If Large Pecuniary Interests were Concerned in Denying the Attraction of Gravitation

“… it is true, as Macaulay said, that if large pecuniary interests were concerned in denying the attraction of gravitation, that most obvious of physical facts would have disputers.”

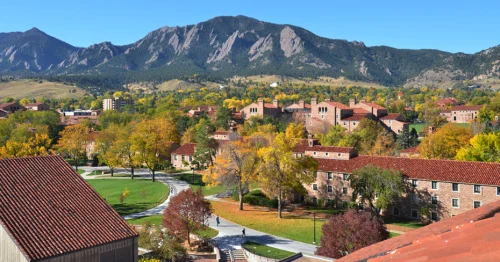

Miles Moves to the University of Colorado Boulder

Beginning September 1, 2016, I will be a Professor of Economics at the University of Colorado Boulder. Eugene D. Eaton Jr. gave a large gift to the University of Colorado, of which a portion endows the Eugene D. Eaton Jr. Chair that I will hold.

I very much enjoyed my 29 years at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where I started with a brand new PhD in 1987. Because of my many years of service there, I am able to retire from the University of MIchigan rather than resign, and expect soon to be an Emeritus Professor of Economics and Emeritus Research Professor of Survey Research of the University of Michigan.

I think both the University of Colorado Boulder and the University of Michigan Economics Departments have a bright future–the University of Michigan Economics Department for well-known reasons. The University of Colorado Boulder has a recruiting asset that I did not fully appreciate until I arrived here: Colorado is much more beautiful than I had realized when I decided to come here. My wife Gail and I live next to walking trails that give us a wonderful view of the sunsets on the mountains during our evening walks. And we enjoy balmy breezes eating breakfast out of doors on a deck with a view of the mountains almost every day. All it will take to successfully recruit many other economists is to combine that beauty with the kind of fully competitive salary and teaching package they put together in my case.

When I first started talking to the University of Colorado Boulder Economics Department I emphasized that I was looking for help in dealing with the time crunch I face from pursuing a writing career as a blogger, part-time journalist, and monetary policy activist as well as pursuing many lines of academic research and a full life outside of work. I am very pleased to have the support to try to do it all.

Unlike many successful recruitments, this one did not stem from any substantial prior connection with other economists at my new university. Based on the small amount of time I have known them, I am quite impressed.

In talking to my colleagues at the University of Michigan about my impending move, I was surprised that among the arguments to stay at the University of Michigan, there were several accounts from colleagues who had moved from being a professor at some other university to the University of Michigan of how moving to a new environment had given them a creative boost. I look forward to the new insights I gain from a new environment.

A picture I took of the moon over a hill not far from my new home

A picture I took of my new home from the nearby hill. Despite appearances, a full suite of gleaming retail stores and excellent restaurants is not far away.

Q&A With Gerard MacDonell on My Presentation “Enabling Deeper Negative Interest Rates by Managing the Side Effects of a Zero Paper Currency Interest Rate”

I am grateful to Gerard MacDonell for permission to share this exchange. I answered some emails full of questions with my own email interleaving my answers about my presentation “Enabling Deeper Negative Rates by Managing the Side Effects of a Zero Paper Currency Interest Rate.” You can see a shorter (20 minute) version of that presentation here.

Gerard: We have never met, but Noah Smith speaks very highly of you and told me I should read your stuff. I loved the series of tweets where you got talked down from endorsing Cochrane’s work on the cost of regulation. I had the exact same experience.

I really enjoyed your deck on negative interest rates. I used to work at a hedge fund and was close with a guy who traded banks who was absolutely convinced that low interest rates crushed margins. My own priors were in line with your thoughts, but this guy made money and the correlation between daily stock prices moves and the forward pricing of the Fed seemed to confirm his view. I guess there is a “behavioral” issue there, as you put it. My guess is that the behavioral issue is at the banks and their clients rather than in how the markets react to the reality in place. In other words, the traders are processing the reality fine, but the reality itself has a behavioral component?

I wonder if it might disappear as the experience with very low rates lengthens. You might want to address that in your work on this. I bet there would be a lot of interest.

Miles: This Powerpoint file for the new paper Ruchir and I are working on has some relevant graphs–and I think you will be interested in it generally. We would be glad for comments on it. It is quite new and we are eager to improve it.

