What Bond Risk Premia Mean for Monetary Policy

Without a big staff to help me crunch numbers, in monetary policy recommendations, I have been trying to stick to easy judgments, like my recommendation that the ECB immediately cut its target rate to -2%, making the necessary adjustments in paper currency policy.

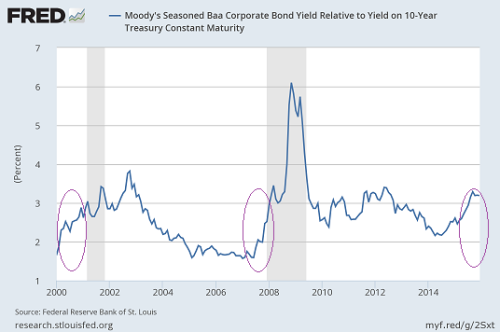

One other easy judgment is to say that a central bank’s target rate should routinely–and fairly mechanically–respond to risk premia in the bond market. To be more specific, the Fed should offset something like 80% of any rise in credit spreads like the one shown above between the 10-year corporate Baa rate relative to the 10-year Treasury bond rate. The basic reason is that the rate at which companies can borrow is crucial to the levels of investment that drive the business cycle. So it makes sense to keep corporate borrowing rates and wholesale commercial rates in a good range. To spell out what I mean by saying the adjustment for risk premia should be done “fairly mechanically,” I recommend that central banks state their target short-term safe rates (such as the Fed funds rate or the repo rate) not as a number, but as a number minus .8 times a suitable credit spread so that the adjustment would take place automatically even in between meetings of the monetary policy committee.

I wrote about this issue before in my column “Meet the Fed’s New Intellectual Powerhouse”:

Too much discussion of monetary policy has proceeded under the fiction that there is only one interest rate. As soon as one recognizes that there are as many different interest rates as there are types of assets, an obvious question arises: “Which interest rates give the best idea of the cost of borrowing for the home-building, consumer spending, and business investment that drive aggregate demand for the economy?” The obvious—and correct—answer is that it is rates for mortgages, consumer loans, and loans to businesses (of which the lending represented by corporate bonds is an important part) that best represent the borrowing costs that matter for aggregate demand.

So even when the Fed states its policy in terms of the safe fed funds rate, it should be looking past that safe rate to the mortgage rates, consumer-loan rates, and corporate borrowing rates that result. Even before considering the risk of a financial crisis, the Fed should react to an increase in bond risk premiums almost one-for-one by a reduction in the safe rate, and should react to a narrowing of bond risk premiums almost one-for-one by an increase in the safe rate. (The reason I write “almost” one-for-one is that the risk premium has an effect on savers as well as on borrowers, but evidence suggests that savers are not very sensitive to interest rates, so it is the effect of the key rates on borrowers that is of greatest concern.)

This principle is one that shows up in formal models and simulations of optimal monetary policy. See for example Vasco Curdia and Michael Woodford’s, “Credit Spreads and Monetary Policy.” As I said as a conference discussant of their related paper, I think Vasco Curdia and Michael Woodford understate the extent to which a central bank should offset credit spreads, since they do not adequately account for how much more sensitive borrowing is to interest rates than lending is. (You can see the Powerpoint file for my discussion here.) In any case, it would be a significant mistake for a central bank not to offset more than half of a measure of credit spreads by cutting the safe government rate when the spread between safe government rates and corporate rates goes up. Above I suggested offsetting 80% of any rise in credit spreads by a fall in the target rate, but this number should be carefully studied in formal models of optimal monetary policy. The right number may easily be closer to 90%. When I say “studied in formal models of optimal monetary policy” it should be obvious that a quantitative answer worth taking seriously can only come out of a model that explicitly models investment, not from a model with only nondurable consumption.

From the graph at the top, you can see that this point is one highly relevant to the current situation. To the extent the Fed and other central banks don’t have credit spreads fully built into the rules of thumb they use for monetary policy–or into more formal models of optimal monetary policy used for practical purposes, their interest rate decisions may be off target.

Although it is not 100% clear to me that the Fed has the wrong interest rate at the moment, I worry a lot that if news comes in that makes a lower interest rate the right thing to do that the members of the FOMC making decisions on interest rates will be slow to respond to that news by cutting rates. One of the more dangerous notions about monetary policy is that a central bank must by all accounts avoid losing face by reversing course on interest rate changes. (See my more detailed discussion here.) Following that twisted logic, the fact that the Fed raised rates once a few months ago would mean that it would not allow itself to cut rates again until the situation became truly dire–with all the costs to the economy that would ensue from not acting more promptly. It is crucial that the policy-makers at the Fed begin putting to rest the idea that reversing course is a terrible thing. Which makes more sense: responding promptly to news, or not responding promptly to news?