Link to Judy Shelton’s October 11, 2016 Wall Street Journal op-ed “A Trans-Atlantic Revolt Against Central BankersConservative leaders in the U.S. and Britain are standing up for those left behind by ultralow rates.”

In an October 11, 2016 Wall Street Journal op-ed, Judy Shelton manages to be wrong on many counts about monetary policy, but wrong in an instructive way. Let me answer her points.

First, Judy does helpfully quote Maury Obstfeld and Christine Lagarde–both of whom are exactly right. Maury points out the political consequences insufficiently stimulative monetary policy among other economic problems:

… as IMF chief economist Maurice Obstfeld recently told the press, the problem has to do with the political consequences of sluggish economic performance. “In short, growth has been too low for too long,” he said, “and in many countries its benefits have reached too few, with political repercussions that are likely to depress global growth further.”

Christine Lagarde is exactly right in pointing out the monetary policy can do more. In particular, negative interest rate policy is still in its infancy, and could go a lot further:

In a Sept. 28 speech at Northwestern University, IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde dismissed as “pessimists” those who think central banks are not stimulating economic growth. “In my view, there is more policy space—more room to act—than is commonly believed,” she declared. “Monetary policy in advanced economies needs to remain expansive at this stage.”

Having just returned from visiting the Bank of Japan (where I communicated the message of my advice in “The Bank of Japan Renews Its Commitment to Do Whatever it Takes” with this Powerpoint file–pdf download), the Bank of Thailand, Bank Indonesia and the Bank of Korea in the past two weeks, I am headed at the beginning of next month on a tour of European central banks to try to expand the set of options European central banks are actively thinking about. Copying over from the cumulative itinerary I keep updating in my post “Electronic Money: The Powerpoint File”:

- Sveriges Riksbank (Stockholm), October 31-November 1, 2016

- Austrian National Bank November 2-4, 2016

- Bank of Israel, November 7-8, 2016

- Brussels Conference on “What is the impact of negative interest rates on Europe’s financial system? How do we get back?” sponsored by the European Capital Markets and Institute (ECMI), the Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) and the Brevan Howard Centre for Financial Analysis, November 9, 2016

- Czech National Bank, November 10-11, 2016

- European Central Bank, November 14-16, 2016

- Bank of International Settlements, November 17, 2016

- Swiss National Bank, November 18

1. Besides rejecting Maury’s and Christine’s sage words, Judy’s first mistake is to assume, that low interest rates exacerbate inequality. Judy writes:

The monetary policies enacted by the world’s leading central banks are a predominant mechanism for doling out differential financial rewards—exacerbating income inequality in the process. The Federal Reserve’s ultralow interest rates, intended to stimulate economic growth, have flooded wealthy investors and corporate borrowers with cheap money, while savers with ordinary bank accounts have been obliged to accept next-to-nothing returns.

Judy does have company in this mistake:

British Prime Minister Theresa May took on her own nation’s central bank in an Oct. 5 speech at her Conservative Party’s annual conference. “People with assets have got richer,” she said. “People without them have suffered. People with mortgages have found their debts cheaper. People with savings have found themselves poorer.”

The problem with this view is that there is strong, mechanical tendency for those who are lending to have a higher net worth than those who are borrowing. Thus, if low interest rates hurt lenders and help borrowers, it seems much more likely that this reduces inequality. And many of those who are wealthy and yet are borrowing in a big way are the entrepreneurs and firms investing in factories, software and R&D that are so important to the progress of an economy. And many firms borrow with long-term corporate bonds that commit to levels of coupon payments that don’t immediately change with fluctuations in short-term interest rates. It is true that lucky homeowners contribute a great deal to inequality, but leaving aside the travesty of the Great Inflation of the 1970′s, this has had at least as much to do with capital gains in markets where construction is overly restricted as to interest rate fluctuations.

2. Donald Trump is a little more on target in identifying those hurt by low rates–not those who are especially poor, but those who have been big savers who don’t like risk:

Mr. Trump readily admits that, as a developer, he likes low interest rates; at the same time, he recognizes that others have been penalized by the Fed’s monetary-policy decisions. As he said in a Sept. 12 CNBC interview: “The people that were hurt the worst are people that saved their money all their lives and thought they would live off their interest, and those people are getting just absolutely creamed.”

