Charles Lane on Thomas Piketty and Henry George

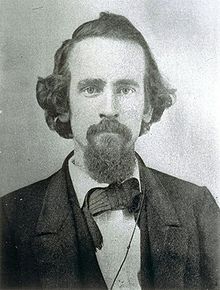

Link to Wikipedia article on Henry George

Charles Lane compares Thomas Piketty to Henry George in hi May 15, 2014 Washington Post op-ed,

Thomas Piketty identifies an important ill of capitalism but not its cure.

Charles gives a succinct evaluation of both Thomas’s and Henry’s proposals:

Alas, Piketty’s global wealth tax and George’s single tax suffer from the same defect, and it’s not political impracticality — after all, George nearly got himself elected mayor of New York City in 1886.

It’s the inherent difficulty of separating the productive, untaxed component of the return on land or capital from the unproductive, taxed part. …

As a result, it’s hard to devise a tax on wealth that raises a significant amount of revenue but doesn’t discourage at least some socially beneficial saving or entrepreneurship. The potential for adverse unintended consequences — economic and political — is greater than Piketty seems to realize.

Quite distinct from this concern about incentives, Charles goes on to a positive note about having power in the hands of private individuals:

Great private fortunes can indeed entitle their owners to an undue share of society’s current income and political power. At times, however, private wealth can serve as a font of charity or, indeed, a bulwark against government overreach.

These are indeed the key issues to think about in relation to wealth taxation.

I have always liked Henry George’s proposal, and pointed out how a carbon tax can be seen as akin to Henry George’s single tax in my post “‘Henry George and the Carbon Tax’: A Quick Response to Noah Smith.” And I like Noah’s application of Henry George’s idea to San Francisco. But Thomas Piketty himself points to the difficulty of getting enough revenue from taxing the value of unimproved land alone:

In particular, it seems impossible to compare in any precise way the value of pure land long ago with its value today. The principal issue today is urban land: farmland is worth less than 10 percent of national income in both France and Britain. But it is no easier to measure the value of pure urban land today, independent not only of buildings and construction but also of infrastructure and other improvements needed to make the land attractive, than to measure the value of pure farmland in the eighteenth century. According to my estimates, the annual flow of investment over the past few decades can account for almost all the value of wealth, including wealth in real estate, in 2010. …

… the fact that total capital, especially in real estate, in the rich countries can be explained fairly well in terms of the accumulation of flows of saving and investment obviously does not preclude the existence of large local capital gains linked to the concentration of population in particular areas, such as major capitals. It would not make much sense to explain the increase in the value of buildings on the Champs-Elysées or, for that matter, anywhere in Paris exclusively in terms of investment flows. Our estimates suggest, however, that these large capital gains on real estate in certain areas were largely compensated by capital losses in other areas, which became less attractive, such as smaller cities or decaying neighborhoods. (Capital in the Twenty-First Century, p. 197.)

Thomas Piketty’s example of the unearned rise in the value of one’s urban land may seem like an opening for non-distortionary taxation, but in fact from the standpoint of efficiency these positive externalities suggest subsidizing all activities that create these positive externalities for land values, of which just as many are private activities as are activities of the government. (And many activities of the government do not raise land values.) Also, I worry that urban governments often make land prices for certain favored plots go up while reducing the total value of land (and social welfare) by putting tight restrictions on building. This is a concern that Matthew Yglesias raises in his book The Rent Is Too Damn High: What To Do About It, And Why It Matters More Than You Think.