On Barry Schwarz's `The Paradox of Choice'

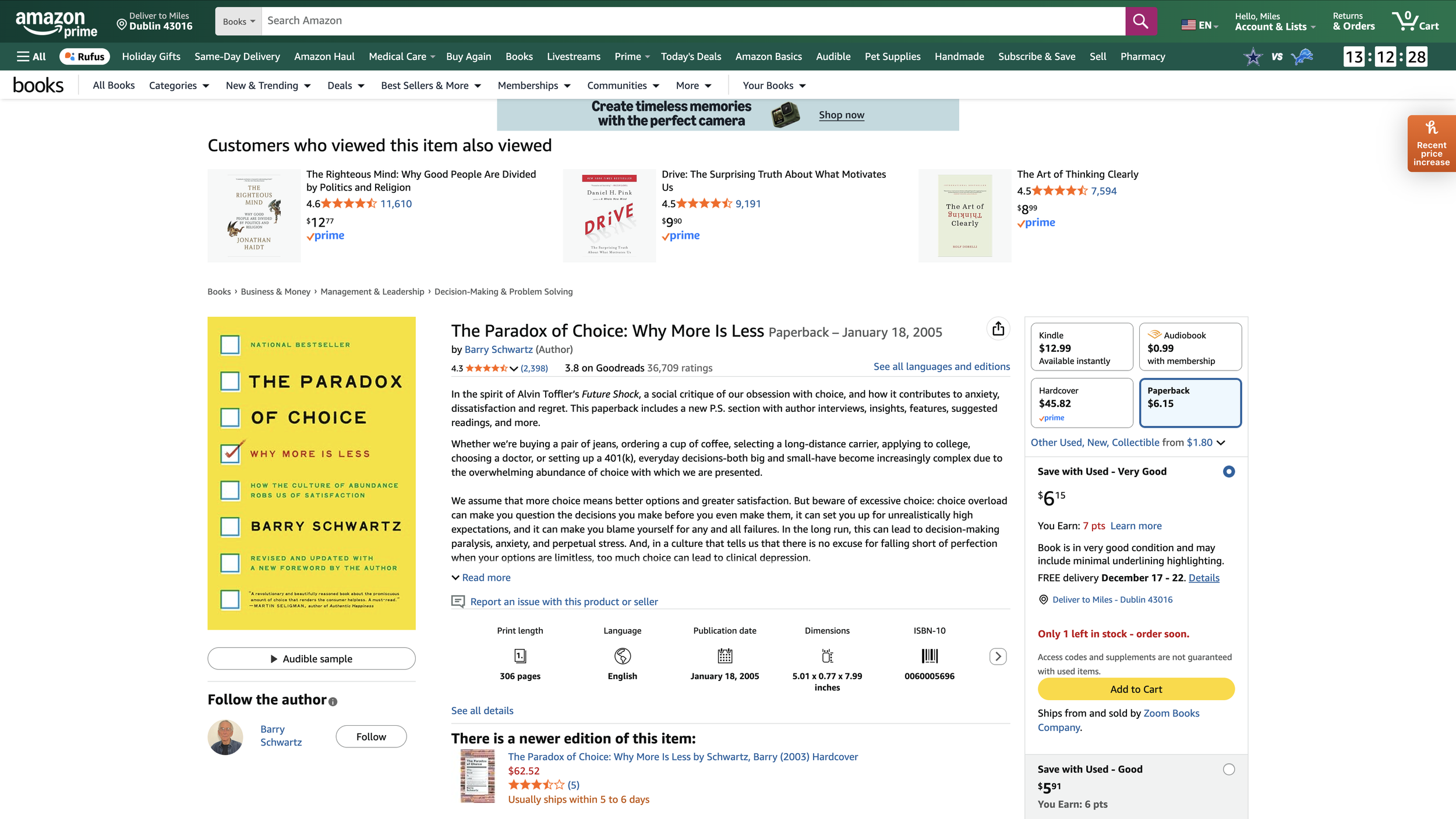

Link to the Amazon page for The Paradox of Choice by Barry Schwarz

As an economist, I have long been annoyed. Contrary to “Having fewer choices is better” message many readers are likely to get from the book, more choices are always better, as long as (a) information is not destroyed and (b) you aren’t stupid about dealing with a larger number of choices.

On destruction of information, consider a website for a type of product you are purchasing for the first time where—instead of the best three options appearing on the landing page—here are now ten options. You now have less guidance than before. By contrast, if what are usually the best three options appear on the main page, and there is a button for “more options” that you ignore unless you really dislike the three main options, you are better off. (Of course, another way destroy information is for the website to steer you to products other that what are usually the best three. Commercial interests don’t always match up with yours. That topic deserves its own post. Some companies do pursue a business model dependent on customers trusting them; this example works best for such a website.)

On not being stupid, it is important to realize that the goal is not “the best product”, but having a good life. In the example agove, ignoring the additional options behind the “more options” button unless you really dislike the three main options is important. Time and attention are some of your scarcest resources. You need to be careful to economize on them. Tim Ferris’s post, “The Choice-Minimal Lifestyle: 6 Formulas for More Output and Less Overwhelm” explains how not to be stupid. He writes:

1) Considering options costs attention that then can’t be spent on action or present-state awareness.

2) Attention is necessary for not only productivity but appreciation.

and gives a lot of good practical advice.

Tim’s advice is based on good economics. It is stupid to ignore information processing costs. The principles of economics require taking information processing costs into account just as much as any other type of costs.

The reason people may think taking information processing costs into account is contrary to economics is because economists aren’t yet very good at modeling how to deal with information processing costs—that is, how to make good decisions about how hard to think about decisions. If I were to propose one problem for microeconomic theory that would be like the Millenium Prize Problems for mathematics, it would be to figure out a way of modeling information processing costs so attractive that it is routinely taught in the core microeconomic theory courses of Economics PhD programs and is routinely used by economists to model whatever applied problem they are studying. This is a hard problem, for reasons I lay out in my post and paper “Cognitive Economics.” 75 years ago, modeling imperfect information and modeling imperfect information processing would have seemed like similar problems. They aren’t. In 2025, modeling imperfect information is essentially a solved problem. But we still have only half-baked models for imperfect information processing. As we stand in 2025, modeling imperfect information processing well is now the holy grail for microeconomic theory.