Live: So You Want to Save the World

Note: You can see the written text for this sermon in my earlier post “So You Want to Save the World.” Click on the picture above to see the video.

Don’t miss the other sermons I have posted:

A Partisan Nonpartisan Blog: Cutting Through Confusion Since 2012

Note: You can see the written text for this sermon in my earlier post “So You Want to Save the World.” Click on the picture above to see the video.

Don’t miss the other sermons I have posted:

This list of important practices for mental health seems very much on target, based on my own experience.

I am grateful to Leon Berkelmans for securing permission from the Australian to mirror his article here, which appeared in the Australian on September 12, 2015.

Below, Leon mentions New Zealand as a monetary policy innovator that might adopt negative interest rates. On that, see also “Michael Reddell: The Zero Lower Bound and Miles Kimball’s Visit to New Zealand.”

The world waits, feverishly, for next week’s Federal Reserve meeting. The FOMC could increase interest rates for the first time in almost a decade. Martin Sandbu, of the Financial Times, called this decision “the single most important imminent economic policy decision in the world”. But there’s an even more important issue in plain sight. And we are not talking about it.

It’s the zero lower bound on interest rates. The Fed will be increasing interest rates from that bound, where rates have been stuck since the end of 2008. Other major economies are stuck at the zero lower bound too. Japan has been there for a couple of decades. The ECB hit the zero lower bound a few years after the Fed, but it’s there now, and unlikely to exit any time soon.

Some European central banks have been able to implement rates slightly below zero, showing that small negative returns will be tolerated, but there is a limit.

In any case, the zero lower bound has been costly. One analysis by Federal Reserve economists suggested that unemployment would have been 3 percentage points lower in 2012 had they been able to cut interest rates to negative 4 per cent.

One might adopt the position that the global financial crisis was a freak event. We haven’t seen such extremes in central bank interest rate policy before. Once economies exit the current situation, we are unlikely to see them again in the future. I think such a position is wrong.

In 2012, in their World Economic Outlook, the IMF documented the gradual but sustained and relentless decline in real long-term interest rates over the last three decades.

This decline in real long-term rates will translate to lower short-term nominal rates, on average, over the cycle. That means the zero lower bound is more likely to be hit. This is true, no matter where you are. Every economy is likely to face this new future.

There are several possible responses to these developments, among them: rely on unconventional monetary policy, raise the inflation target, pursue fiscal activist policy, implement institutional changes so that negative interest rates are possible, or change the monetary framework away from inflation targeting.

Unconventional monetary policy, namely quantitative easing and forward guidance, has probably had its successes. A different study by Federal Reserve economists has suggested that unconventional policies subtracted one and a quarter percentage points from the unemployment rate.

However, there is uncertainty about how unconventional policies work. For example, in 2012 Michael Woodford, the doyen of academic monetary economists, suggested that quantitative easing, in particular, did not have the effects typically ascribed to it.

Moreover, he claimed that unconventional policies often caused financial markets to become more pessimistic, an unsavoury side effect for a policy that’s supposed to be stimulatory. The debate and academic inquiry rages on, and more work will be needed before economists can claim to have mastered unconventional policy.

Raising the inflation target would help. Olivier Blanchard, outgoing chief economist at the IMF, and Janet Yellen, chair of the Federal Reserve, have openly mused about the possibility. But questions remain here too. How do you raise the target, and make the new target credible, given that the old target had been changed?

Activist fiscal policy could provide stimulus when interest rates are stuck at zero. Peter Tulip, of the Reserve Bank, last year pointed out how this would ameliorate the costs of the zero lower bound.

It’s again a possibility, but I think there are open questions about the alacrity of the political process. Could it always be relied upon to do enough?

Changes could be implemented to make significant negative interest rates feasible. Ken Rogoff, a former IMF chief economist, has discussed the possibility of abolishing physical currency, which would do the trick. Moving away from an inflation target, towards something like nominal GDP targeting, could also work. Michael Woodford offered this as an alternative in the same 2012 paper I mentioned earlier. However, there are some shortcomings, especially in a small open economy like Australia, where a volatile terms of trade can play havoc with nominal GDP growth.

I’m not sure any solution is perfect. However, central banks should plan ahead. It’s unlikely that the future will look like the pre-GFC past. Planning on that basis will lead to tears and leave a guilty central bank looking jealously at an innovator that took the issue head on — perhaps an innovator like, gasp, New Zealand.

