Supply and Demand for the Monetary Base with a Cap on Reserves, a Zero Interest Rate on Reserves and a Negative Reverse Repo Rate

This post assumes you have read “Supply and Demand for the Monetary Base: How the Fed Currently Determines Interest Rates” and “How the Fed Could Use Capped Reserves and a Negative Reverse Repo Rate Instead of Negative Interest on Reserves.” This diagram combines the argument of those two posts. Note that in the situation diagrammed above the interest rate is negative (say an annual rate of -2%) even though the interest rate on reserves is zero.

In the graph above, the vertical portion of the demand for the monetary base is at the cap, which technically is on reserves, but is effectively on reserves plus currency because the cap on reserves declines 1 for 1 with any increase in currency and rises with any reduction in currency.

Two Terminological Issues

What is the Monetary Base in this Situation? In this system, it would make sense to measure the monetary base not as currency + reserves, but as currency + reserves + reverse repo-based loans to the Fed. If one insists on measuring the monetary base as currency + reserves, then the monetary base would be much larger in the daytime when reverse repo balances have turned back into reserves. (There is no cap on reserves in the daytime. Only at night.) So measuring the monetary base as currency + reserves + reverse repo-based loans to the Fed is equivalent to a daytime measure of currency + reserves.

By the way, I would like to get clear whether, currently, the monetary base is measured by its daytime value or its nighttime value. Reverse repo balances are already substantial.

What Should We Call Reserves Over the Cap? I have found myself tempted to call reserves over the cap “excess reserves,” which of course won’t do because “excess reserves” is already in use for reserves beyond required reserves. I propose “overcap reserves” for reserves beyond the cap that get routinely swept into the reverse-repo-based overnight facility every evening. “Overcap reserves” is short and pithy and gets the job done.

How People Differ from One Another Psychologically: IQ and the Big 5—Jordan Peterson

This particular class is a great introduction to IQ and to personality theory in psychology. Also, Jordan Peterson does a great job of skewering the twisting of psychology to tell people what they want to hear. In particular, (a) IQ is a very well-defined measure (with such strong correlations between different problem-solving skills that it looks to be dominated by one factor), (b) IQ does a great job of predicting important things and (c) very few psychological trait concepts add anything beyond IQ and the Big 5 personality traits or IQ and the Big 10 that come from splitting each of the Big 5 into 2 (although showing how things with other names relate to IQ and the Big 5 or Big 10 can be quite illuminating).

Highly recommended for economists who want to quickly learn key concepts from an area of psychology quite relevant to economics, but different from the social psychology that is most similar to experimental economics.

One conjecture: I suspect that measures of economic preference parameters do tend to be distinct from IQ and the Big 5. But if not, the way preference parameters could be predicted by IQ and the Big 5 would be quite interesting.

