Human Population Through Time—American Museum of Natural History

h/t Joseph Kimball

Daily Sugar-Sweetened Soft Drink Consumption Correlates with Liver Disease →

For more on the dangers of sugar, see “Miles Kimball on Diet and Health: A Reader's Guide.”

The Candification of Fruit—Bee Wilson

Fruit has a very positive reputation. But the story about fruit is actually more complicated. The other things in fruit are good, but the sugar in fruit is bad. Sugar doesn’t magically become innocent by being inside of fruit, though if there is enough fiber in a piece of fruit, that might slow down the absorption of the sugar somewhat.

In her Wall Street Journal article “Is Fruit Getting Sweeter?” Bee Wilson writes:

Is modern fruit bred to be sweeter than in the past? The short answer is yes …. Some of the most powerful evidence that fruit is sweeter than before comes from zoos. In 2018, it was reported that Melbourne Zoo in Australia had stopped giving fruit to most of its animals because cultivated fruit was now so sweet that it was causing tooth decay and weight gain. The monkeys at the zoo were weaned off bananas onto a lower-sugar vegetable-based diet.

Among fruit breeders, the word ‘quality’ is now routinely used as a synonym for ‘high in sugar’ (though firmness, color and size are also considerations)…. ‘in general, the sugar content’ of many fruits are now higher than before ‘owing to continuous selection and breeding.’ …

… the real problem with modern fruit is that it has become yet another sweet thing in a world awash with sugar. Even grapefruits, which used to be bracingly bitter, are sometimes now as sweet as oranges.

Thus, fruit is being bred to be less and less healthy. I hope this can be reversed. For those people who realize how unhealthy sugar is, it is possible to breed fruit that is tasty in other ways. This is something I predict people will become more and more interested in in the future.

Related Posts:

Best Health Guide: 10 Surprising Changes When You Quit Sugar

Heidi Turner, Michael Schwartz and Kristen Domonell on How Bad Sugar Is

Michael Lowe and Heidi Mitchell: Is Getting ‘Hangry’ Actually a Thing?

The Better Side of Conventional Wisdom about Diet and Health

How Many Thousands of Americans Will the Sugar Lobby's Latest Victory Kill?

Aseem Malhotra: Avoiding Sugar is Much More Powerful Than Taking Statins (link post)

