Clay Christensen, Jerome Grossman and Jason Hwang on How the History of Other Industries Gives Hope for Health Care

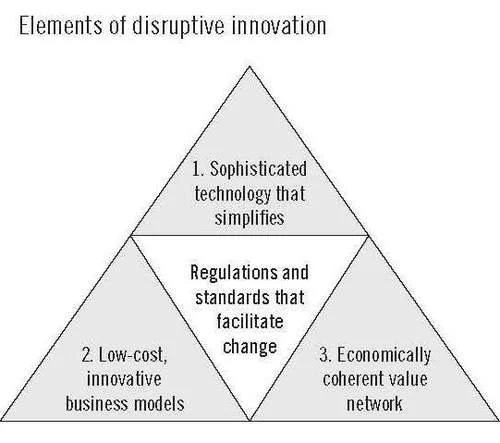

Image from The Innovator’s Prescription, location 294

Things start hard and then get easier. This can be true even for health care. Here are the examples that Clay Christensen, Jerome Grossman and Jason Hwang give in The Innovator’s Prescription:

The problems facing the health-care industry actually aren’t unique. The products and services offered in nearly every industry, at their outset, are so complicated and expensive that only people with a lot of money can afford them, and only people with a lot of expertise can provide or use them. Only the wealthy had access to telephones, photography, air travel, and automobiles in the first decades of those industries. Only the rich could own diversified portfolios of stocks and bonds, and paid handsome fees to professionals who had the expertise to buy and sell those securities. Quality higher education was limited to the wealthy who could pay for it and the elite professors who could provide it. And more recently, mainframe computers were so expensive and complicated that only the largest corporations and universities could own them, and only highly trained experts could operate them. (We will come back to this last example, below.)

It’s the same with health care. Today, it’s very expensive to receive care from highly trained professionals. Without the largesse of well-heeled employers and governments that are willing to pay for much of it, most health care would be inaccessible to most of us.

At some point, however, these industries were transformed, making their products and services so much more affordable and accessible that a much larger population of people could purchase them, and people with less training could competently provide them and use them. We have termed this agent of transformation disruptive innovation. It consists of three elements (shown in Figure I.1). Technological enabler. Typically, sophisticated technology whose purpose is to simplify, it routinizes the solution to problems that previously required unstructured processes of intuitive experimentation to resolve. Business model innovation. Can profitably deliver these simplified solutions to customers in ways that make them affordable and conveniently accessible. Value network. A commercial infrastructure whose constituent companies have consistently disruptive, mutually reinforcing economic models.

Using some terminology Clay Christensen uses in all of his books, the key problem with health care is that so much of it is set up on the “solution shop” business model. The “solution shop” business model is familiar to academics in research universities because the kind of research done in academic is almost always done in a solution-shop way, by specialized crafting of ways to get a scientific job done. The only way to make health care significantly cheaper is to routinize and “deskill” or at least “downskill” much of it so that the job for at least the easy cases can be done in a way that is more in the spirit of mass-production: as a “value-added process.”