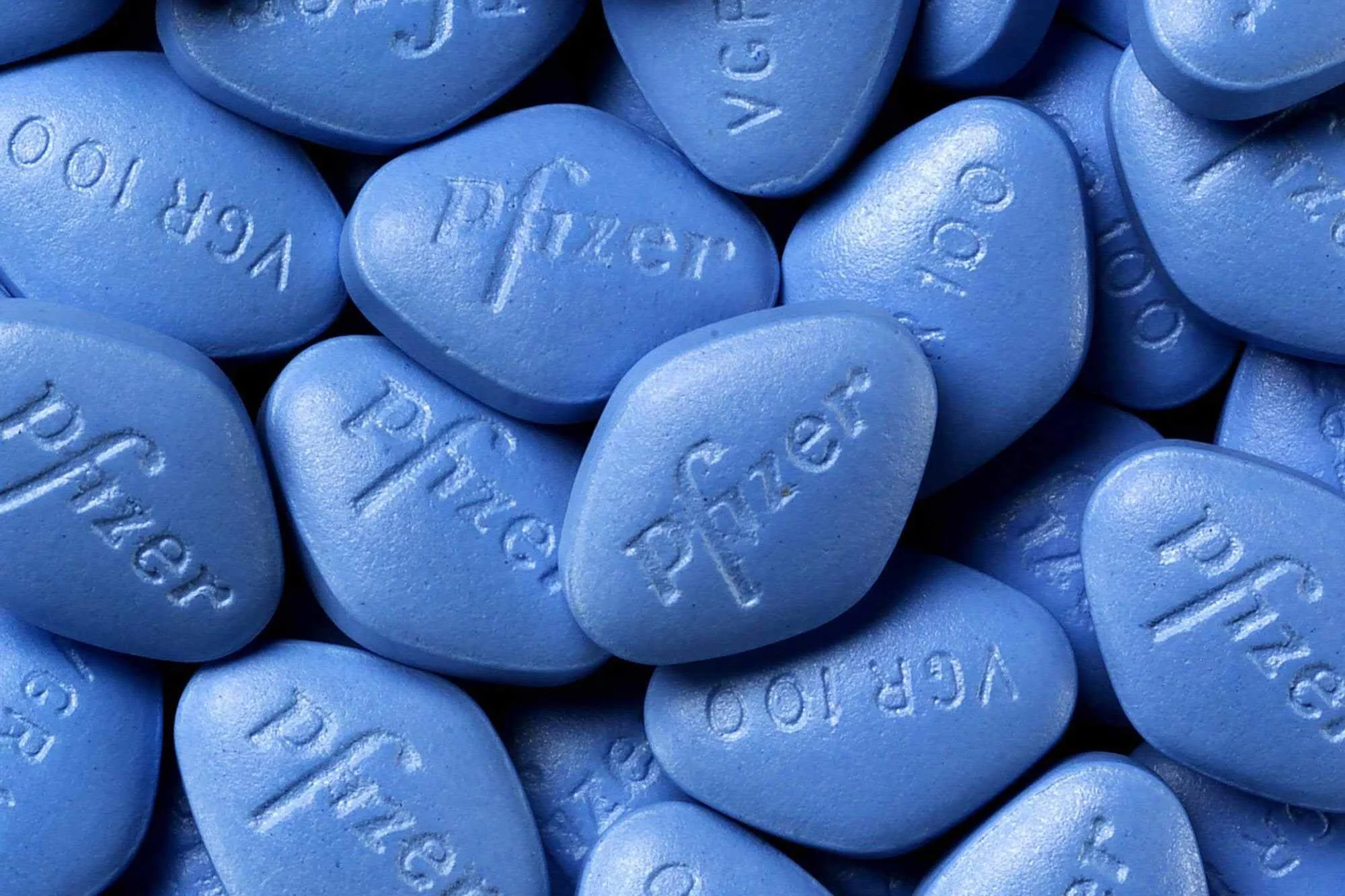

In Praise of Sildenafil

I’ll turn 62 in a few months. So I don’t feel too embarrassed about having mild erectile dysfunction. Fortunately, Sildenafil—better known under one of its marketing names, Viagra—works like a charm. Or more precisely, I should say it is like clockwork. (For me, Tadalafil—better known under its marketing name Cialis—does almost nothing. I’m sure it works great for many others.)

The reason I am saying this is that mentioning it out in the open might help you get over resistance to looking into some chemical help if you are beginning to need it. Everyone is different, but for many men, erectile dysfunction is a concomitant of aging, just like needing reading glasses. Others run into this relatively easily fixable trouble earlier.

When I teach financial theory, I compare diversifiable risk to a malady that can easily be cured. For many men, this is in that category. Don’t suffer needlessly. Try available potential remedies to see if they work for you.

One thing that led me to delay trying Sildenafil was the fear that it would interact badly with my low blood pressure. That turned out not to be a problem at all.

By the way, looking for an image to put at the top of this post revealed that a lot of research is being done to see if sildenafil can be useful in dealing with other maladies. Those research efforts make sense because it expands blood vessels, leading to more blood flow throughout the body, something that could be useful in many situation.

I’m glad for progress. Sildenafil was approved for treatment of erectile dysfunction only in 1998. So as an approved drug, it is less than a quarter century old. It’s good not to live in the bad old days.

For annotated links to other posts on diet and health, see:

The Federalist Papers #52: On the Franchise + Elections to the House of Representatives Every Two Years are Frequent Enough to Preserve Liberty

The Federalist Papers #52, written by either Alexander Hamilton or James Madison, only tries to accomplish two things. First, it argues it frames the constitutional requirement of having the same franchise in any state for the US House of Representatives as for the corresponding part of the state’s legislature as prevention against excessive strategic game-playing through manipulation of the franchise for the US House of Representatives by either the federal or state governments. There is a hint that reducing state power further than that by specifying the franchise did not seem feasible in 1787:

To have reduced the different qualifications in the different States to one uniform rule, would probably have been as dissatisfactory to some of the States as it would have been difficult to the convention.