Sam Apple on the Tragedy of Pro-Sugar Policies of the US Government

National Intervention Evidence for the Benefits of Reducing Sodium Intake

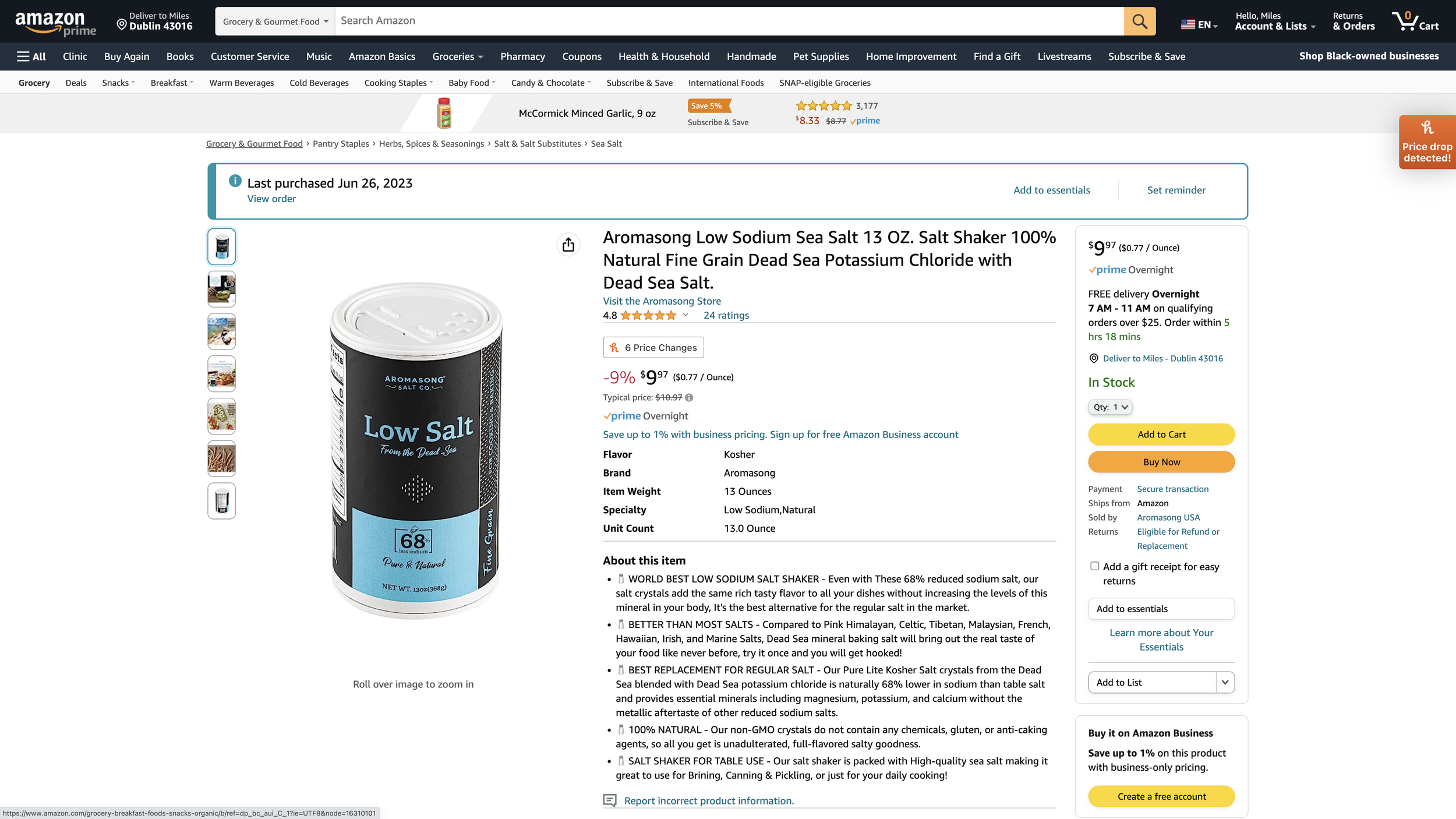

Bee Wilson’s June 22, 2023 Wall Street Journal article “It’s Too Bad Salt Tastes So Good” provided the most persuasive evidence I have seen for reducing sodium being beneficial for most people.

I find the national intervention evidence from the UK and Japan quite convincing about the benefits of reducing sodium intake for the average person. However, as the quotation in the third tweet notes, in the US and UK, most of our sodium intake is in highly processed food. (In Japan, traditional food has a lot of salt in it.) So those who avoid—as they should—highly processed food, may not need to reduce their sodium intake. I am in that category. I also test out as having low blood pressure. But if I ever start worrying about my sodium intake, I have bought some “Dead Sea Salt” that is 2/3 potassium chloride and only 1/3 Sodium Chloride, following Bee Wilson’s advice to try replacing some of one’s sodium chloride consumption with potassium chloride consumption.

Cyclic Sighing

I did a series of 4 blog posts on James Nestor’s book Breath a while back:

So, I was interested to see Jenny Taitz’s June 29, 2023 Wall Street Journal article “The Positive Power of a Good Sigh” on that topic. It describes “cyclic sighing”:

In a study published in January in the journal Cell Reports Medicine, Huberman and colleagues examined a technique known as “cyclic sighing.” To produce a sigh, people were instructed to close their lips and slowly inhale through the nose; then take a second inhale, completely filling the lungs; and then release an extended exhale from the mouth. Cyclic sighing involves gently repeating this sigh continuously for five minutes. The researchers found that people who practiced cyclic sighing every day for a month experienced reduced anxiety and increased positive emotions, with better results than other relaxation techniques such as mindful meditation.

Here, I think experimenting for yourself what effect it has is the best way to proceed. Here is a way Jenny Taitz suggests to think of cyclic sighing theoretically:

Intentionally heaving a physiological sigh in one way to recalibrate from breathing too much or holding our breath, as we do when we’re anxious.