Gerard: I really liked it and it is why I contacted you in the first place. Before I offer thoughts on it, I should be clear that I am not an academic. I have an MA from Queen’s in Kingston Ontario and have spent 25 years as a business economist. I was most recently at SAC for 11 years and prior to that on JPM’s buy side for about 5 years. In those roles, I tried to arb the gap between what Wall Street knows and what academics know, but I am not an academic. Rather, I am inclined to the dreaded “literary” approach to economics, as Noah dismissively calls it! ;)

I don’t want to waste your time, so I will offer my thoughts in bullet form.

You might want to mention Neo Fisherianism if only to be clear that you dismiss it. Clearly, you assume it is wrong.

Miles: If you mean the idea that high interest rates raise inflation and low interest rates make inflation fall, yes, I think it is pretty silly. My main intended audience doesn’t believe that anyway, so I haven’t spent a lot of time addressing it.

Gerard: This may be idiosyncratic of me and less interesting to you, but I am very interested in what causes banks not to marginal cost price. I guess it is some combination of market power and behaviorism. It would be great to get to the bottom of that. Practitioners insist that the slippage between mortgage rates and policy rates that you show in one of your charts may UNDERSTATE the issue. Some claim banks have minimum profitability targets and will ream mortgagers to get back the damage to profits caused by negative policy rates. That is pretty slippery economics, but I know the idea is out there. If you could demolish it, then that would be a great contribution and I know Wall Street would be very interested in that. But again, that is idiosyncratic of me.

Miles: The basic problem is that banks always want more profits. So if they could raise profits by raising lending rates, why not do that before? Something has to change as a result of the negative rates. I think the relevant thing that might change given negative rates is that the regulatory authority might feel bad for the banks and be less strict in anti-trust enforcement. In the same direction, in Switzerland, the central bank wanted lower rates in relation to the foreign exchange markets, but actually wanted higher mortgage rates because they feared a house-price bubble. So they encouraged the banks to keep high mortgage rates.

Absent a shift in implicit or explicit government policy about banks raising lending rates, the story gets very difficult. It needs to be banks doing something to help with a short-term liquidity crunch at the expense of long-term profits.

Gerard: Willem Buiter has written on time stamping reserves to get around the lower bound. I found his piece dense, and you have probably already read it. But just in case.

Miles: I have credited Buiter in several ways. Most memorably, he appears as “Willem the Wise Warlock” in my children’s story about negative rates.

Gerard: In your first chart, you channel Summers in mentioning that curing recessions usually takes rate cuts of more than 5%. I think your chart highlights that AND that the zero bound is why rates stopped falling. Rates are high, not low! Or at least they have been. Maybe that is your main point and that the title might reflect that?

Miles: Yes. Large cuts in interest rates are standard in a recession if the zero lower bound doesn’t get in the way. At the Brookings conference on negative rates, they said that the usual model suggests that rates should have been cut to -6% in 2009, rather than the -4% I suggested in “America’s Big Monetary Policy Mistake: How Negative Interest Rates Could Have Stopped the Great Recession in Its Tracks”

Gerard: Some might argue with you that closing the Gold Window was a monetary policy regime shift. It allowed more inflation as a matter of fact, but it need not have. Minor point.

Miles: Actually, this is an excellent parallel. It is the cut in the target rate and the interest rate on reserves that is the main monetary policy instrument. Going off paper so that the paper currency interest rate can go negative can be viewed as enabling those cuts in the target rate and the interest rate on reserves.

Gerard: On slide 11, is being “subtle” really a feature? Maybe you want to hammer households over the head? Or are you worried about the income effect?

I don’t need any transmission from regular households seeing negative deposit rates. And the transmission from lower lending rates to households will mostly be from lower but still positive rates for cars, mortgages, appliances, etc. Credit card rates start so high, they would still be high even after cuts.

On slide 16, I know what you mean by “backed by”, but what you really mean is any sort of currency holdings. Don’t let funds fake it.

Yes, defining “backed by paper currency” would probably mean a strict limit on the fraction of assets that could be paper currency.

On slide 17, you see mortgage rates actually go up a bit there. Small, but riles up the practitioners.