Of course, later amendments to the US Constitution did specify the franchise more tightly (bullets added):

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude— [from the 15th amendment]

The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. [from the 19th amendment]

The right of citizens of the United States to vote in any primary or other election for President or Vice President, for electors for President or Vice President, or for Senator or Representative in Congress, shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State by reason of failure to pay poll tax or other tax. [from the 24th amendment]

The right of citizens of the United States, who are eighteen years of age or older, to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of age. [from the 26th amendment]

In addition, Section 2 of the 14th amendment imposes a penalty for limiting the franchise in other ways, such as by wealth:

… when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice-President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the Executive and Judicial officers of a State, or the members of the Legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age,* and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such State. [from the 14th amendment]

I think a constitutional amendment modernizing this idea would be very interesting. Suppose that instead of the number of representatives a state gets being determined by a population count, it was determined by the number of people who voted in the last few federal elections. Then every state has an incentive to increase voter participation. As a good complementary idea that might make this idea more appealing to Republicans, this could be coupled with regular audits of the people who voted to make sure that ineligible voters were not counted. Even if such an amendment couldn’t pass, I think those opposing it would look bad.

The second thing the Federalist Papers #52 tries to accomplish is to argue that every 2 years is often enough for elections to the US House of Representatives. The argument boils down to citing examples of many other governments in which the corresponding legislative body is subject to elections less often or equally often, and claiming that, by and large, these showed real concern for the opinions of the people. That brief summary captures the essence of this part of the Federalist Papers #52. The full text is below.

FEDERALIST NO. 52

The House of Representatives

From the New York Packet

Friday, February 8, 1788.

Author: Alexander Hamilton or James Madison

To the People of the State of New York:

FROM the more general inquiries pursued in the four last papers, I pass on to a more particular examination of the several parts of the government. I shall begin with the House of Representatives. The first view to be taken of this part of the government relates to the qualifications of the electors and the elected. Those of the former are to be the same with those of the electors of the most numerous branch of the State legislatures.

The definition of the right of suffrage is very justly regarded as a fundamental article of republican government. It was incumbent on the convention, therefore, to define and establish this right in the Constitution. To have left it open for the occasional regulation of the Congress, would have been improper for the reason just mentioned. To have submitted it to the legislative discretion of the States, would have been improper for the same reason; and for the additional reason that it would have rendered too dependent on the State governments that branch of the federal government which ought to be dependent on the people alone. To have reduced the different qualifications in the different States to one uniform rule, would probably have been as dissatisfactory to some of the States as it would have been difficult to the convention. The provision made by the convention appears, therefore, to be the best that lay within their option.

