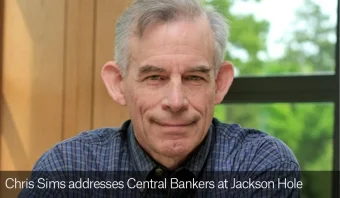

I was very pleased to be invited to the Jackson Hole monetary policy conference this past August. One of the highlights of the conference was Chris Sims’s lunchtime talk on the first main day of the conference, “Fiscal Policy, Monetary Policy and Central Bank Independence.” The fiscal theory of the price level is something I have been confused about for a long time. Chris Sims interpreted it from a remarkable simple point of view–a point of view very close in its logic to the way I analyze the transmission mechanism for interest rates cuts–including going to a negative interest rate or a deeper negative rate–in my posts

I confirmed my interpretation of what Chris was saying in a question I posed in the Q&A right after his talk. I still may have it wrong, but here is what I understood.

Why Lower Rates Increase Aggregate Demand and Higher Rates Reduce Aggregate Demand

Suppose real interest rates go down. Adding up spending from both sides of almost every borrower-lender relationship in which rates go down, aggregate demand should increase because:

- The negative shock to effective wealth of the lender is matched by an equal and opposite shock to the effective wealth of the borrower. This is the “Principle of Countervailing Wealth Effects” I discuss in the posts listed above. Long-term fixed rates can mute the shock to the effective wealth of both sides, but absent a big change in the inflation rate will still typically lead the borrower to feel better off with the change in rates and the lender to feel worse off in terms of annuity equivalents (whatever the asset values on paper).

- In almost all cases, the marginal propensity to consume is higher for the borrower than for the lender, so that adding up the effects on borrower and lender, the wealth effects add up to an increase in spending. The particular marginal propensity to consume (MPC) that matters is the marginal propensity to consume of the borrower out of reductions in interest expenses and the marginal propensity to consume of the lender out of interest earnings.

- In addition to the wealth effects on the non-interest spending of the borrower and lender, there is a substitution effect on both borrower and lender toward spending more now simply because spending now is relatively cheaper compared to spending later when the interest rate is lower. (For the lender alone, the wealth effect may easily overwhelm the substitution effect, so that the lender may spend less when interest rates go down, but for the borrower and lender combined the wealth effect and substitution effect both go in the same direction given 1 and 2: toward more non-interest spending when the rate goes down.)

What if interest rates go up? Then, adding up spending from both sides of almost every borrower-lender relationship in which rates go up, aggregate demand should decrease because:

- The positive shock to the effective wealth of the lender is matched by an equal and opposite shock to the effective wealth of the borrower–the “Principle of Countervailing Wealth Effects.” Long-term fixed rates can mute the shock to the effective wealth of both sides, but absent a big change in the inflation rate will still typically lead the lender to feel better off with the change in rates and the borrower to feel worse off in terms of annuity equivalents (whatever the asset values on paper).

- In almost all cases, the marginal propensity to consume is higher for the borrower than for the lender, so that adding up the effects on borrower and lender, the wealth effects add up to a reduction in spending. The particular MPC that matters is the marginal propensity to consume of the borrower out of reductions in interest expenses and the MPC of the lender out of interest earnings.

- In addition to the wealth effects on the non-interest spending of the borrower and lender, there is a substitution effect on both borrower and lender toward spending less now simply because spending now is relatively more expensive compared to spending later when the interest rate is higher. (For the lender alone, the wealth effect may easily overwhelm the substitution effect, so that the lender may spend more when interest rates go up, but for the borrower and lender combined the wealth effect and substitution effect both go in the same direction given 1 and 2: toward less non-interest spending when the rate goes up.)

The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level Points to the Exception

The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level comes into play when there is an exception to the rule that the borrower has a higher marginal propensity to consume than the lender. This has happened historically along the path to hyperinflations. The key borrower-lender relationship for understanding hyperinflations is the one in which the government is the borrower and bond-holders are the lenders. If inflation and interest rates are changing rapidly the wealth effects on both sides of the borrower-lender relationship in which the government is the borrower can have extra complexities, but the Principle of Countervailing Wealth Effects still applies: any effective gain in wealth to the government is an effective loss in wealth to the bond-holders and any effective loss in wealth to the government is an effective gain in wealth to the bond-holders.

One possible issue is if there is an unexpected increase in inflation that reduces even the annuity equivalent of long-term government bonds, so that the higher inflation increases aggregate demand through a higher government propensity to consume out of that inflation windfall than the reduction in spending to those who have had the annuity equivalent of their bonds eroded by inflation.

