What to Call the Very Rich: Millionaires, Vranaires, Okuaires, Billionaires and Lakhlakhaires

Take a look at this exchange between Elizabeth Warren and Pete Buttigieg in a recent Democratic Primary debate:

“So, the mayor just recently had a fundraiser that was held in a wine cave, full of crystals, and served $900-a-bottle wine,” she said. “Think about who comes to that.”

“We made the decision many years ago that rich people in smoke-filled rooms would not pick the next president of the United States,” she added. “Billionaires in wine caves should not pick the next president of the United States.”

Buttigieg pushed back, noting (as he has before) that he has the smallest net worth of anyone running. “I’m literally the only person on this stage who is not a millionaire or a billionaire,” he said. By Warren’s logic, Buttigieg continued, Warren herself was part of the problem.

“Now, supposing you went home and felt the holiday spirit—I know this isn’t likely, but stay with me—and decided to go on peteforamerica.com and gave the maximum allowable by law, $2,800,” he said. “Would that pollute my campaign because it came from a wealthy person?”

Elizabeth Warren’s is handicapped in this exchange by two facts. First, inflation over the past century makes it so “millionaire” doesn’t mean as much as it once did—and “multimillionaire” could mean someone who has $2 million, which also doesn’t mean as much as it once did. Second, English is missing convenient, noncompound words for many of the relevant powers of ten. If one thinks that while a million dollars makes one rich, that it takes ten million dollars to make someone filthy rich, talking of ten-millionaires not only lacks punch, it is confusing to those who can’t here the different between ten millionaires and ten-millionaires.

Fortunately, Wikipedia provides articles on many of the key powers of ten that detail names for these powers of ten in other languages that can be pressed into service. (These Wikipedia articles also give many fun facts about numbers in between these powers of ten.) Let me give the Wikipedia links and the relevant passages Wikipedia bolding with my own:

In India, Pakistan and South Asia, one hundred thousand is called a lakh, and is written as 1,00,000. The Thai, Lao, Khmer and Vietnamese languages also have separate words for this number: แสน, ແສນ, សែន [saen] and ức respectively. The Malagasy word is hetsy[1].

In South Asia, it is known as the crore.

In Cyrillic numerals, it is known as the vran (вран - raven).

East Asian languages treat 100,000,000 as a counting unit, significant as the square of a myriad, also a counting unit. In Chinese, Korean, and Japanese respectively it is (simplified Chinese: 亿; traditional Chinese: 億; pinyin: yì) (or Chinese: 萬萬; pinyin: wànwàn in ancient texts), eok (억/億) and oku (億). These languages do not have single words for a thousand to the second, third, fifth power, etc.

(“Million, “billion” and “trillion” are perfectly good words, and in recent years the British usage for “billion” and “trillion” have begun converging toward the American usage. For 10,000, I have always liked the word “myriad.”)

Making some editorial choices, let me then propose the following names, including the traditional ones:

$1,000,000: millionaire

$10,000,000: vranaire

$100,000,000: okuaire

$1,000,000,000: billionaire

$10,000,000,000: lakhlakhaire

$100,000,000,000: hundred-billionaire

$1,000,000,000,000: trillionaire

Notes on roads taken and not taken:

“croraire” would be hard to pronounce; hence I prefer “vranaire.”

I have spent a lot of time in Japan, so I am drawn to the Japanese word for 100,000,000.

Wikipedia gives no single noncompound word for 10,000,000,000. But using “lakh,” it is possible to make a compound term that is only two syllables and is quite distinctive and memorable. (10,000,000,000 = 100,000 x 100,000. Here is a link for the pronunciation of lakh.

I am at a loss to find a noncompound word for 100,000,000,000, but at least “hundred-billionaires” is distinguishable in speech from “one hundred billionaires.”

If you want to know what these various categories of rich folks are like, I highly recommend the book Richistan, by Robert Frank, about what it is like to be very rich. It makes a difference which power of ten one has exceeded! It is very, very different to be an okuaire than to be a vranaire. A vranaire has enough to retire early in comfort and have a nice house in any city, but having almost anything one selfishly desires that money can buy requires being at least an okuaire. And it is not hard to have philanthropic desires or desires for power to affect human history that would easily require being a billionaire or lakhlakhaire.

As for millionaires, a tenured economics professor who has been required by their college or university to save 15% of their salary for retirement should at a certain age be a millionaire on paper unless they have had bad luck.