It must be satisfactory to every State, because it is conformable to the standard already established, or which may be established, by the State itself. It will be safe to the United States, because, being fixed by the State constitutions, it is not alterable by the State governments, and it cannot be feared that the people of the States will alter this part of their constitutions in such a manner as to abridge the rights secured to them by the federal Constitution. The qualifications of the elected, being less carefully and properly defined by the State constitutions, and being at the same time more susceptible of uniformity, have been very properly considered and regulated by the convention. A representative of the United States must be of the age of twenty-five years; must have been seven years a citizen of the United States; must, at the time of his election, be an inhabitant of the State he is to represent; and, during the time of his service, must be in no office under the United States. Under these reasonable limitations, the door of this part of the federal government is open to merit of every description, whether native or adoptive, whether young or old, and without regard to poverty or wealth, or to any particular profession of religious faith. The term for which the representatives are to be elected falls under a second view which may be taken of this branch. In order to decide on the propriety of this article, two questions must be considered: first, whether biennial elections will, in this case, be safe; secondly, whether they be necessary or useful. First. As it is essential to liberty that the government in general should have a common interest with the people, so it is particularly essential that the branch of it under consideration should have an immediate dependence on, and an intimate sympathy with, the people. Frequent elections are unquestionably the only policy by which this dependence and sympathy can be effectually secured. But what particular degree of frequency may be absolutely necessary for the purpose, does not appear to be susceptible of any precise calculation, and must depend on a variety of circumstances with which it may be connected. Let us consult experience, the guide that ought always to be followed whenever it can be found. The scheme of representation, as a substitute for a meeting of the citizens in person, being at most but very imperfectly known to ancient polity, it is in more modern times only that we are to expect instructive examples. And even here, in order to avoid a research too vague and diffusive, it will be proper to confine ourselves to the few examples which are best known, and which bear the greatest analogy to our particular case. The first to which this character ought to be applied, is the House of Commons in Great Britain. The history of this branch of the English Constitution, anterior to the date of Magna Charta, is too obscure to yield instruction. The very existence of it has been made a question among political antiquaries. The earliest records of subsequent date prove that parliaments were to SIT only every year; not that they were to be ELECTED every year. And even these annual sessions were left so much at the discretion of the monarch, that, under various pretexts, very long and dangerous intermissions were often contrived by royal ambition. To remedy this grievance, it was provided by a statute in the reign of Charles II. , that the intermissions should not be protracted beyond a period of three years. On the accession of William III. , when a revolution took place in the government, the subject was still more seriously resumed, and it was declared to be among the fundamental rights of the people that parliaments ought to be held FREQUENTLY. By another statute, which passed a few years later in the same reign, the term "frequently," which had alluded to the triennial period settled in the time of Charles II. , is reduced to a precise meaning, it being expressly enacted that a new parliament shall be called within three years after the termination of the former. The last change, from three to seven years, is well known to have been introduced pretty early in the present century, under on alarm for the Hanoverian succession. From these facts it appears that the greatest frequency of elections which has been deemed necessary in that kingdom, for binding the representatives to their constituents, does not exceed a triennial return of them. And if we may argue from the degree of liberty retained even under septennial elections, and all the other vicious ingredients in the parliamentary constitution, we cannot doubt that a reduction of the period from seven to three years, with the other necessary reforms, would so far extend the influence of the people over their representatives as to satisfy us that biennial elections, under the federal system, cannot possibly be dangerous to the requisite dependence of the House of Representatives on their constituents. Elections in Ireland, till of late, were regulated entirely by the discretion of the crown, and were seldom repeated, except on the accession of a new prince, or some other contingent event. The parliament which commenced with George II. was continued throughout his whole reign, a period of about thirty-five years. The only dependence of the representatives on the people consisted in the right of the latter to supply occasional vacancies by the election of new members, and in the chance of some event which might produce a general new election.

The ability also of the Irish parliament to maintain the rights of their constituents, so far as the disposition might exist, was extremely shackled by the control of the crown over the subjects of their deliberation. Of late these shackles, if I mistake not, have been broken; and octennial parliaments have besides been established. What effect may be produced by this partial reform, must be left to further experience. The example of Ireland, from this view of it, can throw but little light on the subject. As far as we can draw any conclusion from it, it must be that if the people of that country have been able under all these disadvantages to retain any liberty whatever, the advantage of biennial elections would secure to them every degree of liberty, which might depend on a due connection between their representatives and themselves. Let us bring our inquiries nearer home. The example of these States, when British colonies, claims particular attention, at the same time that it is so well known as to require little to be said on it. The principle of representation, in one branch of the legislature at least, was established in all of them. But the periods of election were different. They varied from one to seven years. Have we any reason to infer, from the spirit and conduct of the representatives of the people, prior to the Revolution, that biennial elections would have been dangerous to the public liberties? The spirit which everywhere displayed itself at the commencement of the struggle, and which vanquished the obstacles to independence, is the best of proofs that a sufficient portion of liberty had been everywhere enjoyed to inspire both a sense of its worth and a zeal for its proper enlargement This remark holds good, as well with regard to the then colonies whose elections were least frequent, as to those whose elections were most frequent Virginia was the colony which stood first in resisting the parliamentary usurpations of Great Britain; it was the first also in espousing, by public act, the resolution of independence.

