The Swiss National Bank and Bank of Japan’s New Tool to Block Massive Paper Currency Storage

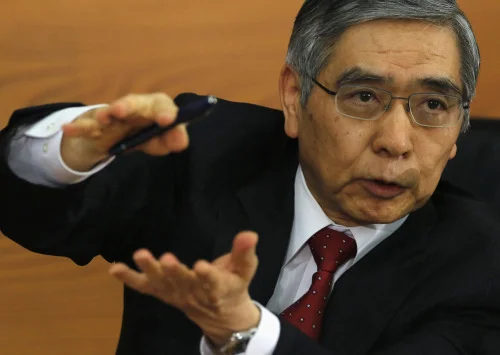

The Bank of Japan’s New Negative Interest Rate Policy

The Bank of Japan surprised the world by going to negative interest rates on January 29, 2016. You can read more about that move in Reporting on Japan’s Move to Negative Interest Rates and in these 3 news articles (1, 2, 3). But there are important aspects of the Bank of Japan’s new policy that are only now being appreciated.

I have written a great deal about negative interest rate policy. (I have organized relevant links here.) But, thanks to Noah Smith pointing me to Martin Sandbu’s February 4, 2016 article in the Economics “Free Lunch: There is no lower bound on interest rates,” I realize that the Swiss National Bank–with the Bank of Japan following in its footsteps–has hit upon an additional tool for blocking massive paper currency storage that I hadn’t thought of. Here is how Martin Sandbu describes it:

But the Bank of Japan’s set-up for negative rates, which apparently follows the Swiss National Bank’s, casts doubt on the premise that the nominal cost of holding cash is zero. As we have explained, if a private Japanese bank wishes to exchange its central bank reserves for cash, the BoJ will adjust the portion of its reserves to which negative rates apply by the same amount. That means any extra cash that a bank wishes to hold will cost it as much as if it kept it on deposit at the central bank.

And here is the description from the Bank of Japan’s official statement about its new negative interest rate policy:

2. Adjustment concerning a significant increase in financial institutions’ cash holdings

In order to prevent a decrease in the effects of a negative interest rate due to financial institutions’ cash holdings, if their cash holdings increase significantly from those during the benchmark reserve maintenance periods, the increased amount will be deducted from the macro add-on balance in (2). In cases where the increased amount is larger than the macro add-on balance, the amount in excess of the macro add-on balance will be further deducted from the basic balance in (1).

A Negative Paper Currency Interest Rate on Cumulative Net Withdrawals from the Cash Window

What is fascinating is this: a central bank can effectively impose a negative interest rate on additions to cash holdings by saying that any bank with access to the cash window is on the hook for whatever paper currency interest rate the central bank decides to charge on cumulative net withdrawals of paper currency by that bank after a certain date regardless of who actually ends up with that paper currency. Then it is up to the bank to figure out how and whether to pass on to its customers the negative paper currency interest rate it faces on that extra paper currency. Martin Sandbu’s article has a nice discussion of how pass-through might work.

One chink in the armor of this mechanism for imposing negative interest rates on cumulative net withdrawals of paper currency would be if a bank went bankrupt after withdrawing a huge amount of cash at the cash window and handing off that cash to favored individuals. But that doesn’t seem like a big issue. Surely the number of banks that have access to the cash window willing to intentionally go bankrupt to help favored individuals get paper currency not subject to the negative interest rate is limited, and there may be some way for the government to prosecute the individuals who organized this scheme of using bankruptcy to circumvent the negative interest rate on additional paper currency.

No Limit to How Low the Marginal Paper Currency Interest Rate Through the Negative Rate on Cumulative Net Cash Withdrawals Mechanism Can Go

One thing that the Bank of Japan may not yet have realized is that banks can be charged for net cash withdrawals even beyond an amount equal to the bank’s initial reserves. As it is now, the policy is represented as a policy about how much of reserves is exempted from the negative interest rates, or even receives a +.1% interest rate, but that need not be the case. Banks can be charged interest on cumulative net cash withdrawals quite apart from how their reserve accounts are handled. For now, the Bank of Japan has made a good choice to charge the negative paper currency interest rate through the formula for interest on reserves, but it should not stop there if very large amounts of paper currency are withdrawn.

The Central Bank Can Limit Cash Withdrawals by Limiting the Total Size of the Monetary Base

Speaking of the possibility of cash withdrawals exceed initial reserves, another additional tool that I will mention only briefly is that if negative interest rates are adequate to get velocity up on a given monetary base, limits on the monetary base may limit the total amount of paper currency that can be withdrawn. This is a point I take from Martin Sandbu, who wrote in “Free Lunch: There is no lower bound on interest rates”:

And how could private banks honour mass withdrawals of cash even if they wanted to? No law provides for the central bank to swap client deposits for cash; only central bank reserves. And despite the huge growth of reserves in recent years, these still amount to only a fraction (about one-fifth in the UK) of bank deposits.

What If the Paper Currency Interest Rate is Lowered in the Future?

It might seem unfair for a central bank to lower the interest rate on cumulative net cash withdrawals that are already out there. There is a flavor of retroactivity to it. But if a bank only gets a -.2% rate on net withdrawals after a certain date and -.1% before, then it might try to withdraw a lot of paper currency right before it predicted the paper currency interest rate on further net withdrawals after would be cut. If it knows the rate can be cut on what is already out there, there is no such incentive to pull out cash under the wire.

An alternative to making rate cuts on net paper currency withdrawals retroactive to the inception of the negative interest rate policy would be to have a schedule saying that, for example, a bank gets -.1% on the first 5% of its previous year’s reserve balance in cash, -.2% on the next 5%, -.3% on the next 5% after that, etc.

A Warning: Side Effects of a Negative Paper Currency Interest Rate on Cumulative Net Withdrawals from the Cash Window

Although the central bank can easily do so to the private bank, it is probably not as easy for that private bank to keep charging a retail customer a negative interest rate month after month on cumulative net cash withdrawals. In principle, a bank could keep charging such a “rental fee” on net cash out to a customer, but what is to stop a customer from withdrawing a lot of cash, and then cutting all ties to the bank? (This is analogous to the intentional bankruptcy discussed above, but much easier.) Even if a contract still obligated the former customer to keep paying the rental fee on the net cash out, it is a lot of trouble for the bank to track that customer down and collect the fee–especially for modest amounts.

As a result, private banks are likely to charge a substantial one-time fee on withdrawal of cash to make it worth their while to give out cash, or impose severe restrictions on cash withdrawals. This will interfere with the normal use of paper currency. This may not happen immediately, but is likely to emerge over time (and of course depends on exactly what interest rate the Bank of Japan is imposing, and how long banks expect negative interest rates to last).

What is worse, restrictions or fees on withdrawals by themselves will tend to push the value of paper yen in circulation–on which fees have already been paid–above the value of electronic yen. If banks charge a fee for giving out paper currency, so can retailers. In Japan, many, many retailers only accept paper currency even now. If paper currency is going at a premium, more and more retailers are likely to declare that they only accept paper currency. This further paperization of the Japanese economy will make negative electronic interest rates less effective. (The negative paper currency interest rates don’t do the trick because they are not passed through; therefore, the burden falls on the negative electronic interest rates and on transactions made in electronic form.)

In addition to these serious problems from a paper currency policy that pushes paper currency above par, the exact exchange rate between paper currency and electronic money could be quite volatile. That is, the effective exchange rate between paper currency and electronic money that follows a jagged path over time like a stock price plot as people get new information about the future.

By contrast, in my main proposal of a time-varying paper currency deposit fee at the cash window, if a private bank passes the time-varying paper currency deposit fee to retail customers (including extra cash upon withdrawal), the effective exchange rate between paper currency and electronic money at the bank will follow a very smooth, sedate path. I recommend that smooth, sedate path–with a below-par rather than above-par value for paper currency.

How the Bank of Japan’s Policy Uses Two Key Innovations I Have Made in Negative Interest Rate Paper Currency Policy

In addition to giving a well-attended presentation on “Breaking Through the Zero Lower Bound” at the Bank of Japan on June 18, 2013 (and on June 24, 2013 at Japan’s Ministry of Finance), I spent 2 weeks each in the summers of 2008 and 2009 as a visiting research fellow at the Bank of Japan, and have several former students on staff there. I also made a point of arranging a seminar at the Bank of Japan on June 8, 2010 (on an unrelated paper) in order to have a chance to remind the staff at the Bank of Japan about the potential of negative interest rate policy. So I am confident that some staffers within the Bank of Japan have read my work carefully (including my work with Ruchir Agarwal on the IMF Working Paper “Breaking Through the Zero Lower Bound,” which is prominently featured here).

I have no idea whether those who actually designed the Bank of Japan’s new policy have read my work or not. Nevertheless the Bank of Japan’s new policy has the two key features that are my innovations over the negative interest rate paper currency policy tools laid out by Willem Buiter:

- Existing paper currency is used.

- The policy is focused on the central bank’s interaction with private banks. The private banks are left to decide pass-through on their own.

The advantage of using existing paper currency is obvious. The advantage of letting private banks handle pass through is that the private banks, for their own benefit, will be inventive at trying to minimize the annoyance to customers from the negative interest rate policy as much as possible given what the central bank has done. In addition, having the central bank focus only on its interaction with private banks makes the central bank’s job more manageable. It doesn’t need to think through quite as many things, since the private banks have, in effect, been deputized to work out the details of what happens at the retail level. (One limitation to this principle is that there has to exist some way for the private banks to pass the policy through–or not–that goes some distance toward achieving the macroeconomic goals without serious side effects.)

How the Bank of Japan’s Paper Currency Policy is Different from the One I Recommend

In my presentations to central banks around the world, I warn of the problems that arise from trying to restrict or penalize withdrawal of paper currency. We may soon learn more about these problems from experience. And of course the details of the policy matter. In the case of the Bank of Japan’s policy, the emergence of an above-par, jagged price of paper currency and further paperization of the economy by more and more retailers only accepting paper currency are the most worrisome problems.

Note that–as discussed above–these problems have to do with the particular difficulties private banks will have in passing through the negative paper currency interest rates in the form that the Bank of Japan is imposing them on the banks. If the banks could pass the negative paper currency interest rates on in a similar form, there would be no great problem.

The best course would be to follow my recommendation of a gradually changing below-par value for paper currency at the cash window of the central bank. If restrictions, penalties or fees on withdrawals–or what will result in private banks imposing restrictions, penalties or fees on withdrawals–must be used, they should be used in combination with other policies, including policies that tend to push the price of paper currency down. The possibility of second- or third-best negative interest rate paper currency policies that try to keep the relative price of paper currency close to par is the subject of an upcoming post.

Why the Bank of Japan’s Move is So Remarkable

I thought it would be at least another year–into 2017–before the Bank of Japan went to negative interest rates–partly because to do so would be a tacit admission that its previous QE-only policy was not working as hoped. It was a genuine act of courage for the Bank of Japan’s monetary policy committee to admit that it needed something more. I applaud them.

But what is even more remarkable is that they were willing to begin to modify paper currency policy. And make no mistake, as a practical matter, it is paper currency policy traditions that create the zero lower bound. So the Bank of Japan has made a small step down the road toward abolishing the zero lower bound–a small step that could ultimately be part of a giant leap for humankind.

Update 1: A reader points out that the Bank of Japan’s statement of its policy above can easily be interpreted as applying only to a bank’s own holdings of paper currency, which would not include paper currency it passed on to customers. (Many people have, in fact, interpreted it that way.) In that case, this would be a charge for storage of paper currency rather than a charge for cumulative net withdrawals of paper currency by banks. If that is the right interpretation, I am glad I misunderstood the statement so I could see the interesting possibility of a charge on cumulative net withdrawals. But I am also glad to be corrected about what the actual current policy is.

In the event, if a bank made large paper currency withdrawals to pass paper currency on to customers, I suspect the Bank of Japan would try to do something to discourage that flow. Since the Bank of Japan is making the policy itself (and there is a tradition in Japan of administrative discretion) a private bank should worry about what the Bank of Japan would do if the private bank became a conduit for a large amount of paper currency to customers.

Update 2: The Swiss National Bank’s corresponding statement for its policy (on which the Bank of Japan’s policy is probably modeled) is clearer:

Minimum reserve requirement of the reporting period 20 October 2014 to 19 November 2014 times 20 (static component). –/+ Increase/decrease in cash holdings resulting from comparison of cash holdings in current reporting period and corresponding reporting period in given reference period (dynamic component) = Exemption threshold

Thanks to JP Koning for this point.

Update 3: Makoto Shimizu gives an answer to Update 1. This is so important, it has its own post. Don’t miss “Makoto Shimizu Reports on the Bank of Japan’s New Tool to Block Massive Paper Currency Storage.”