Related post: New Words for a New Year

Christmas as a Clue to What People Want

In “An Agnostic Grace,” I write:

And we remember Jesus Christ, symbol of all that is good in humankind, and thereby clue to the God or Gods Who May Be.

Christmas, the celebration of Jesus’s birth, is a clue to men’s and women’s desiring. People want:

many, many things that money can buy, as the commercial aspect of Christmas attests;

the thrill of discovery, as the idea of gifts as surprises attests;

good food, as the culinary aspect of Christmas attests;

close, warm relationships with family and friends, as Christmas gatherings with family and friends attest;

not feeling bad about themselves, as the idea that Jesus came to bring forgiveness of sins attests;

not having death undo us all, as the idea that Jesus came to bring victory over death attests.

May we, in this Christmas season, get much of what we want now, and let us make great plans to get more of what we want later.

Don’t miss other Christmas posts:

That Baby Born in Bethlehem Should Inspire Society to Keep Redeeming Itself

An Optical Illusion: Nativity Scene or Two T-Rex's Fighting over a Table Saw?

Also see “The Book of Uncommon Prayer” and my happiness sub-blog.

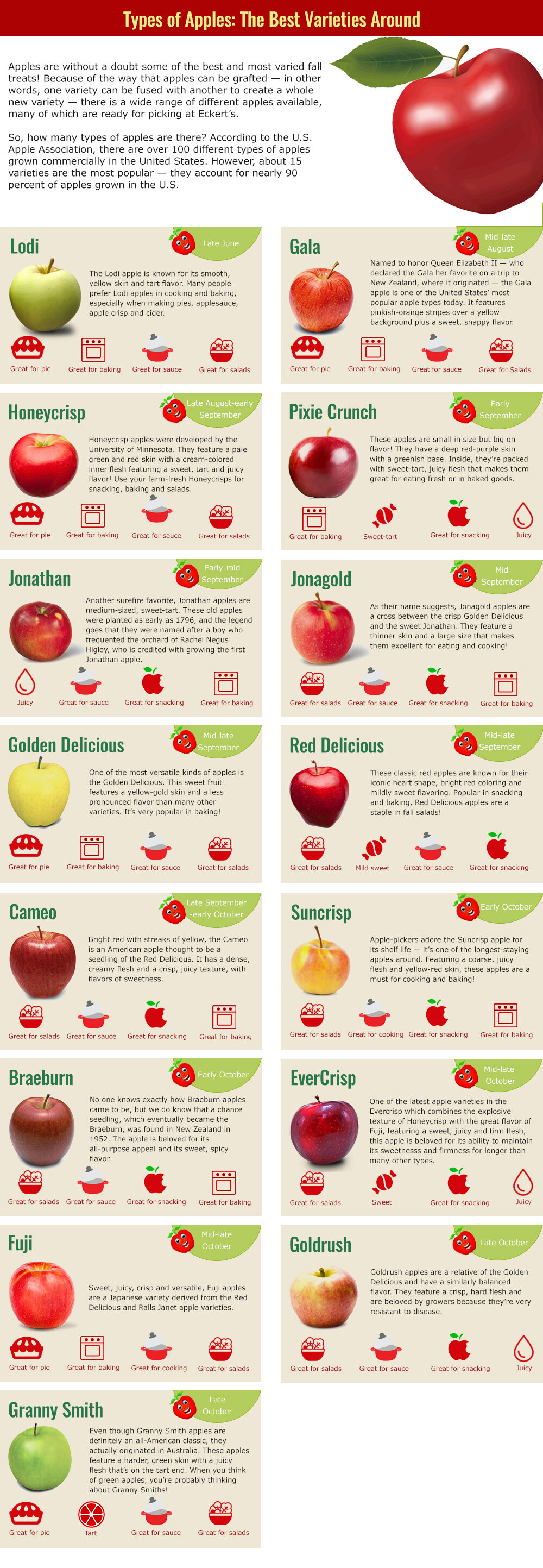

Nutritionally, Not All Apple Varieties Are Alike

Whole fruits have valuable nutrients and fiber. But they also have a lot of sugar. That means that, in many ways, fruit is both good and bad—an issue I discuss in the section “The Conundrum of Fruit” of my post "Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid.” But wouldn’t it be possible to breed fruit that had less sugar but continued to have all the other nutritionally valuable elements? The answer is definitely yes, and it may be easier than you think. Heirloom varieties and other older varieties are a promising place to look for less sugary varieties of fruit. Humans have spent hundreds of years breeding fruit that has more sugar and is therefore sweeter.