Miles: Mortgage rates went down in Denmark and Sweden. The Swiss National Bank effectively encouraged banks to raise mortgage rates, and the banks obliged. Japan has only cut rates by a tenth of a percentage point, so whatever happened to mortgage rates there is unlikely to have anything to do with that small cut in rates, other than the mechanism of the authorities feeling sorry for the banks and lightening up on anti-trust attitudes.

Gerard: On slide 18, I may well be wrong here, but isn’t a tiered deposit rate system just an untiered system plus a subsidy to the banks? I think it would be better to deal with the behavioral/market power issues directly. If not, why hide what is really happening? Call it what it is: a subsidy to reflect that the standard banking model has not worked so well with negative rates. Or maybe I am wrong technically on that? Either way, honesty first!

I think calling it “an effective subsidy through the interest on reserves formula as I do is pretty honest.” It is appropriate to point to the formal mechanism through which the effective subsidy is provided is appropriate.

On slide 43, I love your point about helicopter money. So true. Related, eliminating currency would further weaken the case for heli money, unless you unwound the regime change when rates went back positive. Not related to your main thesis, but fun in my view.

Miles: Did you see my post “Helicopter Drops of Money Are Not the Answer”?

Gerard: On slide 44, you say higher inflation is easier said than done. I so agree. And I think this relates to the heli money issue. The “calibration” issue with H money is not really resolved. The efforts at resolving it (Turner, Bernanke) are just taxes on the banking system, disguised as ongoing “money” finance.

The beauty of negative rates is that we have an excellent idea of how much each basis point does, since it is essentially the same

Slides 47-49 remind me of a pet peeve, again because I agree. I think much of the clarion call for higher rates to fight bubbles is related to confidence that higher rates will NOT work. People who benefit from bubbles or would be hurt by a serious effort to improve financial stability can hide behind the pretense that they are against bubbles — as evidenced by their whining about the Fed!

Miles: I agree. A large amount of debate about various issues is really talking points by people who have a particular self-interest. The main solution to financial stability problems is very high equity requirements. That solution is against the self-interest of those who benefit from taking risks with an implicit taxpayer guarantee if things go south.

Gerard: The contrarian SWF is a very fun idea. I see that Blanchard believes that QE was so potent that Macro textbooks should now include it as the one (worth-mentioning) determinant of the term premium. That actually made me laugh or cry. But market segmentation would seem to be a bigger issue in risk assets, so I think that idea is cool. I think Delong has blogged on it too, no?

Miles: Yes.

Gerard: Speaking of QE, on 57 you say it was “seen as radical” but later “gained traction.” IMHO, how it was “seen” is irrelevant. Whether it gained traction is also a bit subjective. Does the evidence show it worked as indicated on the label? Personally, I would say not. But Noah has the hate mail to show many disagree.

Miles: One of the main pieces of evidence is the better recovery that the US and UK have had as compared to the eurozone. Also, asset markets move with QE announcements, so it is clear the markets believe QE has effects.

Jeff Guo on Tontines →

Tontines used to be a ridiculously popular form of annuities in America. Could they be again?

John Stuart Mill—The Great Temptation: Telling Others What to Do

In the 15th paragraph of the “Introductory” chapter of On Liberty, John Stuart Mill writes:

Apart from the peculiar tenets of individual thinkers, there is also in the world at large an increasing inclination to stretch unduly the powers of society over the individual, both by the force of opinion and even by that of legislation: and as the tendency of all the changes taking place in the world is to strengthen society, and diminish the power of the individual, this encroachment is not one of the evils which tend spontaneously to disappear, but, on the contrary, to grow more and more formidable. The disposition of mankind, whether as rulers or as fellow-citizens, to impose their own opinions and inclinations as a rule of conduct on others, is so energetically supported by some of the best and by some of the worst feelings incident to human nature, that it is hardly ever kept under restraint by anything but want of power; and as the power is not declining, but growing, unless a strong barrier of moral conviction can be raised against the mischief, we must expect, in the present circumstances of the world, to see it increase.

Here is Robin Hanson on the same theme:

Humans clearly attend closely to status, an important part of status is dominance, and a key way we show dominance is to tell others what to do. Whoever gets to tell someone else what to do is dominating, and affirming their own status. But we are also clearly built to not notice most of our status moves, and so we attribute them to other motives. And as long as we are making up motives, we might as well make up the most admired of motives, altruism.