In Virginia, nevertheless, if I have not been misinformed, elections under the former government were septennial. This particular example is brought into view, not as a proof of any peculiar merit, for the priority in those instances was probably accidental; and still less of any advantage in SEPTENNIAL elections, for when compared with a greater frequency they are inadmissible; but merely as a proof, and I conceive it to be a very substantial proof, that the liberties of the people can be in no danger from BIENNIAL elections. The conclusion resulting from these examples will be not a little strengthened by recollecting three circumstances. The first is, that the federal legislature will possess a part only of that supreme legislative authority which is vested completely in the British Parliament; and which, with a few exceptions, was exercised by the colonial assemblies and the Irish legislature. It is a received and well-founded maxim, that where no other circumstances affect the case, the greater the power is, the shorter ought to be its duration; and, conversely, the smaller the power, the more safely may its duration be protracted. In the second place, it has, on another occasion, been shown that the federal legislature will not only be restrained by its dependence on its people, as other legislative bodies are, but that it will be, moreover, watched and controlled by the several collateral legislatures, which other legislative bodies are not. And in the third place, no comparison can be made between the means that will be possessed by the more permanent branches of the federal government for seducing, if they should be disposed to seduce, the House of Representatives from their duty to the people, and the means of influence over the popular branch possessed by the other branches of the government above cited. With less power, therefore, to abuse, the federal representatives can be less tempted on one side, and will be doubly watched on the other.

PUBLIUS.

Links to my other posts on The Federalist Papers so far:

The Federalist Papers #1: Alexander Hamilton's Plea for Reasoned Debate

The Federalist Papers #3: United, the 13 States are Less Likely to Stumble into War

The Federalist Papers #4 B: National Defense Will Be Stronger if the States are United

The Federalist Papers #5: Unless United, the States Will Be at Each Others' Throats

The Federalist Papers #6 A: Alexander Hamilton on the Many Human Motives for War

The Federalist Papers #11 A: United, the States Can Get a Better Trade Deal—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #12: Union Makes it Much Easier to Get Tariff Revenue—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #13: Alexander Hamilton on Increasing Returns to Scale in National Government

The Federalist Papers #14: A Republic Can Be Geographically Large—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #21 A: Constitutions Need to be Enforced—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #24: The United States Need a Standing Army—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #27: People Will Get Used to the Federal Government—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #30: A Robust Power of Taxation is Needed to Make a Nation Powerful

The Federalist Papers #35 A: Alexander Hamilton as an Economist

The Federalist Papers #35 B: Alexander Hamilton on Who Can Represent Whom

The Federalist Papers #36: Alexander Hamilton on Regressive Taxation

The Federalist Papers #39: James Madison Downplays How Radical the Proposed Constitution Is

The Federalist Papers #41: James Madison on Tradeoffs—You Can't Have Everything You Want

The Federalist Papers #42: Every Power of the Federal Government Must Be Justified—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #44: Constitutional Limitations on the Powers of the States—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #45: James Madison Predicts a Small Federal Government

The Federalist Papers #48: Legislatures, Too, Can Become Tyrannical—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #49: Constitutional Conventions Should Be Few and Far Between

The Federalist Papers #50: Periodic Commissions to Judge Constitutionality Won't Work

The Federalist Papers #51 A: Checks and Balance, or ‘Who Guards the Guardians?'

Ruchir Agarwal and Miles Kimball on Negative Interest Rates and Inflation—IMF Podcasts

Here is the summary for the podcast shown above:

Everyone feels the pinch when inflation is on the rise and so the pressure on central banks to manage inflation rates has grown exponentially in recent weeks. In this first podcast of a two-part series on inflation, distinguished economists Miles Kimball and Ruchir Agarwal discuss how a robust negative interest rate policy can help central banks better control inflation and stabilize the economy.

Here are other ways you can listen to this podcast:

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/miles-kimball-ruchir-agarwal-on-inflation-part-1-negative/id1029134681?i=1000556697465Libsyn: https://imfpodcast.libsyn.com/miles-kimball-ruchir-agarwal-on-inflation-part-1-negative-interest-rates

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/episode/5JPi2ZPcp8lJAdTWiguaol?si=be381b1b43bd419d

SoundCloud: https://soundcloud.com/imf-podcasts/miles-kimball-ruchir-agarwal

Google Podcasts: https://podcasts.google.com/feed/aHR0cDovL2ltZnBvZGNhc3QuaW1mcG9kY2FzdHMubGlic3lucHJvLmNvbS9yc3M

IMF.org (the link on the image above): https://www.imf.org/en/News/Podcasts/All-Podcasts/2022/04/08/kimball-agarwal-inflation-part-1

The summary for Part 2 is:

Most people and virtually all businesses now use electronic money for their transactions, yet central banks are still dealing with what's known among economists as the paper currency problem, which limits central banks' ability to use deep negative rates to fight recessions. In this second episode of a two-part series on inflation, economists Miles Kimball and Ruchir Agarwal discuss how fully committing to an electronic money standard would allow central banks to break the zero lower bound associated with paper currency and help them to fight both inflation and recessions more effectively, including by lowering the inflation target.