Another possible issue is related to the one envisioned in Thomas Sargent and Neil Wallace’s “Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic.” Suppose government borrowing is short-term and that the markets demand inflation compensation according to the Fisher equation, and that the central bank pushes up the real interest rate as inflation goes up. If the government reduces non-interest spending more than the bond-holders raise their spending as its real interest costs go up, then the situation is stable. But if the government keeps its non-interest spending roughly the same (financing the rising deficit out of additional borrowing), then any increase in bond-holder spending will result in an increase in aggregate demand. Unless aggregate demand goes down as a result of the effect of rising real rates on other borrower-lender relationships, the situation will be unstable. That instability can easily lead to hyperinflation.

Failure of Stabilization with a Lower Bound on Rates

Now consider the opposite situation from a hyperinflation. Suppose the economy starts with aggregate demand below what would keep the economy at the natural level of output. Interest rate cuts should raise aggregate demand according to the logic his post begins with. But if interest rate cuts are stopped short by a lower bound on rates, there may still be a deficiency in aggregate demand. And the markets, knowing that balance may not be reachable given the lower bound on rates, will not have future expectations that are as stabilizing as one would hope.

How Eliminating the Zero Lower Bound Leads to Stability

As long as rates can go as far down as needed, the logic of countervailing wealth effects–with borrowers having a higher MPC than lenders–ensures that aggregate demand will eventually rise to equal the natural level of output. Expectations of this will exert a stabilizing influence. The only potential problem is if important borrowers have lower marginal propensities to consume than the lenders on the other side of that borrower-lender relationship. The most plausible case of such a failure would be the government as borrower. But even a government in the grip of austerity because of a concern about budget deficits and national debt, is likely to have a relatively high marginal propensity to consume out of interest savings because those interest savings are manifested as a lower budget deficit–as conventionally measured–than the government would otherwise face. That is, is it really plausible that even a government in the grip of an austerity policy would spend less on non-interest items than it otherwise would because its interest expenses went down? That doesn’t seem plausible to me. Whatever reduction in non-interest spending the austerity approach lead to in itself, a low enough interest rate should reduce interest expenses enough that the government should begin spending more on non-interest items. I would be surprised if it isn’t close to 1 for 1 (MPC = 100%) in an environment where many people will be pushing the government to spend more, and for austerity proponents, pointing to a high budget deficit is one of the few effective ways of pushing back on that pressure to spend more.

How, in the Event, the Stabilization Mechanisms Need Not Be So Fiscal After All

The confidence that a low enough interest rate would bring forth enough additional aggregate demand to equal the natural level of output, plus the confidence that the central bank can and will lower the interest rate as much as necessary (having eliminated the zero lower bound) will make the economy stable. And part of that confidence may be knowing that in extremis the interest rate mechanisms described above would lead to more government spending on non-interest items as the central bank cut rates. But that does not mean that (given the initial recessionary situation) equilibrium would, in fact, be restored by a large increase in government spending on non-interest items. Knowing that the economy would return to the natural level of output, investment would be more robust. And even if there is still a big deficiency of aggregate demand, interest rate cuts raise aggregate demand through all the other borrower-lender relationships as well–many of them relationships in which the government is not involved. So it is quite possible for aggregate demand to be restored to equilibrium with the natural level of output with a relatively modest response of government spending on non-interest items as interest rates drop. Indeed, it is quite possible for the direct effect of an austerity policy to exceed the effect of interest rate cuts on government spending on non-interest items, so that government spending on non-interest items remains below normal during the recovery. Aggregate demand doesn’t have to come from the government. Interest rate cuts will guarantee that it comes from somewhere–unless the whole thing is destabilized by implausible expectations of an implausibly low government marginal propensity to consume out of interest rate savings.

Why There Is an Asymmetry Between Hyperinflation and Stabilization in the Absence of a Lower Bound on Interest Rates

Because cutting non-interest spending can be very difficult, it can and does happen that a government sometimes does have a low marginal propensity to cut non-interest spending as interest expense increases. But in a serious recession when there will be clamoring for more spending from all sides, there is nothing likely to stand in the way of even a quite austere government increasing government spending on non-interest items somewhat relative to what spending on non-interest items would have been had interest expenses been higher. On the other side of the transaction, the typical MPC of government bond-holders is quite low. And there are many, many other borrower-lender relationships in which borrowers unquestionably have a higher MPC than the lenders on the other side of the transaction. Finally, all of that leaves out the substitution effect, which can be quite powerful in raising aggregate demand in response to interest rate cuts, once one is comparing it to the sum of wealth effects for the borrowers and lenders on both sides of a transaction rather than to the wealth effect for only the lenders.

Conclusion

Anyone who forgets to think about borrowers will never understand the transmission mechanism through which interest rates affect the economy. Thinking about borrowers as well as lenders shows just how powerful cutting rates can be in stabilizing the economy once the lower bound on interest rates has been eliminated.