So we tend to think we tell others what to do in order to help them, and not to dominate them. In particular we tend to think we tell fat folks what to do, and control their behavior, because this will help those fat folks. For example, many support taxing soda or fast food in order to help fat folks.

You can see me wrestling with the desire to tax soda in my post “John Stuart Mill on Running Other People’s Lives.” The temptation to run other people’s lives throught public policy should not be underestimated. And without at least recognizing the temptation, there is little hope that we can fight it.

In these examples, the concern is with telling people what to do, ostensibly for their own good. But it is also pleasant to tell people what to do even without any pretense it is for their own good. One of the great pleasures of being a bureaucrat is getting to tell people what to do. And I suspect that getting to tell people what to do is part of the attraction of being one of the police. To keep bureaucracies and the police democratically legitimate, bureaucrats and police must treat everyone they deal with professionally with dignity. Maybe many people should be stopped by the police in order to keep crime down. But it is a disgrace if those interactions are not made absolutely as pleasant as possible for those being stopped.

Given my demographic category, my experience in being stopped by the police is limited, but I have noticed dramatic variations from place to place in how nice officials at airport screening are and dramatic variations from place to place in how nice officials at the Department of Motor Vehicles are. So I know it is not impossible to be nice. I am saying it is not just nice to be nice, but a moral requirement for the state–which makes people deal with these officials at the point of a gun (or on pain of the loss of great boons such as driving or flying)–not to train such folks to be nice. The necessity of such training follows from the great fun there is in bossing people around and telling them what to do, which is guaranteed to come out without very particular training to combat it.

Postscript: It is not lost on me that even in a blog post like this, I am telling people what to do. What fun! I hope in this particular case I am not doing any harm by giving in to the temptation.

Henry George: Why the Citizenry Needs to Understand Economics

“We may safely leave many branches of knowledge to such as can devote themselves to special pursuits. We may safely accept what chemists tell us of chemistry, or astronomers of astronomy, or philologists of the development of language, or anatomists of our internal structure, for not only are there in such investigations no pecuniary temptations to warp the judgment, but the ordinary duties of men and of citizens do not call for such special knowledge, and the great body of a people may entertain the crudest notions as to such things and yet lead happy and useful lives. Far different, however, is it with matters which relate to the production and distribution of wealth, and which thus directly affect the comfort and livelihood of men. The intelligence which can alone safely guide in these matters must be the intelligence of the masses, for as to such things it is the common opinion, and not the opinion of the learned few, that finds expression in legislation.”

Alva Noë: Should Teachers Ask Students To Check Their Devices At The Classroom Door? →

A hat tip to Joseph Kimball for this link.

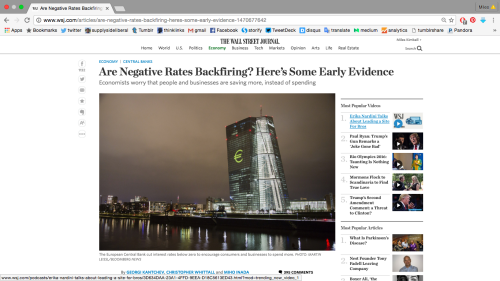

Georgi Kantchev, Christopher Whittall and Miho Inada Write a Balanced Assessment of Negative Rates for the Wall Street Journal

I had a very interesting interview with Georgi Kantchev a bit ago that is nicely reflected in an August 8 Wall Street Journal article he wrote with Christopher Whittall and Miho Inada. Despite the negative tone of the headline, and its collection of person-in-the-street quotations from people horrified by negative interest rates, in its analysis, it is actually quite a nuanced and balanced article.

A. Consider the following pairs of quotations:

1a. Some economists now believe negative rates can have an unintended psychological effect by communicating fear over the growth outlook and the central bank’s ability to manage it.

“The signal to the consumer is that something is wrong—it’s a crisis measure,” says Carl Hammer, chief currency strategist at Swedish bank SEB.

1b. University of Michigan economist Miles Kimball believes rates should be lowered even deeper into negative territory. If people are getting scared by negative rates, he says, it is the fault of central banks’ inability to communicate effectively, not the policy itself.

“They should say that this is a normal tool of policy,” he says, “and then people wouldn’t freak out.”

