging. Note that getting a placebo here is a little tricky. It requires something like an intervention to change an attitude thought to be irrelevant to aging outcomes.

If one considers underlying health status to be distinct from easily tallied health outcomes, then one could see this as “Cousin Causality” from underlying [health status] affecting both [aging satisfaction] and [later easily tallied bad health outcomes]. A virtue of seeing this as an instance of cousin causality (sometimes called “third-factor causality”) as opposed to reverse causality is that it makes clearer that the aging satisfaction being measured earlier in time than the easily tallied health outcomes doesn’t mean the aging satisfaction caused the health outcomes. The ancestor factor affecting both can easily be earlier in time than both. Then on one branch we are saying that poor underlying health begets bad easily tallied health outcomes, which seems like a truism.

In the conclusion, the authors Julia S. Nakamura, Joanna H. Hong, and Jacqui Smith write:

… there is potential for confounding by third variables. However, we addressed this concern by implementing a longitudinal study design, robust covariate adjustment, and E-value analyses.

“Longitudinal study design” could mean two things: one, having aging satisfaction measured before easily tallied health outcomes. That doesn’t solve a problem of “confounding by third variables,” which is another way of describing cousin causality, for the reason I said above: the third ancestor variable can easily be before both aging satisfaction and easily tallied health outcomes. The other thing “longitudinal study design alludes to is a focus on changes in aging satisfaction. But changes in aging satisfaction can easily be due to changes in underlying health status, and everything I say above goes through. “Robust covariate adjustment” doesn’t solve the problem of confounding because subjective health measures contain information that goes beyond all of the other health measures in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS); research shows that subjective health measures add predictive power for later easily tallied health outcomes beyond other covariates in the HRS. I am suggesting that aging satisfaction has to be considered as being analogous to the subjective health measures in the HRS. Note that doesn’t mean controlling for subjective health would solve the problem either, because subjective health is surely measured with error. (See “Adding a Variable Measured with Error to a Regression Only Partially Controls for that Variable.” Having aging satisfaction as a second measure of subjective health ought to increase predictive power over only one measure of subjective health. Finally, the “E-value analyses” simply say that the story for why there might be confounding would have to be one that makes a lot of confounding plausible. I think that is satisfied by the story I give above.

A Linear Model for the Effects of Diet and Exercise on Health is a Big Advance over Popular Thinking

It is easy to take for granted what one is good at. (On this, see “How to Find Your Comparative Advantage.”) Economists often don’t appreciate the sophistication of the models they deal with in comparison to common ways of thinking. I point out to my undergraduate students that, relative to “P affects Q and Q affects P; it is the seamless web of history that can’t be untangled,” supply and demand is a big advance. And I point out to my graduate students how holding a co-state variable fixed as a step in the analysis of a phase diagram even when it won’t be fixed in the end is fully analogous to holding price fixed to develop supply and demand curves, that then make it possible to cleanly analyze equilibrium effects in which price is not fixed.

Another key example is this: relative to the idea that there are only two possibilities, A or B, that C is the one cause of D, or that either E or F are enough to get from one of two states to another, a model in which two different things have a linear effect on an outcome is a big advance. The two articles flagged above show the value of even a simple linear model for understanding, diet, health and exercise. Both eating right and exercising are valuable for health, and doing one doesn’t reduce the marginal product of the other that much. And the curvature in the effect of exercise on health isn’t big enough to keep more than the usually recommended amount of exercising from having a substantial positive effect.

Of course, the linear model, while almost always a good approximation locally, almost always breaks down eventually due to curvature. On that, see “The Golden Mean as Concavity of Objective Functions.” But note that a model with gradual curvature is strictly more complex than a linear model. A linear model is a key stepping-stone on the way to understanding a model with gradual curvature.

When I previewed the content of this post for one of my friends, the reaction was that this sounded like looking down on others. I don’t view it that way. We need to see what we are good at and what is hard for others in order to do the most good in the world. And conversely, we need to see what others are good at that is hard for us. And of course, we need to see what we and others are relatively good at. That is the essence of comparative advantage. It is a matter of mathematics that everyone has some comparative advantage! (At least weakly.)

Recognizing your own technical advantages makes it clearer what you have to offer, and the efforts you will need to make to explain an idea clearly given where your listeners are coming from. One of the best pieces of advice I ever got was one of the excerpts I was given from letters of evaluation when I came up for tenure. One writer said “Miles sometimes overestimates his audiences.” The translation is that what I was saying was obscure because I hadn’t given the appropriate background or had gone too fast.

People can be offended by being treated as if they have less background than they do, and on the other hand, they can be confused by being treated as if they have background that they don’t. There is no way around the need to get it right.

How Covid Worsened Antibiotic Resistance; What We Need to Avoid Getting Slaughtered by Superbugs

Here are two key passages from the article flagged above, separated by added bullets:

A superbug is a bacterium or fungi that is resistant to clinical antimicrobials. They are increasingly common. Right now, for instance, the percentage of clinical isolates of Enterobacteriales (which includes things like Salmonella and E. coli) that are known to be resistant is around 35%.

… we need to discover and develop novel classes of antibiotics. The last time a new class of antibiotics hit the market was in 1984. The fundamental problem is that they’re not profitable to develop, compared to say a cancer drug. You can go to the drugstore and get a course of amoxicillin for $8. We need programs that reward industry and academic labs like ours for doing the early research.

Mitra Kalita asks Miles Kimball, Cecilia Rouse and Daniel Zhou about the Coming Recession →

Mitra Kalita is the best editor I ever had. See worked with me on most of the Quartz columns you can see in my “Key Posts” bibliography. (which is also a button at the top of this page). I am very proud of those columns, and Mitra is a big part of why they are worthy of that pride.

Mitra caught up with me recently and asked me about the coming recessions. You can see the article she wrote at the link on the title of this post and here.

25 Taboo Questions About History and Society—Rudyard Lynch

Screen shot from “Another 7 Taboo Questions About History and Society”

Rudyard Lynch has done a good job in these 3 videos of identifying 25 important questions that are, indeed, difficult to talk about in current polite society. I think it is important to talk about such questions. However you come down on these questions, it is better to mull them over and decide what you think than it is to shut your eyes to such questions.

What David Laibson and Andrei Shleifer are Teaching for Behavioral Economics—Jeffrey Ohl

The majority of my research time for many years has gone to the effort to develop the principals for a well-constructed National Well-Being Index. We (Dan Benjamin, Ori Heffetz, Kristen Cooper and I) call this the “Well-Being Measurement Initiative.” Every year, we choose a full-time RA, serving for two years in an overlapping generations structure that gives us two full-time RAs at a time. We have a very rigorous hiring process. Jeffrey Ohl survived that process and is doing an excellent job. This guest post is from him. Since our full-time RAs sit at the NBER, it was easy for him to audit a course at Harvard. Below are Jeffrey’s words.

This post summarizes what I learned auditing Economics 2030 at Harvard University from January - May of 2022. I am grateful to Professor David Laibson and Professor Andrei Shleifer for letting me take this course.

Behavioral economics aims to provide more realistic models of people’s actions than the Neoclassical paradigm epitomized by expected utility theory. Expected utility theory (and its compatriot, Bayesian inference), assumes people’s preferences are stable and that people can and do rationally incorporate all available information when making decisions. The implications often violate common-sense—people buy lottery tickets, have self-control problems, and fail to learn from their mistakes.

For decades, the rational benchmark was defended. Milton Friedman’s “as-if” defense is that assumptions don’t need to be accurate: they only need to make correct predictions. For example, a model that assumes a billiards player calculates the equations to determine the path of the billiards balls may predict his choice of shots quite well, even though he makes his shots only off intuition. Similarly, Friedman argued, people might not think about maximizing utility moment-to-moment, but if people make choices as if they were, then the rationality assumption is justified when making predictions. Another argument—also by Milton Friedman—is evolutionary. Even if most investors are not rational, the irrational ones make fewer profits over time, leaving only the rational investors to conduct transactions of meaningful size.

But over the last 30 years, behavioral economics has become more widely accepted in the economics profession. Richard Thaler served as president of the American Economic Association in 2015 and won a Nobel Prize in Economics in 2017, Daniel Kahneman (a psychologist) received the Nobel in 2002, and John Bates Clark medals went to Matthew Rabin (1999), Andrei Shleifer (2001, and Raj Chetty (2013).