A Massive Study Correlating Cannabis Use with Clinical Depression and Bipolar Disorder Illustrates Why Longitudinal Studies Aren't a Silver Bullet for Establishing Causality

The key passages from Susan Pinker’s July 6, 2023 Wall Street Journal article, “Cannabis Is Linked to Mental Illness” are:

Now a new longitudinal study has examined the medical records of all citizens of Denmark over the age of 16, some 6.5 million people in all, for patterns of diagnosis, hospitalization and treatment for substance use between 1995 and 2021. In the paper, published in the journal JAMA Psychiatry in May, Dr. Oskar Hougaard Jefsen of Aarhus University and colleagues showed that people who had previously been diagnosed with cannabis use disorder were almost twice as likely to be diagnosed later with clinical depression.

and

Though the association was strong, the authors note that they can’t say for certain whether chronic and heavy cannabis use induces psychosis, or whether people prone to mental illness are more likely to be heavy users. It makes sense that people who feel the symptoms of incapacitating depression or mania, or who sense apparitions or voices only they can hear, might try to self-medicate with cannabis.

Having a psychiatric disorder diagnosed after someone is determined to be addicted to marijuana doesn’t mean the marijuana use caused it. The beginnings of the psychiatric disorder were likely there before the diagnosis of it, and those beginnings could have made marijuana quite attractive as self-medication. I also wonder if people who are connected enough to the mental health system to get an addiction diagnosis aren’t more likely to get diagnosed for psychiatric disorders they have.

How then, can we establish causality? In her article, Susan Pinker writes:

Without a randomized controlled trial, which would be unethical in the extreme, it’s hard to untangle these strands definitively.

I don’t think that is quite true. First of all, a randomized controlled trial wouldn’t be unethical if the intervention was something that lowered marijuana use rather than raised it. One simply needs to get a brilliant idea of how to get a randomly chosen half of one’s sample to reduce their marijuana use.

Also, in this case, different states legalizing marijuana at different times provides a reasonably good natural experiment for differences-in-differences estimation that assumes the trend lines in each state for depression and bipolar disorder would have had an unchanging slope if it weren’t for marijuana legalization at different dates. Which states legalize isn’t random, but the known dates of legalization can help identify whether marijuana legalization had an effect on those mental health trends.

Further Reading: “An Example of Needing to Worry about Reverse Causality: Satisfaction with Aging and Objective Aging Outcomes” addresses a similar issue of reverse causality in a longitudinal study (that shows what happens to someone over time).

Sonia Sotomayor's Dissent in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard and the University of North Carolina Evinces an Impoverished View Of Our Ability to Measure Higher Education Outcomes

To me, the following from pages 51 and 52 of Sonia Sotomayor’s dissent in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard does not give enough credit to the potential of good social science (footnote omitted):

2

As noted above, this Court suggests that the use of race in college admissions is unworkable because respondents’ objectives are not sufficiently “measurable,” “focused,” “concrete,” and “coherent.” Ante, at 23, 26, 39. How much more precision is required or how universities are supposed to meet the Court’s measurability requirement, the Court’s opinion does not say. That is exactly the point. The Court is not interested in crafting a workable framework that promotes racial diversity on college campuses. Instead, it an- nounces a requirement designed to ensure all race-conscious plans fail. Any increased level of precision runs the risk of violating the Court’s admonition that colleges and universities operate their race-conscious admissions policies with no “‘specified percentage[s]’” and no “specific number[s] firmly in mind.” Grutter, 539 U. S., at 324, 335. Thus, the majority’s holding puts schools in an untenable position. It creates a legal framework where race-conscious plans must be measured with precision but also must not be measured with precision. That holding is not meant to infuse clarity into the strict scrutiny framework; it is designed to render strict scrutiny “ ‘fatal in fact.’ ” Id., at 326 (quoting Adarand Constructors, Inc., 515 U. S., at 237). Indeed, the Court gives the game away when it holds that, to the extent respondents are actually measuring their diversity objectives with any level of specificity (for example, with a “focus on numbers” or specific “numerical commitment”), their plans are unconstitutional. Ante, at 30–31; see also ante, at 29 (THOMAS, J., concurring) (“I highly doubt any [university] will be able to” show a “measurable state interest”).