Leon Berkelmans is director, international economy, at the Lowy Institute for International Policy.

Marc Andreessen is the only billionaire I know to be following me on Twitter. This guest post on his blog “Software is Eating the World” (linked above) is useful for economists who want to get a little more sense of the real world of business. It is also helpful for people who want to enhance their “Shark Tank” viewing experience. (On “Shark Tank” also see my post “Shark Tank Markups.”)

Some of the reporting of Andrew Haldane’s September 18 speech “How low can you go?” skipped over key things he said. Here is the part of his speech where he explains how to break through the zero lower bound:

Negative interest rates on currency

That brings me to the third, and perhaps most radical and durable, option. It is one which brings together issues of currency and monetary policy. It involves finding a technological means either of levying a negative interest rate on currency, or of breaking the constraint physical currency imposes on setting such a rate (Buiter (2009)).

These options are not new. Over a century ago, Silvio Gesell proposed levying a stamp tax on currency to generate a negative interest rate (Gesell (1916)). Keynes discussed this scheme, approvingly, in the General Theory. More recently, a number of modern-day variants of the stamp tax on currency have been proposed – for example, by randomly invalidating banknotes by serial number (Mankiw (2009), Goodfriend (2000)).

A more radical proposal still would be to remove the ZLB constraint entirely by abolishing paper currency. This, too, has recently had its supporters (for example, Rogoff (2014)). As well as solving the ZLB problem, it has the added advantage of taxing illicit activities undertaken using paper currency, such as drug-dealing, at source.

A third option is to set an explicit exchange rate between paper currency and electronic (or bank) money. Having paper currency steadily depreciate relative to digital money effectively generates a negative interest rate on currency, provided electronic money is accepted by the public as the unit of account rather than currency. This again is an old idea (Eisler (1932)), recently revitalised and updated (for example, Kimball (2015)).

All of these options could, in principle, solve the ZLB problem. In practice, each of them faces a significant behavioural constraint. Government-backed currency is a social convention, certainly as the unit of account and to lesser extent as a medium of exchange. These social conventions are not easily shifted, whether by taxing, switching or abolishing them. That is why, despite its seeming unattractiveness, currency demand has continued to rise faster than money GDP in a number of countries (Fish and Whymark (2015)).

One interesting solution, then, would be to maintain the principle of a government-backed currency, but have it issued in an electronic rather than paper form. This would preserve the social convention of a state-issued unit of account and medium of exchange, albeit with currency now held in digital rather than physical wallets. But it would allow negative interest rates to be levied on currency easily and speedily, so relaxing the ZLB constraint.

Would such a monetary technology be feasible? In one sense, there is nothing new about digital, state-issued money. Bank deposits at the central bank are precisely that.

Here is a link to Alex Rosenberg’s distillation of his interview with me about negative interest rate policy (if you ignore the video at the top and focus on the words beneath that). He did a great job of representing our wide-ranging conversation in a compact way. (In the interview, I did give other economists, especially Willem Buiter, more credit for working out the key ideas for eliminating the zero lower bound than Alex indicated; it is a standard journalistic trope to simplify the story of collective efforts to make it sound like the work of one individual.)

I found one error, or at least misleading bit, in the article. It says:

At the same time, the government would have to remove the requirement that businesses accept cash as legal tender.

This is a common misconception about legal tender. For the most part, “legal tender” laws only affect the treatment of debt. Except perhaps in a few states, shopkeepers are legally allowed to refuse payment in cash. (On many plane flights I have been on recently, they have announced that they would only accept payment by credit or debit card, for example.)

Here is the explanation from the US Treasury website about legal tender (found with the help of my brother Chris Kimball):

The pertinent portion of law that applies to your question is the Coinage Act of 1965, specifically Section 31 U.S.C. 5103, entitled “Legal tender,” which states: “United States coins and currency (including Federal reserve notes and circulating notes of Federal reserve banks and national banks) are legal tender for all debts, public charges, taxes, and dues.”