This post will thus not discuss issues with assuming rationality in economic models, to which Richard Thaler’s Misbehaving and Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slowly are superb popular introductions. David Laibson also has an excellent paper on how behavioral economics has evolved (Behavioral Economics in the Classroom). Instead I will discuss some debates within behavioral economics

Prospect Theory and its flaws

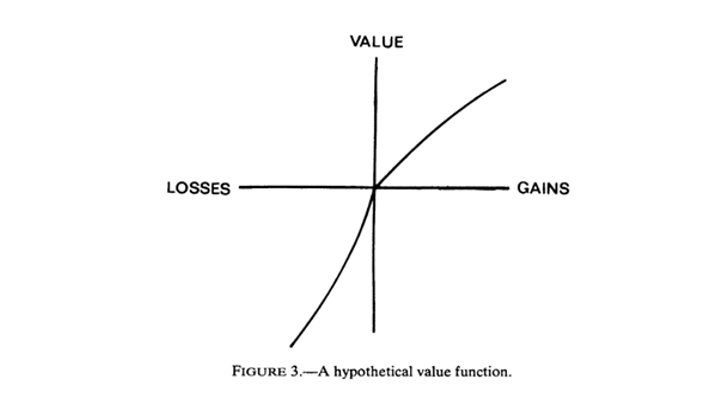

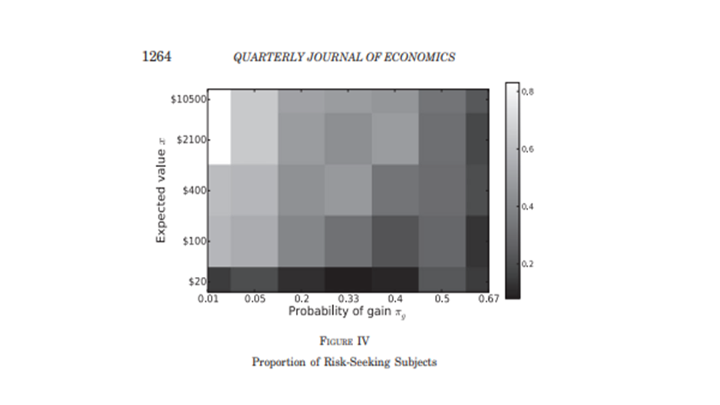

One of the most highly cited papers in the social sciences is the 1979 paper Prospect Theory by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky (KT). In it, KT propose an alternative to expected utility, prospect theory, which is summarized in two famous graphs.

The first is the value function, which includes (a) diminishing sensitivity to both losses and gains, (b) loss aversion, and (c) the fact that gains and losses are assessed relative to a reference point, rather than in absolute terms. Loss aversion has been fairly well validated, for example a 2010 paper by Justin Sydnor shows that people choose home insurance deductibles in a way that risk aversion alone cannot explain[1]. Other animals may even exhibit loss aversion.

The more contested figure of the two is the probability weighting function (PWF). The PWF posits that people “smear” probabilities towards 0.5 -- they overestimate small probabilities and underestimate large ones (sometimes called the certainty effect).

The PWF is attractive. If true, it can parsimoniously explain why people buy lottery tickets with negative expected value, as well as overpriced rental car insurance.

But there are several issues with the PWF.

First, it assumes that people make decisions based on numerical probabilities. But this is rarely how we assess risk. In practice, we are exposed to a process - for example, the stock market, and need to learn how risky it is with experience. It turns out this difference matters. Hertwig and Erev showed that when told a numerical probability vs having to infer it from repeated exposure to gambles, people make different choices.

Another weakness of the PWF is that it doesn’t depend on the magnitudes of the losses and gains in a gamble, only their objective probability, p. In a 2012 paper, Bordalo, Gennaioli, and Shleifer (BGS) propose an alternative theory, salience theory, which captures a key intuition: people pay more attention to large changes when assessing gambles, holding probabilities constant. BGS tested this claim experimentally and found that subjective probabilities did indeed depend on the stakes in the experiment, whereas the PWF would predict the below plot to show no variation in the y-axis—the stakes should not matter.

Salience theory can also neatly explain preference reversals that PT cannot. For example, Liechtenstein and Slovic found that subjects gave a higher willingness-to-pay for Lottery A than Lottery B, but chose Lottery B over Lottery A when asked to pick between the two. Under prospect theory, this should not occur. But under salience theory, the differing salience of the lottery payoffs between the two settings can explain this reversal. Many other applications of salience in economics are discussed in this literature review.