Even now, saying a variety of fruit was sweeter would probably be good marketing, so the artificial selection pressures are probably mostly in the direction of sweeter and therefore more sugary fruit. But if a large subset of consumers wanted low-sugar fruit, it wouldn’t be long before the market provided low-sugar fruit from some combination of heirloom varieties and newly bred low-sugar varieties of fruit.

As things stand, the demand for low-sugar fruit is too low for fruit to be marketed that way. But different varieties from the same species of fruit do have different levels of sugar. The table below, from “Fructose in different apple varieties,” by Katharina Hermann and Ursula Bordewick-Dell is a nice example:

A Granny Smith apple has less than a third the sugar of a Fuji apple, however you slice it!

Currently, in our culture, fruits have a very good reputation. But the situation is much more complicated than that. Fruit juice has much less of the good and all the bad of the sugar. And even among whole fruits, some are much healthier than others. Sugar doesn’t suddenly become innocent simply because it is inside fruit. It is a matter of whether, given the amount of sugar in a particular variety of fruit the good of the other nutrients can outweigh the bad of the sugar. And that in turn depends a lot on how much sugar there is.

I hope that farmers who have an interest in fostering health will take an interest in identifying, developing and marketing low-sugar varieties of fruit. I am happy to feature low-sugar varieties of fruit on this blog if you let me know about them.

For annotated links to other posts on diet and health, see:

Christof Koch: Will Machines Ever Become Conscious?

Link to “Will Machines Ever Become Conscious”

In his Scientific American article “Will Machines Ever Become Conscious?” Christof Koch questions whether a brain emulation would be truly conscious:

Let us assume that in the future it will be possible to scan an entire human brain, with its roughly 100 billion neurons and quadrillion synapses, at the ultrastructural level after its owner has died and then simulate the organ on some advanced computer, maybe a quantum machine. If the model is faithful enough, this simulation will wake up and behave like a digital simulacrum of the deceased person—speaking and accessing his or her memories, cravings, fears and other traits.

If mimicking the functionality of the brain is all that is needed to create consciousness, as postulated by GNW theory, the simulated person will be conscious, reincarnated inside a computer. Indeed, uploading the connectome to the cloud so people can live on in the digital afterlife is a common science-fiction trope.

IIT posits a radically different interpretation of this situation: the simulacrum will feel as much as the software running on a fancy Japanese toilet—nothing. It will act like a person but without any innate feelings, a zombie (but without any desire to eat human flesh)—the ultimate deepfake.

To create consciousness, the intrinsic causal powers of the brain are needed. And those powers cannot be simulated but must be part and parcel of the physics of the underlying mechanism.

He seems to have written an entire book on this theme: The Feeling of Life Itself: Why Consciousness Is Widespread but Can't Be Computed. However, my comments here are only on the Scientific American article, not the book (which I haven’t read).

Christof bases his skepticism that a brain emulation would be truly conscious on Integrated Information Theory. He writes:

Giulio Tononi, a psychiatrist and neuroscientist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, is the chief architect of IIT, with others, myself included, contributing. The theory starts with experience and proceeds from there to the activation of synaptic circuits that determine the “feeling” of this experience. Integrated information is a mathematical measure quantifying how much “intrinsic causal power” some mechanism possesses. Neurons firing action potentials that affect the downstream cells they are wired to (via synapses) are one type of mechanism, as are electronic circuits, made of transistors, capacitances, resistances and wires.

But when I read the Wikipedia article “Integrated information theory,” it seems like a synapse by synapse simulation of a human brain would satisfy perfectly well all of the claimed requirements of consciousness. Take a look for yourself and see what you think.

I am totally willing to concede that general artificial intelligence, built on other principles than copying the workings of the human brain, might or might not be conscious, depending on the particular design.

Christof seems to get awfully close to agreeing with me about the consciousness of very, very detailed brain emulations that required copying from a particular individual when he writes:

In principle, however, it would be possible to achieve human-level consciousness by going beyond a simulation to build so-called neuromorphic hardware, based on an architecture built in the image of the nervous system.

I don’t see why a detailed logical image of the nervous system can’t do just as much. After all, things can’t be computed in electronic computers without one electron causally affecting another at every step. So there is causal power there. In any case, in his Scientific American article, Christof has failed to make clear how a very, very, very detailed synapse by synapse brain emulation is different from “neuromorphic hardware” in terms of causal powers. Computer programs have “intrinsic causal power” too.

Update, December 22, 2019: Robin Hanson comments on Twitter:

"But [by] 'Integrated information theory,' it seems like a synapse by synapse simulation of a human brain would satisfy perfectly well all of the claimed requirements of consciousness." Yes, that's completely obvious. Quite crazy to think otherwise.

Related Posts:

On Habit Formation

Habit formation is a staple of macroeconomics, finance, and behavioral economics, and deserves to be taken seriously in thinking about tax policy. My star student Jiannan Zhou has nailed down the parameters of habit formation preferences using a hypothetical choice survey that he designed and fielded on MTurk and analyzed using the computational power of Hamiltonian Markov Chain Monte Carlo. (It will be straightforward to collect another round of data on a more representative survey such as Arie Kapteyn’s Understanding America Survey—a web survey that will accept any serious scientific survey question given the requisite funding.)

In words drawn straight from his paper “Survey Evidence on Habit Formation,” here is what Jiannan finds:

Habit formation exists, as a phenomenon distinct from adjustment and cognition costs.

Habit depreciates by about two thirds per year.

Neither additive nor multiplicative habit is consistent with people’s behavior. Almost all current habit formation models in the literature assume either one of these two habit utility functions …

The effect of habit formation on utility is about as strong as that of keeping-up-with-the-Joneses.

Habit formation combined with keeping-up-with-the-Joneses could generate the income-happiness pattern of the Easterlin paradox.

Jiannan is also able to distinguish between internal habit formation (one’s own past consumption as a reference point) and external habit formation (other people’s past consumption as a reference point). Both internal and external habits exist, with external habits accounting for about 17% of habit.

Jiannan has a high-level of statistical precision even with a modest sample size because the hypothetical choices can be—and are—designed to reveal a lot about people’s preferences.

The Easterlin paradox is the puzzle that happiness and life satisfaction often seem nearly flat over time even when per capita income is dramatically increasing. (There are strong versions of this claim that are questionable empirically, but there is little dispute that the rate at which happiness and life satisfaction go up with income is surprisingly low—low enough that dividing by these income coefficients in a regression yields surprisingly high—and potentially suspect—estimates of willingness to pay.)

Jiannan may undersell his result about the strength of habit formation plus keeping-up-with-the-Jones by tying it to the Easterlin paradox. The Easterlin paradox is a “paradox” in part due to a crucial assumption that happiness as measured on surveys is the same thing as utility (plus noise). Bob Willis and I question that assumption in our paper “Utility and Happiness.” Jiannan’s result is clearly about revealed-preference utility as long as one is willing to consider hypothetical choices as revealing preferences. What Jiannan has found is that people state strongly that their future experience would be better if other people’s current and past consumption were lower or if their own past consumption were lower.

Here is an example of the kind of survey questions Jiannan uses:

The strong dependence of people’s stated preferences on their situation relative to other people and relative to their own past gives me pause. Some might think that means it is difficult to make everyone better off. But—optimist that I am—I like to think it points to the importance people place on respect, dignity and being “part of the club,” and that it is possible to design society so there is more of these social goods for everyone. As it is, those things come mainly to people who are high up on the ladder. But what if he could have the kind of world where everyone who keeps the most basic necessary rules of society gets respect and dignity and full belonging?

Jiannan is on the job market right now. Anyone who doesn’t have him on their interview list should. And even those not searching to hire should read his paper if they have any interest in macro, finance, behavioral economics or tax policy. Here is the link to his website. And here is the current version of his presentation slides for his habit formation paper.

Don’t miss this post about the academic work of my most famous student, Noah Smith:

See links to some of my other papers on happiness here:

Postscript: Jiannan is the first student for whom I have been the main advisor since I moved to the University of Colorado Boulder. See “Miles Moves to the University of Colorado Boulder.”

Does Reducing Saturated Fat Reduce Cardiovascular Disease?

An important part of the conventional wisdom on diet and health is that saturated fats are bad. The basic idea is that saturated fats raise blood cholesterol and thereby clog arteries, which can lead to heart attacks and strokes, among other bad events.