Colleges and universities could do a lot to carefully measure in a times series educational outcomes of all kinds (included those claimed as benefits of race-conscious admissions) if they made it a priority. I have written on that theme before:

In “How to Foster Transformative Innovation in Higher Education,” I write:

I doubt that higher education in the United States will reform itself without a push from the outside. We need more competition from new kinds of higher education. The key to allowing alternative forms of higher education to flourish is to replace the current emphasis on accreditation, which tends to lock in the status quo, and instead have the government or a foundation with an interest in higher education develop high-quality assessment tools for what skills a student has at graduation. Distinct skills should be separately certified. The biggest emphasis should be on skills directly valuable in the labor market: writing, reading carefully, coding, the lesser computer and math skills needed to be a whiz with a spreadsheet, etc. But students should be able to get certified in every key skill that a college or university purports to teach. (Where what should be taught is disputed, as in the Humanities, there should be alternative certification routes, such as a certification in the use of Postmodernism and a separate certification for knowledge of what was conceived as the traditional canon 75 years ago. The nature of the assessment in each can be controlled by professors who believe in that particular school of thought.)

Whatever outcome is claimed for education at a particular college or from a particular course of study can be measured—typically by appropriate survey or quiz questions, sometimes by other types of data collection. There are many other outcomes of interest beyond bare racial statistics.

The Rise and Fall of the Mail-Order Home—Brian Potter →

The rise and fall of the mail-order home is important to know about because technological progress in home construction would probably be much greater if homes were largely made in factories. Don’t miss my post “Why Housing is So Expensive.”

Some Thoughts on Biden v. Nebraska

result from giving the prompt “impressionist painting for Supreme Court decision Biden versus Nebraska” to Stable Diffusion

Several recent US Supreme Court decisions have been interesting enough that I have read the full set of opinions for them. Biden v. Nebraska is one of them. I especially liked Amy Coney Barrett’s discussion of the “major questions doctrine” as simply a contextual interpretive principle rather than as a “substantive canon,” which she defines this way: “Substantive canons are rules of construction that advance values external to a statute.” Amy Coney Barrett is not comfortable with substantive canons, writing (with citations, footnotes, internal quotation marks and internal brackets omitted):

While many strong-form canons have a long historical pedigree, they are in significant tension with textualism insofar as they instruct a court to adopt something other than the statute’s most natural meaning. The usual textualist enterprise involves hearing the words as they would sound in the mind of a skilled, objectively reasonable user of words. But a strong-form canon loads the dice for or against a particular result in order to serve a value that the judiciary has chosen to specially protect. Even if the judiciary’s adoption of such canons can be reconciled with the Constitution, it is undeniable that they pose a lot of trouble for the honest textualist.

So what is the major questions doctrine if not a substantive canon? After discussing examples of statutory interpretation, Amy Coney Barrett writes:

Why is any of this relevant to the major questions doctrine? Because context is also relevant to interpreting the scope of a delegation. Think about agency law, which is all about delegations.

Intriguingly, Amy Coney Barrett rejects the idea that the major questions doctrine reflects bedrock “non-delegation principle” constitutional limits, saying instead it merely an interpretive principle given constitutional context:

Crucially, treating the Constitution’s structure as part of the context in which a delegation occurs is not the same as using a clear-statement rule to overenforce Article I’s non-delegation principle (which, again, is the rationale behind the substantive-canon view of the major questions doctrine). My point is simply that in a system of separated powers, a reasonably informed interpreter would expect Congress to legislate on “important subjects” while delegating away only “the details.” Wayman v. Southard, 10 Wheat. 1, 43 (1825). That is different from a normative rule that discourages Congress from empowering agencies. To see what I mean, return to the ambitious babysitter. Our expectation of clearer authorization for the amusement- park trip is not about discouraging the parent from giving significant leeway to the babysitter or forcing the parent to think hard before doing so. Instead, it reflects the intuition that the parent is in charge and sets the terms for the babysitter—so if a judgment is significant, we expect the parent to make it. If, by contrast, one parent left the children with the other parent for the weekend, we would view the same trip differently because the parents share authority over the children. In short, the balance of power between those in a relationship inevitably frames our understanding of their communications. And when it comes to the Nation’s policy, the Constitution gives Congress the reins—a point of context that no reasonable interpreter could ignore.

Thinking in terms of these issues of interpretation, I think that cancelling $10,000 of debt per person as the pandemic was coming to a close was beyond what Congress authorized, but the pause in payments during the pandemic was in line with what Congress authorized in an emergency. I hope that the Supreme Court decides as much if the pause in payments is litigated. We are sorely in need of an indication from the Supreme Court of how far the limitation on federal agency powers goes. Having the Supreme Court say the pause in payments was within the scope of the delegated powers but cancelling $10,000 of debt person as the pandemic was coming to a close would begin to reduce legal uncertainty about the major questions doctrine—legal uncertainty which at this point is severe.

Of course, in that interpretation, it is hard for me to be totally uninfluenced by my view, along with the majority of Americans, that the student debt forgiveness plan of the Biden administration was unfair. (See “Is Student Debt Forgiveness Fair.”)

In the dissent, what I found most persuasive was the argument that the litigants did not have standing to sue. The directly injured party, as determined by the Supreme Court majority, was MOHELA, which was a nonprofit government corporation in Missouri. Those in charge of MOHELA did not want to take any part in this litigation.

Although the US Constitution does limit the scope of courts to actual cases and controversies, the details of “standing” rules are really rules that the Supreme Court imposes on itself and on lower courts. Over the long haul, the Supreme Court has the right expertise to decide on what standing rules it should have. It can overrule precedent on standing rules if it so chooses.

That said, saying that an injury to MOHELA was an injury to Missouri seemed like a fig leaf to me: the Supreme Court majority knew that there was a crucial delegation of powers issue to be addressed and were determined to make a finding of standing so that they could address it. I agree with their determination to make a finding of standing somehow, but not with the fig leaf.

A more honest approach, which might be totally without precedent, or even against precedent, would be to argue that a major violation of the US Constitutional structure was an injury to states of the union that ratified the US Constitution or in their inception lose powers to the federal government on the expectation that constitutional rules will be followed.

To me, states of the union seem like the right entities to endow with standing to raise major constitutional questions. Someone should have standing to question the constitutionality of major Executive Branch actions. (It is not always possible to get a resolution by an entire house of Congress to raise such questions.) To make it easier for the Supreme Court to take this approach, let me propose a constitutional amendment giving states of the union standing to raise “major” constitutional questions. In the course of the adoption of such an amendment, the connection to the early-21st-century “major questions doctrine” should be made clear to aid in interpretation. However, it should also be made clear that major constitutional questions should include issues that do not involve the administrative state.

The evolution of the major questions doctrine is something I follow very closely because I am worried that some directions it could take might clip the wings of the Fed in a way that would land us in either hyperinflation or in a repeat of the Great Recession. I believe that Congress knowingly delegated enormous powers to the Fed, believing that it is good to have an independent central bank (though this belief was not always expressed as valuing “central bank independence”). Appropriate and inappropriate criticisms of Fed actions by members of Congress should not obscure the legitimacy of that delegation.

Actually, I am much less worried about the Fed ever actually losing a case about core monetary policy actions than about a repeat of the Great Recession from the Fed imposing limits on itself, out of legal uncertainty about what they are allowed to do. The more quickly the Supreme Court can reduce legal uncertainty about the scope of agency powers in the new era of the “major questions doctrine,” the better.

For the Fed, the key question is whether an agency can use tools clearly granted it by Congress to do something in pursuance of the mandate given it by Congress in a way that is dramatically new and unprecedented, called for by either a new kind of emergency or by the advance of economic science in relation to monetary policy. It would be a bad idea for the Supreme Court to make novelty itself suspect. The Fed has been doing gigantic things for over a century—a century that encompassed great advances in macroeconomics, and therefore dramatic changes in how the Fed does its job. Should all progress in monetary policy from here on be stopped during periods of a divided or deadlocked Legislative Branch? Or can old tools Congress has clearly authorized be used in dramatically new ways to accomplish Congress’s order to set the economy to rights as much as possible with those tools?