2a. In Germany, Europe’s largest economy and a nation known for thrift, savings as a percentage of disposable household income rose to 9.7% in 2015, according to preliminary data from the OECD. That is the highest rate since 2010, and the OECD expects the savings rate to rise further this year, to 10.4%.

2b. In the broader eurozone, where saving isn’t as ingrained in the psyche as in Germany, the household savings rate has edged lower since negative interest rates were introduced in 2014.

3a. Yves Mersch, a member of the ECB’s executive board, said in June that it is possible “households are hoarding even more” because they need to save more to build up the same amount of wealth over the same time span.

3b. Peter Praet, the ECB’s chief economist, says the focus should also be on borrowers, who are more inclined to spend than savers, and are seeing a boost to their disposable income because ultralow rates reduce the cost of servicing debt.

B. In the second and third pairs of quotations, the authors of the article show an understanding of the principle I enunciated in “Even Central Bankers Need Lessons on the Transmission Mechanism for Negative Interest Rates”:

The Principle of Countervailing Wealth Effects: It is easy to forget about some of the wealth effects. Applying the general principle that all the wealth effects cancel–other than overall expansion of the economy and differences in the marginal propensity to consume across economic actors can help in making sure one hasn’t missed a wealth effect, much as double-entry accounting helps in making sure one doesn’t miss something. An example of a particularly large wealth effect that is easy to miss is that a fall in interest rates raises the present discounted value of household labor income. The other principle that helps to avoid missing a wealth effect is to remember that there is always another side to every borrowing-lending relationship. If the economic actor on one side of the borrowing-lending relationship gets a negative hit to effective wealth, the economic actor on the other side will get a positive boost to effective wealth–again with the exception of the overall expansion of the economy. …

I discussed this principle again in “Responding to Joseph Stiglitz on Negative Interest Rates”:

… because there are two parties to every borrower-lender relationship, what is a negative wealth effect to one party is a positive wealth effect to the other. And on the whole, borrowers–who tend to get a wealth effect boost from lower rates–are better spenders than lenders. So if all the wealth effects are accounted for rather than cherry-picking a wealth effect here or there, they will be in the direction of greater stimulus from lower rates. Here is the overall story about transmission mechanisms for lower rates, in the negative region as well as the positive region: In any nook or cranny of the economy where interest rates fall, whether in the positive or negative region, those lower interest rates create more aggregate demand by a substitution effect on both the borrower and lender, while other than any expansion of the economy overall, wealth effects that can be large for individual economic actors largely cancel out in the aggregate.

Anyone who discusses the effects of negative interest rates by talking only about lenders without talking about borrowers is missing at least half of the story. Georgi Kantchev, Christopher Whittall and Miho Inada avoid that mistake.

I give a non-obvious example of this principle of considering borrowers as well as lenders in “Responding to Joseph Stiglitz on Negative Interest Rates”:

…think of senior citizens who lend instead to the federal government. Lower interest rates reduce the deficit and tend to lead to more government spending fairly directly by deficit reduction rules biting less. Even though senior citizens have a high marginal propensity to consume, I think the effects of deficit numbers on government behavior make the effective marginal propensity to consume of the federal government out of a change in interest expense even higher. Those who like the idea of fiscal stimulus should be happy about this stimulus from negative interest rates–especially since the negative wealth effect is only for the relatively well-off senior citizens who are not just living on social security, but have interest income to live on on top of that.

C. You might be interested in the email I sent to Georgi:

Dear Georgi,

It was great talking to you. Let me try to remember all the links I promised you:

1. I have links to everything I have written (including two academic policy papers) on negative interest rates in this bibliographic post that I update every few weeks:

2. You can see the video of the afternoon session of the Brookings conference I mentioned here:

My 20 minute talk comes first, giving more background on my recommendations. You can hear reactions to what I said as well. The panel discussion after is where you can hear several people say that the interest rate movement in at least the case of Japan is small compared to other things going on.

3. The actual Brookings website for that conference has both the afternoon session and the morning session:

This morning session has a lot of excellent talks, including the heavy-duty talk by Massimo Rostagno about his work with coauthors looking at what the markets believe is the lower bound on interest rates and the value Massimo sees in having negative rates in order to lower the market’s beliefs about what the lower bound on interest rates is, which allows long-term rates affected by QE to fall further. We talked about this in the context of central bank communication policy and the value of telling the markets that you can and will take interest rates as low as necessary. (The key point of my work is that there is no lower bound on interest rates if a central bank uses an appropriate mix of policies.)

