The Consequences of Overly Strong Incentives: Wells Fargo, Baseball Baptisms, and Academic Advancement

This recent news about Wells Fargo (see for example Wells Fargo Warned Workers Against Sham Accounts, but ‘They Needed a Paycheck’) shows how overly strong incentives can cause people to cheat–especially if some of the higher-ups are OK with the cheating. Similar problems have occurred when teacher’s careers depend critically on student test scores.

Even in a religious context, the same danger of overly strong incentives leading to cheating in the sense of low-quality production can be a problem. In particular, the recent news about Wells Fargo reminded me of the “Baseball Baptism” era in Mormon proselyting when young men were acceptance Mormon baptism primarily because it was a requirement for belonging to a sports team. In the words of Michael Quinn in the article linked above:

… disadvantaged children and teen-agers may be eager to be dunked under water as the only requirement for a free trip to the beach or for membership in a sports club sponsored by a church.

Why would missionaries pursue such a course when people accepting baptism on such terms are unlikely to remain participating members of the Mormon Church for long? Here is Michael Quinn’s answer:

In the I-It relationship, performing baptisms is also a means for the missionary to gain something earthly. The missionary may want the praise of family and Church leaders for adding converts to the faith. Some missionaries use convert as a way to gain the personal “testimony” of the gospel that was absent in their pre-mission experience. The missionary may seek a sense of self-worth through baptizing others. Missionaries may believe that their eternal glory grows with each new convert. They may think that God’s love for them increases with each person they bring into his kingdom. The missionary may expect that performing more baptisms will increase the chances of advancement in Church office. The missionary may enjoy the “rush of competing with other missionaries to see who can baptize the most persons or which mission can "out-baptize” the other missions of the world. And-again in the main subject of this essay-Church leaders may put such intense pressures of reward or disfavor on a missionary’s baptismal numbers that young missionaries will do anything–anything–to satisfy those demands. In all of the above examples of I-It missionary work, potential converts and actual converts are only objects to fulfill the various goals of a missionary That is true whether a missionary’s I-It emphasis results in a single baptism or in thousands.

In “The Message of Mormonism for Atheists Who Want to Stay Atheists” I emphasized the motive of advancement in rank–a motive whose strength is hard to understand without a little more background:

While on a mission, missionaries are urged to work even harder to “get a testimony”—subjective spiritual experiences that will convince them the Mormon Church is true. In addition, they are motivated to work hard by a system of promotions in rank no doubt devised by one of the many middle-aged businessmen who take three years off from a regular job to serve as a “Mission President”–the head of a group of 150 or so young missionaries in a particular region. Mormon missionaries always travel in twos, so they can keep each other from getting into trouble–and in other countries to make sure that one of them has been there long enough to be able to speak the language reasonably well. A missionary starts out as a junior companion. It is a big day when a missionary finally makes it to being a senior companion. Later on, the missionary can hope to be promoted to District leader over three to seven other missionaries, to a Zone leader over, say, nineteen, and maybe even to being an assistant to the Mission President. It is hard to communicate how much we as missionaries cared about those promotions. And of course, there could be demotions in the form of being exiled to a remote district where it was especially hard to make converts.

The Mission Presidents, who, as I mentioned, often have business experience, also devise many other motivational strategies akin to those in the world of sales.

I greatly admire Michael Quinn as a historian who has done so much to illuminate Mormon history–even against the wishes of Mormon church leaders. I heard him present his work on the Baseball Baptism Era at a Sunstone Symposium. (Sunstone is an independent magazine about Mormonism that many Mormon church leaders wish didn’t exist. The Sunstone organization also puts on conferences.) I told of a phenomenon similar to Baseball Baptisms that occurred in the Tokyo South Mission of the Mormon Church while I was a missionary in the neighboring, but much more sedate Tokyo North Mission from 1979-1981. Here is how Michael Quinn wrote that up:

Was the baseball baptism era an unparalleled aberration in Mormon experience? Not from what a number of more recent LDS missionaries have told me. Most of the “well-known salesmanship techniques” remained in the missionary lessons and program. …

Early in 1980, a mission president in Japan used lavish dinners and other rewards as “incentives” for missionaries to reach baptism goals. The mission abbreviated the lesson-plan so that missionaries spent no more than an hour with “investigators” before baptizing them. This program was “encouraged by the general authority who was acting as an area president without counselors.” Presidency counselor Gordon B. Hinckley asked missionaries about these developments just before the dedication of the Tokyo temple that October. He ended the program by reinstituting the requirement for persons to attend at least one LDS meeting before baptism.

I was Gordon B. Hinckley’s main missionary informant about this, since when my grandfather Spencer W. Kimball–then the head of the Mormon Church–came to dedicate the new Tokyo Temple, I was invited (along with my missionary companion–we always did everything in pairs) to spend a few days away from my regular missionary duties to accompany him and my grandmother Camilla Eyring Kimball. That also put me in close contact with Gordon B. Hinckley. I remember Gordon Hinckley’s talk to the missionaries saying that conversion involved not only believing the doctrine of Mormonism but also “a decision to throw in their lot with us.” In addition imposing the requirement of attending at least one church meeting before baptism, Gordon B. Hinckley urged that “investigators” read his brief history of the Mormon Church: Truth Restored.

Even after that, at the time my 2-year missionary service was over, things baptisms of a sort were still coming thick and fast in the Tokyo South mission. My brother Jordan came to meet me and I had the chance to tour Japan a bit. One of the things we did was to visit a classmate of mine from Harvard who was serving in the Tokyo South mission. I saw the makeshift baptismal font set up in a missionary apartment. I got a copy of their very abbreviated lesson plan and heard about how they often represented baptism as part of joining a cool club.

During my mission, I was a bit envious of the much better statistics we heard about from the Tokyo South mission. But in retrospect, I was very grateful that I had a Mission President with more integrity than that: Michael Roberts.

The Moral of the Story:

I no longer believe in the supernatural or in Mormonism, but the lessons of the Baseball Baptism Era apply to many areas of life: in a large organization, there is a limit to how strong incentives providing extrinsic motivation can be without causing widespread cheating (in the sense of low-quality production that seems to answer the quantitative goals but does not truly meet the underlying goals very well). For economists and businesspeople who are trained to believe in incentives, this is a sad message, but an important one.

Formal competitions sometimes keep cheating down by extremely intensive monitoring. But monitoring as intensive as, say the referees on the field in a sports arena, along with all the watching fans scrutinizing things, can be expensive and not always easy to adapt to routine production.

The rewards for publishing journal articles are large enough to cause a certain amount of cheating even though the quality of articles can be monitored relatively thoroughly. Sometimes the cheating is in claiming data that doesn’t exist. Sometimes it is in mischaracterizing the statistical results–especially not mentioning all the failed experiments. Sometimes it is in saying something that sounds good but is misleading. Given all the many ways to cheat a little or a lot in the academic arena, we should be careful about judging our fellow academics on grounds that are too narrowly quantitative. A judgement about someone’s academic integrity and whether they are really trying to advance knowledge and make the world a better place should always be formed along with the counting of the beans (an apt metaphor for the counting of journal articles someone has published). It is possible for a bad person to have a brilliant scientific insight that one should take very seriously and build on. But a bad person who has done some good science needs to be watched very closely in case they slip in bad science along with the good.

On the other hand, someone who, with integrity is working hard to do the best that she or he can to advance knowledge and make the world a better place by applying knowledge should feel good about that even if her or his number of beans doesn’t add up to the same magnificent-looking pile as some others. Although occasionally, something wrong is like sand in an oyster and causes many other researchers to generate pearls of wisdom in reaction, in general, it is much better to have a short Curriculum Vitae with one scientific result that is right than a long Curriculum Vitae with one scientific result that is right and ninety-nine other misleading bits of supposed science.

Henry George on How Statistical Identification Problems Increase the Importance of Theory

“Thus the facts we must use and the principles we must apply are common facts that are known to all and principles that are recognized in every-day life. Starting from premises as to which there can be no dispute, we have only to be careful as to our steps in order to reach conclusions of which we may feel sure. We cannot experiment with communities as the chemist can with material substances, or as the physiologist can with animals. Nor can we find nations so alike in all other respects that we can safely attribute any difference in their conditions to the presence or absence of a single cause without first assuring ourselves of the tendency of that cause. But the imagination puts at our command a method of investigating economic problems which is within certain limits hardly less useful than actual experiment. We may test the working of known principles by mentally separating, combining or eliminating conditions.”

Henry George, Protection or Free Trade.

Judy Shelton Off-the-Mark on Monetary Policy

In an October 11, 2016 Wall Street Journal op-ed, Judy Shelton manages to be wrong on many counts about monetary policy, but wrong in an instructive way. Let me answer her points.

First, Judy does helpfully quote Maury Obstfeld and Christine Lagarde–both of whom are exactly right. Maury points out the political consequences insufficiently stimulative monetary policy among other economic problems:

… as IMF chief economist Maurice Obstfeld recently told the press, the problem has to do with the political consequences of sluggish economic performance. “In short, growth has been too low for too long,” he said, “and in many countries its benefits have reached too few, with political repercussions that are likely to depress global growth further.”

Christine Lagarde is exactly right in pointing out the monetary policy can do more. In particular, negative interest rate policy is still in its infancy, and could go a lot further:

In a Sept. 28 speech at Northwestern University, IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde dismissed as “pessimists” those who think central banks are not stimulating economic growth. “In my view, there is more policy space—more room to act—than is commonly believed,” she declared. “Monetary policy in advanced economies needs to remain expansive at this stage.”

Having just returned from visiting the Bank of Japan (where I communicated the message of my advice in “The Bank of Japan Renews Its Commitment to Do Whatever it Takes” with this Powerpoint file–pdf download), the Bank of Thailand, Bank Indonesia and the Bank of Korea in the past two weeks, I am headed at the beginning of next month on a tour of European central banks to try to expand the set of options European central banks are actively thinking about. Copying over from the cumulative itinerary I keep updating in my post “Electronic Money: The Powerpoint File”:

- Sveriges Riksbank (Stockholm), October 31-November 1, 2016

- Austrian National Bank November 2-4, 2016

- Bank of Israel, November 7-8, 2016

- Brussels Conference on “What is the impact of negative interest rates on Europe’s financial system? How do we get back?” sponsored by the European Capital Markets and Institute (ECMI), the Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) and the Brevan Howard Centre for Financial Analysis, November 9, 2016

- Czech National Bank, November 10-11, 2016

- European Central Bank, November 14-16, 2016

- Bank of International Settlements, November 17, 2016

- Swiss National Bank, November 18

1. Besides rejecting Maury’s and Christine’s sage words, Judy’s first mistake is to assume, that low interest rates exacerbate inequality. Judy writes:

The monetary policies enacted by the world’s leading central banks are a predominant mechanism for doling out differential financial rewards—exacerbating income inequality in the process. The Federal Reserve’s ultralow interest rates, intended to stimulate economic growth, have flooded wealthy investors and corporate borrowers with cheap money, while savers with ordinary bank accounts have been obliged to accept next-to-nothing returns.

Judy does have company in this mistake:

British Prime Minister Theresa May took on her own nation’s central bank in an Oct. 5 speech at her Conservative Party’s annual conference. “People with assets have got richer,” she said. “People without them have suffered. People with mortgages have found their debts cheaper. People with savings have found themselves poorer.”

The problem with this view is that there is strong, mechanical tendency for those who are lending to have a higher net worth than those who are borrowing. Thus, if low interest rates hurt lenders and help borrowers, it seems much more likely that this reduces inequality. And many of those who are wealthy and yet are borrowing in a big way are the entrepreneurs and firms investing in factories, software and R&D that are so important to the progress of an economy. And many firms borrow with long-term corporate bonds that commit to levels of coupon payments that don’t immediately change with fluctuations in short-term interest rates. It is true that lucky homeowners contribute a great deal to inequality, but leaving aside the travesty of the Great Inflation of the 1970′s, this has had at least as much to do with capital gains in markets where construction is overly restricted as to interest rate fluctuations.

2. Donald Trump is a little more on target in identifying those hurt by low rates–not those who are especially poor, but those who have been big savers who don’t like risk:

Mr. Trump readily admits that, as a developer, he likes low interest rates; at the same time, he recognizes that others have been penalized by the Fed’s monetary-policy decisions. As he said in a Sept. 12 CNBC interview: “The people that were hurt the worst are people that saved their money all their lives and thought they would live off their interest, and those people are getting just absolutely creamed.”

But this statement is still wrong, because it overestimates the power of the Fed and other central banks. In particular, the idea that central banks can initiate higher rates and keep them permanently higher is a myth exaggerating the power of central banks. In “Mark Carney: Central Banks are Being Forced Into Low Interest Rates by the Supply Side Situation” I talk about Bank of England chief Mark Carney’s eloquent explanation of how central banks must take as given what the natural rate of interest is. If they keep interest rates higher than that natural rate, it will hurt an economy badly, which will probably require lower rates to fix. Mario Draghi said something similar and similarly true, as I lay out in “Mario Draghi Reminds Everyone that Central Banks Do Not Determine the Medium-Run Natural Interest Rate.”

Central bankers are just making false excuses if they ever say they can’t stimulate more. But in the current environment, it is the truth when they say that the natural rate is low enough that they can’t stimulate effectively without having shockingly low rates.

Somewhat paradoxically, the only time central banks are to blame for persistently low rates is if they have previously failed to make rates low enough. Because the Fed did not have a -6% rate back in 2009 as the Taylor rule would have recommended, the Great Recession dragged on, and zero rates persisted for seven years, 2009–2015, with very low rates in 2016 as well. Moreover, because no central bank in modern times has yet demonstrated a willingness to use deep negative rates, or to have even a small nonzero paper currency interest rate, the markets factor in the chance of a continuing slump up against a lower bound on interest rates. Demonstrating clearly that central banks have and are potentially willing to use much, much more ammunition if needed would do a lot to allay this fear and thereby possibly bring up long-term rates.

3. It is interesting judging Judy’s statement that

… unconventional monetary policy has failed to deliver the anticipated boost to growth.

I suspect that, whatever the brave face they put on in public in order to maximize positive expectations, central bankers were always quite uncertain about how big the effect of quantitative easing would be. Since the simplest optimizing theories say that quantitative easing has no stimulative effect at all, the actual effect of quantitative easing was always going to depend on mechanisms that were not well understood. So anyone sensible would have had a large standard error on their estimate of the likely effective of quantitative easing. And similarly, there is reason for a large standard error on any estimate of the undesirable side effects of quantitative easing–particularly at dosages that higher than those that have been used so far.

By contrast, simple theories say that negative real rates should have essentially the same effect regardless of whether they come from high rates of inflation or from nominal rates. So “anticipated boost to growth” is a much more tightly defined phrase in relation to negative interest rates. But we know that responding to a recession historically requires something like a 5 or 6 percentage point reduction in short-term interest rates to get historical norms of recovery speed. And presumably a major financial crisis like that toward the end of 2008, after having been allowed to fester, could easily require a bigger reduction in rates to offset by monetary policy.

Given the moderate negative rates so far, relatively well-established numbers for the effect of interest rate cuts would not suggest any bigger an impact than we have seen from negative rates. And as I point out in “If a Central Bank Cuts All of Its Interest Rates, Including the Paper Currency Interest Rate, Negative Interest Rates are a Much Fiercer Animal,” historical norms of the effect of interest rate cuts apply, strictly speaking, only when the paper currency interest rate is kept in line or below other interest rates.

4. Judy’s assertion

… the Fed’s large-scale interventions in credit and investment markets have created significant distortions that threaten financial stability. We can’t expect Main Street to passively absorb the costs of a future Wall Street bailout; there is a limit to public patience with monetary policy that not only smacks of favoritism but might also be causing more harm than good.

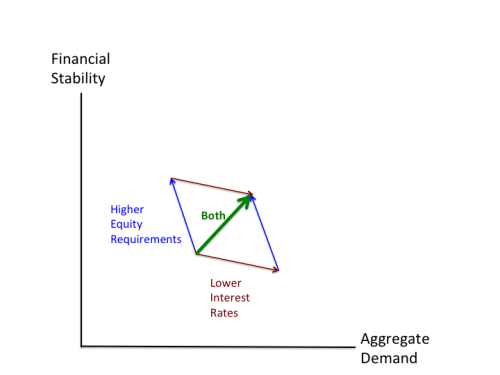

understates the power of high capital requirements and low leverage limits to stabilize the financial markets once negative interest rate policy frees one from worrying about insufficient aggregate demand. Let me reproduce here my diagram from “Why Financial Stability Concerns Are Not a Reason to Shy Away from a Robust Negative Interest Rate Policy,” which is explained more there:

5. Finally, Judy is one-third right in saying

Money should function as a reliable measuring tool and dependable store of value—not as an instrument of government policy.

Money should indeed function as a reliable measuring tool. Negative rate policy makes it possible to do short-run stabilization while maintaining a zero inflation target that preserves money as a reliable measuring tool.

On the other hand, dependable stores of value should be more closely linked with the real side of the economy than money is. The zero lower bound problem that made the Great Recession and its sad aftermath drag on for so long comes from making money too good a store of value relative to the real investments in the economy that we need people to be making.

Finally, I think money is needed as an instrument of short-run economic policy. The alternative of short-run variation in government spending and taxing to stabilize the economy is much, much more troublesome. Short-run fiscal policy distracts greatly from long-run fiscal issues. Also, because short-run fiscal policy takes legislative time, it distracts from supply-side reform in a way that monetary policy does not.

It is one thing to say that government policy about money ought to be something simple like stabilizing the growth rate of nominal GDP as Milton Friedman recommended. It is quite another to say that money shouldn’t be an instrument of government policy at all. The only “neutral” monetary policy I know of is a monetary policy that is actually quite sophisticated: something like “conduct monetary policy so that the economy stays at the natural level of output” or “stabilize the growth rate of nominal GDP.” The idea that a neutral monetary policy that will get good results can be something simpler than that is a will-o’-the-wisp that will forever elude the grasp of those searching for it.

Conclusion: No one should be allowed to get away with the kind of claims that Judy Shelton makes in her op-ed without directly answering the kinds of objections I just made to those claims. The sheer repetition of claims like the ones Judy makes does not make them true. They need to be defended.

More on Original Sin and the Aggregate Demand Effects of Interest Rate Cuts: Olivier Wang and Miles Kimball

Link to Wikimedia Commons page for “Girl with a Pomegranate” by William Bouguereau. The pomegranate connects to the classical Greek myth of Persephone as well as not being excluded by the Bible as a possibility for the forbidden fruit whose consumption constituted original sin.

In response to my post “How the Original Sin of Borrowing in a Foreign Currency Can Reduce the Effectiveness of Monetary Policy for Both the Borrowing and Lending Country” I received an interesting email from MIT graduate student Olivier Wang that led to the exchange below. (You will need to read “How the Original Sin of Borrowing in a Foreign Currency Can Reduce the Effectiveness of Monetary Policy for Both the Borrowing and Lending Country” first in order to understand this exchange. I am grateful to Olivier for permission to share this with you:

Olivier: I am a graduate student at MIT and I’ve been enjoying your blog a lot, so thank you! I’ve worked on some of the issues in your post on foreign currency borrowing. Whether a “depreciation makes debts look larger” depends on the pass-through of exchange rate to import prices. In the extreme but most studied case where prices are sticky in the foreign exporters’ currency and the depreciation is fully passed through (an assumption known as PCP), the real external debt burden stays invariant and original sin does not prevent monetary policy from stimulating the economy.

Another popular way to model contractionary depreciations has been to add a financial accelerator. If firms’ investments is constrained by their net worth, the depreciation will hurt the net worth of the currency mismatched firms and this effect might dominate the boost to net worth induced by the expenditure switching of consumers towards domestic goods.

Miles: Thanks for letting me know about this. I confess I don’t understand this:

One detail I emphasize there is that whether a “depreciation makes debts look larger” depends on the pass-through of exchange rate to import prices. In the extreme but most studied case where prices are sticky in the foreign exporters’ currency and the depreciation is fully passed through (an assumption known as PCP), the real external debt burden stays invariant and original sin does not prevent monetary policy from stimulating the economy.

If the thing I (the debtor-in-foreign-currency country) am exporting has a world price, then I effectively have another asset that goes up in value relative to my own currency when my currency depreciates. But if it isn’t that, I don’t understand the paragraph above at all. Could you help me out by trying to explain this to me a little more?I do understand the financial accelerator better. I should mention that sometimes wealth is not just wealth but also collateral.

Olivier: Apologies for being too cryptic. Suppose that as a consequence of an interest rate decrease, the Chilean exchange rate depreciates from 1 to 1.1 pesos per dollar. If I am a Chilean firm or household owing $100 abroad, my debt will indeed jump to 110 pesos, making me cut back on investment or consumption. But if the price of the foreign goods that I import (such imports being why I have this dollar debt in the first place) are set in dollars and don’t move much in the short run, their peso price also jumps by 10%, which makes me substitute towards domestic varieties of the same goods or simply buy different domestic goods (whose peso prices are also fixed in the short-run).

As everybody in the country does so, my own peso income also increases, and under these extreme pricing assumptions, the general equilibrium feedback and the reevaluation of the foreign currency debt net out, and the interest rate cut remains expansionary. Still, the economy is less stimulated than if the debt were denominated in pesos, as in this case an unexpected depreciation would directly transfer wealth from foreign creditors to domestic debtors.

If however the sticky price of half of my imported goods is set in pesos, the depreciation will only raise the price of the basket of imports by 5%, and the debt reevaluation will dominate. Taking this into account, the Chilean central bank might decide not to cut rates so much in response to domestic shocks.

All this is on top of the increased peso revenue from my exports that you mention, and which would be the most relevant effect in the case of Chile.

Miles: Thanks, Olivier! So a substitution effect toward domestic goods raises aggregate demand. I missed that.

John Locke on Legitimate Political Power

John Locke, in the 2d and 3d paragraphs of the “Introduction” to his 2d Treatise on Government: “On Civil Government” makes the radical claim that political power is only justified when it is for the benefit of the governed. He begins by denying that traditional or military hierarchical superiority is a good model for political power, than goes on to rest political power on the foundation of benefitting the governed:

To this purpose, I think it may not be amiss, to set down what I take to be political power; that the power of a magistrate over a subject may be distinguished from that of a father over his children, a master over his servant, a husband over his wife, and a lord over his slave. All which distinct powers happening sometimes together in the same man, if he be considered under these different relations, it may help us to distinguish these powers one from another, and shew the difference betwixt a ruler of a commonwealth, a father of a family, and a captain of a galley.

Political power, then, I take to be a right of making laws with penalties of death, and consequently all less penalties, for the regulating and preserving of property, and of employing the force of the community, in the execution of such laws, and in the defence of the commonwealth from foreign injury; and all this only for the public good.

What does the principle that political power must be “for the public good” to be legitimate mean for the legitimacy of democracy? First, it may be possible for a nondemocratic form of government to be legitimate if somehow it had strong institutional constraints that made it operate only for the good of the people. For example, if truly random-sample surveys were the foundation of authority rather than elections, and the survey organization were as incorruptible as the very best election authorities, the political power based on that survey data could be legitimate.

Second, democracy does not automatically yield legitimate political authority. Except in very rare cases, “the consent of the governed” is a myth because–almost always–a substantial minority voted against whatever candidate or policy was up for vote. The welfare of those who voted against a policy–or worse, were not allowed to vote at all, perhaps because of being underage or called “non-citizens”–needs to be taken into account, too, for the political power to be legitimate.

Let me try to be specific about a rule for limiting legitimate political power. It seems hard to me to justify the use of net-freedom-reducing government coercion for ends that lower net Utilitarian social welfare. Government action should either be freedom-enhancing, or raise Utilitarian social welfare, otherwise that action is illegitimate. The contrasting idea that will of the majority constitutes “consent of the governed” and can justify whatever the majority wants within a wide, wide range of actions seems quite questionable.

Of course, where there are disputes about whether something is freedom-enhancing and whether it raises Utilitarian social welfare, there has to be some decision-making mechanism, and democratic choices deserve some deference. But, for example, where it is clear to everyone who looks closely, that by a coercive action of government, members of the middle class are being benefitted a little each by hurting the poor a lot, I don’t see the legitimacy.

Don't miss other John Locke posts. Links at "John Locke's State of Nature and State of War."

Timeline: The True History of the World and Its Temperature in Cartoons →

This is a lot of fun. Hat tip to Joseph Kimball

Henry George on the Value of Transparent Theory

“When I was a boy I went down to the wharf with another boy to see the first iron steamship that had ever crossed the ocean to Philadelphia. Now, hearing of an iron steamship seemed to us then a good deal like hearing of a leaden kite or a wooden cooking-stove. But we had not been long aboard of her, before my comrade said in a tone of contemptuous disgust: “Pooh! I see how it is. She’s all lined with wood; that’s the reason she floats.” I could not controvert him for the moment, but I was not satisfied, and sitting down on the wharf when he left me, I set to work trying mental experiments. If it was the wood inside of her that made her float, then the more wood the higher she would float; and, mentally, I loaded her up with wood. But, as I was familiar with the process of making boats out of blocks of wood, I at once saw that, instead of floating higher, she would sink deeper. Then, I mentally took all the wood out of her, as we dug out our wooden boats, and saw that thus lightened she would float higher still. Then, in imagination, I jammed a hole in her, and saw that the water would run in and she would sink, as did our wooden boats when ballasted with leaden keels. And, thus I saw, as clearly as though I could have actually made these experiments with the steamer, that it was not the wooden lining that made her float, but her hollowness, or, as I would now phrase it, her displacement of water. In such ways as this, with which we are all familiar, we can isolate, analyse or combine economic principles, and, by extending or diminishing the scale of propositions, either subject them to inspection through a mental magnifying glass or bring a larger field into view. And this each one can do for himself. In the inquiry upon which we are about to enter, all I ask of the reader is that he shall in nothing trust to me.”

Ana Swanson Interviews Ken Rogoff about “The Curse of Cash”

I highly recommend Ken Rogoff’s new book, The Curse of Cash. It has several chapters that touch on my proposal to engineer a nonzero rate of return on paper currency by taking paper currency off par. The other main part of the book is about the crime-control benefits of eliminating high-denomination bills–and perhaps having physically large, but low-value coins as the only form of hand-to-hand currency.

I was an official reviewer of the book, and in that capacity strongly urged the publisher to get the book in print as soon as possible. Here is my blurb that is included in the book:

The Curse of Cash is brilliant and insightful. In addition to giving a vivid picture of the cash-crime nexus, The Curse of Cash is the book everyone should read about negative interest rates. –Miles Kimball

Ana Swanson of Wonkblog interviewed Ken Rogoff about The Curse of Cash. Here are some interesting quotations from Ken Rogoff in that interview that focus on monetary policy:

1. … the fact that monetary policy has been paralyzed because of the zero lower bound has hurt, and it will hurt in the next recession. The European Central Bank, the Nordic central banks, the Bank of Japan, they have tiptoed into negative rate territory, but they haven’t been able to do much, because they’re worried about the run into cash.

If you look at what’s happened in Europe and Japan, Japan has done quantitative easing on a scale that’s already triple what the U.S. has done. Europe is on track to buy up 20 percent of all corporate bonds within the time frame of their new quantitative-easing policy, and it’s not working very effectively. I think negative interest rates would be vastly more effective. Central bankers can’t come out and say that, but I think they all wish they had that tool. Not so they could use it today, but if something really bad happens.

2. There are other ways to do it. You can basically tax currency, by charging people when they turn currency in at the bank, which is an idea that I trace back to Kublai Khan.

3. … if you can go to a negative interest-rate policy, it’s going to depreciate the exchange rate. That said, if you wait a year or two after the policy, the negative interest rate will be gone, the U.S. economy will have strengthened, and the dollar might be higher than where it started. It’s certainly going to be controversial, but it might not be as bad as what we have now. Now no one really knows what central banks are going to do, because they’re flailing away at the zero bound trying to find something that works, and it creates an enormous amount of uncertainty.

So negative interest rates are going to come. Central bankers need them in the current environment. In 10 to 15 years, certainly in 20 years, if it’s needed, they’ll have figured out how to do it. And when they finally find a way, I think it will be regarded as leading to a better and healthier financial system.

The second quotation is referring elliptically to my proposal, which Ken discusses in detail, quite approvingly, in the book.

Henry George Eloquently Makes the Case that Correlation Is Not Causation

“That a thing exists with or follows another thing is no proof that it is because of that other thing. This assumption is the fallacy post hoc, ergo propter hoc, which leads, if admitted, to the most preposterous conclusions. Wages in the United States are higher than in England, and we differ from England in having a protective tariff. But the assumption that the one fact is because of the other, is no more valid than would be the assumption that these higher wages are due to our decimal coinage or to our republican form of government. That England has grown in wealth since the abolition of protection proves no more for free trade than the growth of the United States under a protective tariff does for protection. It does not follow that an institution is good because a country has prospered under it, nor bad because a country in which it exists in not prosperous. It does not even follow that institutions to be found in all prosperous countries and not to be found in backward countries are therefore beneficial. For this, at various times, might have been confidently asserted of slavery, of polygamy, of aristocracy, of established churches, and it may still be asserted of public debts, of private property in land, of pauperism, or of the existence of distinctively vicious or criminal classes. Nor even when it can be shown that certain changes in the prosperity of a country, of an industry, or of a class, have followed certain other changes in laws or institutions can it be inferred that the two are related to each other as effect and cause, unless it can also be shown that the assigned cause tends to produce the assigned effect, or unless, what is clearly impossible in most cases, it can be shown that there is no other cause to which the effect can be attributed. The almost endless multiplicity of causes constantly operating in human societies, and the almost endless interference of effect with effect, make that popular mode of reasoning which logicians call the method of simple enumeration worse than useless in social investigations.”

Randy Barnett's Bad List of Supreme Court Decisions

“Growing up, I was like most Americans in my reverence for the Constitution. … Until I took Constitutional Law at Harvard Law School. The experience was completely disillusioning, but not because of the professor, Laurence Tribe, who was an engaging and open-minded teacher. No, what disillusioned me was reading the opinions of the U.S. Supreme Court. Throughout the semester, as we covered one constitutional clause after another, passages that sounded great to me were drained by the Court of their obviously power-constraining meanings. First was the Necessary and Proper Clause in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), then the Commerce Clause (a bit) in Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), then the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment in The Slaughter-House Cases (1873), then the Commerce Clause (this time in earnest) in Wickard v. Filburn (1942), and the Ninth Amendment in United Public Workers v. Mitchell (1947).”

Randy Barnett, in Restoring the Lost Constitution: The Presumption of Liberty

Addendum: Brad Delong replied to this quotation post with “No, State Governments Have Not Been the Sacred Hearths of Human Liberty in America. Why Do You Ask?” making the excellent point that states rights in the US have historically been used for ignoble ends and should not be accorded the same respect as individual rights. Asserting the supremacy of the federal government over state governments can easily enhance, rather than diminish, individual rights. The reason I posted this quotation is because I lament the decisions gutting the “Privileges and Immunities Clause” and the Ninth Amendment–both of which are about individual rights, not states’ rights.

How the Original Sin of Borrowing in a Foreign Currency Can Reduce the Effectiveness of Monetary Policy for Both the Borrowing and Lending Country

Link to Wikipedia article for “Original sin (economics)”

When a central bank cuts interest rates, each type of borrower-lender relationship generates more aggregate demand because (a) the shift in of the budget constraint of the lender is matched by an equal and opposite shift out in the budget constraints of the borrower, (b) borrowers generally have higher marginal propensities to consume out of changes in effective wealth and © beyond the sum of wealth effects from (a) and (b), there is also a substitution effect leading to more spending now simply because lower interest rates make spending now cheaper relative to spending later than it was before the interest rate cut. (a) is the “principle of countervailing wealth effects” I discuss in these three posts:

- Even Central Bankers Need Lessons on the Transmission Mechanism for Negative Interest Rates

- Responding to Joseph Stiglitz on Negative Interest Rates.

- Negative Rates and the Fiscal Theory of the Price Level

The Open Economy

I laid out the principle of countervailing wealth effects in “Even Central Bankers Need Lessons on the Transmission Mechanism for Negative Interest Rates” in order to dispute the idea that causing one’s currency to depreciate was almost the sole transmission mechanism for interest rate cuts into the negative range, so I concentrated on the case where every central bank in the world simultaneously cut its target rate by 100 basis points. But it is interesting considering the open economy case with only one central bank cutting its target rate.

First, it is important to realize that thinking about wealth and substitution effects in the way I describe above is only telling about consumption and investment. The extra net exports from the outward capital flow as funds flee the low domestic interests by going abroad is an addition to aggregate demand that goes beyond the wealth and substitution effect logic above.

See “International Finance: A Primer” for why funds going outward drive net exports up. That post also explains how the outward capital flow puts more of the domestic currency in the hands of foreigners and thereby drives down the foreign-exchange value of the domestic currency.

Small Open Economy, Net Creditor in Foreign-Denominated Assets. To see if there is any chance that the wealth and substitution effect logic can overturn the effect of increased capital outflow on aggregate demand, let’s begin by considering a small open economy that is a net creditor. To the extent that anyone in the country is investing domestically both before an interest rate cut, the usual principle of countervailing wealth effects holds since both borrower and lender are domestic. Because it is a small open economy, the rate of return on foreign assets should be affected by this monetary policy move only to the extent it induces expected exchange rate movements. If people expect any mean reversion of the exchange rate, the usual depreciation of the local currency accompanying a domestic interest rate cut might make people expect a bit of mean reversion and therefore a bit lower returns on foreign assets than before the interest rate cut. But overwhelming this effect, depreciation of the domestic currency makes any foreign assets already owned look bigger in value when totaled up in the depreciate domestic currency. Overall, there is very little room for any ambiguity about the stimulative effect of interest rates cuts for a small open economy that is a net creditor: there is the stimulus to net exports from increased capital outflow, plus a higher return on foreign assets when viewed in the domestic currency, plus the higher value of foreign assets when viewed from the perspective of the domestic currency.

Large Open Economy, Net Creditor in Foreign Denominated Assets. Now, consider a large open economy that is a net creditor. As with any monopolist that drives down prices by producing more and selling it, a net creditor country that increases its lending abroad could theoretically reduce the rates of return it gets abroad and so make itself effectively poorer. If this were the case, one would expect to have at least some people in that country suggest that it have policies to reduce its foreign lending in order to jack up its returns on foreign assets. In the absence of any such suggestion, it seems unlikely that a country in fact would make itself significantly poorer by increasing its foreign lending from its current level.

Net Creditor in Own Currency. If a country does significant lending in its own currency, such lending is still driven by interest rates abroad relative to interest rates at home, and like the purchase of foreign-denominated assets, puts the domestic currency in the hands of foreigners, who are likely to turn around and spend those funds in increasing net exports from the domestic economy. However, with the lending in the domestic currency, exchange rate changes no longer change wealth as viewed in the domestic currency. It now becomes logically possible for a cut in interest rates to reduce spending simply because of the reduced interest income from foreigners when rates are cut.

Germany. There are three ways of thinking of the situation for Germany. One is that seeing Germany as a set of creditors within the eurozone, where the entire eurozone is seen as domestic. When taking the eurozone as the main unit of analysis, and Germany as only a part, German lending to others in the eurozone is all internal and the principle of countervailing wealth effects still applies in its main form to the eurozone as a whole.

Second, Germany can be seen as a net creditor in its own currency.

Third, one can view the situation as the other countries in the eurozone automatically loosening their monetary policy when Germany does. The other countries loosening their monetary policy cancels out the exchange rate effects that would otherwise make the foreign assets Germans hold in other eurozone countries look like more wealth when Germany loosens its monetary policy.

Net Debtor in Own Currency. If a country owes money on net, primarily in its own currency, then in this borrower-lender relationship, a cut in interest rates will have a positive wealth on consumption by this debtor country, enhancing the positive effects on aggregate demand from borrower-lender relationships within the country, and from the capital outflow and consequent increase in net exports induced by a rate cut.

Small Open Economy, Net Debtor in Foreign-Denominated Obligations. This case is sometimes called “original sin.” Depreciation now makes debts look larger, which should overwhelm the effect of expected mean reversion in the exchange rate in lower the rate of return on those debts. If foreign-denominated obligations are large enough, it might even become impossible to stimulate the economy with an interest rate cut. Thus, getting into this situation is quite dangerous. Countries should put policies into place to avoid owing large amounts of money in foreign-denominated obligations. And the IMF should proactively discourage countries from committing the original sin of borrowing with foreign-denominated obligations.

Large Open Economy, Net Debtor in Foreign-Denominated Obligations. This does not literally mean a large economy, but only one that must pay higher interest rates when it owes more and can pay lower rates when it owes less. Assuming a depreciation of the currency from a monetary loosening that reduces the rate on own-currency debt raises net exports enough that a bit of the debt begins to be paid off and the rate paid on all of the foreign-denominated debt goes down when it is rolled over, that provides a bit of an extra wealth effect in the positive direction.

Summary

Overall, the main potential loopholes to the argument that interest rate cuts should stimulate the economy come from a country’s being a large net creditor in its own currency, or a country’s being a large net debtor in foreign-denominated obligations. In both cases, someone is borrowing in a foreign currency. Overall, having countries borrow primarily in their own currency if they do borrow is an important measure for maintaining the effectiveness of monetary policy.

Note: I am worried about the chance that I might have missed some important element of the analysis I pursue in this post. Send me a tweet (@mileskimball) if you think I got something wrong or missed something.

Update: Olivier Wang’s reply to this post generated the follow-up post “More on Original Sin and the Aggregate Demand Effects of Interest Rate Cuts: Olivier Wang and Miles Kimball.”