Flexible Dogmatism: The Mormon Position on Infallibility

For Mormon Church watchers, it was big news when (without any other announcement) the official website of the Mormon Church posted on December 6, 2013 a new article on “Race and the Priesthood.” The subject of the article was this fact:

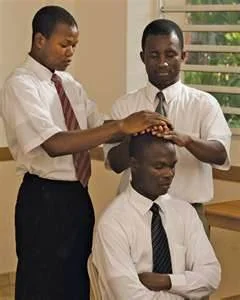

… for much of its history—from the mid-1800s until 1978—the Church did not ordain men of black African descent to its priesthood or allow black men or women to participate in temple endowment or sealing ordinances.

The article is remarkable in forthrightly rejecting the racist theories that Mormons had given historically for this policy. As part of the argument against racist theologies as an explanation, the article points to the fact that the Mormon Church ordained men of African descent during the lifetime of its founder, Joseph Smith. Then the ban on people of African descent being allowed to receive the priesthood is presented as an unexplained action of Joseph Smith’s successor, Brigham Young:

During the first two decades of the Church’s existence, a few black men were ordained to the priesthood. One of these men, Elijah Abel, also participated in temple ceremonies in Kirtland, Ohio, and was later baptized as proxy for deceased relatives in Nauvoo, Illinois. There is no evidence that any black men were denied the priesthood during Joseph Smith’s lifetime.

In 1852, President Brigham Young publicly announced that men of black African descent could no longer be ordained to the priesthood, though thereafter blacks continued to join the Church through baptism and receiving the gift of the Holy Ghost. Following the death of Brigham Young, subsequent Church presidents restricted blacks from receiving the temple endowment or being married in the temple. Over time, Church leaders and members advanced many theories to explain the priesthood and temple restrictions. None of these explanations is accepted today as the official doctrine of the Church.

The article does not give examples, but two prominent theories were

- God was thought to have punished Cain by denying his descendants the priesthood, and people of African descent were believed to be descendants of Cain.

- Before joining their bodies at birth, the spirits of those of African descent were said to have been less strong supporters of Jesus in the “War in Heaven” between Jesus and Satan. (See the last quotation in my post “The Mormon View of Jesus” for some of the background on the primordial dispute between Jesus and Satan)

Although there is no text of a divine revelation recorded for Brigham Young’s policy of denying people of African descent the Mormon priesthood, Mormon Church leaders believed that a divine revelation was necessary to overturn this policy:

Nevertheless, [in the 1950’s,] given the long history of withholding the priesthood from men of black African descent, Church leaders believed that a revelation from God was needed to alter the policy, and they made ongoing efforts to understand what should be done.

Among the Mormon Church leaders who believed a divine revelation was necessary to change the policy of denying people of African descent the priesthood was my grandfather, Spencer W. Kimball. Consequently, as President of the Church, he sought such a divine revelation. The article “Race and the Priesthood” cites my father Edward L. Kimball's BYU Studies article “Spencer W. Kimball and the Revelation on Priesthood” for a detailed account of my grandfather’s spiritual experience and the spiritual experiences to which he led his colleagues–spiritual experiences which led to the adoption of the Mormon Church’s “Official Declaration 2,” which erases all official racial barriers in Mormonism. (“Official Declaration 1” was the beginning of the renunciation of polygamy.)

Today, the Church disavows the theories advanced in the past that black skin is a sign of divine disfavor or curse, or that it reflects actions in a premortal life; that mixed-race marriages are a sin; or that blacks or people of any other race or ethnicity are inferior in any way to anyone else. Church leaders today unequivocally condemn all racism, past and present, in any form.23

In addition to the renunciation of racist explanations for the pre-1978 ban on people of African descent holding the priesthood, the article “Race and the Priesthood.” is interesting in what it says about the fallibility of Mormon Church leaders. The doctrine of continuing revelation that is so central to Mormonism always implied that church leaders can be wrong about theology. In that spirit,

Soon after the revelation [in 1978] Elder Bruce R. McConkie, an apostle, spoke of new “light and knowledge” that had erased previously “limited understanding.”22

It is also clear that Mormon Church leaders can change previous policies. But the Church leadership is essentially held to be infallible in major decisions about what the Church should do at a given moment in time. That doctrine was necessary when the Mormon Church turned away from polygamy, to the dismay of many members. “Official Declaration 1” as it appears in Mormon scriptures includes this statement by Mormon Church President Wilford Woodruff:

The Lord will never permit me or any other man who stands as President of this Church to lead you astray. It is not in the programme. It is not in the mind of God. If I were to attempt that, the Lord would remove me out of my place, and so He will any other man who attempts to lead the children of men astray from the oracles of God and from their duty.

According to these principles, the Mormon Church can renounce past policies and can renounce past theologies, but it cannot renounce the rightness of past policies at the time they were in effect. This subtle position provides the institutional strength that comes from a doctrine of infallibility without the rigidity that would result from a less subtle version of an infallibility doctrine.

In my reading, the article “Race and the Priesthood” is very careful to avoid saying that Brigham Young made a mistake in denying men of African descent the priesthood–unless the condemnation of “racism, past and present, in any form” is intended as a condemnation of that policy. But I think that wording is intended to be ambiguous and deniable; for example, if God thought the pre-1978 ban was wise for some inscrutable reason, that would not be racism, since God, being perfect, cannot be racist. A possible objective would be to have the words seem to condemn the policy to those who think the policy was racist, but not to seem to condemn it to those who think Church leaders could not make such a big mistake.

In the 1990’s one of my friends coined the wonderful phrase “flexible dogmatism” to describe the Mormon position on infallibility. The one key difference between flexible dogmatism then and flexible dogmatism now is that the rise of the internet has reduced the extent to which the Mormon Church can pretend beyond historical fact that its current policies held in the past as well. I am impressed by how gracefully the article “Race and the Priesthood” deals with the inability to dissemble in that way, while maintaining the essence of flexible dogmatism.

As part of what makes flexible dogmatism work, my friend points to “rolling interpretations” of authoritative statements that provide the "authority of the past to the changing present.“ (For example, when Brigham Young said that some day men of African descent would enjoy the blessings of the priesthood, he may have meant they would receive the priesthood in the afterlife. This statement was later interpreted as a foreshadowing the extension of the priesthood to men of African descent in 1978.)

At the grassroots level, the Mormon version of infallibility is well expressed by the children’s song with these lyrics:

Follow the prophet, follow the prophet,

Follow the prophet; don’t go astray.

Follow the prophet, follow the prophet,

Follow the prophet; he knows the way.

The power of this song is hard to appreciate without hearing the tune, which has always sounded to me like a tune for the kind of Russian dance pictured below: