Jonathan Zimmermann: Making College Rankings More Useful

One way in which my own industry of higher education is corrupt is in resisting the data collection and sharing that would allow full evaluation of how well each college or university is doing its teaching job. A special report by the March 28-April 3 2015 issue of the Economist emphasizes the importance of better data for evaluating colleges and universities in order to put the higher education system on a path for significant improvement in performance. Within the special report, the article “A flagging model” is especially worth reading. Here are three of my favorite passages:

1. In most markets, the combination of technological progress and competition pushes price down and quality up. But the technological revolution that has upended other parts of the information industry (see article) has left most of the higher-education business unmoved. Why?

For one thing, while research impact is easy to gauge, educational impact is not. There are no reliable national measures of what different universities’ graduates have learned, nor data on what they earn, so there is no way of assessing which universities are doing the educational side of their job well.

2. The peculiar way in which universities are managed contributes to their failure to respond to market pressures. “Shared governance”, which gives power to faculty, limits managers’ ability to manage. “It was thought an affront to academic freedom when I suggested all departments should have the same computer vendor,” says Larry Summers, a former Harvard president. Universities “have the characteristics of a workers’ co-op. They expand slowly, they are not especially focused on those they serve, and they are run for the comfort of the faculty.”

3. Better information about the returns to education would make heavy-handed regulation unnecessary. There is a bit more around, these days, but it is patchy. The CLA has been used by around 700 colleges to test what students have learned; some institutions are taking it up because, at a time of grade inflation, it offers employers an externally verified assessment of students’ brainpower. Payscale publishes data on graduates’ average income levels, but they are based on self-reporting and limited samples. Several states have applied to the IRS to get data on earnings, but have been turned down. The government is developing a “scorecard” of universities, but it seems unlikely to include earnings data. “A combined effort by the White House, the Council of Economic Advisers and the Office of Management and Budget is needed,” says Mark Schneider, a former commissioner of the National Centre for Education Statistics. It is unlikely to be forthcoming. Republicans object on privacy grounds (even though no personal information would be published); Democrats, who rely on the educational establishment for support, resist publication of the data because the universities do.

Jonathan Zimmermann, from my “Monetary and Financial Theory” class this past Winter 2015 semester discusses very well the need for different college rankings for different purposes. This is the 20th student guest post from this past semester. You can see the rest here, including two by Jonathan himself. Here is Jonathan’s latest:

For every student who has been through the process of college admission, university rankings is something that should look familiar. But university rankings are not only used by prospective students, they are also consulted by employers to screen job candidates.

Increasingly, it becomes a trend for every well recognized newspaper to publish its own ranking. Currently, universities and colleges are mostly ranked with some positive weight on how good the students are at the end of college and some weight on how good the students are at the beginning of college before they have started any classes. This is not what students need to know. What students need to know is how much they will learn – that is how good they will be at the end of college minus how good they are at the beginning. And if students really learn a lot, i.e. if they are much better at the end of college than they were at the beginning, they really need the college or university to document how good they are at the end in a way that is persuasive to employers.

This is very different from the way things are done now. The cost of the program, for example, is only relevant to the prospective student: the potential employer should not care about how much the student paid but only about the quality of the formation, even if the costs were totally disproportionate (which would, in the other hand, reduce the ranking of the university in a ranking designed for students). In the contrary, a university that is well known to only accept already very clever and experienced students (students with already a good GPA, a previous degree in another top ranked college, etc.) should have a lower ranking on student-oriented rankings since they don’t bring much to the students they admit, but should have a good ranking on employer-oriented rankings because they tend to do a pretty good job at screening candidates. Of course, graduating from a program well ranked in employer-oriented rankings is also an advantage for students since it will ease their job search (like purchasing a “certificate of competence” would), but it is far from as valuable to them as it is to employers, and represents only a small fraction of the advantages of college education, compared notably to the “learning component”.

Rankings such as those of the Financial Times tend to generate that kind of negative incentives for the universities by giving a lot of weight to the salary and the employment rate after graduation: if you know that this is how your program is going to be ranked, as the admission director you might decide to only take students who already have a job secured, or at least strong connections in the professional world, instead of a bit more risky profiles who could really use the knowledge and experience your program would bring them.

In general, everything that increases the predictive value of the degree is important to the recruiters. And this doesn’t only include the binary fact of having the degree or not having the degree, but also the predictive value of the GPA associated with the degree. And this is an extremely important element that is neglected by almost every ranking, but that also hurts some countries much more than others.

The United States for example are very well known for having a very rigorous admission process. But once you made your way into an Ivy League, the GPA you get is of secondary importance (a problem aggravated by the severe trend of grade inflation). This should factor in the employer-oriented rankings, since they cannot efficiently use elements such as the GPA to screen their candidates. On the other hand, countries like Switzerland which are much more generous in admitting students (even the best universities of the country, such as ETH Zurich which is consistently ranked among the top 20 universities in the world, accept almost 100% of their candidates, sometimes even without a high-school degree) and giving degrees (even though the failure rate during the first year is extremely high to compensate for the eased admission) rely much more on the grades that they attribute to indicate to the market who are the good students and who aren’t. This should indeed be reflected negatively in the rankings designed to help students decide where to go once admitted (since being admitted in that kind of university is not even one tenth of the way), but very positively into employer-oriented rankings since they can easily identify good students by looking at their grades.

The problem with current rankings is that they are used indifferently. Some are more prospective students oriented, some are more employers oriented, many are research oriented (which creates other forms of negative incentives), but the distinction is generally not made and, frequently, both criteria are mixed. Each ranking should not only be designed with a clear purpose in mind, but should also clearly communicate that purpose to its readers. Clearly, simply stating the methodology used is insufficient: not only it generally uses complex math that most readers don’t have the time (or the ability) to understand, but it also doesn’t indicate when it is appropriate to use it. Instead, the rankings should be accompanied with qualitative advices to interpret the results as well as a list of contexts in which the ranking is considered relevant or not, their strengths and its limitations, and especially who the target audience is.

The college ranking currently designed by the Obama administration, for example, does an exemplary job in clearly stating the objectives of its methodology from the very beginning: helping prospective students with medium to low income to identify colleges with the best quality-to-price ratio. Nothing more, nothing less; it doesn’t have the ambition to become the next universal university ranking, and therefore doesn’t mix its primary goal with other contradictory considerations.

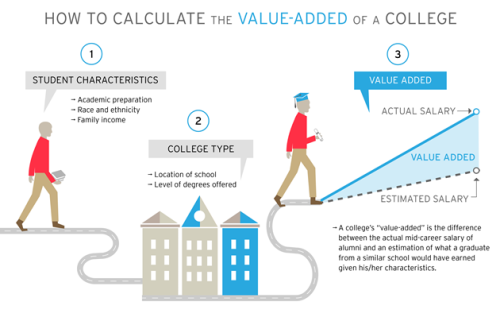

In general, most rankings designed for students should switch to a “value-added” approach, which measures the causal impact of college on students given their pre-education characteristics. One of the most up-to-date and accurate study using this method is the recently published “Beyond College Rankings” report; the methodology they use could serve as a model for further rankings. However, the problem with “value-added” rankings is that they are of limited use when they are not “dynamic”. Traditional rankings are “static” in the sense that every university in the same ranking will always have the same rank independently from the person reading it. A “static value-added” ranking is useful to governments and charities seeking to allocate their funds to the most efficient institution, but generally not adequate for individuals since the essence of a “value-added” ranking is to provide a list of best colleges given a specific student’s characteristics. A clever value-added ranking designed for students would allow them to input their personal characteristics before providing them with a personalized result; the best choice of college might not be the same for two distinct students with a different profile.