Here are the links for Part 2:

Apple Podcasts: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/ruchir-agarwal-and-miles-kimball-on-electronic-money/id1029134681?i=1000557514550

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/episode/2MlYrqXAsJK9aiJj2gENoS?si=03b118c8d3ba4c10

Libsyn: https://imfpodcast.libsyn.com/ruchir-agarwal-and-miles-kimball-on-electronic-money-and-inflation

SoundCloud: https://soundcloud.com/imf-podcasts/ruchir-agarwal-and-miles

Google Podcasts: https://bit.ly/3uEJACU

IMF.org: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Podcasts/All-Podcasts/2022/04/13/inflation-part-2

The Future Promise of Heirloom Fruit

Link to the “Peach Varieties Guide” shown above. There are a large number of known varieties of peaches.

One of my students asked me, partly in jest, if I had any entrepreneurial ideas for getting rich. I said I thought I had one. Our culture is gradually getting clear that sugar is very, very bad for you. And at some point people will realize that the sugar in fruit is a problem, too. My prediction is that, 20 years from now, low-sugar varieties of fruit will be a thing, and that getting in early in growing and distributing low-sugar varieties of fruit could be a good business move.

My quick summary about fruit is that the sugar in it is quite bad, and the other stuff in fruit is really good for you. So for health, what we need is low-sugar fruit. And it is easy for a grower to both select low-sugar varieties and to breed fruit to have even lower levels of sugar.

Because, commercially, only a few varieties of fruit dominate the market, everything else, by count almost all varieties of edible fruit, count as “heirloom fruit.” Because the market so far has selected for and bred varieties of fruit with high levels of sugar, and made those varieties especially common in stores, many heirloom varieties have lower levels of sugar than the varieties in the store. (Of course, the most popular heirloom varieties could be exactly those that have even higher levels of sugar than those in the store, but say are harder to grow.)

Even among varieties that are easily available commercially, there can be big differences in sugar content. For an example, see “Nutritionally, Not All Apple Varieties Are Alike.”

People not only should start caring about the sugar in fruit, I think that they will. Right now, the myth is that sugar in fruit is innocent. That is a pleasant illusion that will persist for a while, but is bound to crumple under the weight of its implausibility within a few years. Then interest in low-sugar fruit will pick up.

For annotated links to other posts on diet and health, see:

The Future of Inflation—Ruchir Agarwal and Miles Kimball

Link to the Finance and Development website. Above is a screenshot from April 7, 2022

Ruchir Agarwal and I are pleased to announce our new three-part series on “The Future of Inflation.” Here are permanent links to the three parts:

As a teaser, below and at this link is a table detailing some of the costs and benefits of inflation we address in Part II:

Home Remedies for Allergies

A common treatment for allergies is to go in for periodic shots of the allergen of carefully calibrated size, staying in the waiting area of the doctor’s office for a while after in case there is a reaction.

For some years, I have had a mild allergy to pistachios, pecans and walnuts—mainly a reaction of my tongue. This year I decided to try a home remedy modeled on the more formal periodic shots of allergens often given to deal with more serious allergies. I have been drinking some pistachio milk and pecan milk each day. As near as I could tell from googling around, I think they mostly have separate allergens. (Pecans and walnuts are more similar in their allergens.) So this is too mostly separate home treatments at once. So far, with this experiment just on myself, the results seem good. I have calibrated the dosage to an amount of each that I don’t react to. I soon found that I could drink that amount several times a day and have gradually been able to increase the dose to now half a cup of pistachio milk at a time and 3 tablespoons of pecan milk at a time, but I started at about 2 tablespoons of pistachio milk and 1 tablespoon of pecan milk at a time. I am also now able to tolerate a small spoonful of pistachio butter as an alternative to the half cup of pistachio milk, but that is recent.