4. Here is Naranaya Kocherlakota (who recently stepped down as President of the Minneapolis Fed) saying that negative rates should be treated as a normal part of monetary policy as we discussed:

and here is my reaction:

I had forgotten that this was a few weeks before he started writing for Bloomberg View. Narayana Kocherlakota has written a lot about central bank communication and negative interest rates in his Bloomberg View columns:

5. Here is my advice that central banks should use the interest-on-reserves formula to effectively subsidize the provision of zero rates (rather than negative rates) to small household accounts:

6. Here is a relatively heavy-duty post taking on Mark Carney to argue that there are many, many channels through which cutting interest rates–including cutting interest rates in the negative region–will stimulate the economy:

Not all of these channels involve banks. So a low enough rate can get all needed stimulus even if banks are malfunctioning. (Of course, it is bad directly if banks are malfunctioning; I am just saying that monetary policy can do its most basic job even if they are.)

I also addressed this issue here:

7. On the evidence that negative interest rates have the usual effects of interest rate cuts on financial markets despite some commentary to the contrary by bankers who are busy lobbying against negative rates, see this very nice post by Scott Sumner:

In case that link doesn’t work, I also got Scott’s permission to mirror it on my blog:

Let me know if there is anything else I forgot or if you have any other questions. I’d love to talk to you again sometime.

–Miles

The Progress of Negative Interest Rate Policy Understanding

Zurich

Quite a few months back (about last Fall), I had an interview with a journalist in Zurich that did not result in an article. For that interview I had prepared some thoughts that I wanted to share with you. Keep in mind

1. Because of my visits to central banks, these proposals are getting wide discussion within central banks, and because of the two London conferences in May 2015, between central banks as well. Under the surface, there is a much bigger consensus than what you would assume.

2. The two countries I would bet on to introduce a negative paper currency interest rate first are the UK–as I predicted early on before even visiting (see “Could the UK Be the First Country to Adopt Electronic Money?” ) and his been borne out by subsequent events, and Switzerland, which currently has rates in the deepest negative territory (see “The Swiss National Bank Means Business with Its Negative Rates” and “Swiss “Pioneers! The Swiss as the Vanguard for Negative Interest Rates.”

3. The economics of my proposal is clear, and has withstood detailed questioning by central bankers all over the world. But with few exceptions, those who serve on monetary policy committees have sensitive political antennae and are worried about the politics of a negative paper currency interest rate.

4. Because of the political sensitivity of a negative paper currency interest rate, the only central bank officials to have alluded to it publicly are Bank of England Chief Economist Andrew Haldane (who refers directly to my work) and the Swiss National Bank officials involved in cosponsoring the conference on “Removing the Zero Lower Bound on Interest Rates” in London on May 18, 2015. So far, other central banks do not want to discuss my solution publicly, but there are many central bank staff economists around the world who are enthusiastic, believing as I do that from a technical point of view it would work well and solve an important problem.

Update Since Last Fall: Three former members of the FOMC have now discussed my proposal: Ben Bernanke, Narayana Kocherlakota and Donald Kohn. You can hear all of them talk about it in this video from the Brookings conference on negative interest rates at which I spoke. Ben Bernanke was also asked about my proposal in an interview by Ezra Klein; you can see his answer here. Narayana Kocherlakota also wrote about my proposal here.

5. One important virtue of my approach is its continuity with the current system: in small doses it is almost indistinguishable to ordinary households from the way we do things now.

6. If I were closely consulted on introducing a paper currency interest rate through a crawling-peg exchange rate between paper currency and electronic money, I would advise making it sound very bureaucratic and boring. I would start very subtly, with a dose small enough that there would be no chance of any significant negative side effects.

7. A cut of 50 basis points by the SNB would be well worth doing because it would have a substantial effect on foreign exchange rate for Swiss Francs.

8. Even if you do not want to cut interest rates now, you want to prepared for the next recession.

9. An exchange rate on paper money by the SNB would be a blessing for other countries. They could see in Switzerland that it works. Moreover, it could have an important stabilizing effect on world financial markets because it would help allay the fear that the world economy might be doomed to replicate the performance of the Japanese economy in the last two decades.