The article shown above, “Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease,” by Lee Hooper, Nicole martin, Asmaa Abdelhamid and George Davey Smith, is a meta-analysis of 15 randomized clinical trials that meet criteria for being fairly solid evidence. They show convincingly that whatever it is that happens when people are advised to reduce saturated fat intake by a dietition, nutritionist or nurse is helpful in reducing bad cardiovascular events—perhaps by around 10% to 15% if one had to guess (though substantially smaller or bigger effects are within the confidence intervals).

The idea in most of these randomized trials was to get people to substitute polyunsatured or monounsatured fats for saturated fats that were cut out. Sometimes the experimental subjects were given polyunsaturated or monounsatured fats to eat. The big blind spot in the studies underlying this meta-analysis is that they don’t seem to distinguish between cutting out animal protein and cutting out saturated fat. To see if it is cutting out animal protein that is beneficial rather than saturated fat per se, it would be helpful to have an experiment in which experimental subjects were encouraged to cut out meat and dairy but increase plant-based saturated fat—by consuming more coconut milk, for example.

Alternatively, trials that compare drinking skim milk to whole milk or compare eating lean meat to eating full-fat meat from the same animal would hold the amount and type of animal protein reasonably constant while reducing saturated fat. (One might also want to increase the amount of polyunsaturated fat or monounsatured fat to keep total amount of fat constant.) Googling “randomized trial skim milk whole milk” I didn’t find much other than this very small study of 18 people which claims that the previous evidence was unclear about skim milk vs. whole milk and found little effect itself:

Why is it important to control for animal protein? First of all, a large share of the milk people drink contains A1 casein. See “Exorcising the Devil in the Milk.” If nutritional advice to avoid saturated fats causes some people to avoid milk rather than switch to skim milk (perhaps because they hate the taste of skim milk), it would protect them from A1 milk protein. (Another way to avoid A1 casein is to buy A2 Milk.) Second, at least some types of animal protein stimulates insulin production in the body. See “Forget Calorie Counting; It's the Insulin Index, Stupid” and “Why a Low-Insulin-Index Diet Isn't Exactly a 'Lowcarb' Diet.”

The idea that animal products are bad because of saturated fat has often caused evidence that consuming too much in the way of animal products has health risks to be interpreted as evidence that saturated fat is bad. This idea is encouraged by the fact that saturated fat does seem to make blood cholesterol look worse by the standards of the conventional wisdom about blood cholesterol. But the conventional wisdom is based on blood lipid measurements on only three dimensions of what is probably more like a ten-dimensional vector of important subspecies of cholesterol bearing objects. See “What is the Evidence on Dietary Fat?” (On the subject here, another relevant post is “How Unhealthy are Red and Processed Meat?”)

The bottom line is that a lot of research remains to be done. Way too little research has been done to answer the questions that a skeptic of the dangers of saturated fat would pose. Saturated fat may be terrible. But despite the conventional wisdom, we really don’t know for sure yet.

It matters to get things right. My view is that the health would improve markedly if it became conventional wisdom that dietary sugar is much, much more harmful than dietary fat (even with no particular mention of the different kinds of dietary fat other than transfats being bad). As it is, an anti-dietary-fat message is crowding out the clear anti-sugar message that I think is much more on target and much more important. (The study discussed in “Why a Low-Insulin-Index Diet Isn't Exactly a 'Lowcarb' Diet” for example, should make one quite worried about sugar consumption and processed food consumption—which currently are reasonably close to being the same thing, since almost all highly processed food contains a fair amount of sugar.)

For annotated links to other posts on diet and health, see:

The Federalist Papers #3: United, the 13 States are Less Likely to Stumble into War

Reading what John Jay (writing as Publius) writes in The Federalist Papers #3 the national security advantages of having the 13 states united rather than divided, I expected his first argument to be the greater military and economic power of a larger nation. But he actually leads with the reasons that united, the 13 states are less likely to cause a war. This paragraph is the heart of The Federalist Papers #3:

The number of wars which have happened or will happen in the world will always be found to be in proportion to the number and weight of the causes, whether REAL or PRETENDED, which PROVOKE or INVITE them. If this remark be just, it becomes useful to inquire whether so many JUST causes of war are likely to be given by UNITED AMERICA as by DISUNITED America; for if it should turn out that United America will probably give the fewest, then it will follow that in this respect the Union tends most to preserve the people in a state of peace with other nations.

John Jay argues that united, the 13 states are less likely to cause a war for these reasons:

Leaders drawn from the whole nation are likely to be more competent than leaders drawn from only a part.

United, the 13 states will have a more consistent foreign policy.

Because commercial and other interests differ from state to state, politicians of one or a few states face greater temptations to offend foreign nations than national politicians.

Because commercial and other interests differ from state to state, voters of one or a few states face greater temptations to vote for things that will offend foreign nations than voters of the nation as a whole.

One or a few states on their own are more likely to start a war by direct military action than the national government.

Historically, most wars with Native Americans have been caused by one state or by people from one state.

Border states face extra temptation to military action across that border.

One state or a weak confederacy is likely to face stronger retaliation than the United States.

This last sub-bullet does refer to the greater military and economic power of a larger nation, but it is still in the context of the states being less likely to stumble into a war they caused if they are united.

Now, let me map all of this to the full text of The Federalist Papers #3. First, here is the title and the leadup to the paragraph I noted above was at the heart of this number:

United, the 13 States are Less Likely to Stumble into War

The Same Subject Continued: Concerning Dangers From Foreign Force and Influence

For the Independent Journal.

Author: John Jay

To the People of the State of New York:

IT IS not a new observation that the people of any country (if, like the Americans, intelligent and wellinformed) seldom adopt and steadily persevere for many years in an erroneous opinion respecting their interests. That consideration naturally tends to create great respect for the high opinion which the people of America have so long and uniformly entertained of the importance of their continuing firmly united under one federal government, vested with sufficient powers for all general and national purposes.

The more attentively I consider and investigate the reasons which appear to have given birth to this opinion, the more I become convinced that they are cogent and conclusive.

Among the many objects to which a wise and free people find it necessary to direct their attention, that of providing for their SAFETY seems to be the first. The SAFETY of the people doubtless has relation to a great variety of circumstances and considerations, and consequently affords great latitude to those who wish to define it precisely and comprehensively.

At present I mean only to consider it as it respects security for the preservation of peace and tranquillity, as well as against dangers from FOREIGN ARMS AND INFLUENCE, as from dangers of the LIKE KIND arising from domestic causes. As the former of these comes first in order, it is proper it should be the first discussed. Let us therefore proceed to examine whether the people are not right in their opinion that a cordial Union, under an efficient national government, affords them the best security that can be devised against HOSTILITIES from abroad.

The number of wars which have happened or will happen in the world will always be found to be in proportion to the number and weight of the causes, whether REAL or PRETENDED, which PROVOKE or INVITE them. If this remark be just, it becomes useful to inquire whether so many JUST causes of war are likely to be given by UNITED AMERICA as by DISUNITED America; for if it should turn out that United America will probably give the fewest, then it will follow that in this respect the Union tends most to preserve the people in a state of peace with other nations.

My first 4 points above all have to do with treaty violations, which is where John Jay goes first:

The JUST causes of war, for the most part, arise either from violation of treaties or from direct violence. America has already formed treaties with no less than six foreign nations, and all of them, except Prussia, are maritime, and therefore able to annoy and injure us. She has also extensive commerce with Portugal, Spain, and Britain, and, with respect to the two latter, has, in addition, the circumstance of neighborhood to attend to.

It is of high importance to the peace of America that she observe the laws of nations towards all these powers, and to me it appears evident that this will be more perfectly and punctually done by one national government than it could be either by thirteen separate States or by three or four distinct confederacies.

Now, here are the paragraphs giving the key arguments, headed by my statement of each argument:

1. Leaders drawn from the whole nation are likely to be more competent than leaders drawn from only a part.

Because when once an efficient national government is established, the best men in the country will not only consent to serve, but also will generally be appointed to manage it; for, although town or country, or other contracted influence, may place men in State assemblies, or senates, or courts of justice, or executive departments, yet more general and extensive reputation for talents and other qualifications will be necessary to recommend men to offices under the national government,--especially as it will have the widest field for choice, and never experience that want of proper persons which is not uncommon in some of the States. Hence, it will result that the administration, the political counsels, and the judicial decisions of the national government will be more wise, systematical, and judicious than those of individual States, and consequently more satisfactory with respect to other nations, as well as more SAFE with respect to us.

