John Stuart Mill on Humans vs. the Lesser Robots

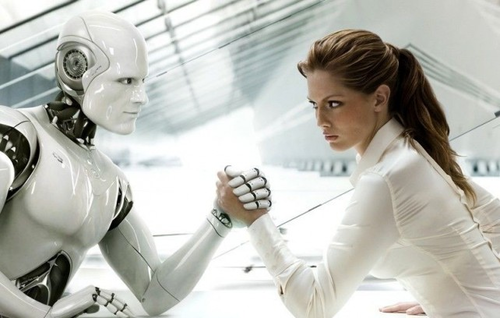

Someday robots will have great moral worth of their own as conscious beings. But there is another image of robots in our culture as something distinctly less than human: emotionless, stilted, doing routine things by rote. Just think of the connotations of the word “robotic,” when applied to humans. So among robots, let me distinguish between

- androids–the higher robots who are like us, only different, and

- automatons–lesser robots that are distinctly less than human.

Part of John Stuart Mill’s argument for freedom urges us to strive to elevate ourselves far above the level of these lesser robots. He never uses the word “robot,” since that word only entered the English language in 1923, in the English translation of a 1920 Czech play by Karel Capek. But John did use the word “automaton,” in exactly the sense I just defined. Here is what he has to say in On Liberty, chapter III, “Of Individuality, as One of the Elements of Well-Being,” paragraph 4:

He who lets the world, or his own portion of it, choose his plan of life for him, has no need of any other faculty than the ape-like one of imitation. He who chooses his plan for himself, employs all his faculties. He must use observation to see, reasoning and judgment to foresee, activity to gather materials for decision, discrimination to decide, and when he has decided, firmness and self-control to hold to his deliberate decision. And these qualities he requires and exercises exactly in proportion as the part of his conduct which he determines according to his own judgment and feelings is a large one. It is possible that he might be guided in some good path, and kept out of harm’s way, without any of these things. But what will be his comparative worth as a human being? It really is of importance, not only what men do, but also what manner of men they are that do it. Among the works of man, which human life is rightly employed in perfecting and beautifying, the first in importance surely is man himself. Supposing it were possible to get houses built, corn grown, battles fought, causes tried, and even churches erected and prayers said, by machinery—by automatons in human form—it would be a considerable loss to exchange for these automatons even the men and women who at present inhabit the more civilized parts of the world, and who assuredly are but starved specimens of what nature can and will produce.

There is power in large groups of human beings acting in concert. But when that concerted effort is enforced by making each one of those human beings less–a little like an automaton–then the power is greatly reduced. There is greater power in a large group of human beings acting in concert when each individual is acting with the full capacity that comes from freedom.