See links to everything I have written about negative interest rates in my bibliographic post “How and Why to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound: A Reader’s Guide.”

Religion as Literature

“If every trace of any single religion were wiped out and nothing were passed on, it would never be created exactly that way again. There might be some other nonsense in its place, but not that exact nonsense. If all of science were wiped out, it would still be true, and someone would find a way to figure it all out again.”

Penn Jillette, as quoted here.

This is a very interesting argument, but it sounds more negative for religion than it really is. The very same could be said for any piece of great literature or any great painting; and people don’t usually go around calling the works of William Shakespeare or the paintings of Pablo Picasso “nonsense,” even if strictly speaking they are.

Robert Frank on the Power of Modesty →

People who are aware of their good fortune make more attractive teammates.

Quartz #67—>Nationalists vs. Cosmopolitans: Social Scientists Need to Learn from Their Brexit Blunder

Here is the full text of my 67th Quartz column, “Social scientists need to learn from their Brexit blunder, so we can learn from them,” now brought home to supplysideliberal.com. It was first published on June 29, 2016. Links to all my other columns can be found here.

I give my reasoning behind the first sentence of this column in my July 10, 2016 sermon “Us and Them.”

If you want to mirror the content of this post on another site, that is possible for a limited time if you read the legal notice at this link and include both a link to the original Quartz column and the following copyright notice:

© June 29, 2016: Miles Kimball, as first published on Quartz. Used by permission according to a temporary nonexclusive license expiring June 30, 2020. All rights reserved.

The worst thing about Brexit is a key reason Brexit gained so much support: opposition to immigration. Advocates for the UK leaving the European Union were not shy about pointing to opposition to immigration as a key to their success. Nigel Farage captured some of that spirit by declaring “This is a victory for ordinary people, for good people, for decent people.”

The rise in inequality and serious monetary policy mistakes—including the eurozone’s requiring many disparate economies to share monetary policy with Germany—may have set the stage for rebellion against the status quo. But Donald Trump’s “I love to see people take their country back” expresses the nationalism behind the direction of rebellion implicit in Brexit.

One of the most revealing pieces of data on the Brexit vote is Eric Kaufmann’s analysis of Brexit support among the over 24,000 survey respondents in the British Election Study. Support for Brexit was much higher among those who supported capital punishment, and support for the EU was much lower among respondents who supported the public whipping of sex offenders. That is, “hardliners” were much more likely to support Brexit.

I have written the above as if we know what happened with Brexit. And although I think I have the general drift of things right, one of the big messages of Brexit in the UK and of the rise of Donald Trump in the US is that social scientists need to up their game dramatically in understanding what people want and how they think. For some time, social scientists have made a special effort to understand ethnic and sexual minorities. But given how different hardliners are from the people many academic social scientists usually hang out with, and how many hardliners there are, social scientists need to spend a lot more time studying this group. (Though marred by condescension toward “conservatives,” George Lakoff’s book Moral Politics is an excellent place for academics to start in an effort to understand the hardliner worldview.)

In order to give non-pejorative labels to both sides, let me call those who, like me, favor more open immigration “Cosmopolitans” and those who favor more restrictive immigration (and other policies in the same spirit) “Nationalists.” As a Cosmopolitan, what I most want to know from social science is what interventions can help make people more accepting of foreigners. Somewhat controversially, it is now common in the US for elementary school teachers to make efforts to instill pro-environmental attitudes in schoolchildren. Whether or not those efforts make a difference to children’s attitudes, are there interventions or lessons that can make schoolchildren and the adults they grow up to be likely to feel more positive about the foreign-born in their midst? For example, having had a very good experience learning foreign languages on my commute by listening to Pimsleur CDs in my car, I wonder whether dramatically more effective Spanish language instruction for school children following those principles of audio- and recall-based learning with repetition at carefully graded intervals might make a difference in attitudes toward Hispanic culture and toward Hispanics themselves in the US.

Although it is the province of social scientists to test interventions intended to improve attitudes toward the foreign-born, many of the best interventions will be created by writers, artists, script-writers, directors, and others in the humanities. There are also many other marginalized groups in society, but the strength of anti-foreigner attitudes suggests the need for imaginative entertainment and cultural events to help people identify with human beings who were born in other countries.