Theoretically, I am betting that the my body might tone down reactivity to a type of food that I am exposed to every day in small quantities. It wasn’t guaranteed that would be right, but so far it seems to be working.

Walnut milk also exists. If I am able to conquer pecans, I can go on to treat my walnut allergy with walnut milk. Dealing with my walnut allergy seemed less urgent because I have the workaround of black walnuts. See my post “Hypoallergenic Nuts.” But getting over my walnut allergy would let me eat restaurant dishes that have regular walnuts in them.

Mostly, I want to deal with my allergies to certain nuts because I enjoy nuts. But nuts are generally quite healthy. (See “Our Delusions about 'Healthy' Snacks—Nuts to That!.”) Walnuts in particular have a very positive reputation.

For annotated links to other posts on diet and health, see “Miles Kimball on Diet and Health: A Reader's Guide.”

The Federalist Papers #51 B: The Federal Government Can Restrain Injustices States by Themselves Would Perpetrate

Great Seal of the United States. Link to the Wikipedia article “E pluribus unum”

States can be, as Louis Brandeis said, “laboratories of democracy,” allowing valuable experimentation. On the other side of the ledger, states can perpetrate injustices against groups that don’t have much political power. In the the second half of the Federalist Papers #51, the author (who might be either Alexander Hamilton or James Madison), argues that a coalition to support such an injustice is easier to assemble in a single state that in the entirety of the United States:

… the society itself will be broken into so many parts, interests, and classes of citizens, that the rights of individuals, or of the minority, will be in little danger from interested combinations of the majority. In a free government the security for civil rights must be the same as that for religious rights. It consists in the one case in the multiplicity of interests, and in the other in the multiplicity of sects. The degree of security in both cases will depend on the number of interests and sects; and this may be presumed to depend on the extent of country and number of people comprehended under the same government.

He makes a direct contrast between the danger in a state versus the danger in the United States as a whole of oppression of a group with little political power:

It can be little doubted that if the State of Rhode Island was separated from the Confederacy and left to itself, the insecurity of rights under the popular form of government within such narrow limits would be displayed by such reiterated oppressions of factious majorities that some power altogether independent of the people would soon be called for by the voice of the very factions whose misrule had proved the necessity of it. In the extended republic of the United States, and among the great variety of interests, parties, and sects which it embraces, a coalition of a majority of the whole society could seldom take place on any other principles than those of justice and the general good …

The struggle for Civil Rights in the mid-20th century provides some evidence for the view that the federal government has an important role to play to restrain injustice against those who are disempowered politically.

I love this statement that without justice, a government leaves the situation similar to what would prevail under anarchy or a Hobbesian state of nature:

Justice is the end of government. It is the end of civil society. It ever has been and ever will be pursued until it be obtained, or until liberty be lost in the pursuit. In a society under the forms of which the stronger faction can readily unite and oppress the weaker, anarchy may as truly be said to reign as in a state of nature, where the weaker individual is not secured against the violence of the stronger; and as, in the latter state, even the stronger individuals are prompted, by the uncertainty of their condition, to submit to a government which may protect the weak as well as themselves; so, in the former state, will the more powerful factions or parties be gradnally induced, by a like motive, to wish for a government which will protect all parties, the weaker as well as the more powerful.

Below is the full text of the second half of the Federalist Papers #51:

Second. It is of great importance in a republic not only to guard the society against the oppression of its rulers, but to guard one part of the society against the injustice of the other part. Different interests necessarily exist in different classes of citizens. If a majority be united by a common interest, the rights of the minority will be insecure. There are but two methods of providing against this evil: the one by creating a will in the community independent of the majority that is, of the society itself; the other, by comprehending in the society so many separate descriptions of citizens as will render an unjust combination of a majority of the whole very improbable, if not impracticable. The first method prevails in all governments possessing an hereditary or self-appointed authority. This, at best, is but a precarious security; because a power independent of the society may as well espouse the unjust views of the major, as the rightful interests of the minor party, and may possibly be turned against both parties. The second method will be exemplified in the federal republic of the United States. Whilst all authority in it will be derived from and dependent on the society, the society itself will be broken into so many parts, interests, and classes of citizens, that the rights of individuals, or of the minority, will be in little danger from interested combinations of the majority. In a free government the security for civil rights must be the same as that for religious rights. It consists in the one case in the multiplicity of interests, and in the other in the multiplicity of sects. The degree of security in both cases will depend on the number of interests and sects; and this may be presumed to depend on the extent of country and number of people comprehended under the same government. This view of the subject must particularly recommend a proper federal system to all the sincere and considerate friends of republican government, since it shows that in exact proportion as the territory of the Union may be formed into more circumscribed Confederacies, or States oppressive combinations of a majority will be facilitated: the best security, under the republican forms, for the rights of every class of citizens, will be diminished: and consequently the stability and independence of some member of the government, the only other security, must be proportionately increased. Justice is the end of government. It is the end of civil society. It ever has been and ever will be pursued until it be obtained, or until liberty be lost in the pursuit. In a society under the forms of which the stronger faction can readily unite and oppress the weaker, anarchy may as truly be said to reign as in a state of nature, where the weaker individual is not secured against the violence of the stronger; and as, in the latter state, even the stronger individuals are prompted, by the uncertainty of their condition, to submit to a government which may protect the weak as well as themselves; so, in the former state, will the more powerful factions or parties be gradnally induced, by a like motive, to wish for a government which will protect all parties, the weaker as well as the more powerful. It can be little doubted that if the State of Rhode Island was separated from the Confederacy and left to itself, the insecurity of rights under the popular form of government within such narrow limits would be displayed by such reiterated oppressions of factious majorities that some power altogether independent of the people would soon be called for by the voice of the very factions whose misrule had proved the necessity of it. In the extended republic of the United States, and among the great variety of interests, parties, and sects which it embraces, a coalition of a majority of the whole society could seldom take place on any other principles than those of justice and the general good; whilst there being thus less danger to a minor from the will of a major party, there must be less pretext, also, to provide for the security of the former, by introducing into the government a will not dependent on the latter, or, in other words, a will independent of the society itself. It is no less certain than it is important, notwithstanding the contrary opinions which have been entertained, that the larger the society, provided it lie within a practical sphere, the more duly capable it will be of self-government. And happily for the REPUBLICAN CAUSE, the practicable sphere may be carried to a very great extent, by a judicious modification and mixture of the FEDERAL PRINCIPLE.

PUBLIUS.

Links to my other posts on The Federalist Papers so far:

The Federalist Papers #1: Alexander Hamilton's Plea for Reasoned Debate

The Federalist Papers #3: United, the 13 States are Less Likely to Stumble into War

The Federalist Papers #4 B: National Defense Will Be Stronger if the States are United

The Federalist Papers #5: Unless United, the States Will Be at Each Others' Throats

The Federalist Papers #6 A: Alexander Hamilton on the Many Human Motives for War

The Federalist Papers #11 A: United, the States Can Get a Better Trade Deal—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #12: Union Makes it Much Easier to Get Tariff Revenue—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #13: Alexander Hamilton on Increasing Returns to Scale in National Government

The Federalist Papers #14: A Republic Can Be Geographically Large—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #21 A: Constitutions Need to be Enforced—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #24: The United States Need a Standing Army—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #27: People Will Get Used to the Federal Government—Alexander Hamilton

The Federalist Papers #30: A Robust Power of Taxation is Needed to Make a Nation Powerful

The Federalist Papers #35 A: Alexander Hamilton as an Economist

The Federalist Papers #35 B: Alexander Hamilton on Who Can Represent Whom

The Federalist Papers #36: Alexander Hamilton on Regressive Taxation

The Federalist Papers #39: James Madison Downplays How Radical the Proposed Constitution Is

The Federalist Papers #41: James Madison on Tradeoffs—You Can't Have Everything You Want

The Federalist Papers #42: Every Power of the Federal Government Must Be Justified—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #44: Constitutional Limitations on the Powers of the States—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #45: James Madison Predicts a Small Federal Government

The Federalist Papers #48: Legislatures, Too, Can Become Tyrannical—James Madison

The Federalist Papers #49: Constitutional Conventions Should Be Few and Far Between

The Federalist Papers #50: Periodic Commissions to Judge Constitutionality Won't Work

The Federalist Papers #51 A: Checks and Balance, or ‘Who Guards the Guardians?'