This statute means that all United States money as identified above are a valid and legal offer of payment for debts when tendered to a creditor. There is, however, no Federal statute mandating that a private business, a person or an organization must accept currency or coins as for payment for goods and/or services. Private businesses are free to develop their own policies on whether or not to accept cash unless there is a State law which says otherwise. For example, a bus line may prohibit payment of fares in pennies or dollar bills. In addition, movie theaters, convenience stores and gas stations may refuse to accept large denomination currency (usually notes above $20) as a matter of policy.

This means that adjusting “legal tender” itself, while desirable, is less crucial for the type of policy I am recommending. The legal tender issue for debts can be handled by putting appropriate clauses in debt contracts, if lawyers wake up. For payments to the government, legal tender is also an issue, but I think once people started showing up at the IRS with suitcases full of cash, the government would quickly fix that loophole.

Update: In response to my questioning of this passage, Alex corrected it to “At the same time, the government could not require that businesses accept cash as legal tender.”

Here I would say that it is important that businesses not be required to accept cash as legal tender for large-ticket durables and investment goods; it causes less trouble if the government requires businesses to accept cash for goods that people typically use cash for now (indeed, I have argued that businesses might in any case voluntarily continue to accept cash at par for a long time even in the absence of any government constraint), and below-par cash as legal tender for debts, while an undesirable side effect, does not create a zero lower bound, since one cannot get an unlimited supply of new debt contracts on the same terms as old debt contracts.

Not. Image source

Because the government so often makes mistakes, good parents aplenty have been afraid of “Child Protective Services” taking their children away for no good reason. But John Stuart Mill argues for the appropriateness of at least some government intervention in parent-child relationships in paragraph 12 of On Liberty “Chapter V: Applications”:

I have already observed that, owing to the absence of any recognised general principles, liberty is often granted where it should be withheld, as well as withheld where it should be granted; and one of the cases in which, in the modern European world, the sentiment of liberty is the strongest, is a case where, in my view, it is altogether misplaced. A person should be free to do as he likes in his own concerns; but he ought not to be free to do as he likes in acting for another, under the pretext that the affairs of the other are his own affairs. The State, while it respects the liberty of each in what specially regards himself, is bound to maintain a vigilant control over his exercise of any power which it allows him to possess over others. This obligation is almost entirely disregarded in the case of the family relations, a case, in its direct influence on human happiness, more important than all others taken together. The almost despotic power of husbands over wives needs not be enlarged upon here, because nothing more is needed for the complete removal of the evil, than that wives should have the same rights, and should receive the protection of law in the same manner, as all other persons; and because, on this subject, the defenders of established injustice do not avail themselves of the plea of liberty, but stand forth openly as the champions of power. It is in the case of children, that misapplied notions of liberty are a real obstacle to the fulfilment by the State of its duties. One would almost think that a man’s children were supposed to be literally, and not metaphorically, a part of himself, so jealous is opinion of the smallest interference of law with his absolute and exclusive control over them; more jealous than of almost any interference with his own freedom of action: so much less do the generality of mankind value liberty than power. Consider, for example, the case of education. Is it not almost a self-evident axiom, that the State should require and compel the education, up to a certain standard, of every human being who is born its citizen? Yet who is there that is not afraid to recognise and assert this truth? Hardly any one indeed will deny that it is one of the most sacred duties of the parents (or, as law and usage now stand, the father), after summoning a human being into the world, to give to that being an education fitting him to perform his part well in life towards others and towards himself. But while this is unanimously declared to be the father’s duty, scarcely anybody, in this country, will bear to hear of obliging him to perform it. Instead of his being required to make any exertion or sacrifice for securing education to the child, it is left to his choice to accept it or not when it is provided gratis! It still remains unrecognised, that to bring a child into existence without a fair prospect of being able, not only to provide food for its body, but instruction and training for its mind, is a moral crime, both against the unfortunate offspring and against society; and that if the parent does not fulfil this obligation, the State ought to see it fulfilled, at the charge, as far as possible, of the parent.

I think the government policy questions here are quite hard. But on the much more basic question of whether it is appropriate for us to take an interest in the way other people treat their children, I would give a resounding “Yes!”

Even there, one should beware of the mistakes one could make because one has not walked in another parent’s shoes. Many a parent, after being blessed with an easy child for their first, and falling prey to a certain arrogance as a result, have been brought up short by how hard a time they had with a later child.

