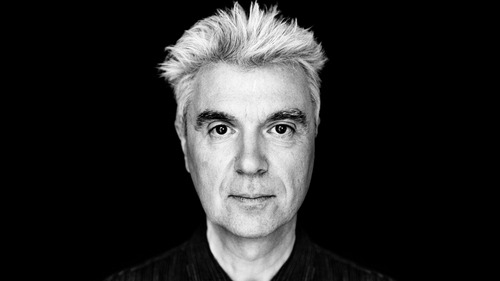

David Byrne: De Gustibus Non Est Disputandum

Economists use the Latin adage “De gustibus, non est disputandum”–“There is no disputing of tastes”–to express the idea that in assessing an individual’s welfare, economists should use that individual’s preferences, not their own. This doctrine of deference to the desires, likes and dislikes of those who are affected by a policy is also evident in the praise economists usually intend when they use the word “non-paternalistic." What this doctrine means in practice is that when economists are acting in their capacity as policy advisors, their self-appointed task is to arrange things so that people get more of what they want, whatever it is that they want. (Of course, economists also often act in the capacity of scientists, with the strict task of finding out the truth and figuring out how the world works. Greg Mankiw highlights the two tasks of economists both in his Principles of Economics textbook in the title of his Journal of Economic Perspectives article "The Macroeconomist as Scientist and Engineer,”)

One of the areas where tastes are disputed is in the arts. David Byrne argues that even there, people’s tastes should be respected. in Chapter 9 of his book How Music Works he takes apart the view that the consumption of some types of art and music is superior to the consumption of other types:

Is some music really better than other music? Who decides? What effect does music have on us that might make it good or not-so-good? …

… it is presumed that certain kinds of music have more beneficial effects than others. Some music can make you a “better” person, and by extension other kinds of music might even be detrimental (and they don’t mean it will damage your eardrums)–certainly it won’t be as morally uplifting. The assumption is that upon hearing “good” music, you will somehow become a more morally grounded person. How does that work?

The background of those defining what is good or bad goes a long way toward explaining this attitude. The use of music to make a connection between a love of high art and economic success and status isn’t always subtle. Canadian writer Colin Eatock points out that classical music has been piped into 7-Elevens, the London Underground, and the Toronto subways, and the result has been a decrease in robberies, assaults, and vandalism. Wow–powerful stuff. Music can alter behavior after all! This statistic is held up as proof that some music does indeed have magical, morally uplifting properties. What a marketing opportunity! But another view holds that this tactic is a way of making certain people feel unwelcome. They know it’s not “their” music, and they sense that the message is, as Eatock says, “Move along, this is not your cultural space.” Others have referred to this as “musical bug spray.” It’s a way of using music to create and manage social space.

The economist John Maynard Keynes even claimed that many kinds of amateur and popular music do in fact reduce one’s moral standing. In general, we are indoctrinated to believe that classical music, and maybe some kinds of jazz, possess a kind of moral medicine–whereas hip-hop, club music, and certainly heavy metal lack anything like a positive moral essence. It all sounds slightly ridiculous when i spell it out like this, but such presumptions continue to inform many decisions regarding the arts and the way they’re supported.

John Carey, an English literary critic who writes for The Sunday Times, wrote a wonderful book called What Good are the Arts that illustrates how officiallly sanctioned art and music gets privileged. Carey cites the philosopher Immanuel Kant: “Now I say the beautiful is the symbol of the morally good, and that it is only in this respect that it gives pleasure…The mind is made conscious of a certain ennoblement and elevation above the mere sensibility to pleasure.” So, according to Kant, the reason we find a given work of art beautiful is because we sense–but how do we sense this, I wonder? that some innate, benevolent, moral essence is tucked in there, elevating us, and we like that. In this view, pleasure and more uplift are linked. Pleasure alone, without this beautiful entanglement, is not a good thing–but packaged with moral uplift, pleasure is, well, excusable. That might sound pretty mystical and a bit silly, especially if you concede that standards of beauty just might be relative. In Kant’s Protestant world, all forms of sensuality inevitably lead to loose morals and eternal damnation. Pleasures needs a moral note to be acceptable.

When Goethe visited the Dresden Gallery, he noted the “emotion experienced up entering a House of God.” He was referring to the positive and uplifting emotions, not fear and trembling at the prospect of encountering the Old Testament God. William Hazlitt, the brilliant nineteenth-centuray essayist, said that going to the National Gallery on Pall Mall was like making a pilgrimage to the “holy of holies… [an] act of devotion performed at the shrine of art.” Once again it would appear that this God of Art is a benevolent one who will not strike young William down with a bolt of lightning for an occasional aesthetic sin. If such a punishment sounds like an exaggeration, keep in mind that not too long before Hazlitt’s time, one could indeed be burned at the stake for small blasphemies. And if the appreciation of the finer realms of art and music is akin to praying at a shrine, then one must accept that artistic blasphemy also has its consequences.

A corollary to the idea that high art is good for you is that it can be prescribed like medicine. Like a kind of inoculation, it can arrest, and possibly even begin to reverse, our baser tendencies. The Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote that the poor needed art “to purify their tastes and wean them from [their] polluting and debasing habits.” Charles Kingsley, a nineteenth-century English novelist, was even more explicit: “Pictures raise blessed thoughts in me–why not in you, my brother? Believe it, toil-worn worker, in spite of thy foul alley, they crowded lodging, thy thin, pale wife, believe it, thou too, and thine will some day have your share of beauty.” Galleries like Whitechapel in London were opened in working-class neighborhoods so that the downtrodden might have a taste of the finer things in life. Having done a little bit of manual labor myself, I can attest that sometimes beer, music, or TV might be all one is ready for after a long day of physically demanding work.

Across the ocean, the titans of American industry continued this trend. They founded the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1872, filling it with works drawn from their massive European art collections in the hope that the place would act as a unifying force for an increasingly diverse citizenry–a matter of some urgency, given the massive number of immigrants who were joining the nation. One of the Met’s founders, Joseph Hodges Chosate, wrote, “Knowledge of art in its higher forms of beauty would tend directly to humanize, to educate and to refine a practical and laborious people.

The late Thomas Hoving, who ran the Met in the sixties and seventies, and his rival J. Carter Brown, who headed the National Gallery in Washington DC, both felt that democratizing art meant getting everyone to like the things that they liked. It meant letting everyone know that here, in their museums, was the good stuff, the important stuff, the stuff with that mystical aura. [The book illustrates] a promotion the Met did in the sixties in LIFE magazine. The idea was that even reduced to the size of a postcard, reproductions of verified masterpieces could still enlighten the American masses. And so cheap!