Steve Silberman: Placebos Are Getting More Effective. Drugmakers Are Desperate to Know Why →

Thanks to Diana Kimball for pointing me to this link.

The Economist: Taking the Bother Out of Birth Control →

This is a valuable article in the Economist about a topic that many Americans (including me) often find it a bit awkward to talk about: birth control. Implants and IUDs (intrauterine devices) have moved far beyond the Dalkon shield that hurt their reputation in the 1970s. Standard guidelines say that “providers should mention them first, before the less effective options,” but many doctors and other providers don’t realize this.

Exploiting the underused technology of implants and IUDs can do a lot to reduce the teen pregnancy rate. From the article:

In Colorado in 2009 a private foundation started paying both for IUDs and implants in public clinics and for training the staff who provide them. Within two years teenage births fell by 26% and abortions by 34% (both were down in other age groups, too).

Because many of these teenagers can’t support kids without help from the state, doing this saves a lot more public money than the money put in.

Tina Rosenberg: A Psychological Depression-Fighting Strategy That Could Go Viral →

I love to see technological progress. Technological progress in mental health care is especially welcome. Tina Rosenberg discusses an approach that seems to be both effective and affordable.

To lower the cost of treating depression in the US, the key policy issue is to make sure that certification and licensing for this kind of counseling is kept inexpensive. We need to keep psychologists from erecting barriers to entry just to protect their market position.

Clay Christensen, Jerome Grossman and Jason Hwang: How to Divide and Conquer Our Health Care Problems

As I discussed in my post “Clay Christensen, Jerome Grossman and Jason Hwang on the Three Basic Types of Business Models,” Clay Christensen and his coauthors in all his business strategy books use a model of three basic types of business models:

- solution shops

- value-added processing (VAP)

- facilitated networks.

In The Innovator’s Prescription (location 375), Clay Christensen, Jerome Grossman and Jason Hwang point out how these different types of business models default to different types of payment structures. Adding some headings:

Solution Shops

Payment almost always is made to solution shop businesses in the form of fee for service. We’ve observed that consulting firms such as Bain and Company occasionally agree to be paid in part based upon the results of the diagnosis and recommendations their teams have made. But that rarely sticks, because the outcome depends on many factors beyond the correctness of the diagnosis and recommendations, so guarantees about total costs and ultimate outcomes can rarely be made. …

Value Added Processing

VAP businesses typically charge their customers for the output of their processes, whereas solution shops must bill for the cost of their inputs. Most of them even guarantee the result. They can do this because the ability to deliver the outcome is embedded in repeatable and controllable processes and the equipment used in those processes. Hence, restaurants can print prices on their menus, and universities can sell credit hours at guaranteed prices. Manufacturers of most products publish their prices and guarantee the result for the period of warranty.

Since they operate in the realms of empirical and precision medicine, VAP businesses in the health-care industry can do the same thing. MinuteClinic posts the prices of every procedure it offers. Eye surgery centers advertise their prices; and Geisinger’s heart hospitals can specify in advance not just the price of an angioplasty procedure, but can guarantee the result. In a new and remarkable agreement with several European governments, Johnson & Johnson has guaranteed that its new drug Velcade will effectively treat a specific form of multiple myeloma that can be diagnosed with a particular biomarker—or it will refund to the health ministry the cost of the full course of therapy. J&J can do this because the treatment is undertaken after a definitive diagnosis has been made. …

Facilitated Networks

Facilitated network business models in health care can be structured to make money by keeping people well; whereas solution shop and VAP business models make money when people are sick.

In particular, facilitated networks often work on some kind of subscription or annual fee for payment.

Clay, Jerome and Jason argue that there are two key steps to making health care less expensive:

- separating out the components of health care according to the most appropriate type of business model, and

- developing better ways of doing things within each category, building on that higher level of focus within each part of health care.

Here is how they say it (with my headings):

The need to separate out components of health care according to appropriate business model:

Many who have written about the problems of health care decry the fact that the value of health-care services being offered by hospitals and doctors is not being measured. To them, we would explain that the reason isn’t that these providers don’t want to provide measurable value; they simply can’t, because under the same roof they have conflated fundamentally different business models whose metrics of output, value, and payment are incompatible with one another. …

Using the clear metrics within each category of health care to innovate further:

The reason why this basic segregation of business models must occur from the outset of disruption is that it will enable accurate measurements of value, costs, pricing, and profit for each type of business. A second wave of disruptive business models can then emerge within each of these three types. Powerful online tools can walk physicians through the process of interpreting symptoms and test results to formulate hypotheses, then help them define the additional data they need to converge upon definitive diagnoses. This will enable lower-cost primary care physicians to access the expertise of—and thereby disrupt—specialist practitioners of intuitive medicine. Likewise, ambulatory clinics will disrupt inpatient VAP hospitals. Retail providers like MinuteClinic, which employ nurse practitioners rather than physicians, need to disrupt physicians’ practices.

Avoiding the trap of thinking everything needs to be done in the solution shop business model:

Hospitals and physicians’ practices have long defended themselves under the banner, “For the good of the patient.” Yet, for the good of the patient, do we really need to leave all care in the realm of intuitive medicine? Much technology has moved past this point, and health-care business models need to catch up. Two landmark reports from the Institute of Medicine—Crossing the Quality Chasm and To Err Is Human—shattered the myth that ever-escalating cost was the price Americans must pay to have the high-quality care that only full-service hospitals staffed by the best doctors can provide.

I find Clay, Jerome and Jason’s indictment of our current health care system as mixing together care appropriate to different business models trenchant. I wish this insight made it into more of the commentary about health care reform.

You can see the rest of my posts tagged “Clay Christensen” here.

Why Economic Theory Predicts a Chronic Shortage of Nurses

The word “shortage” says more than you might realize. A shortage is when there is too little of something to clear the market at the going price. Thus, a shortage is a sign that the price is too low to clear the market. Usually, this is a temporary situation: the price adjusts upward and people quit complaining about a shortage and start complaining about high prices instead.

There are two general situations in which a price might be too low to clear the market for a long period of time. One case is when the government imposes a price ceiling. For example, rent control leads over time to a chronic shortage of apartments.

The other general situation in which a price is chronically too low to clear the market is when there is only one big buyer or only a few big buyers in the relevant market. Having only one buyer is called monopsony. Having only a few buyers is called oligopsony.

In any local commuting area, there are typically only a few hospitals, that account for a large share of all nursing employment–particularly for the higher-skill, higher-paid nursing jobs. Because each hospital is big enough to affect the wage in the local labor market, it worries about driving up the wage of nurses by hiring too many. That is, the cost of the last nurse a hospital hires is not just the wage of that one nurse, but also the cost of the rise in the wage to all the other nurses it employs due to that extra hiring.

In other words, the hospital might be willing to pay a little extra to get one more nurse who is a little more reluctant to come back into the labor force, say, except that paying that higher wage to the one nurse would force it to pay more to all of its other nurses.

Why doesn’t the same logic cause a doctor shortage? It is because doctors operate in a national labor market. Doctors make enough money that it is worthwhile for them to consider moving to other cities at some distance in order to take advantage of a modest percentage difference in pay. By contrast, nurses are often secondary earners in their families and so tied to one commuting area, or even when they are free agents,they make little enough money that the cost of moving to a whole new region to make a few percent more doesn’t seem very attractive.

Someone might object to my account of where chronic nursing shortages come from by saying it is a problem of too few spots available in programs that train nurses. Too few spots in programs training nurses would indeed reduce the supply of nurses, but should lead to complaints about nurses being expensive rather than complaints about a shortage of nurses. Yet for some reason, there are a lot more complaints about nurse “shortages” than about how expensive nurses are.

The blue line is the frequency of the phrase “nurse shortage” in ngram viewer. The red line is the frequency of the phrase “expensive nurses."

Clay Christensen, Jerome Grossman and Jason Hwang on the Three Basic Types of Business Models

In The Innovator’s Prescription, Clay Christensen, Jerome Grossman and Jason Hwang make good use of a typology of business models laid out by C. B. Stabell and Øystein Fjeldstad in their May, 1998 Strategic Management Journal article “Configuring Value for Competitive Advantage: On Chains, Shops and Networks.” Modifying Stabell and Fjeldstad’s terminology a bit for clarity, Clay and his coauthors call the three types of business models solutions shops, value-adding processes, and facilitated networks. Clay, Jerome and Jason argue that these three types of business models are so different that it is difficult to efficiently house them under one roof. They give these definitions for these three types of business models (from about location 360):

Solution Shops

These “shops” are businesses that are structured to diagnose and solve unstructured problems. Consulting firms, advertising agencies, research and development organizations, and certain law firms fall into this category. Solution shops deliver value primarily through the people they employ—experts who draw upon their intuition and analytical and problem-solving skills to diagnose the cause of complicated problems. After diagnosis, these experts recommend solutions. Because diagnosing the cause of complex problems and devising workable solutions has such high subsequent leverage, customers typically are willing to pay very high prices for the services of the professionals in solution shops.

The diagnostic work performed in general hospitals and in some specialist physicians’ practices are solution shops of sorts. …

Value-Adding Processes

Organizations with value-adding process business models take in incomplete or broken things and then transform them into more complete outputs of higher value. Retailing, restaurants, automobile manufacturing, petroleum refining, and the work of many educational institutions are examples of VAP businesses. Some VAP organizations are highly efficient and consistent, while others are less so.

Many medical procedures that occur after a definitive diagnosis has been made are value-adding process activities….

Facilitated Networks

These are enterprises in which people exchange things with one another. Mutual insurance companies are facilitators of networks: customers deposit their premiums into the pool, and they take claims out of it. Participants in telecommunications networks send and receive calls and data among themselves; eBay and craigslist are network businesses. In this type of business, the companies that make money tend to be those that facilitate the effective operation of the network. They typically make money through membership or user fees.

Networks can also be an effective business model for the care of many chronic illnesses that rely heavily on modifications in patient behavior for successful treatment. Until recently, however, there have been few facilitated network businesses to address this growing portion of the world’s health-care burden. …

Clay, Jerome and Jason’s central idea is that medicine will be more efficient if there is one medical institution designed for inherently expensive “solution shop” activities such as difficult diagnoses, other much more convenient and inexpensive clinics for the routine treatment of well-diagnosed diseases, and online networks for patients to discuss their contribution as patients to disease management with others who have the same disease. What wouldn’t survive would be the current hospital model where the solution shop aspect of what they do confers high expense on many other activities that don’t have to be so expensive. Here is the way Clay, Jerome and Jason say it:

The two dominant provider institutions in health care—general hospitals and physicians’ practices—emerged originally as solution shops. But over time they have mixed in value-adding process and facilitated network activities as well. This has resulted in complex, confused institutions in which much of the cost is spent in overhead activities, rather than in direct patient care. For each to function properly, these business models must be separated in as “pure” a way as possible.

This is not just a matter of static efficiency:

The health-care system has trapped many disruption-enabling technologies in high-cost institutions that have conflated two and often three business models under the same roof. The situation screams for business model innovation. The first wave of innovation must separate different business models into separate institutions whose resources, processes, and profit models are matched to the nature and degree of precision by which the disease is understood. Solution shops need to become focused so they can deliver and price the services of intuitive medicine accurately. Focused value-adding process hospitals need to absorb those procedures that general hospitals have historically performed after definitive diagnosis. And facilitated networks need to be cultivated to manage the care of many behavior-dependent chronic diseases. Solution shops and VAP hospitals can be created as hospitals-within-hospitals if done correctly.

Further Musings: Even apart from this application to health care, I have found the typology of solution shop, value-adding process and facilitated network very interesting to think about for understanding my own work life (as a complement to the kind of analysis I talked about in my post “Prioritization”).

I work at the University of Michigan. Universities combine research–which is quintessentially a solution shop activity–with teaching, which has a big component of value-adding processes. And of course, Tumblr, Twitter and Facebook, where I put in effort as a blogger, are facilitated networks.

The idea of a value-adding process highlights the gains to be had from routinizing something. It is good to periodically ask oneself if there is anything in my daily activities that I can make more routine and streamlined.

The idea of a facilitated network highlights the gains to be had by having users do a lot of the work. That in turn is related both to the benefits of laissez faire under a decent system of rules and the idea of delegation, which typically involves giving up some control at the detailed level.

I find for me, however, that I love the “solution-shop” aspect of life so much that I think I resist routinization. I don’t know if this is what I should be doing, but I would rather keep thinking about how I am doing things than have everything fade into the background of routine. That does cost me extra time, as I do things inefficiently because I am thinking too much about them as I do them.

Here is a link to a sub-blog of all of my posts tagged as being about Clay Christensen’s work

Clay Christensen, Jerome Grossman and Jason Hwang on Intuitive Medicine vs. Precision Medicine

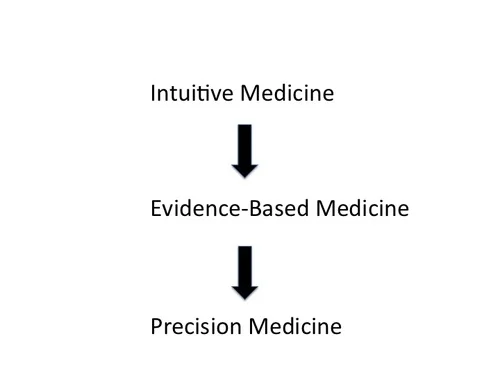

I found the passage below from The Innovator’s Prescription (location 333), by Clay Christensen, Jerome Grossman and Jason Hwang especially insightful. It puts diagnosis at the center of medicine, especially when viewing medicine from a business point of view. Better and better diagnosis opens up the possibility of more cost-efficient treatments for those diseases that are precisely identified. But that possibility must be seized.

Our bodies have a limited vocabulary to draw upon when they need to express that something is wrong. The vocabulary is comprised of physical symptoms, and there aren’t nearly enough symptoms to go around for all of the diseases that exist—so diseases essentially have to share symptoms. When a disease is only diagnosed by physical symptoms, therefore, a rules-based therapy for that diagnosis is typically impossible—because the symptom is typically just an umbrella manifestation of any one of a number of distinctly different disorders.

The technological enablers of disruption in health care are those that provide the ability to precisely diagnose by the cause of a patient’s condition, rather than by physical symptom. These technologies include molecular diagnostics, diagnostic imaging technology, and ubiquitous telecommunication. When precise diagnosis isn’t possible, then treatment must be provided through what we call intuitive medicine, where highly trained and expensive professionals solve medical problems through intuitive experimentation and pattern recognition. As these patterns become clearer, care evolves into the realm of evidence-based medicine, or empirical medicine—where data are amassed to show that certain ways of treating patients are, on average, better than others. Only when diseases are diagnosed precisely, however, can therapy that is predictably effective for each patient be developed and standardized. We term this domain precision medicine.

… disruption-enabling diagnostic technologies long ago shifted the care of most infectious diseases from intuitive medicine (when diseases were given labels such as “consumption”) to the realm of precision medicine (where they can be defined as precisely as different types of infection, different categories of lung disease, and so on). To the extent that we know what type of bacterium, virus, or parasite causes one of these diseases—and when we know the mechanism by which the infection propagates—predictably effective therapies can be developed—therapies that address the cause, not just the symptom. As a result, nurses can now provide care for many infectious diseases, and patients with these diseases rarely require hospitalization. Diagnostics technologies are enabling similar transformations, disease by disease, for families of much more complicated conditions that historically have been lumped into categories we have called cancer, hypertension, Type II diabetes, asthma, and so on.

When I was a kid, we talked about “curing cancer” as the prototypical world-shaking accomplishment. The reason there is no one “cure for cancer” is that cancer is not one disease but hundreds of different diseases involving different genes going awry in the direction of too much growth. A cure needs to be found for each one of those diseases in order for there to be a cure for the amorphous notion of “cancer.” Many of these diseases have been cured and others are well on their way to being cured. But other diseases under the general heading of “cancer” have not even been identified yet (in the sense of carefully distinguishing them from other diseases with similar symptoms). Once they have been identified at the level of the particular gene that goes awry to produce that particular disease, they will be halfway to being cured.

The term “personalized medicine” is sometimes used for what I would call “treating the disease someone actually has instead of some other disease.” A better phrase for that is the phrase Clay, Jerome and Jason use: “precision medicine.”

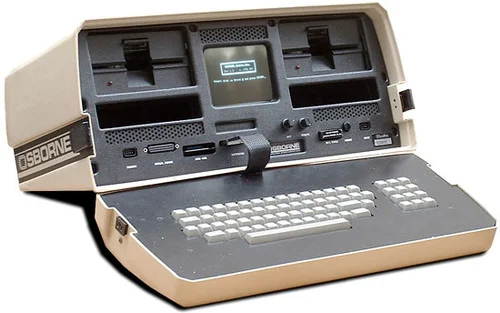

Clay Christensen, Jerome Grossman and Jason Hwang on the Personal Computer Revolution

I saw the personal computer revolution firsthand. It all went down very fast. In December 1973, when I was 13, I got a chance to use a calculator for the first time. I was visiting my brother Christian Kimball (1, 2), who was then an undergraduate at Harvard; there was a calculator in one of the Harvard libraries that allowed me to do conversions between 3-dimensional radial coordinates of nearby stars to xyz coordinates so I could better understand the layout of our interstellar neighborhood. A year and half later, in 1975, I learned a little computer programming at an NSF supported math camp at Utah State University. In 1978 and 1979 I had to get special access to Harvard Business School computers in order to run some regressions. But in August 1983, I convinced my father (1, 2) to help me buy a used Osborne “portable” computer. It wasn’t easy to learn to use, but I did ultimately write my Harvard Ph.D. program economic history paper “Farmer’s Cooperatives as Behavior Towards Risk” (which was ultimately published in the American Economic Review). In 1986 and 1987, when I wrote my dissertation, I was only able to manage to typeset all of the equations because my wife Gail was an ace scientific secretary with access to the needed computers and software. (After I convinced her to marry me and move to Massachusetts, she found a job working as a secretary first for professors at Harvard Business School and then later for Eric Maskin, Mike Whinston in the Economics Department.) But by Fall of 1987, as a new assistant professor at the University of Michigan, I could typeset equations myself using TeX (not yet LaTeX) on the new desktop computer the University of Michigan had given me.

In The Innovator’s Prescription (location 316), Clay Christensen, Jerome Grossman and Jason Hwang give this analytical account of the personal computer revolution:

Until the 1970s there were only a few thousand engineers in the world who possessed the expertise required to design mainframe computers, and it took deep expertise to operate them. The business model required to make and market these machines required gross profit margins of 60 percent just to cover the inherent overhead. The personal computer disrupted this industry by making computing so affordable and accessible that hundreds of millions of people could own and use computers.

The technological enabler of this disruption was the microprocessor, which so simplified the problems of computer design and assembly that Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs could slap together an Apple computer in a garage. And Michael Dell could build them in his dorm room.

However, by itself, the microprocessor was not sufficient. IBM and Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) both had this technological enabler inside their companies, for example. DEC eschewed business model innovation and tried instead to commercialize the personal computer from within its minicomputer business model, a model that simply could not make money if computers were priced below $50,000. IBM, in contrast, set up an innovative business model in Florida, far from its mainframe and minicomputer business units in New York and Minnesota. In its PC business model, IBM could make money with low margins, low overhead costs, and high unit volumes. By coupling the technological and business model enablers, IBM transformed the computing industry and much of the world with it, while DEC was swept away.

And it wasn’t just the makers of expensive computers that were swept away. The systems of component and software suppliers, and the sales and service channels that had sustained the mainframe and minicomputer industries, were all disrupted by a new supporting cast of companies whose economics, technologies, and competitive rhythms matched those of the personal computer makers. An entire new value network displaced the old network.

The analogy Clay, Jerome and Jason draw to health care is that one need not despair when seeing how the bulk of health care providers are set up to do things in a very expensive way. As long as we don’t let regulations smother new providers, doing things in new, less expensive ways–though perhaps at first in somewhat lower quality ways–there is hope. (See “Clay Christensen, Jerome Grossman and Jason Hwang on the Agenda for the Transformation of Health Care” and “Tyler Cowen: Regulations Hinder Development of Driverless Cars.”)

Clay Christensen, Jerome Grossman and Jason Hwang on How the History of Other Industries Gives Hope for Health Care

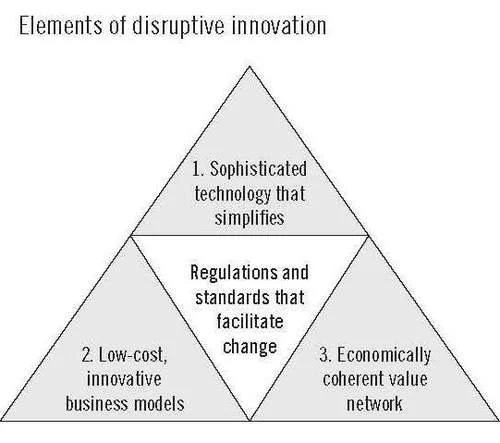

Image from The Innovator’s Prescription, location 294

Things start hard and then get easier. This can be true even for health care. Here are the examples that Clay Christensen, Jerome Grossman and Jason Hwang give in The Innovator’s Prescription:

The problems facing the health-care industry actually aren’t unique. The products and services offered in nearly every industry, at their outset, are so complicated and expensive that only people with a lot of money can afford them, and only people with a lot of expertise can provide or use them. Only the wealthy had access to telephones, photography, air travel, and automobiles in the first decades of those industries. Only the rich could own diversified portfolios of stocks and bonds, and paid handsome fees to professionals who had the expertise to buy and sell those securities. Quality higher education was limited to the wealthy who could pay for it and the elite professors who could provide it. And more recently, mainframe computers were so expensive and complicated that only the largest corporations and universities could own them, and only highly trained experts could operate them. (We will come back to this last example, below.)

It’s the same with health care. Today, it’s very expensive to receive care from highly trained professionals. Without the largesse of well-heeled employers and governments that are willing to pay for much of it, most health care would be inaccessible to most of us.

At some point, however, these industries were transformed, making their products and services so much more affordable and accessible that a much larger population of people could purchase them, and people with less training could competently provide them and use them. We have termed this agent of transformation disruptive innovation. It consists of three elements (shown in Figure I.1). Technological enabler. Typically, sophisticated technology whose purpose is to simplify, it routinizes the solution to problems that previously required unstructured processes of intuitive experimentation to resolve. Business model innovation. Can profitably deliver these simplified solutions to customers in ways that make them affordable and conveniently accessible. Value network. A commercial infrastructure whose constituent companies have consistently disruptive, mutually reinforcing economic models.

Using some terminology Clay Christensen uses in all of his books, the key problem with health care is that so much of it is set up on the “solution shop” business model. The “solution shop” business model is familiar to academics in research universities because the kind of research done in academic is almost always done in a solution-shop way, by specialized crafting of ways to get a scientific job done. The only way to make health care significantly cheaper is to routinize and “deskill” or at least “downskill” much of it so that the job for at least the easy cases can be done in a way that is more in the spirit of mass-production: as a “value-added process.”

Clay Christensen, Jerome Grossman and Jason Hwang on the Agenda for the Transformation of Health Care

As I said in my post “Saint Clay," I plan to feature the work of Clay Christensen and his coauthors in a slow, thoroughgoing, methodical way, much as I have featured John Stuart Mill's On Liberty. Because of its urgency in the policy debate, I will start with Clay Christensen, Jerome Grossman and Jason Hwang’s book, "The Innovator’s Prescription.” Here is how they lay out their agenda in the introduction to the book:

The growth in health-care spending in the United States regularly outpaces the growth of the overall economy. Over the last 35 years, while the nation’s spending on all goods and services has risen at an average annual rate of 7.2 percent, the amount spent on health care has grown at a rate of 9.8 percent.1 As a consequence, an increasing proportion of Americans simply cannot afford adequate care. Many efforts to contain overall costs have the effect of making care inaccessible on a convenient and timely basis for all of us—even for those who can pay for it.

Second, if federal government spending remains a relatively constant percentage of GDP, the rising cost of Medicare within that budget will crowd out all other spending except defense within 20 years.

The third factor that engenders fear is that the burden of covering the costs of health care for employees, retirees, and their families is forcing some of America’s most economically important companies to become uncompetitive in world markets. Health-care costs add over $1,500 to the cost of every car our automakers sell, for example.

The fourth frightening factor, about which few people are aware, is that if governments were forced to report on their financial statements the liabilities they face resulting from contractual commitments to provide health care for retired employees, nearly every city and town in the United States would be bankrupt. There is no way for them to pay for what they are obligated to pay, except by denying funding for schools, roads, and public safety, or by raising taxes to extreme levels.

What can be done? It isn’t easy:

Those fighting for reform have few weapons for systemic change. Most can only work on improving the cost and efficacy of their piece of the system. There are very few system architects among these forces that have the scope and power of a commanding general to reconfigure the elements of the system.

Perhaps most discouraging of all, however, is that there is no credible map of the terrain ahead that reformers agree upon and trust. They are armed with data about the past, and they have become accustomed to reaching consensus for action when the data are conclusive. But because there are no data about the future, there is no map available to convincingly show these reformers which of the pathways ahead of them lead to a dead end and which constitute a promising road to reform. And few have a sense for the interconnectedness of these pathways. As the prophet of Proverbs said, “Where there is no vision, the people perish.”

So why this book? There is little dispute that we need a system that is competitive, responsive, and consumer-driven, with clear metrics of value per dollar being spent.9 Our hope is that The Innovator’s Prescription can provide a road map for those seeking innovation and reform—an accurate description of the terrain ahead, about which data are not yet available. Much of today’s political dialogue on health-care reform centers on how to pay for the cost of health care in the future. This book offers the other half of the equation: how to innovate to reduce costs and improve the quality and accessibility of care. We don’t simply ask how we can afford health care. We show how to make it affordable—less costly and of better quality.

To preview the main message, the number one policy in order to foster progress in most any area is to make sure that new entrants, who may initially do things worse in some dimensions, but more cheaply or more conveniently than the established incumbents, have a chance to gain a foothold in the market. Then what the new entrants do has a chance to improve in quality until in the end they bring down prices even at high quality, just as personal computers, which initially were not very good, became more powerful–as well as less expensive and more convenient–than the mainframes of old (only to be challenged in turn by smartphones and tablets).

One possible reaction to this would be to object to the idea of having anyone get medical care that is cheaper and more convenient, but is otherwise of somewhat worse quality. But the result of acting as if cost does not matter is the startling fact discussed in "Another Quality Control Failure on the Wall Street Journal Editorial Page?“ that real after-tax, after-transfer income for the poorest 20% of the population has increased by 49% since 1979. As the title of my post suggests, I thought this was a mistake. But it is not. What the Congressional Budget Office did to come up with this number was to count as part of after-tax, after-transfer income the full cost of both medical care paid for by employers and medical care paid for by the government (much of it through Medicaid). If you don’t feel that the poorest 20% of the population is as much better off since 1979 as a 49% increase in income would suggest, it is an indication that all of that money spent on medical care has not gotten the value that one would think it should have been able to purchase.

Our current medical system has too few good paths for finding ways to do things more cheaply and conveniently. If we block all paths that lead even temporarily through a region of lower cost at lower quality and greater convenience, the next 35 years may see another 49% increase in the after-tax, after-transfer income of the bottom 20% of the population that hardly feels like an improvement in living standards at all, as we head toward more and more expensive medicine that is only marginally better in quality. Alternatively, we can allow disruptive innovation that will get much better quality, much lower cost and much greater convenience 35 years from now if we avoid crushing in their infancy ways of doing things that right now are much cheaper and more convenient, but slightly lower in other dimensions of quality.

Right now, many people would gladly choose lower expense and greater convenience for some types of medical care even at slightly lower quality in other dimensions, if they were allowed (by any of half of dozen different possible mechanisms) to get a true signal about the actual tradeoffs that society faces in this regard. Too often, discussion about these tradeoffs only points out the static welfare gains from helping people to incorporate the cost of various types of health care into their decisions. I am persuaded by Clay, Jerome and Jason’s arguments that the dynamic gains are much more important.

Quartz #45—>Actually, There Was Some Real Policy in Obama's Speech

Here is the full text of my 45th Quartz column, “Actually, there was some real policy in Obama’s speech,” now brought home to supplysideliberal.com. It was first published on January 29, 2014. Links to all my other columns can be found here.

If you want to mirror the content of this post on another site, that is possible for a limited time if you read the legal notice at this link and include both a link to the original Quartz column and the following copyright notice:

© January 29, 2014: Miles Kimball, as first published on Quartz. Used by permission according to a temporary nonexclusive license expiring June 30, 2015. All rights reserved.

In National Review Online, Ramesh Ponnuru described last night’s State of the Union speech as “… a laundry list of mostly dinky initiatives, and as such a return to Clinton’s style of State of the Union addresses.” I agree with the comparison to Bill Clinton’s appeal to the country’s political center, but Ponnuru’s dismissal of the new initiatives the president mentioned as “dinky” is short-sighted.

In the storm and fury of the political gridiron, the thing to watch is where the line of scrimmage is. And it is precisely initiatives that seem “dinky” because they might have bipartisan support that best show where the political and policy consensus is moving. Here are the hints I gleaned from the text of the State of the Union that policy and politics might be moving in a helpful direction.

- The president invoked Michelle Obama’s campaign against childhood obesity as something uncontroversial. But this is actually part of what could be a big shift toward viewing obesity to an important degree as a social problem to be addressed as communities instead of solely as a personal problem.

- The president pushed greater funding for basic research, saying: “Congress should undo the damage done by last year’s cuts to basic research so we can unleash the next great American discovery.” Although neither party has ever been against support for basic research, budget pressures often get in the way. And limits on the length of State of the Union addresses very often mean that science only gets mentioned when it touches on political bones of contention such as stem-cell research or global warming. So it matters that support for basic research got this level of prominence in the State of the Union address. In the long run, more funding for the basic research could have a much greater effect on economic growth than most of the other economicpolicies debated in Congress.

- The president had kind words for natural gas and among “renewables” only mentions solar energy. This marks a shift toward a vision of coping with global warming that can actually work: Noah Smith’s vision of using natural gas while we phase out coal and improving solar power until solar power finally replaces most natural gas use as well. It is wishful thinking to think that other forms of renewable energy such as wind power will ever take care of a much bigger share of our energy needs than they do now, but solar power is a different matter entirely. Ramez Naam’s Scientific American blog post “Smaller, cheaper, faster: Does Moore’s law apply to solar cells“ says it all. (Don’t miss his most striking graph, the sixth one in the post.)

- The president emphasized the economic benefits of immigration. I wish he would go even further, as I urged immediately after his reelection in my column, “Obama could really help the US economy by pushing for more legal immigration.” The key thing is to emphasize increasing legal immigration, in a way designed to maximally help our economy. If the rate of legal immigration is raised enough, then the issue of “amnesty” for undocumented immigrants doesn’t have to be raised: if the line is moving fast enough, it is more reasonable to ask those here against our laws to go to the back of the line. The other way to help politically detoxify many immigration issues is to reduce the short-run partisan impact of more legal immigration by agreeing that while it will be much easier to become a permanent legal resident,citizenship with its attendant voting rights and consequent responsibility to help steer our nation in the right direction is something that comes after many years of living in America and absorbing American values. Indeed, I think it would be perfectly reasonable to stipulate that it should take 18 years after getting a green card before becoming a citizen and getting the right to vote—just as it takes 18 years after being born in America to have the right to vote.

- With his push for pre-kindergarten education at one end and expanded access to community colleges at the other end, Obama has recognized that we need to increase the quantity as well as the quality of education in America. This is all well and good, but these initiatives are focusing on the most costly ways of increasing the quantity of education. The truly cost-effective way of delivering more education is to expand the school day and school year. (I lay out how to do this within existing school budgets in “Magic Ingredient 1: More K-12 School.”)

- Finally, the president promises to create new forms of retirement savings accounts (the one idea that Ramesh Ponnuru thought was promising in the State of the Union speech). Though this specific initiative is only a baby step, the idea that we should work toward making it easier from a paperwork point of view for people to start saving for retirement than to not start saving for retirement is an idea whose time has come. And it is much more important than people realize. In a way that takes some serious economic theory to explain, increasing the saving rate by making it administratively easier to start saving effects not only people’s financial security during retirement, but also aids American competitiveness internationally, by making it possible to invest out of American saving instead of having to invest out of China’s saving.

Put together, the things that Barack Obama thought were relatively uncontroversial to propose in his State of the Union speech give me hope that key aspects of US economic policy might be moving in a positive direction, even while other aspects of economic policy stay sadly mired in partisan brawls. I am an optimist about our nation’s future because I believe that, in fits and starts, good ideas that are not too strongly identified with one party or the other tend to make their way into policy eventually. Political combat is noisy, while political cooperation is quiet. But quiet progress counts for a lot. And glimmers of hope are better than having no hope at all.

John Cochrane: What Free-Market Medical Care Would Look Like

I love John Cochrane’s health care proposal in the December 26, 2013 Wall Street Journal op-ed “What to Do When Obamacare Unravels” (ungated on John’s blog). It should work very well, and to the extent it is imperfect, experimenting with John Cochrane’s proposal would teach us a lot more about health care delivery than the Obamacare experiment will.

My favorite passage is this:

No other country has a free health market, you may object. The rest of the world is closer to single payer, and spends less.

Sure. We can have a single government-run airline too. We can ban FedEx and UPS, and have a single-payer post office. We can have government-run telephones and TV. Thirty years ago every other country had all of these, and worthies said that markets couldn’t work for travel, package delivery, the “natural monopoly” of telephones and TV. Until we tried it. That the rest of the world spends less just shows how dysfunctional our current system is, not how a free market would work.

I wish I had written “What to Do When Obamacare Unravels.” I have some hopes that what I did write, “Don’t Believe Anyone Who Claims to Understand the Economics of Obamacare,” is still worth reading as a companion article to what John says.

Update: There is a very interesting discussion of this post on my Facebook wall.

Quartz #33—>Don't Believe Anyone Who Claims to Understand the Economics of Obamacare

Here is the full text of my 33d Quartz column “Don’t believe anyone who claims to understand the economics of Obamacare,“ now brought home to supplysideliberal.com. It was first published on October 3, 2013. Links to all my other columns can be found here.

If you want to mirror the content of this post on another site, that is possible for a limited time if you read the legal notice at this link and include both a link to the original Quartz column and the following copyright notice:

© October 3, 2013: Miles Kimball, as first published on Quartz. Used by permission according to a temporary nonexclusive license expiring June 30, 2015. All rights reserved.

Below, after the text of the column as it appeared in Quartz, I have the original introduction, and some reactions to the column.

Republican hatred of Obamacare and Democratic support for Obamacare have shut down the US government. Now might be a good time to remind the world just how far the country’s health care sector—with or without Obamacare—is from being the kind of classical free market Adam Smith was describing when he talked about the beneficent “invisible hand” of the free market. There are at least five big departures of our health care system from a classical free market:

1. Health care is complex, and its outcomes often cannot be seen until years later, when many other confounding forces have intervened. So the assumption that people are typically well informed—or as well informed as their health care providers—is sadly false. (And the difficulties that juries have in understanding medicine create opportunities for lawyers to get large judgments for plaintiffs in malpractice suits.)

2. Even aside from the desire to cure contagious diseases before they spread, people care not only about their own health and the health of their families, but also the health of strangers. On average, it makes people feel worse to see others suffering from sickness than to see others suffering from aspects of poverty unrelated to sickness.

3. “Scope of practice” laws put severe restrictions on what health care workers can do. For example, there are many routine things that nurses could do just as well as a general practitioner, but are not allowed to do because they are not doctors–and the paths to becoming a “medical doctor” are strictly controlled.

4. Those who have insurance pay only a small fraction of the cost of the medical procedures they get, leading them to agree to many expensive medical procedures even in cases where the benefit is likely to be small.

5. In order to spur research into new drugs, the government gives temporary monopolies on the production of life-saving drugs—a.k.a. patents—that push the price of those drugs far above the actual cost of production.

Sometimes these departures from a classical free market cancel each other out, as when insurance firms shield patients from the official price of a drug and make the cost of that drug to the patient close to the social cost of producing it, or when laws prevent outright quacks from performing brain surgery on an ill-informed patient. But one way or another, there is no obvious “free market” anywhere in sight. That doesn’t mean that the economic reasoning behind the virtues of the free market doesn’t help, it just means that when we think about health care policy, we swim in deep water.

At the level of overall health care systems, one of the most important things we know is that many other countries seem to get reasonably good health care outcomes while spending much less money than we do in the US. There are several factors that might contribute to relatively good health results in other countries:

- There are large gains in health from making sure that everyone in society gets very basic medical care on a basis more regular than emergency room visits.

- Most other countries have less of a devotion to fast food—and food from grocery store shelves that is processed to taste as good as possible (in the sense of “can’t eat just one”) without regard to overall actual (as opposed to advertising-driven) health properties.

- Most other countries are either poor enough, or rely enough on public transportation, that people are forced to walk or ride bicycles significant distances to get to where they need to go every day.

Part of the recipe for spending less in other countries is the fact that they can cheaply copy drugs and medical techniques developed in the US at great expense, But, there are two simple ingredients to the recipe beyond that:

- Ration procedures that don’t seem very effective (inevitably along with some inappropriate rationing as well)

- Use the fact that most of the money for health care runs through the government as leverage to push down the pay of doctors and other health care workers.

My main concern about Obamacare is the fear that it will inhibit experimentation with different ways of organizing health care at the state level. So far that is only a fear, but it is something to watch for. But there is one way in which state-level approaches are severely limited: they can’t push down the pay of doctors and other health care workers without causing an exodus of doctors and other health care workers to other states. National health care reform can be more powerful than state-level health care reform if a key aim, stated or not, is to reduce the pay of doctors and other health care workers (and workers in closely connected fields, such as those who work in insurance companies) in order to make medical care cheaper for everyone else. Fewer stars would go into medicine if it paid less—but if most of the benefits from health care are from basic care, that might not show up too much in the overall health statistics. And if less-expensive nurses can do things that expensive doctors are now doing, those who would have been nurses will still do a good job if they end up becoming doctors because the pay is too low for the stars to fill the medical school slots.

Reducing the total amount of money flowing through the health care sector should reduce both the amount of health care and the price of health care. But even in a best-case scenario, in which reasonably judicious approaches to rationing and dramatic advances in persuading people to exercise and eat right kept the overall health statistics looking good, a reduction in the price and quantity of health care could mean a big reduction in income for those working in health care and related fields.

Still, the key wild card in judging Obamacare will be its effect on health care innovation. Subsidies may get people more care now, but crowd out government funding for basic medical research. Efforts to standardize medical care could easily yield big gains at the start as hospitals come up to best practice, yet that standardization could make innovation harder later on. An emphasis on cost-containment could encourage cost-reducing innovations, but discourage the development of new treatments that are very expensive at first, but could become cheaper later on. And Obamacare will tend to substitute the judgments of other types of health care experts in place of the judgments of business people, with unknown effects. Whatever the effects of Obamacare on innovation, we can be confident that over time these effects on innovation will dwarf most of the other effects of Obamacare in importance.

The October 2013 US government shutdown is only the latest of many twists and turns in the bitter struggle over Obamacare. A large share of the partisan energy comes from people who feel certain they know what Obamacare will do. But ideology makes things seem obvious that are not obvious at all. The social science research I have seen on health care regularly turns up surprises. To me, the most surprising thing would be if what Obamacare actually does to health care in America didn’t surprise us many times over, both pleasantly and unpleasantly, at the same time.

Here is my original introduction, which was drastically trimmed down for the version on Quartz:

Republican hatred of Obamacare, and Democratic support for Obamacare, have shut down the “non-essential” activities of the Federal Government. So, three-and-a-half years since President Obama signed the “Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act” into law, and a year or so since a presidential election in which Obamacare was a major issue, it is a good time to think about Obamacare again.

In my first blog post about health care, back in June 2012, I wrote:

I am slow to post about health care because I don’t know the answers. But then I don’t think anyone knows the answers. There are many excellent ideas for trying to improve health care, but we just don’t know how different changes will work in practice at the level of entire health care systems.That remains true, but thanks to the intervening year, I have high hopes that with some effort, we can be, as the saying goes, “confused on a higher level and about more important things.”

One thing that has come home to me in the past year is just how far the US health care sector—with or without Obamacare—is from being the kind of classical free market Adam Smith was describing when he talked about the beneficent “invisible hand” of the free market.

Reactions: Gerald Seib and David Wessel Included this column in their “What We’re Reading” Feature in the Wall Street Journal. Here is their excellent summary:

The key to the long-run impact of Obamacare will be whether it smothers innovation in health care — both in the way it is organized and in the development of new treatments. And no one today can know whether that’ll happen, says economist Miles Kimball. [Quartz]

(In response, Noah Smith had this to say about me and the Wall Street Journal.) This column was also featured in Walter Russell Mead’s post "How Will We Know If Obamacare Succeeds or Fails.” (Thanks to Robert Graboyes for pointing me to that post.) He writes:

Meanwhile, at Quartz, Miles Kimball has a post entitled “Don’t Believe Anyone Who Claims to Understand the Economics of Obamacare.” The whole post is worth reading, but near the end, he argues that the ACA’s effect on innovation could eventually be the most important thing about it’s long-term legacy…

From our perspective, these are both very good places to start thinking about how to measure Obamacare’s impact. Of course, Tozzi’s metric is easier to quantify than Kimball’s: it will be difficult to judge how the ACA is or isn’t limiting innovation. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try: without innovation, there’s no hope for a sustainable solution to the ongoing crisis of exploding health care costs.

I have also been pleased by some favorable tweets. Here is a sampling:

- Matthew Yglesias: “Solid @MilesKimball column on the very uncertain long-term impact of Obamacare”

- Adam Gurri: “Great piece by @mileskimball on the nuances of figuring out what Obamacare even does”

- Ramez Naam: “Thought provoking piece by @mileskimball on how little we understand health care economics, & how key innovation is.”

- Philip Walach: “Epistemological modesty is in much too short supply.@mileskimball has refreshingly honest take on ACA: nobody knows.”

Don't Believe Anyone Who Claims to Understand the Economics of Obamacare

Here is my original introduction, which was drastically trimmed down for the version on Quartz:

Republican hatred of Obamacare, and Democratic support for Obamacare, have shut down the “non-essential” activities of the Federal Government. So, three-and-a-half years since President Obama signed the “Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act” into law, and a year or so since a presidential election in which Obamacare was a major issue, it is a good time to think about Obamacare again.

In my first blog post about health care, back in June 2012, I wrote:

I am slow to post about health care because I don’t know the answers. But then I don’t think anyone knows the answers. There are many excellent ideas for trying to improve health care, but we just don’t know how different changes will work in practice at the level of entire health care systems.That remains true, but thanks to the intervening year, I have high hopes that with some effort, we can be, as the saying goes, “confused on a higher level and about more important things.”

One thing that has come home to me in the past year is just how far the US health care sector—with or without Obamacare—is from being the kind of classical free market Adam Smith was describing when he talked about the beneficent “invisible hand” of the free market.

Reactions: Gerald Seib and David Wessel Included this column in their “What We’re Reading” Feature in the Wall Street Journal. Here is their excellent summary:

The key to the long-run impact of Obamacare will be whether it smothers innovation in health care – both in the way it is organized and in the development of new treatments. And no one today can know whether that’ll happen, says economist Miles Kimball. [Quartz]

(In response, Noah Smith had this to say about me and the Wall Street Journal.) This column was also featured in Walter Russell Mead’s post “How Will We Know If Obamacare Succeeds or Fails.” (Thanks to Robert Graboyes for pointing me to that post.) He writes:

Meanwhile, at Quartz, Miles Kimball has a post entitled “Don’t Believe Anyone Who Claims to Understand the Economics of Obamacare.” The whole post is worth reading, but near the end, he argues that the ACA’s effect on innovation could eventually be the most important thing about it’s long-term legacy…

From our perspective, these are both very good places to start thinking about how to measure Obamacare’s impact. Of course, Tozzi’s metric is easier to quantify than Kimball’s: it will be difficult to judge how the ACA is or isn’t limiting innovation. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try: without innovation, there’s no hope for a sustainable solution to the ongoing crisis of exploding health care costs.

I have also been pleased by some favorable tweets. Here is a sampling:

- Matthew Yglesias: “Solid @MilesKimball column on the very uncertain long-term impact of Obamacare”

- Adam Gurri: “Great piece by @mileskimball on the nuances of figuring out what Obamacare even does”

- Ramez Naam: “Thought provoking piece by @mileskimball on how little we understand health care economics, & how key innovation is.”

- Philip Walach: “Epistemological modesty is in much too short supply. @mileskimball has refreshingly honest take on ACA: nobody knows.”

Clay Christensen, Jeffrey Flier and Vineeta Vijayaraghavan on How to Make Health Care More Cost Effective

Clay Christensen, Jeffrey Flier and Vineeta Vijaraghavan argue in their Wall Street Journal op-ed “The Coming Failure of Accountable Care” a few days ago that Obamacare’s “accountable care organizations” will have trouble changing doctors’ behavior in the dramatic ways envisioned. They will have even more trouble changing patients’ behavior, since accountable care organizations provide few incentives for patients to change their behavior.

In the debates over health care reform, advocates of Obamacare have made a great deal of the lower per-patient costs of medical care in other advanced countries. Those lower per-patient costs of medical care in other advanced countries have a lot to do with lower pay for doctors and other medical-care providers. If something on the Obamacare model succeeds in lowering medical costs significantly, I suspect it will be because it forces down doctors’ pay, as government budget constraints lead to tighter and tighter price controls.

Clay, Jeffrey and Vineeta’s list of recommendations would instead use market liberalization to lower the amount paid for medical services. Here is their prescription:

• Consider opportunities to shift more care to less-expensive venues, including, for example, “Minute Clinics” where nurse practitioners can deliver excellent care and do limited prescribing. New technology has made sophisticated care possible at various sites other than acute-care, high-overhead hospitals.

• Consider regulatory and payment changes that will enable doctors and all medical providers to do everything that their license allows them to do, rather than passing on patients to more highly trained and expensive specialists.

• Going beyond current licensing, consider changing many anticompetitive regulations and licensure statutes that practitioners have used to protect their guilds. An example can be found in states like California that have revised statutes to enable highly trained nurses to substitute for anesthesiologists to administer anesthesia for some types of procedures.

• Make fuller use of technology to enable more scalable and customized ways to manage patient populations. These include home care with patient self-monitoring of blood pressure and other indexes, and far more widespread use of “telehealth,” where, for example, photos of a skin condition could be uploaded to a physician. Some leading U.S. hospitals have created such outreach tools that let them deliver care to Europe. Yet they can’t offer this same benefit in adjacent states because of U.S. regulation.

Free market advocates have been calling for such approaches for some time. Doctors have understandably lobbied for a continuation of market restrictions that boost their pay. Now that doctors face reduced pay under budget pressures created by Obamacare as well, such market liberalization in medical care may begin to seem like the lesser of two evils for doctors. And it could be a great boon to the rest of us.

For the record, here is my position on health care reform, quoted from my post “Evan Soltas on Medical Reform Federalism–in Canada”:

Let’s abolish the tax exemption for employer-provided health insurance, with all of the money that would have been spent on this tax exemption going instead to block grants for each state to use for its own plan to provide universal access to medical care for its residents.

This recommendation is based on what I said in my first post about health care, “Health Economics”:

I am slow to post about health care because I don’t know the answers. But then I don’t think anyone knows the answers. There are many excellent ideas for trying to improve health care, but we just don’t know how different changes will work in practice at the level of entire health care systems.

The more the Washington encourages a diversity of approaches to health care, the more we will learn about what works. On the other hand, the more Washington does to force health care policy into the same mold in each state, the more likely it is that we will only learn one thing at the systems-level: that the first try in the one-size-fits-all approach doesn’t work very well.

God and Devil in the Marketplace

Jonathan Haidt, in The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion, pp. 303, 304:

The next time you go to the supermarket, look closely at a can of peas. Think about all the work that went into it–the farmers, truckers, and supermarket employees, the miners and metalworkers who made the can–and think how miraculous it is that you can buy this can for under a dollar. At every step of the way, competition among suppliers rewarded those whose innovations shaved a penny off the cost of getting that can to you. If God is commonly thought to have created the world and then arranged it for our benefit, then the free market (and its invisible hand) is a pretty good candidate for being a god. You can begin to understand why libertarians sometimes have a quasi-religious faith in free markets.

Now let’s do the devil’s work and spread chaos throughout the marketplace. Suppose that one day all prices are removed from all products in the supermarket. All labels too, beyond a simple description of the contents, so you can’t compare products from different companies. You just take whatever you want, as much as you want, and bring it up to the register. The checkout clerk scans in your food insurance card and helps you fill out your itemized claim. You pay a flat fee of $10 and go home with your groceries. A month later you get a bill informing you that your food insurance company will pay the supermarket for most of the remaining cost, but you’ll have to send in a check for an additional $15. It might sound like a bargain to get a cartload of food for $25, but you’re really paying your grocery bill every month when you fork over $2000 for your food insurance premium.

Under such a system, there is little incentive for anyone to find innovative ways to reduce the cost of food or increase its quality. The supermarkets get paid by the insurers, and the insurers get their premiums from you. The cost of food insurance begins to rise as supermarkets stock only the foods that net them the highest insurance payments, not the foods that deliver value to you.

As the cost of food insurance rises, many people can no longer afford it. Liberals (motivated by Care) push for a new government program to buy food insurance for the poor and the elderly. But once the government becomes the major purchaser of food, then success in the supermarket and food insurance industries depends primarily on maximizing yield from government payouts. Before you know it, that can of peas costs the government $30, and all of us are paying 25% of our paychecks in taxes just to cover the cost of buying groceries for each other at hugely inflated costs.

In 2009, [David] Goldhill published a provocative essay in the Atlantic titled “How American Health Care Killed My Father”: One of his main points was the absurdity of using insurance to pay for routine purchases. Normally we buy insurance to cover the risk of a catastrophic loss. We enter an insurance pool with other people to spread the risk around, and we hope never to collect a penny. We handle routine expenses ourselves, seeking out the highest quality for the lowest price. We would never file a claim on our car insurance to pay for an oil change.