Nevertheless, at the end of the day, it is the children’s interests that must come first, not the parents’ interests. It is because it generally makes sense to trust parents to have a child’s interests more deeply at heart than the government that it makes sense to give parents the latitude society does give them. (A good illustration of an area where the government frequently does not have children’s interests very deeply at heart is where educational quality in the public schools comes into conflict with the interests of teachers.)

I love this video of a scale model of the solar system with Earth the size of a marble. It takes 7 miles in the desert to do it. Thanks to my brother Joseph Kimball for pointing me to the NPR article talking about this.

Look at the two dots below zero showing the idea that negative rates should start now and continue into 2016. Thanks to Leon Berkelmans for pointing this out.

Bleg: Do I need to change my title? Has this happened before?

For those who want to get some evidence of causality between awareness of how easy it is to break through the zero lower bound and leaning toward negative rates, see the schedule of my travels so far to talk about eliminating the zero lower bound here.

Eric Schlosser is most famous as the author of Fast Food Nation. I recently finished another of his books: Reefer Madness: Sex, Drugs and Cheap Labor in the American Black Market, which is about three sectors of the underground economy: drugs, undocumented workers, and pornography, all viewed from a business and public policy perspective. Here is Wikipedia’s current summary of its three chapters:

Chapter 1: Reefer Madness, Schlosser argues, based on usage, historical context, and consequences, for the decriminalization of marijuana.

Chapter 2: In the Strawberry Fields, he explores the exploitation of illegal immigrants as cheap labor, arguing that there should be better living arrangements and humane treatment of the illegal immigrants America is exploiting in the fields of California.

Chapter 3: An Empire of the Obscene details the history of pornography in American culture, starting with the eventual business magnate Reuben Sturman.

Here are three passages that I found especially interesting, including the historical origin of marijuana laws in xenophobia and how boring pornography can be:

Darwin’s Dangerous Idea has been one of the most influential books in my thinking and in my life. One of the most memorable examples in that book was Max Westenhoefer and the Alister Hardy’s “Aquatic Ape Hypothesis”: the idea that human beings are evolved for living on the seashore. The idea of being an “aquatic ape” resonates with me because I have always loved swimming and I love seeing ocean waves crash against a beach. Curtis Marean’s article “The Most Invasive Species of All” in the August 2015 issue of Scientific American touched on the Aquatic Ape Hypothesis. He writes on page 36:

Genetic and archaeological evidence suggests that H. sapiens underwent a population decline shortly after it originated, thanks to a global cooling phase that lasted from around 195,000 to 125,000 years ago. Seaside environments provided a dietary refuge for H. sapiens during the harsh glacial cycles that made edible plants and animals hard to find in inland ecosystems and were thus crucial to the survival of our species. These marine coastal resources also provided a reason for war. Recent experiments on the southern coast of Africa, led by Jan De Vynck of Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University in South Africa, show that shellfish beds can be extremely productive, yielding up to 4,500 calories per hour of foraging. My hypothesis, in essens, is that coastal foods were a dense, predictable and valuable food resource. As such, they triggered high levels of territorialisty among humans, and that territoriality led to intergroup conflict. This regular fighting between groups provided conditions that selected for prosocial behaviors within groups–working together to defend the shellfish beds and thereby maintain exclusive access to this precious resource–which subsequently spread throughout the population.

This is a very interesting column by Paul Krugman in his area of professional expertise.

Any unlimited opportunity to lend to the government at a zero interest rate creates a zero lower bound. In practice, when currency regions have gone to negative interest rates, as Switzerland, Denmark, Sweden and the euro zone have, they have lowered their interest rates on reserves, so it is the unlimited opportunity to lend to the government at a zero interest rate by withdrawing paper currency from the bank that seems to be the toughest issue.

The opportunity to lend to the government at a zero interest rate by prepaying taxes is another interesting issue. but as my brother Chris and I argued in “However Low Interest Rates Might Go, the IRS Will Never Act Like a Bank,” for the US at least, it is a limited one, unless the Secretary of Treasury intends to subvert the negative interest rate policy. Once one is paying all one’s taxes at the beginning of the tax year, there is no further available arbitrage on that front, since the between-year tax rate is by law supposed to be set by the Secretary of the Treasury in line with other short-term interest rates.

How can a central bank keep people from shifting their money into paper currency when interest rates are negative? The long answer can be found in all the links in my bibliographic post “How and Why to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound: A Reader’s Guide.” The short answer can be found in the CEPR’s 5-minute interview with me:

The basic idea depends on one of the roles of central banks that many “Money and Banking” textbooks fail to mention: the role of determining how much, among all the forms of money under its jurisdiction, each type is worth compared to the others. Let me use the example of Japan, since I thought about this issue in the context of writing “Is the Bank of Japan Succeeding in Its Goal of Raising Inflation?” and “Japan Should Be Trying Out a Next-Generation Monetary Policy” last week. Ultimately, it is not the numbers “10000” and “1000” written on them that make a ten-thousand-yen note equal in value to ten one-thousand-yen notes—it is the fact that the Bank of Japan is willing to freely convert a ten-thousand-yen note into ten one-thousand-yen notes and vice versa. Such conversions happen at a part of the central bank so underappreciated that some central bankers don’t even know where it is: the cash window.

It Isn’t the Face Value that Determines How Much Each Type of Paper Currency is Worth. To see this role of a central bank clearly, consider a case where not only direct access to the central bank, but access to the banking system in general is problematic: the criminal underworld. Think of the standard scene in American mob movies in which the mobster demands a suitcase full of cash in tens and twenties. Why tens and twenties? Using the banking system often increases the chance that a criminal will get caught. Money can be laundered, but it is easier to launder tens and twenties. So, at least near the point of money laundering, ten ten-dollar bills are worth more than one hard-to-launder hundred-dollar bill. That means that if you bring me a suitcase full of one-hundred dollar bills with the same face value as a suitcase full of tens and twenties, you are bringing me less value—you have cheated me.

The Exchange Rate Between Paper Currency and Electronic Money. Just as central banks determine the relative value of different denominations of paper currency by how they treat them at the cash window, they also determine how much paper currency is worth compared to electronic money in a reserve account by how they treat the paper currency at the cash window. A reserve account here is a private bank’s bank account with the central bank; for the Bank of Japan, the balance in a reserve account is a number in the Bank of Japan’s computer system. If the Bank of Japan treated a paper 1000-yen note as worth 990 electronic yen, that is what it would be worth. Here is what it means to treat a 1000-yen note as worth 990 electronic yen: (a) when a private bank came to the cash window of the Bank of Japan and hands in a paper 1000-yen note to have the money put into its reserve account the Bank of Japan would add only 990 yen to that private bank’s reserve account; (b) when a private bank came to the cash window of the Bank of Japan and asked for a paper 1000-yen note, only 990 yen would be deducted from its reserve account.

By the phrase “forms of money under its own jurisdiction” I mean forms of money that a central bank has the authority to print or otherwise create in unlimited quantities. If a central bank can create unlimited quantities of two forms of money, it can commit to exchange one form for the other at any exchange rate it declares without any reason to worry that it won’t be able to provide the form a bank wants to change another form of money under its authority into. In other words, the central bank has unlimited firepower for defending any exchange rate it declares between different forms of money under its jurisdiction. Moreover, an exchange of one form of money for another at a declared exchange rate does not, in itself, directly change the quantity of high-powered money under the central bank’s jurisdiction (though altering the exchange rate between different forms of money may).

To emphasize, a central bank can easily defend any exchange rate it declares between paper currency and electronic money–just as, say, the Fed can easily defend the exchange rate between $20 bills and $10 bills–since it has the authority to create as much of either one that banks want to change the other into.

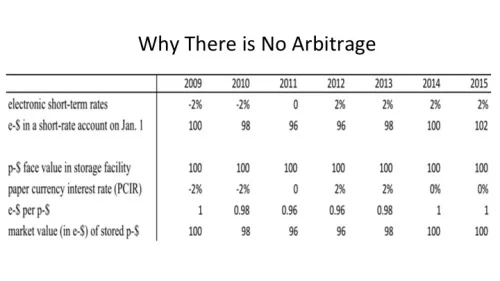

Using the Exchange Rate Between Paper Currency and Electronic Money to Create a Non-Zero Paper Currency Interest Rate. Once a central bank uses it power to determine the relative price of different forms of money under its jurisdiction in earnest, it is straightforward to insure that there is no way to circumvent negative interest rates by storing paper currency. Consider this slide from my presentation “18 Misconceptions about Eliminating the Zero Lower Bound”:

In this example contemplating an alternate history, the central bank has a -2% target rate for two years: 2009 and 2010. To get anything close to a -2% market equilibrium interest rate, the central bank must also reduce it interest rate on reserves to something close to zero. And it needs to reduce its paper currency interest rate to something closer to -2% than to 0. How can it do that? $100 will still have a $100 face value no matter how long it is stored (until cash physically disintegrates). But its market value is determined by how that paper currency with a face value of $100 is treated at the cash window of the central bank. If the central bank treats it as 100 electronic dollars on January 1, 2009, gradually decreasing to 98 electronic dollars on January 1, 2010, and to 96 electronic dollars on January 1, 2011, the rate of return of that paper currency will be -2% per year throughout 2009 and 2010. The idea is to match the paper currency interest rate to the target rate. (One could have a small spread relative to the target rate–say .5% in either direction without causing too much trouble, but the example is simplest if the target paper currency spread is zero.) To match the paper currency interest rate to the 0 target rate in 2011, the central bank need to treat the $100 face value worth of paper currency as $96 electronic throughout 2011. Then with the target rate equal to +2% per year in 2012 and 2013, the central bank can gradually bring the value of the $100 in face value of paper currency back up to being worth $100 electronic around January 1, 2014.

Where the Magic Is. How can an exchange rate between paper currency and electronic money avoid arbitrage without elaborate tracking of each paper note? It is because the rate of change of the exchange rate automatically keeps track of the cumulative paper currency interest rate over the time the paper currency is in private hands–and the paper currency interest rate (really a capital gains rate) is kept equal to the target rate. To reemphasize, it is not the level of the exchange rate between paper currency and electronic money that does the magic, but the rate of change. Just as a sundial keeps track of how much time has passed by how far the shadow has moved, the exchange rate between paper currency and electronic money keeps track of the cumulative interest on paper currency by how far it has moved.

We are used to thinking of each central bank as having one currency. But it is quite possible for a single institution to supervise more than one currency. I explore the possibilities of a possibility that changes an international exchange rate in conjunction with the exchange rate between paper currency and electronic money in my column “How the Electronic Deutsche Mark Can Save Europe.” The reintroduction of a paper Deutsche Mark would be likely to create immediate, serious problems. The introduction of a purely electronic German mark would work well. In general, when the straightjacket of a single currency becomes too tight, it causes fewer problems to split off a strong currency in electronic form, rather than splitting off a weak currency (as in the worry over Grexit and the reintroduction of the Greek drachma, narrowly averted for now).

This is Noah’s 13th guest religion post on supplysideliberal.com. Don’t miss Noah’s other guest religion posts!

Here is Noah:

The other day a good friend of mine killed himself. So I’ve been thinking a bit more about death lately.

For a long time, I’ve thought of death not as a single event, but a continuous process. Elements of your personality, your desires, your beliefs and habits–everything that makes you you–are constantly being altered by experience. An individual is like a ship that gets taken apart and rebuilt plank by plank, until it’s not clear when the old ship died and the new ship came to life. Life is experience, experience is change, and change is death.

This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Who wants to be preserved in amber? If you want to imagine how bizarre and inhuman that would be, just read “Daddy’s World” by Walter Jon Williams, or “The Wedding Album” by David Marusek.

We fear death because of inborn self-preservation instinct. We’re sad about the deaths of our friends and family because of the lost opportunity of interacting with them in the future, and–sometimes–because we feel frustrated that our friends and family didn’t get the chance to live as much as they should have. But death isn’t necessarily a bad thing–it’s an inevitable and natural thing. It’s what you and I are both experiencing right this moment.

Far worse, I’d argue, is a bad life.

We don’t know why people commit suicide (though we know factors that forecast it, and there are some theories). But it seems certain that for most suicidal people, life involves a great deal of either physical or psychological pain. That pain is a tragedy that is distinct from the tragedy of death itself.

We often see suicide as a mistake, at least when neither terminal illness nor extreme physical pain are involved. We certainly tell people it’s a mistake, in order to stop our friends and family from committing suicide. In fact, it probably is a mistake, from a rational-optimizing-agent economics-type point of view. I know firsthand that depression dramatically distorts people’s estimates of the probability of living a good life. I have no doubt that suicidal feelings (which are not quite the same as depression) create similar breakdowns of rationality. Things like cognitive behavioral therapy and narrative psychology are intended to help people be more rational and not make that big mistake.

But even though suicide is usually a big mistake doesn’t mean that it comes out of the blue. The psychological pain of suicidal people is obvious and undeniable. For some suicidals, the pain lasts for years or decades before it finally becomes too much. And I’d argue that it’s that pain that’s the biggest tragedy. Life is crueler than death.

As a society, we expend a lot of effort trying to stop people from committing suicide. When I searched on Google for reasons that people commit suicide, it sent me straight to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (Thanks, Google!). But we spend a lot less time and effort trying to alleviate people’s psychological pain long before they have suicidal ideation. As happens so often with our healthcare system, we ignore preventative medicine and focus entirely on crisis management.

This may be due to a lingering tendency of our society to downplay psychological pain. People who have never been depressed often regard depression as a choice. Deep down, many people probably regard depression and suicidal feelings as a weakness of will, or a manipulative plea for support and sympathy from others.

How many times have you heard some hippie barista in a coffee shop tell you that “Happiness is a choice?” That sounds cute, but it’s really just a modern hipster equivalent of a military commander slapping a soldier with PTSD and yelling at him to snap out of it. We seem to think that if someone doesn’t have a gun to his head right this minute, he’s not in big trouble.

Part of that is understandable. Psychological pain is much less visible than physical pain, and it also probably varies more from person to person. But part of our disdain for psychological pain probably comes from a lingering culture of personal toughness and responsibility.

This approach to psychological pain is not working. The U.S. suicide rate has soared by about 30 percent in recent years. The suicide prevention hotlines are not getting the job done, folks.

As for what we can do to eliminate psychological pain, I have some ideas. But those will have to wait for another time. The point I want to make today is that we need to stop thinking so much about the tragedy of death, and start thinking more about the tragedy of lives filled with psychological pain. Like Mel Gibson said in “Braveheart,” everyone dies, but not everyone truly lives.

“What is indoctrination and how is it different from regular instruction? Indoctrination, suggests Christina Hoff Summers, is characterized by three features, the major conclusions are assumed beforehand, rather than being open to question in the classroom; the conclusions are presented as part of a ‘unified set of beliefs’ that form a comprehensive worldview; and the system is ‘closed,’ committed to interpreting all new data in the light of the theory being affirmed.

Whether this account gives us sufficient conditions for indoctrination, and whether, so defined, all indoctrination is bad college pedagogy, may certainly be debated. According to these criteria, for example, all but the most philosophical and adventurous courses in neoclassical economics will count as indoctrination, since undergraduate students certainly are taught the major conclusions of that field as established truths which they are not to criticize from the perspective of any other theory or worldview; they are taught that these truths form a unitary way of seeing the world; and, especially where microeconomics is concerned, the data of human behavior are presented as seen through the lens of that theory. It is probably good that these conditions obtain at the undergraduate level, where one cannot simultaneously learn the ropes and criticize them–although one might hope that the undergraduate will pick up in other courses, for example courses in moral philosophy, the theoretical apparatus needed to raise critical questions about these foundations.”

– Martha Nussbaum, Cultivating Humanity: A Classical Defense of Reform in Liberal Education, p. 203.

Here is a link to my 66th column on Quartz, “Japan should be trying out a next-generation monetary policy.” My working title was “Japan is wasting its time trying to raise inflation.”

Monday’s post “Is the Bank of Japan Succeeding in Its Goal of Raising Inflation?” was written in conjunction with writing this column.

I often have occasion to say that I have presented my proposal for eliminating the zero lower bound all around the world. I give the full list of where I have given talks on eliminating the zero lower bound in “Electronic Money: The Powerpoint File.” To see how literal that statement can be taken, I wanted to tally up how many time zones I can account for, only counting presentations at central banks and their branches. I intend to keep this updated as I add additional time zones.

Here they are, in the order of sunrise on a particular calendar date, with the first date listed when I have been to more than one central bank or branch of a central bank in that time zone. Note that UTC 0 is the same as Greenwich Mean Time.

To put this in perspective, let me point out that some time zones are not as well provided with central banks and central bank branches as other time zones! But other time zones I hope to add soon.

My paper coauthored with Dan Benjamin, Ori Heffetz and Nichole Szembrot on how to build national well-being indices in a principled way is now available to the everyone free on PubMed at the link above.