2. United, the 13 states will have a more consistent foreign policy.

Because, under the national government, treaties and articles of treaties, as well as the laws of nations, will always be expounded in one sense and executed in the same manner,--whereas, adjudications on the same points and questions, in thirteen States, or in three or four confederacies, will not always accord or be consistent; and that, as well from the variety of independent courts and judges appointed by different and independent governments, as from the different local laws and interests which may affect and influence them. The wisdom of the convention, in committing such questions to the jurisdiction and judgment of courts appointed by and responsible only to one national government, cannot be too much commended.

3. Because commercial and other interests differ from state to state, politicians of one or a few states face greater temptations to offend foreign nations than national politicians.

Because the prospect of present loss or advantage may often tempt the governing party in one or two States to swerve from good faith and justice; but those temptations, not reaching the other States, and consequently having little or no influence on the national government, the temptation will be fruitless, and good faith and justice be preserved. The case of the treaty of peace with Britain adds great weight to this reasoning.

4. Because commercial and other interests differ from state to state, voters of one or a few states face greater temptations to vote for things that will offend foreign nations than voters of the nation as a whole.

Because, even if the governing party in a State should be disposed to resist such temptations, yet as such temptations may, and commonly do, result from circumstances peculiar to the State, and may affect a great number of the inhabitants, the governing party may not always be able, if willing, to prevent the injustice meditated, or to punish the aggressors. But the national government, not being affected by those local circumstances, will neither be induced to commit the wrong themselves, nor want power or inclination to prevent or punish its commission by others.

So far, therefore, as either designed or accidental violations of treaties and the laws of nations afford JUST causes of war, they are less to be apprehended under one general government than under several lesser ones, and in that respect the former most favors the SAFETY of the people.

Next, John Jay turns to violence instigated by one of the states, using three arguments to say that divided states will get in more trouble.

5. One or a few states on their own are more likely to start a war by direct military action than the national government.

As to those just causes of war which proceed from direct and unlawful violence, it appears equally clear to me that one good national government affords vastly more security against dangers of that sort than can be derived from any other quarter.

Historically, most wars with Native Americans have been caused by one state or by people from one state.

Because such violences are more frequently caused by the passions and interests of a part than of the whole; of one or two States than of the Union. Not a single Indian war has yet been occasioned by aggressions of the present federal government, feeble as it is; but there are several instances of Indian hostilities having been provoked by the improper conduct of individual States, who, either unable or unwilling to restrain or punish offenses, have given occasion to the slaughter of many innocent inhabitants.

Border states face extra temptation to military action across that border.

The neighborhood of Spanish and British territories, bordering on some States and not on others, naturally confines the causes of quarrel more immediately to the borderers. The bordering States, if any, will be those who, under the impulse of sudden irritation, and a quick sense of apparent interest or injury, will be most likely, by direct violence, to excite war with these nations; and nothing can so effectually obviate that danger as a national government, whose wisdom and prudence will not be diminished by the passions which actuate the parties immediately interested.

One state or a weak confederacy is likely to face stronger retaliation than the United States.

But not only fewer just causes of war will be given by the national government, but it will also be more in their power to accommodate and settle them amicably. They will be more temperate and cool, and in that respect, as well as in others, will be more in capacity to act advisedly than the offending State. The pride of states, as well as of men, naturally disposes them to justify all their actions, and opposes their acknowledging, correcting, or repairing their errors and offenses. The national government, in such cases, will not be affected by this pride, but will proceed with moderation and candor to consider and decide on the means most proper to extricate them from the difficulties which threaten them.

Besides, it is well known that acknowledgments, explanations, and compensations are often accepted as satisfactory from a strong united nation, which would be rejected as unsatisfactory if offered by a State or confederacy of little consideration or power.

In the year 1685, the state of Genoa having offended Louis XIV., endeavored to appease him. He demanded that they should send their Doge, or chief magistrate, accompanied by four of their senators, to FRANCE, to ask his pardon and receive his terms. They were obliged to submit to it for the sake of peace. Would he on any occasion either have demanded or have received the like humiliation from Spain, or Britain, or any other POWERFUL nation?

In Honor of Marvin Goodfriend

Two monetary policy experts died this past week. I can depend on others to properly honor Paul Volcker (September 5, 1927 – December 8, 2019), who used dramatically high interest rates to bring down inflation in the 70s. But Marvin Goodfriend (November 6, 1950 – December 5, 2019) is in danger of being underappreciated. Despite being in many ways a monetary policy hawk, Marvin helped lay out the path to dramatically low interest rates to avoid a repeat of the Great Recession or worse. (Worse might go by the name of “The Great Deflation” or “Secular Stagnation.”)