It is obvious to anyone except those with their heads in the sand that Brexit in the UK and the rise of Donald Trump in the US are a wake-up call to the relatively Cosmopolitan elites who have been running those countries. But that doesn’t mean the Cosmopolitan faction among the elites must surrender to the Nationalists. Cosmopolitan elites are powerful, and shouldn’t go down without a fight.

What is clear is that the strategy of shaming Nationalists and ethnocentrists who say negative things about other groups has its limitations. My grandmother used to quote Dale Carnegie’s now politically incorrect couplet:

A man convinced against his will,

Is of the same opinion still.

Shaming may work to a point, but what is needed now is genuine persuasion about the humanity that we all share, regardless of where on earth we are born.

In addition to such gentle efforts to help people become more accepting of the foreign-born, there is also, in the US, the possibility of an immigrant-voter “nuclear option” for cementing a Cosmopolitan victory—one that works only if Donald Trump goes down in flames and takes the Republican Senate and House majorities down with him. In that situation the Democrats (perhaps with the help of the filibuster-busting “nuclear option”)–could force through a true “amnesty” bill for illegal immigrants, including full naturalization. This would bring millions of additional immigrants onto the voting rolls—the latest in many historical expansions of the franchise.

Back in 1996, historians William Strauss and Neil Howe predicted in The Fourth Turning that the first two decades of the 21st century would bring a political crisis when the senescence of earlier generations finally deprived polarized Baby Boomers of effective adult guidance. Whatever one’s judgment about the overall merits of the Strauss-Howe generational theory, this particular prediction has come true. In such a crisis, it really matters how things get resolved. History is written, by and large, by the victors, so whichever side comes out on top—Nationalists or Cosmopolitans—will look good in the history books.

Q&A: Why is Fiscal Policy So Close to Being Neutral in Many Modern Macro Models?

Q: Hi Miles: Sorry to bother you, but I’ve gotten hornswoggled into teaching macro again and there is one topic in kind of the evolution of macro that is eluding me.

And that question is, how did we get to fiscal policy irrelevance/ineffectiveness in the new keynesian dynamic model?

Is it a presumed Fed response to offset? Is it Ricardian Equivalence? Is it just that VARs show little response?

Can you give me a pointer about where to look?

A: This is something I teach in my graduate macro class. Fiscal policy irrelevance has nothing to do with sticky prices or not. It is all about investment. Without investment frictions, investment tends to be crowded out 1 for 1 by government purchases in both sticky-price and non-sticky-price models. (Let me ignore the effects on labor supply because of the impoverishment caused by higher G and also the opposite-direction effects of higher marginal taxes to pay for the higher G.) And that logic should extend to sticky wage models as well. Sticky prices don’t matter because aggregate demand doesn’t even go up. G up, I down.

Q-theory affects this in a different way than many people probably think. Q-theory is not really investment adjustment costs, it is investment smoothing, analogous to consumption smoothing. So it is totally forward looking. If a shock is going to last 4 or 5 years, then there is still fairly complete crowding out of investment

I think you will like my (unpublished) paper with Susanto Basu on investment planning costs. Here are its slides. (These are totally public.) But planning adjustment costs only let G stimulate the economy for 9 months are so (the same as the lag in the effect of monetary policy that comes from planning adjustment costs). I call that period of time the ultra-short run.

To the extent it seems that government purchases do have an affect on output longer than the ultra-short run, to me the leading candidates are:

- Monetary policy response. For example, when more military spending is needed as in Ramey and Shapiro, the central bank may be accomodative. This is speculative, I don’t know it to be true.

- Imperfect mobility of labor between production of capital and production of G. This is more credible in some areas than others. For example, building a government office building and a private office building should be doable by the same factors, so those shifts of factors between G and I should be easy. But the government has many other purchases of products of types that would be unusual in the private sector.

If fiscal policy is about tax cuts to increase C, there are the usual permanent income issues plus the issue of how easily C can crowd out I. But consumption smoothing is likely much stronger than investment smoothing a la Q-theory, so that probably does work, as implicitly assumed in my paper “Getting the Biggest Bang for the Buck in Fiscal Policy” in arguing for the greater effectiveness of credit policy.

Our Michigan PhD Chris Boehm has a paper on all of these issues that you should look at.

One reason I call myself a Monetarist rather than a New Keynesian is because of these issues with fiscal policy.