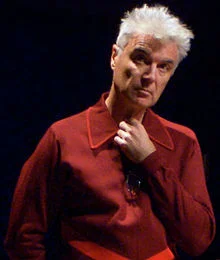

David Byrne on Non-Monetary Motivations

As illustrated by arguments I make in my posts “Scott Adams’s Finest Hour: How to Tax the Rich” and “Copyright,” understanding the strength of non-monetary motivations for work is important for public policy. David Byrne gives a vivid description of non-monetary motivations in his line of work in this passage from his book How Music Works, pp. 203-204.

How important is getting one’s work out to the public? Should that even matter to a creative artist? Would I make music if no one were listening? If I were a hermit and lived on a mountaintop like a bearded guy in a cartoon, would I take the time to write a song? Many visual artists whose work I love–like Henry Darger, Gordon Carter, and James Castle–never shared their art. They worked ceaselessly and hoarded their creations, which were discovered only after they died or moved out of their apartments. Could I do that? Why would I? Don’t we want some validation, respect, feedback? Come to think of it, I might do it–in fact, I did, when I was in high school puttering around with those tape loops and splicing. I think those experiments were witnessed by exactly one friend. However, even an audience of one is not zero.

Still, making music is its own reward. It feels good and can be a therapeutic outlet; maybe that’s why so many people work hard in music for no money or public recognition at all. In Ireland and elsewhere, amateurs play well-known songs in pubs, and their ambition doesn’t stretch beyond the door. They are getting recognition (or humiliation) within their village, though.

In North America, families used to gather around the piano in the parlor. Any monetary remuneration that might have accrued from these “concerts” was secondary. To be honest, even tooling around with tapes in high school, I think I imagined that someone, somehow, might hear my music one day. Maybe not those particular experiments, but I imagined that they might be the baby steps that would allow my more mature expressions to come into being and eventually reach others. Could I have unconsciously had such a long-range plan? I have continued to make plenty of music, often with no clear goal in sight, but I guess somewhere in the back of my mind I believe that the aimless wandering down a meandering path will surely lead to some (well-deserved, in my mind) reward down the road. There’s a kind of unjustified faith involved here.

Is the satisfaction that comes from public recognition–however small, however fleeting–a driving force for the creative act? I am going to assume that most of us who make music (or pursue other create endeavors) do indeed dream that someday someone else will hear, see, or read what we’ve made.

For balance, I should point out that in the paragraph after this passage, David writes of monetary motivations as well:

Many of us who do seek validation dream that we will not only have that dialogue with our peers and the public, but that we might even be compensated for our creative efforts, which is another kind of validation. We’re not talking rich and famous; making a life with one’s work is enough.

But notice that in David’s description, even the monetary motivation has two dimensions: enabling consumption and validation.