In a November 2000 Journal of Money, Credit and Banking article, Marvin suggested a modern way to impose a carry tax on paper currency. (See “Marvin Goodfriend on Electronic Money.”) Even more significantly, in a 2016 Jackson Hole paper, Marvin pointed out how a floating exchange rate between paper dollars and dollars in the bank could totally remove any lower bound on interest rates. He framed this in the context of all the interest rate taboos that have been left behind in the past. I was there that year at Jackson Hole. In the comment period, I contrasted this to my preferred approach of a tightly controlled crawling-peg exchange rate between paper dollars and dollars in the bank. (See “Some Selections Related to Negative Interest Rate Policy from the General Discussions at the 2016 Jackson Hole Symposium on ‘Designing Resilient Monetary Policy Frameworks for the Future.’”) Marvin simply said:

On Miles Kimball’s point, you know Miles and I are allies on this, and I’d like to talk to him about the crawling peg and the feasibility. Maybe I’m wrong, I don’t know. But basically we’re in the same camp as this is something that should happen and can happen.

I am proud to be called an ally of Marvin Goodfriend on this.

I arranged a call with Marvin a couple of weeks later to talk about the difference between our two approaches. He said that he thought deep negative rates would be resisted so long that by the time a central bank was ready, it would have already destroyed most of its credibility. If so, then a crawling peg exchange rate between paper currency and money in the bank might not be fully credible, but a floating rate between paper currency and money in the bank could be. I still don’t think Marvin is right about the best course of action, and I think he overestimates the difficulty of credibility for a crawling peg exchange rate, but his perspective is a very interesting one. Most importantly, his plan, like mine, would work. A floating exchange rate between paper currency and money in the bank would remove any lower bound on nominal interest rates and allow a robust monetary policy response to any decline in aggregate demand.

In the future, I predict that negative rates—even deep negative rates—will be seen as a normal and essential part of monetary policy. In that future, Marvin will be seen as an important part of the history of negative interest rate policy.

Other posts on Marvin Goodfriend and Paul Volcker:

For other posts on negative interest rate policy, see “How and Why to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound: A Reader’s Guide.”

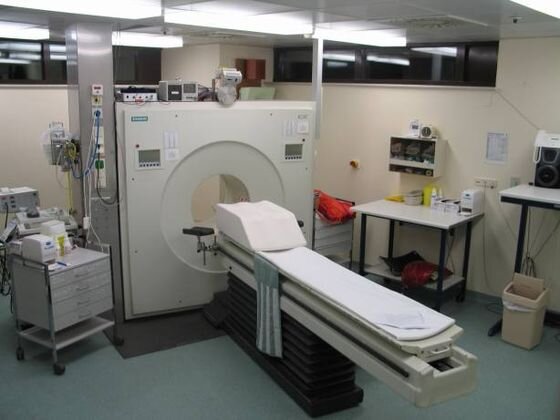

Cancer Cells Love Sugar; That’s How PET Scans for Cancer Work

Last week, a friend who is a cancer survivor noted that people are given radioactive sugar before a positron emission tomography (PET) scan. Why does this work? It is because cancer cells love sugar. Here is how “Oncology” section of the current version of the Wikipedia article on “Positron emission tomography” says it (glucose is blood sugar):

PET scanning with the tracer fluorine-18 (18F) fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), called FDG-PET, is widely used in clinical oncology. This tracer is a glucose analog that is taken up by glucose-using cells and phosphorylated by hexokinase (whose mitochondrial form is greatly elevated in rapidly growing malignant tumors). … FDG is trapped in any cell that takes it up until it decays, since phosphorylated sugars, due to their ionic charge, cannot exit from the cell. This results in intense radiolabeling of tissues with high glucose uptake, such as the normal brain, liver, kidneys, and most cancers. As a result, FDG-PET can be used for diagnosis, staging, and monitoring treatment of cancers, particularly in Hodgkin's lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and lung cancer.

I have a simple piece of advice: Don’t give cancer cells too much of what they love. And anyone can have cancer cells without knowing it. Just because they aren’t making obvious trouble yet doesn’t mean they won’t. If you don’t feed them lavishly, they are less likely to grow and multiply.

For annotated links to other posts on diet and health, see: