Is It a Problem for Negative Interest Rate Policy If People Hang On to Their Paper Currency?

I teach how to break through the zero lower bound in my “Monetary and Financial Theory” class. I got an interesting question from one of my students, Matthew Hoffman (who chose fame over anonymity when I told him I wanted to write this Q&A post. Here are his questions and my answers.

Matthew: I understand that electronic money would be the unit of account, and that the deposit fee, in a time of negative interest rates, would eliminate the ZLB as the paper currency is charged roughly the value of the negative rate upon deposit. So my question is what stops people from just taking all of their money out and holding it as cash? You give three ways to act against paper currency storage, but since you advocate the third method (the fee on deposits) why can’t people still withdraw all of their money in cash and then not re-deposit until the deposit fee is “allowed to shrink when the interest rate is positive?”

Is the answer to my question explained in part “B. The Paper Currency Interest Rate,” in that since the electronic money is the unit of account, then the deposit fee still affects the value of paper currency regardless of whether it’s in the bank or under the mattress? For example, if I take a $100 bill out of the bank when the deposit fee is 2%, then is the value of my bill only $98 if I go to the mall? Or is it still worth $100, but when I go to re-deposit it, at that point it will be worth only $98 and I essentially lost $2 by putting it in the bank?

Miles: Excellent questions!

- Note that over the horizon where paper currency earns a zero interest rate, money in the bank also does. So that creates no incentive to take out paper currency–though it also provides no disincentive.

- At retail, paper currency will be at par for a while. If I take out cash and spend it, that stimulates the economy. So that is OK. It doesn’t stop the policy from working.

- The interest rate for small checking and saving accounts may stay zero if interest rates are not too low, and to somewhat lower interest rates if the central bank subsidizes zero interest rates in small checking and saving accounts. If so, then those folks wouldn’t have any temptation to withdraw paper currency in any case.

Notice that in no case is there an arbitrage that stops interest rates from being deeply negative.

Matthew: One follow up question…so would cash that was already under the mattress when the Fed increases the deposit fee still be worth its face value? It would only be worth less if it were deposited? This is like your second point in your previous email I believe…the value will stay at par for awhile and that cash can stimulate the economy if spent.

Miles: If used for purchases reasonably promptly, paper currency households already had could probably be spent at par. And most business try to deposit their paper currency in the bank quickly, while the exchange rate changes very slowly. So paper currency on hand at the beginning of the electronic money system should not be a big deal for them.

Brian Blackstone: Deflation Holds No Terrors for Those Who Know How to Use Negative Interest Rates

I have criticized Wall Street Journal reporter Brian Blackstone in the past for not appreciating the power of negative interest rate policy:

- The Wall Street Journal’s Big Page One Monetary Policy Mistake

- Brian Blackstone Doubles Down on a Big Mistake in Reporting on Monetary Policy

But Brian Blackstone is beginning to show a greater appreciation for negative interest rates in his October 18, 2015 Wall Street Journal article

- “Switzerland Offers Counterpoint on Deflation’s Ills: Country shows falling consumer prices can go hand in hand with steady growth, low unemployment.”

Here are some of the key passages:

1. Consumer prices in Switzerland have fallen on an annual basis for most of the past four years. … Even after food and energy prices are stripped out, core prices fell 0.7%.

“It’s hard not to call that deflation,” said Jennifer McKeown of Capital Economics …

And yet evidence of deflation’s pernicious side effects—recession, weak employment, rising debt burdens—is pretty much nonexistent in Switzerland. Its economy is expected to expand this year and next, albeit slowly, in the 1% to 1.5% range. Unemployment was just 3.4% in September. Government debt is low.

2. Some of that success is due to the shattering of another long-held maxim: that central-bank policy rates can’t go negative to offset the effects of falling prices.

3. Major central banks prefer annual inflation of about 2% to provide a cushion against deflation.

4. To keep the franc in check, the central bank may be forced to cut the deposit rate even further, analysts say, particularly if the ECB eases policy more.

Brian asks the following question,

So why aren’t central banks embracing the Swiss example?

The answer he gives is this:

Analysts note that it’s difficult to distinguish between good and bad deflation until it’s too late.

But to me the answer is simpler. Deflation is not a good thing, but deflation holds no terrors if a central bank understands how to use negative interest rates. To me, this is the message of Brian’s article, though he doesn’t say it himself.

Although it hasn’t done so yet, because the Swiss National Bank knows how to make the rate of return on paper currency negative if people ever started storing large amounts of paper Swiss francs, it can dare push interest rates lower than other central banks that do not fully understand how to break through the zero lower bound.

You might be interested in the other things I have said about the Swiss National Bank and negative interest rate policy:

- The Swiss National Bank Means Business with Its Negative Rates

- Swiss Pioneers! The Swiss as the Vanguard for Negative Interest Rates

- Q&A on the Swiss National Bank’s Move to Negative Interest Rates

- Negative Interest Rates and Financial Stability: Alexander Trentin Interviews Miles Kimball

- Alexander Trentin and Sandro Rosa Interview Miles Kimball: Clinging to Paper Money is Like Clinging to Gold

- Alexander Trentin: Negative Interest Rates and the Swan Song of Cash

- 18 Misconceptions about Eliminating the Zero Lower Bound

Quartz #66—>Japan Should Be Trying Out a Next Generation Monetary Policy

Here is the full text of my 66th Quartz column, “Japan Should Be Trying Out a Next Generation Monetary Policy,” now brought home to supplysideliberal.com. It was first published on September 11, 2015. Links to all my other columns can be found here.

This column was written in conjunction with two other closely related posts that you might want check out as well:

- Is the Bank of Japan Succeeding in Its Goal of Raising Inflation?”

- An Underappreciated Power of a Central Bank: Determining the Relative Prices between the Various Forms of Money Under Its Jurisdiction

If you want to mirror the content of this post on another site, that is possible for a limited time if you read the legal notice at this link and include both a link to the original Quartz column and the following copyright notice:

© September 11, 2015: Miles Kimball, as first published on Quartz. Used by permission according to a temporary nonexclusive license expiring June 30, 2020. All rights reserved.

After twenty years of slow economic growth, Japan’s Sept. 26, 2012 election centered on Shinzo Abe’s promise to shake up monetary policy. Once in office, Abe appointed Haruhiko Kuroda to head the Bank of Japan. In short order, the Bank of Japan went from defending its monetary policy during those two lost decades of slow growth and bragging about the number of different types of assets it was buying to a serious program of quantitative easing on steroids, with a commitment to buying bonds and other securities equal in value to over half of GDP every year.

One of the announced objectives for this massive asset purchase program is to bring inflation quickly up to 2% per year. The idea is that the zero interest rate the Bank of Japan has maintained for a long time would be a more powerful stimulative for the economy if businesses and consumers were comparing it to a higher inflation rate. The logic is similar to the logic driving economists such as Olivier Blanchard, Larry Ball, and Paul Krugman to recommend raising inflation target to 4% in other countries in order to supercharge the stimulative effect of zero interest rates.

The key concept is that of a “real interest rate,” or an interest rate stated in terms of a basket of goods instead of the usual interest rate stated in terms of money.

Japan is wasting its time trying to raise inflation

Japan may succeed at bringing annual inflation up to 2%; indeed, it has made some real progress toward that goal. But suppose Japan succeeds in getting inflation up to 2%; would that be enough? The US economy has struggled mightily despite the fact that it went into the Great Recession with a 2% annual rate of core inflation. Japan could try to target an even higher rate of inflation, as Blanchard, Ball and Krugman recommend, or Japan could leave behind quantitative easing and higher inflation targets to make the leap to next-generation monetary policy.

The key to next-generation monetary policy is to cut interest rates directly instead of trying to supercharge a zero interest rate by raising inflation. Of course, cutting interest rates below zero pushes them into negative territory. But Switzerland, Denmark, Sweden and the euro zone have already shown that can be done. There is a widespread myth that cutting interest rates much deeper than -0.75% would inevitably cause people and firms to do an end run around those negative interest rates by taking their money out of the banking system as paper currency. Not so!

It is easy to neuter cash taken out of the bank as a way to defeat negative interest rates simply by removing the guarantee that the Bank of Japan will take that cash back at face value. You can find the details of how such a cash-neutralizing policy works here, here and here. This is an idea I have taken on the road that has withstood close examination and grilling by central bankers and economists all over the world. A common reaction is surprise at how easy the practical details are relative to the many much more difficult things central banks already do.

If the guarantee that the Bank of Japan (or other central bank) will always take cash back at face value is removed, it leaves no way to avoid negative interest rates without stimulating the economy. If people take cash out of the bank, store it, and then spend it, that stimulates the economy. If a firm takes a pile of money facing a negative interest rate out of the bank to build a new factory, that stimulates the economy. And even if, say, Japanese households take money that would otherwise earn a negative interest rate out of the bank to buy foreign stocks and bonds, it stimulates the Japanese economy, when excess yen in the hands of the foreigners who sold those stocks and bonds ultimately make their way back to Japan to buy Japanese products, boosting net exports.

Japan is wasting time by trying to raise inflation because it doesn’t need to raise inflation. Raising inflation is an indirect way to get the same effect that can be achieved directly by cutting interest rates. Switzerland, Denmark, Sweden and the euro zone have gingerly dipped their toes in the water of negative interest rates. Japan should go all in.

The alternatives to negative interest rates all have serious downsides. For example, increasing government spending is a bad idea: Japan already has more debt in comparison to its GDP than any other major economy—more than two years worth of GDP. (And saying that the Bank of Japan can just keep buying all that debt ad infinitum should be a last resort.) Worse, Japan has already been down the path of high government spending and has already exhausted most attractive government investment opportunities.

What about ramping up quantitative easing even more? Quantitative easing works in the right direction, but to get the needed effects requires dosages so large that no one knows what side effects it might have. By contrast, economic theory is reasonably clear about how interest rates affect the economy, even when they are negative.

Addressing Japan’s supply-side

Even if Japan makes the leap to next-generation monetary policy, it will still have serious economic problems. Many economists and politicians argue that monetary stimulus is a distraction from necessary supply-side reforms (often called “structural reforms”).

But it is a lot easier to move workers and capital from low productivity activities to higher productivity activities in a boom, than in a stagnant economy in which people worry about getting the next job or finding the next business opportunity.

Having an economy made worse by monetary policy is not a very reliable aid to jumping over political hurdles to supply-side reform. Instead, a substandard economy due to substandard monetary policy is often a temptation to more government spending and more debt. Japan should fix its monetary policy first, by eliminating any floor on interest rates. Then it can and should face its supply-side problems squarely.

Greg Robb: Fed Officials Seem Ready to Deploy Negative Interest Rates in Next Crisis

Link to the article on Market Watch

Greg Robb interviewed me on Friday evening, October 9, and by the next morning had this incisive article out. You should read the entire article, but here is the part based on our interview:

Although negative rates have a “Dr. Strangelove” feel, pushing rates into negative territory works in many ways just like a regular decline in interest rates that we’re all used to, said Miles Kimball, an economics professor at the University of Michigan and an advocate of negative rates.

But to get a big impact of negative rates, a country would have to cut rates on paper currency, he pointed out, and this would take some getting used to.

For instance, $100 in the bank would be worth only $98 after a certain period.

Because of this controversial feature, the Fed is not likely to be the first country that tries negative rates in a major way, Kimball said.

But the benefits are tantalizing, especially given the low productivity growth path facing the U.S.

With negative rates, “aggregate demand is no longer scarce,” Kimball said.

Here is a quotation I sent him over email he didn’t have space to use:

Monetary policy can’t take care of long-run growth or financial stability. But, even if we had to face again something as terrible as the Great Recession, interest rate policy alone–without any help from quantitative easing or fiscal stimulus–could provide as much aggregate demand as needed once a central bank gets cash out of the way. And it is easy to get cash out of the way by adjusting how the central bank handles paper currency. The key is to make dollars (or euro or yen) in the bank the center of the monetary system, not paper money.

For more on negative interest rates, see my bibliographic post How and Why to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound: A Reader’s Guide. There is a 5 minute video there you should watch first, then you can browse through many links.

Ben Bernanke on Trial

Previewing his upcoming book The Courage to Act: A Memoir of a Crisis and Its Aftermath slated to come out the next day, Ben Bernanke discussed recent monetary policy history and general principles of monetary policy in the October 4, 2015 Wall Street Journal op-ed “How the Fed Saved the Economy.” He said a number of important things very well. Here are my favorite passages. I added headings, but the words in the indented bits are Ben’s. After quoting Ben, I give my take on his record at the Fed.

The Limits of Monetary Policy

Fed critics sometimes argue that you can’t “print your way to prosperity,” and I agree, at least on one level. The Fed has little or no control over long-term economic fundamentals—the skills of the workforce, the energy and vision of entrepreneurs, and the pace at which new technologies are developed and adapted for commercial use.

What Monetary Policy Can Do

What the Fed can do is two things: First, by mitigating recessions, monetary policy can try to ensure that the economy makes full use of its resources, especially the workforce. High unemployment is a tragedy for the jobless, but it is also costly for taxpayers, investors and anyone interested in the health of the economy. Second, by keeping inflation low and stable, the Fed can help the market-based system function better and make it easier for people to plan for the future. Considering the economic risks posed by deflation, as well as the probability that interest rates will approach zero when inflation is very low, the Fed sets an inflation target of 2%, similar to that of most other central banks around the world.

The Record for the US, the UK and the Eurozone Indicates that the Great Recession Called for Monetary Stimulus

Europe’s failure to employ monetary and fiscal policy aggressively after the financial crisis is a big reason that eurozone output is today about 0.8% below its precrisis peak. In contrast, the output of the U.S. economy is 8.9% above the earlier peak—an enormous difference in performance. In November 2010, when the Fed undertook its second round of quantitative easing, German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble reportedly called the action “clueless.” At the time, the unemployment rates in Europe and the U.S. were 10.2% and 9.4%, respectively. Today the U.S. jobless rate is close to 5%, while the European rate has risen to 10.9%. …

Meanwhile, the United Kingdom is enjoying a solid recovery, in large part because the Bank of England pursued monetary policies similar to the Fed’s in both timing and relative magnitude.

The Supply Side

With full employment in sight, further economic growth will have to come from the supply side, primarily from increases in productivity. … As a country, we need to do more to improve worker skills, foster capital investment and support research and development.

My Take on Ben’s Record

Ben has been criticized for many things. I think that higher equity requirements–including mortgage reform involving more equity provided by not just homeowners but other investors to get higher equity requirements for mortgages–and sovereign wealth funds are the right tools to deal with financial instability, not monetary policy, so I certainly don’t follow the chorus faulting the Fed for causing bubbles by keeping interest rates too low in 2003. (Ben was not Chair then, but he was an influential Governor.)

Ben, however, like many of the rest of us (I definitely include myself) did not do enough to recognize building financial instability and push for higher equity requirements before things blew up in 2008. My now deceased University of Michigan colleague Ned Gramlich was one of the few within the Federal Reserve Board who recognized some of these building problems when he served as a Governor of the Federal Reserve Board. Like Alan Greenspan, Ben should have paid more attention to Ned, and Ned should have been more insistent on his point.

In later decisions, in hindsight, Ben should probably have pressed to save Lehman. But it is not at all clear that could have arrested the crisis, since some other bank might have then failed and pulled things down.

Nevertheless, once Lehman fell, Ben’s actions were heroic, both in helping to push through the unpopular but necessary bailouts and in bringing the Fed around to a serious program of quantitative easing that helped greatly, as Ben points out in one of the passages above.

Overall, Ben is a hero in my book. The mistakes he made are mistakes I think I would have made myself. (I know that, because I have a reasonably good memory of what I thought in real time along the way.) But what he did right was something that very few people could have done as well.

Going forward, for the future of monetary policy, my wish would be for Ben Bernanke to help in pushing for a further expansion of the monetary policy toolkit. Despite Ben’s heroic actions, the actual outcome of US monetary policy–7 years of sluggish growth and zero interest rates–was terrible in absolute terms. There is a simple reason why: the zero lower bound. As far as I know, Ben has yet to acknowledge publicly the fact that the zero lower bound is a policy choice, not a law of nature–and that ways to eliminate the zero lower bound are quite practical. See my bibliographic post “How and Why to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound: A Reader’s Guide.” In recognizing and discussing publicly how easy it is to break through the zero lower bound, Bank of England Chief Economist Andrew Haldane is ahead of Ben. As things stand, the Bank of England is poised to do a much better job in the next serious recession than the Fed. Ben could do a lot to fix that by speaking frankly about the welcome fragility of the zero lower bound.

The Economist Endorses Nominal GDP Targeting and Notes that the Zero Lower Bound is a Policy Choice, Not a Law of Nature

In a remarkable editorial, the Economist endorsed nominal GDP targeting. What is more, it is finally reporting on the zero lower bound accurately. Here are the key passages:

Endorsing NGDP Targeting as a Solution to Shifting Inflation Determination Relationships:

That is because the usual relationship between inflation and unemployment appears to have broken down. In the short run, economists think these two variables ought to move in opposite directions. High joblessness should weigh on prices; low unemployment ought to push inflation up, by raising wages.

Unfortunately, in many rich countries this standard inflation thermostat is on the blink. In 2008 economic growth collapsed and unemployment soared, but inflation only gradually sank below target. Now, by contrast, unemployment has fallen to remarkably low levels, but inflation remains anaemic. This has wrong-footed central banks.

… it makes sense to look beyond inflation—and to consider targeting nominal GDP (NGDP) instead.

… an NGDP target would free central banks from the confusion caused by the broken inflation gauge. To set policy today central banks must work out how they think inflation will respond to falling unemployment, and markets must guess at their thinking. An NGDP target would not require the distinction between forecasts for growth (and hence employment) and forecasts for inflation.

Mentioning the Zero Lower Bound in a Way that Indicates It Is a Policy Choice, Not a Law of Nature:

Interest rates cannot be cut far below zero without radical changes in the nature of money (the Bank of England’s chief economist recently suggested eliminating cash).

Tony Yates’s Worries about Breaking Through the Zero Lower Bound Are Unfounded for a System Built around Electronic Money that Keeps Paper Currency in a Subsidiary Role

I wanted to reply to Tony Yates’s post “Haldane on coping with the zero lower bound.” Tony was reacting to this passage from Bank of England Chief Economist Andrew Haldane’s recent speech, discussing the basic options for eliminating the zero lower bound that Willem Buiter detailed in the first decade of this millenium:

Over a century ago, Silvio Gesell proposed levying a stamp tax on currency to generate a negative interest rate (Gesell (1916)). Keynes discussed this scheme, approvingly, in the General Theory. More recently, a number of modern-day variants of the stamp tax on currency have been proposed – for example, by randomly invalidating banknotes by serial number (Mankiw (2009), Goodfriend (2000)).

A more radical proposal still would be to remove the ZLB constraint entirely by abolishing paper currency. This, too, has recently had its supporters (for example, Rogoff (2014)). As well as solving the ZLB problem, it has the added advantage of taxing illicit activities undertaken using paper currency, such as drug-dealing, at source.

A third option is to set an explicit exchange rate between paper currency and electronic (or bank) money. Having paper currency steadily depreciate relative to digital money effectively generates a negative interest rate on currency, provided electronic money is accepted by the public as the unit of account rather than currency. This again is an old idea (Eisler (1932)), recently revitalised and updated (for example, Kimball (2015)).

Tony responds:

Andy points out that inflation is costly, and so an extra 2 percentage points of it is proportionately more costly. Yet it seems to me that allowing negative interest rates on digital cash increases the cost of 2 per cent inflation somewhat. Formerly, consumers get zero interest on their notes and coins holdings, while they depreciate at an average of 2 per cent a year. With occasionally negative rates, these ‘shoe-leather costs’ of inflation increase a bit, proportional to the time spent below zero, and just how negative they go. A reminder: during the dark days of the previous crisis it was commonly thought that rates would ideally have gone down to about negative 7% or 8%.

Second, I query the judgement that eliminating cash and using negative rates would be less damaging to the credibility of monetary institutions than bumping up the inflation target. Ultimately, in the absence of good models of how reputations are won and lost, this argument is really about trading hunches. But mine is that there is a risk of a serious WTF moment when the no-cash system is explained, or people find out that they actually have to pay large sums of money simply for the privilege of having it. Anecdotally, we know from many models of money that equilibria where money is valued are quite fragile – specifically, it’s quite easy to write down models in which it is not.

I am not going to defend Silvio Gesell’s direct taxation of paper currency or the total abolition of paper currency. But I will defend my own recommendation, which builds on Robert Eisler’s idea of having an exchange rate between paper currency and bank money (which in modern times can be called “electronic money” since it is encoded in the memory banks of computers).

Tony has two worries. The first is a worry about “shoe-leather costs”–people being overly discouraged from using paper currency. But shoe-leather costs are all about the spread between the paper currency interest rate and other safe interest rates. My recommendation to central banks is to keep the paper currency interest within 50 basis points of the target rate at all times, except when that would push a paper dollar toward being worth more than an electronic dollar. Consider in particular the baseline case of a paper currency equal to the target rate whenever that doesn’t take paper currency above par. Then there are no shoe-leather costs when paper currency is away from par.

If a central bank follows this recommendation, paper currency is at par only during periods of time when the target rate is positive, and things are very much as under the current system when the target rate is positive. One might lament the shoe-leather costs during those periods, but it is a lament one could equally have in the current system. And over time, as central banks gain confidence that the zero lower bound is no more, they are likely to lower the target inflation rate, bringing shoe-leather costs during those periods at par down as well.

Tony’s second worry is that confidence will be shaken by the dramatic change in the system. He is certainly right that the formal models give little guidance on this point because under any fiat money system, the formal models allow the value of money to suddenly drop to zero at any time for no real reason. So any answer must be based solidly on intuitions about the real world rather than on a formal calculation.

Part of my reply to Tony’s second worry is to note that a straightforward arbitrage argument ensures that how the central bank treats paper currency at the cash window determines the value of paper currency relative to electronic money. (See An Underappreciated Power of a Central Bank: Determining the Relative Prices between the Various Forms of Money Under Its Jurisdiction.) So the danger at issue has to be something about all the forms of money controlled by the central bank put together.

But the main point I want to make is that the approach I recommend changes everything very gradually. At the moment of introducing the new system, paper currency starts at par, just as it is under the current system. Even at a quite low nominal interest rate of -4% per year, the value of paper currency relative to electronic money would only be changing by about 1.1 basis points per day. For example the exchange rate would go from 1000 electronic dollars per 1000 paper dollars on day zero to 999.89 electronic dollars per 1000 paper dollars the next day–an 11 cent paper currency deposit fee on $1000. The paper currency deposit fee on $1000 would escalate by roughly 11 cents each day, to 22 cents, then 33 cents, etc., until compounding kicked in a little more to make the absolute amount of the addition to the fee each day a little less. (Note that to fully establish the exchange rate, the paper currency deposit fee is levied on net deposits, meaning that on the day a deposit by a private bank at the Fed’s cash window of p$1000 would become e$999.89 in the bank’s reserve account, a withdrawal of p$1000 would only result in a deduction of e$999.89 from the bank’s reserve account. Or if the bank wanted to withdraw e$1000, it would receive something close to p$1000.11.)

Of course, 1.1 basis points per day adds up over time, so this is a big deal. My point is not to minimize the importance of what is being done with the exchange rate between paper currency and electronic money, but to say that the exchange rate is moving very gradually each day. There is plenty of time for people to get used to the new system. And the continuity from one day to the next means that for private agents, behaving more or less as they did yesterday is a viable option until they figure things out. By the time they figure things out, the system already has a track record of day after day looking stable.

All of the above is to argue that getting paper currency out of the way of negative interest rates will not cause any drastic change in behavior. The electronic negative interest rates themselves can and should cause a significant change in behavior–after all, the point is to stimulate the economy, as was needed in 2009 in the US, and as is needed now in the eurozone and in Japan. But I suspect that central banks will be fairly gradual in going to deeper negative rates as well. If the Swiss National Bank goes to deeper negative rates, for example, I will be surprised if the next step down from -.75% per year is to any lower than -1.25%. (And it is even more unlikely that the next step down would be to lower than -1.5%.)

Gradualism in going to deeper negative rates, (associated with gradualism in lower the paper currency interest rate to get paper currency out of the way) has costs in the slowness of the extra stimulus, but it tends to allay the kinds of worries that Tony is expressing. If the first step down in the paper currency interest rate is to -.5%, at that rate, after a full quarter, the paper currency deposit fee would only by 1/8 %, meaning that the exchange rate was .99875 electronic dollars per paper dollar after three months. That is nowhere near as disruptive as many other things central banks have done in the past, such as the sudden change in the exchange rate for the Swiss Franc back in January, 2015 (which I wrote of in my column “Swiss Pioneers! The Swiss as the Vanguard for Negative Interest Rates.”)

Leon Berkelmans: Time to Consider Negative Interest Rates to Boost Growth

I am grateful to Leon Berkelmans for securing permission from the Australian to mirror his article here, which appeared in the Australian on September 12, 2015.

Below, Leon mentions New Zealand as a monetary policy innovator that might adopt negative interest rates. On that, see also “Michael Reddell: The Zero Lower Bound and Miles Kimball’s Visit to New Zealand.”

The world waits, feverishly, for next week’s Federal Reserve meeting. The FOMC could increase interest rates for the first time in almost a decade. Martin Sandbu, of the Financial Times, called this decision “the single most important imminent economic policy decision in the world”. But there’s an even more important issue in plain sight. And we are not talking about it.

It’s the zero lower bound on interest rates. The Fed will be increasing interest rates from that bound, where rates have been stuck since the end of 2008. Other major economies are stuck at the zero lower bound too. Japan has been there for a couple of decades. The ECB hit the zero lower bound a few years after the Fed, but it’s there now, and unlikely to exit any time soon.

Some European central banks have been able to implement rates slightly below zero, showing that small negative returns will be tolerated, but there is a limit.

In any case, the zero lower bound has been costly. One analysis by Federal Reserve economists suggested that unemployment would have been 3 percentage points lower in 2012 had they been able to cut interest rates to negative 4 per cent.

One might adopt the position that the global financial crisis was a freak event. We haven’t seen such extremes in central bank interest rate policy before. Once economies exit the current situation, we are unlikely to see them again in the future. I think such a position is wrong.

In 2012, in their World Economic Outlook, the IMF documented the gradual but sustained and relentless decline in real long-term interest rates over the last three decades.

This decline in real long-term rates will translate to lower short-term nominal rates, on average, over the cycle. That means the zero lower bound is more likely to be hit. This is true, no matter where you are. Every economy is likely to face this new future.

There are several possible responses to these developments, among them: rely on unconventional monetary policy, raise the inflation target, pursue fiscal activist policy, implement institutional changes so that negative interest rates are possible, or change the monetary framework away from inflation targeting.

Unconventional monetary policy, namely quantitative easing and forward guidance, has probably had its successes. A different study by Federal Reserve economists has suggested that unconventional policies subtracted one and a quarter percentage points from the unemployment rate.

However, there is uncertainty about how unconventional policies work. For example, in 2012 Michael Woodford, the doyen of academic monetary economists, suggested that quantitative easing, in particular, did not have the effects typically ascribed to it.

Moreover, he claimed that unconventional policies often caused financial markets to become more pessimistic, an unsavoury side effect for a policy that’s supposed to be stimulatory. The debate and academic inquiry rages on, and more work will be needed before economists can claim to have mastered unconventional policy.

Raising the inflation target would help. Olivier Blanchard, outgoing chief economist at the IMF, and Janet Yellen, chair of the Federal Reserve, have openly mused about the possibility. But questions remain here too. How do you raise the target, and make the new target credible, given that the old target had been changed?

Activist fiscal policy could provide stimulus when interest rates are stuck at zero. Peter Tulip, of the Reserve Bank, last year pointed out how this would ameliorate the costs of the zero lower bound.

It’s again a possibility, but I think there are open questions about the alacrity of the political process. Could it always be relied upon to do enough?

Changes could be implemented to make significant negative interest rates feasible. Ken Rogoff, a former IMF chief economist, has discussed the possibility of abolishing physical currency, which would do the trick. Moving away from an inflation target, towards something like nominal GDP targeting, could also work. Michael Woodford offered this as an alternative in the same 2012 paper I mentioned earlier. However, there are some shortcomings, especially in a small open economy like Australia, where a volatile terms of trade can play havoc with nominal GDP growth.

I’m not sure any solution is perfect. However, central banks should plan ahead. It’s unlikely that the future will look like the pre-GFC past. Planning on that basis will lead to tears and leave a guilty central bank looking jealously at an innovator that took the issue head on — perhaps an innovator like, gasp, New Zealand.

Leon Berkelmans is director, international economy, at the Lowy Institute for International Policy.

Bank of England Chief Economist Andrew Haldane Explains How to Break Through the Zero Lower Bound

Some of the reporting of Andrew Haldane’s September 18 speech “How low can you go?” skipped over key things he said. Here is the part of his speech where he explains how to break through the zero lower bound:

Negative interest rates on currency

That brings me to the third, and perhaps most radical and durable, option. It is one which brings together issues of currency and monetary policy. It involves finding a technological means either of levying a negative interest rate on currency, or of breaking the constraint physical currency imposes on setting such a rate (Buiter (2009)).

These options are not new. Over a century ago, Silvio Gesell proposed levying a stamp tax on currency to generate a negative interest rate (Gesell (1916)). Keynes discussed this scheme, approvingly, in the General Theory. More recently, a number of modern-day variants of the stamp tax on currency have been proposed – for example, by randomly invalidating banknotes by serial number (Mankiw (2009), Goodfriend (2000)).

A more radical proposal still would be to remove the ZLB constraint entirely by abolishing paper currency. This, too, has recently had its supporters (for example, Rogoff (2014)). As well as solving the ZLB problem, it has the added advantage of taxing illicit activities undertaken using paper currency, such as drug-dealing, at source.

A third option is to set an explicit exchange rate between paper currency and electronic (or bank) money. Having paper currency steadily depreciate relative to digital money effectively generates a negative interest rate on currency, provided electronic money is accepted by the public as the unit of account rather than currency. This again is an old idea (Eisler (1932)), recently revitalised and updated (for example, Kimball (2015)).

All of these options could, in principle, solve the ZLB problem. In practice, each of them faces a significant behavioural constraint. Government-backed currency is a social convention, certainly as the unit of account and to lesser extent as a medium of exchange. These social conventions are not easily shifted, whether by taxing, switching or abolishing them. That is why, despite its seeming unattractiveness, currency demand has continued to rise faster than money GDP in a number of countries (Fish and Whymark (2015)).

One interesting solution, then, would be to maintain the principle of a government-backed currency, but have it issued in an electronic rather than paper form. This would preserve the social convention of a state-issued unit of account and medium of exchange, albeit with currency now held in digital rather than physical wallets. But it would allow negative interest rates to be levied on currency easily and speedily, so relaxing the ZLB constraint.

Would such a monetary technology be feasible? In one sense, there is nothing new about digital, state-issued money. Bank deposits at the central bank are precisely that.

Alex Rosenberg Interviews Miles Kimball for CNBC: Could Negative Interest Rates Be Next on the Fed’s Policy Menu?

Here is a link to Alex Rosenberg’s distillation of his interview with me about negative interest rate policy (if you ignore the video at the top and focus on the words beneath that). He did a great job of representing our wide-ranging conversation in a compact way. (In the interview, I did give other economists, especially Willem Buiter, more credit for working out the key ideas for eliminating the zero lower bound than Alex indicated; it is a standard journalistic trope to simplify the story of collective efforts to make it sound like the work of one individual.)

I found one error, or at least misleading bit, in the article. It says:

At the same time, the government would have to remove the requirement that businesses accept cash as legal tender.

This is a common misconception about legal tender. For the most part, “legal tender” laws only affect the treatment of debt. Except perhaps in a few states, shopkeepers are legally allowed to refuse payment in cash. (On many plane flights I have been on recently, they have announced that they would only accept payment by credit or debit card, for example.)

Here is the explanation from the US Treasury website about legal tender (found with the help of my brother Chris Kimball):

The pertinent portion of law that applies to your question is the Coinage Act of 1965, specifically Section 31 U.S.C. 5103, entitled “Legal tender,” which states: “United States coins and currency (including Federal reserve notes and circulating notes of Federal reserve banks and national banks) are legal tender for all debts, public charges, taxes, and dues.”

This statute means that all United States money as identified above are a valid and legal offer of payment for debts when tendered to a creditor. There is, however, no Federal statute mandating that a private business, a person or an organization must accept currency or coins as for payment for goods and/or services. Private businesses are free to develop their own policies on whether or not to accept cash unless there is a State law which says otherwise. For example, a bus line may prohibit payment of fares in pennies or dollar bills. In addition, movie theaters, convenience stores and gas stations may refuse to accept large denomination currency (usually notes above $20) as a matter of policy.

This means that adjusting “legal tender” itself, while desirable, is less crucial for the type of policy I am recommending. The legal tender issue for debts can be handled by putting appropriate clauses in debt contracts, if lawyers wake up. For payments to the government, legal tender is also an issue, but I think once people started showing up at the IRS with suitcases full of cash, the government would quickly fix that loophole.

Update: In response to my questioning of this passage, Alex corrected it to “At the same time, the government could not require that businesses accept cash as legal tender.”

Here I would say that it is important that businesses not be required to accept cash as legal tender for large-ticket durables and investment goods; it causes less trouble if the government requires businesses to accept cash for goods that people typically use cash for now (indeed, I have argued that businesses might in any case voluntarily continue to accept cash at par for a long time even in the absence of any government constraint), and below-par cash as legal tender for debts, while an undesirable side effect, does not create a zero lower bound, since one cannot get an unlimited supply of new debt contracts on the same terms as old debt contracts.

For the First Time, Someone on the US Monetary Policy Committee Is Recommending a Negative Target Rate

Look at the two dots below zero showing the idea that negative rates should start now and continue into 2016. Thanks to Leon Berkelmans for pointing this out.

Bleg: Do I need to change my title? Has this happened before?

For those who want to get some evidence of causality between awareness of how easy it is to break through the zero lower bound and leaning toward negative rates, see the schedule of my travels so far to talk about eliminating the zero lower bound here.

An Underappreciated Power of a Central Bank: Determining the Relative Prices between the Various Forms of Money Under Its Jurisdiction

Any unlimited opportunity to lend to the government at a zero interest rate creates a zero lower bound. In practice, when currency regions have gone to negative interest rates, as Switzerland, Denmark, Sweden and the euro zone have, they have lowered their interest rates on reserves, so it is the unlimited opportunity to lend to the government at a zero interest rate by withdrawing paper currency from the bank that seems to be the toughest issue.

The opportunity to lend to the government at a zero interest rate by prepaying taxes is another interesting issue. but as my brother Chris and I argued in “However Low Interest Rates Might Go, the IRS Will Never Act Like a Bank,” for the US at least, it is a limited one, unless the Secretary of Treasury intends to subvert the negative interest rate policy. Once one is paying all one’s taxes at the beginning of the tax year, there is no further available arbitrage on that front, since the between-year tax rate is by law supposed to be set by the Secretary of the Treasury in line with other short-term interest rates.

How can a central bank keep people from shifting their money into paper currency when interest rates are negative? The long answer can be found in all the links in my bibliographic post “How and Why to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound: A Reader’s Guide.” The short answer can be found in the CEPR’s 5-minute interview with me:

The basic idea depends on one of the roles of central banks that many “Money and Banking” textbooks fail to mention: the role of determining how much, among all the forms of money under its jurisdiction, each type is worth compared to the others. Let me use the example of Japan, since I thought about this issue in the context of writing “Is the Bank of Japan Succeeding in Its Goal of Raising Inflation?” and “Japan Should Be Trying Out a Next-Generation Monetary Policy” last week. Ultimately, it is not the numbers “10000” and “1000” written on them that make a ten-thousand-yen note equal in value to ten one-thousand-yen notes—it is the fact that the Bank of Japan is willing to freely convert a ten-thousand-yen note into ten one-thousand-yen notes and vice versa. Such conversions happen at a part of the central bank so underappreciated that some central bankers don’t even know where it is: the cash window.

It Isn’t the Face Value that Determines How Much Each Type of Paper Currency is Worth. To see this role of a central bank clearly, consider a case where not only direct access to the central bank, but access to the banking system in general is problematic: the criminal underworld. Think of the standard scene in American mob movies in which the mobster demands a suitcase full of cash in tens and twenties. Why tens and twenties? Using the banking system often increases the chance that a criminal will get caught. Money can be laundered, but it is easier to launder tens and twenties. So, at least near the point of money laundering, ten ten-dollar bills are worth more than one hard-to-launder hundred-dollar bill. That means that if you bring me a suitcase full of one-hundred dollar bills with the same face value as a suitcase full of tens and twenties, you are bringing me less value—you have cheated me.

The Exchange Rate Between Paper Currency and Electronic Money. Just as central banks determine the relative value of different denominations of paper currency by how they treat them at the cash window, they also determine how much paper currency is worth compared to electronic money in a reserve account by how they treat the paper currency at the cash window. A reserve account here is a private bank’s bank account with the central bank; for the Bank of Japan, the balance in a reserve account is a number in the Bank of Japan’s computer system. If the Bank of Japan treated a paper 1000-yen note as worth 990 electronic yen, that is what it would be worth. Here is what it means to treat a 1000-yen note as worth 990 electronic yen: (a) when a private bank came to the cash window of the Bank of Japan and hands in a paper 1000-yen note to have the money put into its reserve account the Bank of Japan would add only 990 yen to that private bank’s reserve account; (b) when a private bank came to the cash window of the Bank of Japan and asked for a paper 1000-yen note, only 990 yen would be deducted from its reserve account.

By the phrase “forms of money under its own jurisdiction” I mean forms of money that a central bank has the authority to print or otherwise create in unlimited quantities. If a central bank can create unlimited quantities of two forms of money, it can commit to exchange one form for the other at any exchange rate it declares without any reason to worry that it won’t be able to provide the form a bank wants to change another form of money under its authority into. In other words, the central bank has unlimited firepower for defending any exchange rate it declares between different forms of money under its jurisdiction. Moreover, an exchange of one form of money for another at a declared exchange rate does not, in itself, directly change the quantity of high-powered money under the central bank’s jurisdiction (though altering the exchange rate between different forms of money may).

To emphasize, a central bank can easily defend any exchange rate it declares between paper currency and electronic money–just as, say, the Fed can easily defend the exchange rate between $20 bills and $10 bills–since it has the authority to create as much of either one that banks want to change the other into.

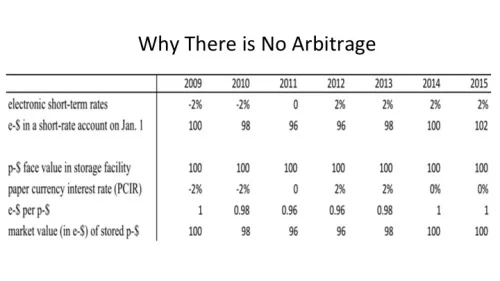

Using the Exchange Rate Between Paper Currency and Electronic Money to Create a Non-Zero Paper Currency Interest Rate. Once a central bank uses it power to determine the relative price of different forms of money under its jurisdiction in earnest, it is straightforward to insure that there is no way to circumvent negative interest rates by storing paper currency. Consider this slide from my presentation “18 Misconceptions about Eliminating the Zero Lower Bound”:

In this example contemplating an alternate history, the central bank has a -2% target rate for two years: 2009 and 2010. To get anything close to a -2% market equilibrium interest rate, the central bank must also reduce it interest rate on reserves to something close to zero. And it needs to reduce its paper currency interest rate to something closer to -2% than to 0. How can it do that? $100 will still have a $100 face value no matter how long it is stored (until cash physically disintegrates). But its market value is determined by how that paper currency with a face value of $100 is treated at the cash window of the central bank. If the central bank treats it as 100 electronic dollars on January 1, 2009, gradually decreasing to 98 electronic dollars on January 1, 2010, and to 96 electronic dollars on January 1, 2011, the rate of return of that paper currency will be -2% per year throughout 2009 and 2010. The idea is to match the paper currency interest rate to the target rate. (One could have a small spread relative to the target rate–say .5% in either direction without causing too much trouble, but the example is simplest if the target paper currency spread is zero.) To match the paper currency interest rate to the 0 target rate in 2011, the central bank need to treat the $100 face value worth of paper currency as $96 electronic throughout 2011. Then with the target rate equal to +2% per year in 2012 and 2013, the central bank can gradually bring the value of the $100 in face value of paper currency back up to being worth $100 electronic around January 1, 2014.

Where the Magic Is. How can an exchange rate between paper currency and electronic money avoid arbitrage without elaborate tracking of each paper note? It is because the rate of change of the exchange rate automatically keeps track of the cumulative paper currency interest rate over the time the paper currency is in private hands–and the paper currency interest rate (really a capital gains rate) is kept equal to the target rate. To reemphasize, it is not the level of the exchange rate between paper currency and electronic money that does the magic, but the rate of change. Just as a sundial keeps track of how much time has passed by how far the shadow has moved, the exchange rate between paper currency and electronic money keeps track of the cumulative interest on paper currency by how far it has moved.

Another Applications of a Central Bank’s Power to Determine the Relative Price of Different Currencies Under Its Jurisdiction: the Electronic Mark.

We are used to thinking of each central bank as having one currency. But it is quite possible for a single institution to supervise more than one currency. I explore the possibilities of a possibility that changes an international exchange rate in conjunction with the exchange rate between paper currency and electronic money in my column “How the Electronic Deutsche Mark Can Save Europe.” The reintroduction of a paper Deutsche Mark would be likely to create immediate, serious problems. The introduction of a purely electronic German mark would work well. In general, when the straightjacket of a single currency becomes too tight, it causes fewer problems to split off a strong currency in electronic form, rather than splitting off a weak currency (as in the worry over Grexit and the reintroduction of the Greek drachma, narrowly averted for now).

The Negative Zones

I often have occasion to say that I have presented my proposal for eliminating the zero lower bound all around the world. I give the full list of where I have given talks on eliminating the zero lower bound in “Electronic Money: The Powerpoint File.” To see how literal that statement can be taken, I wanted to tally up how many time zones I can account for, only counting presentations at central banks and their branches. I intend to keep this updated as I add additional time zones.

Here they are, in the order of sunrise on a particular calendar date, with the first date listed when I have been to more than one central bank or branch of a central bank in that time zone. Note that UTC 0 is the same as Greenwich Mean Time.

- UTC+12: Reserve Bank of New Zealand, July 22, 2015

- UTC+9: Bank of Japan, June 18, 2013

- UTC+7: Bank of Thailand, September 29, 2016

- UTC+3: Qatar Central Bank (This was in Education City, off-site from the central bank itself, but a central bank official was my discussant.)

- UTC+2: Bank of Finland, May 20, 2015

- UTC+1: National Bank of Denmark, September 6, 2013

- UTC 0: Bank of England, May 20, 2013

- UTC-5: Federal Reserve Board, November 1, 2013

- UTC-6: Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, September 3, 2015

To put this in perspective, let me point out that some time zones are not as well provided with central banks and central bank branches as other time zones! But other time zones I hope to add soon.

Is the Bank of Japan Succeeding in Its Goal of Raising Inflation?

image source

On June 29, 2012, I posted “Future Heroes of Humanity and Heroes of Japan,” advocating just the sort of massive asset purchases the Bank of Japan has undertaken. Although I now think that using deep negative interest rates after eliminating the zero lower bound is a far superior policy, I am still interested to see how well massive quantitative easing has worked.

Japan’s GDP shrank by .4% in the 2d quarter of 2015. It is now slightly below the level it had in the first quarter of 2008, although with the shrinking of the Japanese population, per capita GDP is up about 1% since the first quarter of 2008. Overall, Japan has managed to clamber back up from blows of the Great Recession, but can it achieve sustained, robust economic growth?

Japan's Real GDP

Source: Cabinet Office of Japan. Real GDP shown as the logarithmic percentage above the GDP peak in the first quarter of 2008.

The remarkable Japanese election in December 2012 put Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in charge, and induced a major change in monetary policy, as the Bank of Japan under Governor Haruhiko Kuroda embarked on a program of quantitative easing on steroids, committing to buying bonds and other securities equal in value to over half of GDP every year.

Prices of Key Components of Japan’s GDP

Source: Cabinet Office of Japan. Deflators for components of Real GDP shown as the logarithmic percentage above the price peak in the third quarter of 2008.

“Abenomics” seems to have had an effect. One of the key objectives for monetary policy has been to turn deflation into inflation of 2%. The quarter before Abe’s election was the low point for prices. Since the third quarter of 2012, consumption prices (blue), house construction prices (red) and business investment prices (green) have been on an upward track. Both the consumption prices and residential investment prices have a big jump up between the first and second quarter of 2014 due to Japan’s big sales tax increase. That jump due to the sales tax increase says nothing about whether or not monetary policy is working, so the upward trend in consumption prices is quite unimpressive. But because business spending is exempt from sales taxes, the business investment prices are unaffected by the sales tax increase; business investment prices show a steady increase since Abe was elected.

The steady increase in business investment prices, and volatile upward trend of house construction prices are important because the reason Japan wants to have more inflation is that when businesses build a factor or buy a machine, or someone builds a house, they are comparing the interest rate they have to pay to how fast the value of their investment or house will go up with time—of which inflation is an important component. And the price trends that matter for such investment decisions are the price trends for residential investment and business investment. (Indeed, Bob Barsky, Chris Boehm, Chris House and I have an early stage working paper arguing that for this reason central banks should pay much more attention to investment goods prices than they do.)

One way of seeing how well Japan has turned around its price trends is look at Japanese inflation compared to US inflation. In the graph below, a flat line would mean that Japanese inflation was equal to US inflation. Even after correcting for the sales tax increase, since Prime Minister Abe’s election late in 2012, inflation for consumption and business investment don’t look that different in Japan than in the US, and the lower inflation for residential investment reflects relatively high inflation for that component of GDP in the US rather than a lack of inflation in Japan.

Japanese Price Trends Compared to US Price Trends

Source: Cabinet Office of Japan. Deflators for components of Japan’s Real GDP shown as the logarithmic percentage above the price peak in the third quarter of 2008 minus the logarithmic percentage of the corresponding US prices above their level in the third quarter of 2008.

Japan’s Performance is Still Substandard. So far, this sounds like a rosy picture. But it isn’t. A stagnant economy is a bad outcome. And even if Japan’s current inflation trends continue, they still don’t make a zero interest rate low enough in comparison to set off the investment boom that is needed to jump-start the Japanese economy. After all, the US inflation statistics used as a point of reference for Japan’s above don’t give the Fed that much room to maneuver under current policy parameters either.

How Japan Can Get Out of Its Bind. What Japan needs is an even more dramatic shift in its monetary policy: deep negative interest rates.

In a recent Quartz column, I talk about the growing acceptance of the idea that the so-called “zero lower bound” or “effective lower bound” on interest rates can be eliminated. In particular, a time-varying paper currency deposit fee on net deposits at the cash window of a central bank can make it possible to cut interest rates as low as needed, without having to worry about people hoarding paper currency. The secret is that the central bank is promising to convert money in the bank into more and more paper currency in the future—at a more than 1-for-1 exchange rate, so storing cash is a worse deal than taking a negative interest rate in the bank but then being able to convert those funds into cash at a favorable exchange rate in the future. If interest rates later turn positive, this process can be reversed, or if necessary, it can go on indefinitely. I have personally visited central banks all over the world explaining such an approach, and take care to explain to central bank staffers and decision-makers how smoothly this can work.

When I visited the Bank of Japan in June 2013 to explain how to eliminate the zero lower bound on interest rates and use deep negative rates to revive the Japanese economy, the Bank of Japan wasn’t ready. Given the partial success that they have had with massive quantitative easing, and the dramatic election results it took to get to that far, I still don’t think don’t think the Bank of Japan is ready for deep negative interest rates. But that is the first step on Japan’s road back to a vibrant economy.

Wall Street Journal Off Track: Jon Hilsenrath and Nick Timiraos Report As If the “Effective Lower Bound” Were a Law of Nature

To their credit, in their August 17, 2015 Wall Street Journal article “U.S. Lacks Ammo for Next Economic Crisis” Jon Hilsenrath and Nick Timiraos talk about negative interest rates as a potential policy tool, writing at different points:

- The Fed, for example, could experiment with negative interest rates.

- Mr. Bernanke said he was struck by how central banks in Europe recently pushed short-term interest rates into negative territory, essentially charging banks for depositing cash rather than lending it to businesses and households. The Swiss National Bank, for example, charges commercial banks 0.75% interest for money they park, an incentive to lend it elsewhere. Economic theory suggests negative rates prompt businesses and households to hoard cash—essentially, stuff it in a mattress. “It does look like rates can go more negative than conventional wisdom has held,” Mr. Bernanke said.

Yet although they reflect the evolution of the zero lower bound (still a handy name) into what many central banks are now calling the “effective lower bound,” which is somewhat below zero, Jon and Nick do nothing to inform their readers that cash hoarding can be avoided by the simple expedient of a time-varying paper currency deposit fee at the cash window of a central bank that creates an exchange rate between paper currency and electronic money, which can then lower the yield on paper currency by allowing it to very slowly depreciate against electronic money. (As a terminological note, I should say that most of the time I will continue to use the phrase “zero lower bound” rather than “effective lower bound,” since I think the big shift is to break through the zero lower bound on the nominal interest rate for paper currency–which then removes any effective lower bound on other interest rates as long as the full set of interest rates the central bank then controls are moved in tandem.)

The article also gives a misleading impression with its subtitle, “Policy makers worry fiscal and monetary tools to battle a recession are in short supply” and an unnuanced picture caption saying

U.S. Defenses Down: The Federal Reserve will have fewer monetary weapons in the next recession. It has less room to cut rates, and its swollen portfolio will make it harder to launch new rounds of bond buying.

If the Fed has fewer monetary weapons in the next recession, it will be only because either legal barriers or timidity leave it fewer monetary weapons. The Fed knows how to break through the “effective lower bound” ever since my seminar there on November 1, 2013. (I also gave a seminar at the New York on October 15, 2014 and I am slated to give a seminar at the Chicago Fed at the beginning of September 2015.)

Of course, Jon and Nick are not the only ones off target. I am sure that they are correct in reporting

Others, including Sen. Bob Corker (R.,Tenn.), see only the Fed’s limits. “They have, like, zero juice left,” he said.

Many economists believe relief from the next downturn will have to come from fiscal policy makers not the Fed, a daunting prospect given the philosophical divide between the two parties.

But I am confident that many more economists (as well as senators) would realize how much more the Fed and other central banks can do if the Wall Street Journal would report on the work being done on ways to break through the “effective lower bound.” To that end, I sent an email to Jon (whom I have corresponded with on occasion in the past) that I am copying out here as an open letter, after very light editing:

Dear Jon,

I wanted to write because I think the title of today’s column is simply false–and the real story is much more interesting. I said much the same thing about a recent Economist column in Quartz:

Radical Banking: The World Needs New Tools to Fight the Next Recession

You have probably been following my work on negative interest rates to some extent. I have the things I have written on that collected here,

How and Why to Eliminate the Zero Lower Bound: A Reader’s Guide

and my academic paper with Ruchir Agarwal on it is coming soon.

Central banks are well aware of the fact that it is not that hard to break through the zero lower bound, if only because of my extensive travels to tell them about it, listed in my post

Electronic Money: The Powerpoint File.

Thinking about this sort of thing is what is happening under the surface at many central banks.

Jennifer Ryan on Andrew Haldane: "The UK’s Subversive Central Banker" →

Unlike Bank of England Chief Economist Andrew Haldane’s position described in Jennifer Ryan’s Bloomberg Business article linked above, I am doubtful that the UK needs lower interest rates right now. But if it did, Andrew Sentance, a former member of the Bank of England’s monetary policy committee is wrong in saying “There’s not much lower you can go, and a cut to 0.25 percent isn’t going to have a significant impact on the economy” (as quoted in the article). The Bank of England has actually been quite interested in eliminating the zero lower bound, as indicated by making Ken Rogoff and me keynote speakers at their conference on the future of money in May 2015.