The limitations of nudges

Behavioral economics’ largest influence on public policy is probably via “nudges”. Nudges subtly modify people’s environments in ways that help satisfy their goals without reducing their choice set. Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler discuss nudges in-depth in their eponymous best-selling book. I learned that nudges are often of limited effectiveness, despite the initial excitement.

For example, one famous nudge is to make 401(k) plans “opt-out”, rather than “opt-in”, or automatic enrollment (AE). One of the first studies on the effects of AE was a 2001 Madrian and Shea paper. In 2004, Choi, Laibson, Madrian and Metrick did a follow-up study and found that when the study’s effects were extended from 12 to 27 months, auto-enrollment had approximately zero impact on wealth accumulation. The initial benefits of the nudge were offset because it anchored certain employees at a smaller savings rate than they otherwise might have chosen, and because the default fund had a conservative allocation.

A similar flop occurred in the credit card domain. Adams, Guttman-Kenney, Hayes, Hunt, Laibson and Stewart found that a fairly aggressive nudge, which completely removed the button allowing credit card customers to pay only the minimum amount, did not have a significant effect on total repayments, or credit card debt. Borrowers mainly compensated for the nudge by making fewer small payments throughout the month.

Laibson summarizes the results of two decades of nudges in the table at the top of this post, which is excerpted from his 2020 AEA talk. Two features stand out: 1) the short-run impact of nudges is often larger than the long-run impact because habits, societal pressures, etc. pull people back to their pre-nudge behavior and 2) large welfare effects from nudges are rare. However, small effect sizes can still imply cost effectiveness, since the costs of nudges are small. Both extreme optimism and pessimism for nudges seem unwarranted.

A unifying theory for behavioral economics to replace EU theory?

One of the main critiques against behavioral economics is that is has no unifying theory.

Anyone familiar with KT’s heuristics-and-biases program will know the slew of biases and errors they found: the availability heuristic, the representativeness heuristic, the conjunction fallacy, etc. These biases often conflict and there is no underlying theory that makes predictions about when one dominates over another.

For example, suppose I’m asked to estimate the percentage of people in Florida who are over 55, after having just visited friends in Florida. The representativeness heuristic suggests I’d overestimate this percentage, since Florida has more older people than other states, and thus being over 55 is representative of being from Florida. But the availability heuristic implies I’d mainly recall the young people who I just saw in Florida, causing me to underestimate the share of older people in the state. What does behavioral economics predict?

Rational actor models sidestep these issues by having a small set of assumptions that—even if not exactly true - are reasonable enough that most economists view them as good approximations. This had led to rational choice serving as a common language among economists - when theories are written using this language, their assumptions can be transparently criticized. But when behavioral biases are introduced ad hoc, it makes comparing theories difficult.

The inertia of a unifying theory means that even if it’s not perfect, rational actor models will probably remain the primary way economists talk to each other unless a replacement comes along.

In a series of recent papers, BGS and co-authors have begun to outline such a replacement. In papers such as Memory and Representativeness, Memory, Attention and Choice, and Memory and Probability, they micro-found decision-making in the psychology of attention and of memory. This research program predicts the existence of many biases originally discovered piecemeal by psychologists, as well as new ones. Rather than making small tweaks to existing models, they start with a biological foundation for predicting how people judge probabilities and value goods, and see where it goes.

For example, Memory and Probability assumes people (a) estimate probabilities by sampling from memory, and (b) are more likely to recall events that are similar to a cue, even if those events are irrelevant. Granting these assumptions predicts the availability heuristic, the representativeness heuristic, and the conjunction fallacy. The advantage of this unified approach is that researchers don’t need to weigh one bias against another, rather, many biases are nested in a theory that makes a single prediction.

The paper also predicts a new bias, which the authors validate experimentally. The bias is over-estimation of the probability of “homogenous” classes of events, i.e. classes where all the events are self-similar, for example, “death from a flood”. Similarly, they underestimate the likelihood of “heterogenous” classes, e.g. “death from causes other than a flood.”

In closing, one of the most important challenges in making economics models more accurate will be to develop a theory that incorporates the quirks of how our brains actually work while remaining mathematically tractable enough to be adopted by the economics profession.

[1] Some studies, however, have shown that loss aversion is reduced with training and proper incentives. The original PT paper was also ambiguous about how the reference point from which gains/losses are assessed is formed.