But this statement is still wrong, because it overestimates the power of the Fed and other central banks. In particular, the idea that central banks can initiate higher rates and keep them permanently higher is a myth exaggerating the power of central banks. In “Mark Carney: Central Banks are Being Forced Into Low Interest Rates by the Supply Side Situation” I talk about Bank of England chief Mark Carney’s eloquent explanation of how central banks must take as given what the natural rate of interest is. If they keep interest rates higher than that natural rate, it will hurt an economy badly, which will probably require lower rates to fix. Mario Draghi said something similar and similarly true, as I lay out in “Mario Draghi Reminds Everyone that Central Banks Do Not Determine the Medium-Run Natural Interest Rate.”

Central bankers are just making false excuses if they ever say they can’t stimulate more. But in the current environment, it is the truth when they say that the natural rate is low enough that they can’t stimulate effectively without having shockingly low rates.

Somewhat paradoxically, the only time central banks are to blame for persistently low rates is if they have previously failed to make rates low enough. Because the Fed did not have a -6% rate back in 2009 as the Taylor rule would have recommended, the Great Recession dragged on, and zero rates persisted for seven years, 2009–2015, with very low rates in 2016 as well. Moreover, because no central bank in modern times has yet demonstrated a willingness to use deep negative rates, or to have even a small nonzero paper currency interest rate, the markets factor in the chance of a continuing slump up against a lower bound on interest rates. Demonstrating clearly that central banks have and are potentially willing to use much, much more ammunition if needed would do a lot to allay this fear and thereby possibly bring up long-term rates.

3. It is interesting judging Judy’s statement that

… unconventional monetary policy has failed to deliver the anticipated boost to growth.

I suspect that, whatever the brave face they put on in public in order to maximize positive expectations, central bankers were always quite uncertain about how big the effect of quantitative easing would be. Since the simplest optimizing theories say that quantitative easing has no stimulative effect at all, the actual effect of quantitative easing was always going to depend on mechanisms that were not well understood. So anyone sensible would have had a large standard error on their estimate of the likely effective of quantitative easing. And similarly, there is reason for a large standard error on any estimate of the undesirable side effects of quantitative easing–particularly at dosages that higher than those that have been used so far.

By contrast, simple theories say that negative real rates should have essentially the same effect regardless of whether they come from high rates of inflation or from nominal rates. So “anticipated boost to growth” is a much more tightly defined phrase in relation to negative interest rates. But we know that responding to a recession historically requires something like a 5 or 6 percentage point reduction in short-term interest rates to get historical norms of recovery speed. And presumably a major financial crisis like that toward the end of 2008, after having been allowed to fester, could easily require a bigger reduction in rates to offset by monetary policy.

Given the moderate negative rates so far, relatively well-established numbers for the effect of interest rate cuts would not suggest any bigger an impact than we have seen from negative rates. And as I point out in “If a Central Bank Cuts All of Its Interest Rates, Including the Paper Currency Interest Rate, Negative Interest Rates are a Much Fiercer Animal,” historical norms of the effect of interest rate cuts apply, strictly speaking, only when the paper currency interest rate is kept in line or below other interest rates.

4. Judy’s assertion

… the Fed’s large-scale interventions in credit and investment markets have created significant distortions that threaten financial stability. We can’t expect Main Street to passively absorb the costs of a future Wall Street bailout; there is a limit to public patience with monetary policy that not only smacks of favoritism but might also be causing more harm than good.

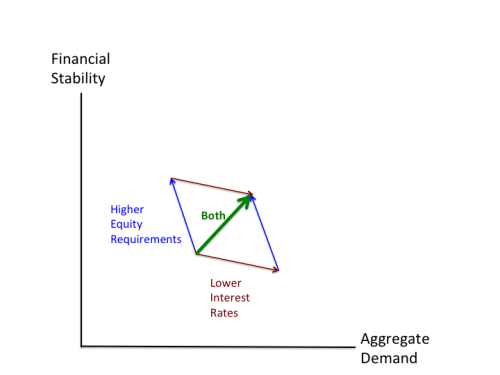

understates the power of high capital requirements and low leverage limits to stabilize the financial markets once negative interest rate policy frees one from worrying about insufficient aggregate demand. Let me reproduce here my diagram from “Why Financial Stability Concerns Are Not a Reason to Shy Away from a Robust Negative Interest Rate Policy,” which is explained more there: